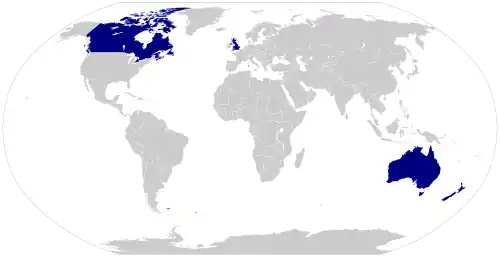

CANZUK

CANZUK is a proposed alliance comprising Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom as part of an international organisation or confederation similar in scope to the former European Economic Community.[1] This includes increased trade, foreign policy co-operation, military co-operation and mobility of citizens between the four states, tied together by similar economic systems, social values and political and legal systems, in addition to the majority population of each country speaking English.[2] The idea is lobbied by the advocacy group CANZUK International[3] and supported primarily by conservatives.[4][5] Other supporters include think tanks such as the Adam Smith Institute,[6] the Henry Jackson Society,[7] Bruges Group[8] and politicians from the four countries.

History

The term

The term CANZUK was first coined by William David McIntyre in his 1967 book Colonies into Commonwealth in the context of a "CANZUK Union".[9] The idea of increased migration, trade and foreign policy cooperation between the CANZUK countries was created and popularized in 2015 by CEO and Founder of CANZUK International[10] (formerly the Commonwealth Freedom of Movement Organisation), James Skinner.[11][12]

In the wake of the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum and the decision made by the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, writers such as Andrew Lilico and James C. Bennett, along with academics such as the historian Andrew Roberts, also advocated that Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom merge and form a new entity in international politics.[13][14] Andrew Roberts suggested that such a bloc could slot into the international order as a third pillar of the West (alongside the United States and the European Union). Beyond this, Roberts argues that due to its territorial scale, geographic scope and advanced economy that it would qualify as a "great power" and potentially a "global power" (or emerging superpower).[15]

Some advocates such as Roberts favour a federal or confederal union. Others, such as Lilico, describe the objective as being the creation of a "geopolitical partnership" akin to the European Economic Community.[16] In the version favoured by Lilico, by the advocacy group CANZUK international and by the Conservative Party of Canada, the proposal would involve the creation of a free-movement zone, a multilateral free trade agreement and a security partnership. The more general concept of deepening trade ties (with or without a multilateral agreement) has many advocates, including figures such as former Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison,[17] Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau,[18] former British Prime Minister Theresa May[19] and former New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern.[20]

Relationship

Canada, Australia and New Zealand are former settler colonies of the British Empire where people of British ethnic origin came to constitute the majority of the population.[21] Today, the four CANZUK countries maintain a close affinity of cultural, diplomatic and military ties to one another. The Australian and New Zealand flags contain the flag of the United Kingdom in their canton; and the Union Flag is also one of two official flags of Canada (referred to as the Royal Union Flag).

Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom are also Commonwealth realms which share Charles III as their constitutional monarch and their head of state. The countries share a number of institutional, linguistic and religious similarities such as the use of political systems based upon the Westminster parliamentary system of government, and common law. The CANZUK countries form part of the English-speaking world and share a number of Anglosphere military initiatives with each other including the Fincastle Trophy, Five Eyes intelligence, ABCANZ Armies and AUSCANNZUKUS, which are concerned with increased military and naval co-operation. Canada and the United Kingdom are allied through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization while Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom are allied through the Five Power Defence Arrangements.

All four nations have diverse, multicultural populations, free and open presses, and are closely aligned on key social issues. Public relations are extremely warm between the four countries, with consistent evidence that people in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom regard each other's countries as their country's closest friends and allies in the world.

Since 1983, Australia and New Zealand have had formal trade ties with the Closer Economic Relations (CER) agreement.

In 2021 Australia and the United Kingdom agreed to one of the broadest trade agreements in Australia's history, only comparable with a similar deal between New Zealand and Australia. Greatly liberalising free movement of goods and people, the new agreement will reduce technological and digital barriers between the two nations. It is intended that lawyer degrees in Australia and the United Kingdom will have the same legal framework, making it easier for lawyers in both nations to apply for work in each other's countries. The new agreement will reduce visa requirements for unskilled farmworkers and other regional work sectors.[22]

Country comparison

Economic comparison

Using data from 2019, below is a table comparing the CANZUK countries to each other, as well as their combined size as a percentage of the world.

| Country | Population | Area | Exclusive

Economic Zone (2017)[31] |

Military Expenditures (USD billion - 2020)[37] | Nominal GDP

(billions USD)[38] |

Nominal GDP per capita

(USD) |

PPP GDP

(billions USD)[39] |

PPP GDP per capita

(USD) |

National Wealth

(billions USD)[40] |

National Wealth

per capita (USD) |

Human Development

Index (2021)[41] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38,014,184[42] | 9,984,670 km2[23] | 5,559,077 km2 | 22.50 | $1,984 | $48,774 | $1,931 | $51,749 | $7,407 | $202,240 | 0.936 (very high) | |

| 25,741,500[43] | 7,741,220 km2[24] | 8,505,348 km2 | 26.30 | $1,500 | $61,359 | $1,235 | $50,522 | $7,329 | $299,748 | 0.951 (very high) | |

| 5,007,330[44] | 268,838 km2[25] | 4,420,565 km2 | 4.30 | $206 | $42,692 | $215 | $42,940 | $1,162 | $240,821 | 0.937 (very high) | |

| 67,886,004[45] | 243,610 km2[26] | 6,805,586 km2 | 55.10 | $3,124 | $44,367 | $2,880 | $43,520 | $14,073 | $212,640 | 0.929 (very high) | |

| Total | 136,649,018 | 18,238,338 km2 | 25,290,576 km2 | 108.2 | $6,621 | $48,765 | $6,261 | $45,919 | $29,971 | $226,913 | 0.938 (very high) |

| Total as % of World | 1.7% | 11.7%[46] | 18.3% | 5.4% | 7.4% | – | 4.8% | – | 10.7% | – | – |

Territories and dependencies

Canada

There are three territories in Canada. Unlike the provinces, the territories of Canada have no inherent sovereignty and have only those powers delegated to them by the federal government.[47][48][49] They include all of mainland Canada north of latitude 60° north and west of Hudson Bay and all islands north of the Canadian mainland (from those in James Bay to the Queen Elizabeth Islands). The following table lists the territories in order of precedence (each province has precedence over all the territories, regardless of the date each territory was created).

| Territory | Flag | Arms | Capital | Population[lower-alpha 5] | Area (km2)[50] | Official languages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northwest Territories |  |

Yellowknife | 44,982 | 1,346,106 | Chipewyan, Cree, English, French, Gwich'in, Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun, North Slavey, South Slavey, Tłįchǫ[51] | |

| Nunavut | .svg.png.webp) |

Iqaluit | 39,486 | 2,093,190 | Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, English, French[52] | |

| Yukon | .svg.png.webp) |

Whitehorse | 41,293 | 482,443 | English, French[53] |

Australia

In addition to the six Australian States, Australia also comprises ten territories, whose existence and governmental structure (if any) depend on federal legislation. The territories are distinguished for federal administrative purposes between internal territories, i.e. those within the Australian mainland, and external territories, although the differences among all the territories relate to population rather than location.

Two of the three internal territories—the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), which was established to be a neutral site of the federal capital, and the Northern Territory—function almost as states. Each has self-government, through its legislative assembly, but the assembly's legislation can be federally overridden. Each has its own judiciary, with appeal to a federal court. The third internal territory, the Jervis Bay Territory, is the product of Australia's complex relationship with its capital city; rather than having the same level of autonomy as the other internal territories, it has services provided by the ACT.

There are also seven external territories, not part of the Australian mainland or of any state. Three of them have a small permanent population, two have tiny and transient populations, and two are uninhabited. All are directly administered by the federal Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities (or the Department of the Environment and Energy in the case of the Australian Antarctic Territory). Norfolk Island, which is permanently populated, was partially self-governing until 2015.

| Territory | Flag | Coat of Arms | Capital (largest settlement) |

Population (Jun 2019)[54] |

Area (km2)[55] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal territories | |||||

| Australian Capital Territory |  |

Canberra | 426,709 | 2,358 | |

| Jervis Bay Territory |  |

None (Jervis Bay Village) | 405 | 67 | |

| Northern Territory |  |

Darwin | 245,869 | 1,419,630 | |

| External territories | |||||

| Ashmore and Cartier Islands |  |

None (offshore anchorage) | 0 | 750[56] | |

| Australian Antarctic Territory | None (Davis Station) | Less than 1,000 | 5,896,500 km | ||

| Christmas Island | Flying Fish Cove | 1,938 | 135 | ||

| Cocos (Keeling) Islands | West Island | 547 | 14 | ||

| Coral Sea Islands | None (Willis Island) | 4[lower-alpha 6] | 780,000 | ||

| Heard Island and McDonald Islands | None (Atlas Cove) | 0 | 372 | ||

| Norfolk Island |  |

Kingston | 1,758 | 35 | |

New Zealand

The Pacific islands of the Cook Islands and Niue became New Zealand's first colonies in 1901 and then protectorates. From 1965 the Cook Islands became self-governing, as did Niue from 1974. Tokelau came under New Zealand control in 1925 and remains a non-self-governing territory.[58]

The Ross Dependency comprises that sector of the Antarctic continent between 160° east and 150° west longitude, together with the islands lying between those degrees of longitude and south of latitude 60° south.[59] The British (imperial) government took possession of this territory in 1923 and entrusted it to the administration of New Zealand. Neither Russia nor the United States recognises this claim, and the matter remains unresolved (along with all other Antarctic claims) by the Antarctic Treaty, which serves to mostly smooth over these differences. The area is uninhabited, apart from scientific bases.

New Zealand citizenship law treats all parts of the Realm equally, so most people born in New Zealand, the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau and the Ross Dependency before 2006 are New Zealand citizens. Further conditions apply for those born from 2006 onwards.[60]

| Territory | Flag | Coat of Arms | Capital (largest settlement) |

Population

(Jun 2018)[54] |

Area (km2)[55] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associated states | |||||

| Cook Islands |  |

Avarua | 21,388 | 236 | |

| Niue |  |

Alofi | 1,145 | 260 | |

| Dependent territories | |||||

| Ross Dependency |  |

None (Scott Base) | Scott Base: 10–85

McMurdo Station: 200–1,000 (seasonally) |

450,000 | |

| Tokelau |  |

Fakaofo | 1,405 | 10 | |

British Overseas Territories

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs) are fourteen territories all with a constitutional link with – but not forming part of – the United Kingdom.[61][62] Most of the permanently inhabited territories are internally self-governing, with the UK retaining responsibility for defence and foreign relations. Three are inhabited only by a transitory population of military or scientific personnel. They all have the British monarch as head of state.[63]

The term "British Overseas Territory" was introduced by the British Overseas Territories Act 2002, replacing the term British Dependent Territory, introduced by the British Nationality Act 1981. Prior to 1 January 1983, the territories were officially referred to as British Crown Colonies.

The British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies are themselves distinct from the Commonwealth realms, a group of 15 independent countries (including the United Kingdom) each having Charles III as their reigning monarch, and from the Commonwealth of Nations, a voluntary association of 54 countries mostly with historic links to the British Empire (which also includes all Commonwealth realms).

As of April 2018, three Territories (the Falkland Islands, Gibraltar and the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia on Cyprus) are the responsibility of the Minister of State for Europe and the Americas; the Minister responsible for the remaining Territories is the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for the Overseas Territories and Sustainable Development.[64]

| Name | Flag | Arms | Capital | Population | Area | Location | GDP (nominal) | GDP Per Capita (nominal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anguilla |  |

The Valley | 14,869(2019 estimate)[65] | 91 km2 (35.1 sq mi)[66] | Caribbean, North Atlantic Ocean | £141.62 million | £9,850 | |

| Bermuda |  |

Hamilton | 62,506(2019 estimate)[67] | 54 km2 (20.8 sq mi)[68] | North Atlantic Ocean between the Azores, the Caribbean, Cape Sable Island and Canada | £4.5 billion | £69,240 | |

| British Antarctic Territory |  |

Rothera (main base) | 50 non-permanent in winter, over 400 in summer (research personnel)[69] | 1,709,400 km2 (660,000 sq mi)[66] | Antarctica | |||

| British Indian Ocean Territory |  |

Diego Garcia (base) | 3,000 non-permanent (UK and US military personnel; estimate)[70] | 60 km2 (23 sq mi)[71] | Indian Ocean | |||

| British Virgin Islands |  |

Road Town | 31,758 (2018 census) | 153 km2 (59 sq mi)[72] | Caribbean, North Atlantic Ocean | £870 million | £28,040 | |

| Cayman Islands |  |

George Town | 68,076 (2019 estimate)[73] | 264 km2 (101.9 sq mi)[73] | Caribbean | £4.15 billion | £146,250 | |

| Falkland Islands |  |

Stanley | 3,377 (2019 estimate)[74] 1,350 non-permanent (UK military personnel; 2012 estimate) | 12,173 km2 (4,700 sq mi)[68] | South Atlantic Ocean | £132.82 million | £57,170 | |

| Gibraltar | .svg.png.webp) |

Gibraltar | 33,701(2019 estimate)[75] 1,250 non-permanent (UK military personnel; 2012 estimate) | 6.5 km2 (2.5 sq mi)[76] | Iberian Peninsula, Continental Europe | £1.89 billion | £74,960 | |

| Montserrat |  |

Plymouth (abandoned – de facto capital Brades) | 5,215 (2019 census) | 101 km2 (39 sq mi)[77] | Caribbean, North Atlantic Ocean | £130.72 million | £25,060 | |

| Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands |  |

Adamstown | 50 (2018 estimate)[78] 6 non-permanent (2014 estimate)[79] | 47 km2 (18 sq mi)[80] | Pacific Ocean | £84,870 | £1,700 | |

| Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, including: |

|

Jamestown | 5,633 (total; 2016 census) | 420 km2 (162 sq mi) | South Atlantic Ocean | £18.65 million | £4,570 | |

| Saint Helena | 4,349 (Saint Helena; 2019 census)[81] | |||||||

| Ascension Island |  |

880 (Ascension; estimate)[82] 1,000 non-permanent UK military personnel (estimate)[82] | ||||||

| Tristan da Cunha |  |

300 (estimate)[82] 9 non-permanent (weather personnel) | ||||||

| South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands |  |

King Edward Point | 99 non-permanent (officials and research personnel)[83] | 3,903 km2 (1,507 sq mi)[84] | South Atlantic Ocean | |||

| Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia |  |

Episkopi Cantonment | 7,700 (Cypriots; estimate) 8,000 non-permanent (UK military personnel; estimate) | 255 km2 (98 sq mi)[85] | Cyprus, Mediterranean Sea | |||

| Turks and Caicos Islands |  |

Cockburn Town | 38,191 (2019 estimate)[86] | 430 km2 (166 sq mi)[87] | Lucayan Archipelago, North Atlantic Ocean | £830 million | £21,920 |

Crown Dependencies

The Crown Dependencies (French: Dépendances de la Couronne; Manx: Croghaneyn-crooin) are three island territories off the coast of Great Britain that are self-governing possessions of The Crown: the Bailiwick of Guernsey, the Bailiwick of Jersey and the Isle of Man. They do not form part of either the United Kingdom or the British Overseas Territories.[88][89] Internationally, the dependencies are considered "territories for which the United Kingdom is responsible", rather than sovereign states.[90] As a result, they are not member states of the Commonwealth of Nations.[91] However, they do have relationships with the Commonwealth, the European Union, and other international organisations, and are members of the British–Irish Council. They have their own teams in the Commonwealth Games.

As the Crown dependencies are not sovereign states, the power to pass legislation affecting the islands ultimately rests with the government of the United Kingdom (though this is rarely done without the consent of the dependencies, and the right to do so is disputed). However, they each have their own legislative assembly, with the power to legislate on many local matters with the assent of the Crown (Privy Council, or in the case of the Isle of Man in certain circumstances the Lieutenant-Governor).[92] In each case, the head of government is called the Chief Minister.

| Name | Flag | Coat of Arms | Capital | Population | Area | Title of Monarch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bailiwick of GuernseyA | Alderney |

|

Saint Anne | 65,849 | 78 km2 (30 sq mi) | Duke of Normandy |

Guernsey |

|

Saint Peter Port (capital of the whole Bailiwick and of Guernsey) | ||||

Sark |

|

The Seigneurie (de facto; Sark does not have a capital city) | ||||

| Bailiwick of Jersey |  |

Saint Helier | 106,800 | 118.2 km2 (46 sq mi) | ||

| Isle of Man |  |

Douglas | 84,997 | 572 km2 (221 sq mi) | Lord of Mann |

Supporting views

Several organisations have been set up that promote, to varying degrees, much closer associations between the CANZUK nations. CANZUK International has, as its stated aim, the desire to establish an area of freedom of movement akin to that which existed before the European Communities Act 1972, or as a mirror to the rights of free movement as seen within the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement.[93] Other organisations are largely voluntary groupings of those who advocate the more specific idea of transnational union, such as "CANZUK Uniting".[94]

Canada

Several members of parliament voiced their support for the CANZUK initiative during the Conservative Party of Canada's 2017 leadership election. The eventual winner of the leadership election, Andrew Scheer, stated his support for a CANZUK free trade deal in March 2017. At a debate in Vancouver, British Columbia, Scheer stated, "I very much support a trade deal with those countries. Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom have a similar basis of law, they have a common democratic system, they have the same types of legislation and regulations around investment and trade. Those are the types of things we don't enjoy with China".[95]

Other candidates for the Conservative Party leadership also adopted CANZUK free trade and free movement as a part of their campaigns platforms, including Erin O'Toole and Michael Chong.[96] In April 2017, O'Toole released a video with CANZUK International, describing the CANZUK initiative as "a no brainer", stating that Canada already offers free trade and free mobility with citizens of the United States and should therefore offer such benefits to "our other closest allies".[97] O'Toole again supported CANZUK during his successful campaign for the leadership of the Conservative Party of Canada in 2020.[98]

In August 2018, the Conservative Party of Canada adopted CANZUK as official party policy at their 2018 party convention by 215 votes to 7.[99][100] The party presently serves as the Official Opposition in the Parliament of Canada.

After his victory in the August 2020 Conservative Party of Canada leadership election, Erin O'Toole, made CANZUK a priority in his platform.[101][102]

Australia

In August 2017, Liberal Senator for Victoria, James Paterson, published an opinion-piece in the Australian Financial Review declaring support for CANZUK free trade and free movement, stating "With Australia, New Zealand and Canada all lining up to sign post-Brexit trade agreements with the United Kingdom, we have an opportunity to push for a wide-ranging agreement between all four Commonwealth nations...It's an idea whose time has come."[103]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, ACT New Zealand has expressed support for a "free-movement zone", with leader David Seymour stating, "Successful nations like Britain and New Zealand shouldn't be putting up walls and shutting off from each other when it's the exchange of ideas that has made our nations so prosperous. Brexit provides new options as Britain pivots away from European immigration. Let's approach Britain with a proposal for a two-way free movement agreement".[104]

In April 2018 Simon Bridges MP, then Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the National Party, announced his support for CANZUK.[105]

Leader of the New Zealand First political party Winston Peters called in February 2016 for a Commonwealth Free Trade Area modelled on the one in existence between Australia and New Zealand. In his comments, he suggested the inclusion of the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand in this area, with the possibility of adding others, referring to the putative free trade area as a 'Closer Commonwealth Economic Relations' area, or CCER.[106] CCER was included as New Zealand government policy in the Labour-NZ First coalition agreement.[107]

United Kingdom

On 11 July 2012, Andrew Rosindell MP for Romford put forward a private members' bill to the UK Parliament which would involve allowing "subjects of Her Majesty's realms to enter the United Kingdom through a dedicated channel at international terminals", "display prominently a portrait of Her Majesty as Head of State" and the Union flag, and other provisions,[108] which would include citizens of Canada, Australia and New Zealand, with the stated aim of introducing reciprocal border agreements between the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms in the future.[109] The bill was supported by MPs Nigel Dodds (DUP), Rory Stewart (Conservative), Bob Blackman (Conservative), Steve Baker (Conservative), Priti Patel (Conservative), Mark Menzies (Conservative), Kate Hoey (Labour), Ian Paisley (DUP), John Redwood (Conservative) and Thomas Docherty (Labour).[109] The "Bill failed to complete its passage through Parliament before the end of the session ... and [made] no further progress."[108]

The Adam Smith Institute expressed its support for CANZUK in early 2018.[110][111][112]

Then Conservative Party MEP for South East England Daniel Hannan expressed his support for CANZUK as a guest speaker at the 2018 Canadian Conservative Party convention in Halifax.[113] Scottish Conservative MP Bill Grant also expressed his support for increased ties between the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and New Zealand on his webpage in 2018 and stated that British Ministers are aware of CANZUK and "are very enthusiastic about our future relationships and trade with each of the countries involved".[114]

Since early 2020, the grassroots Conservative Party movement Conservatives for CANZUK has influenced MPs to build support for a post-Brexit realignment of British foreign policy among Conservative Party members, other MPs, peers and policy makers.[115] Open supporters includes 23 MPs among whom notably include Jeremy Hunt and Paul Bristow - chairman of the CANZUK APPG.[116]

Opposing views

Critics have suggested that the CANZUK project would not make sense as a geopolitical construct in the 21st century. Nick Cohen wrote in April 2016 that "It's a Eurosceptic fantasy that the 'Anglosphere' wants Brexit", and emphasises the gradual separation that has occurred between each of the states in both legal and political culture since the end of the British Empire.[117]

Former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd reiterated this sentiment, stating that "much as any Australian, Canadian and New Zealand governments of whichever persuasion would do whatever they could to frame new free-trade agreements with the UK, the bottom line is that 65 million of us do not come within a bull's roar of Britain's adjacent market of 450 million Europeans", describing the idea as "bollocks".[118]

Economic, geographical, political and social complexities would limit the influence that this bloc could exert. Only one of the countries (the United Kingdom) has significant military capabilities, and it is the only one with a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. The UK's economy is considerably bigger than those of each of the three other countries.[119]

Chris Randle wrote in the left-wing Jacobin that "Anglo-conservatives sometimes fantasize about reuniting the dominions under “CANZUK,” a trade bloc where workers could be exploited freely. In Europe's most regionally unequal economy, the United Kingdom, desiccated from years of austerity, this is what passes for political ambition: necromancers sewing each other's zombies together."[120]

Accusations of racism

An editorial in Canada's Globe and Mail, which described CANZUK as "a silly name", pointed out that those Commonwealth countries with which advocates of Brexit were most enamoured were "ex-Dominions where white people predominate" and that even if it were broadened to include populous countries, the group had "nowhere near the latent appetite for trade with Britain that would make the scheme credible".[121] In an article published in The New York Times in April 2018, historian Alex von Tunzelmann stated that "no doubt, the advocates of reviving Britain's links with Canada, Australia and New Zealand can cite myriad reasons that have nothing to do with racism to explain why some other nations are just different. Still, majority-nonwhite nations will notice if they are treated as them rather than us, because this will not be the first time that has happened."[122]

In academia, Duncan Bell criticises contemporary 'Anglospheric discourse' and concludes that modern political commentary is "a pale imitation of previous iterations", lacking support across the political spectrum.[123] International affairs professor Srdjan Vucetic expands on this idea further, describing CANZUK as "the latest variant of a long line of projects seeking to consolidate the British settler empire, projects that were until deep into the second half of the twentieth century justified in explicitly racist terms" and questioned the viability of a CANZUK defence pact without the inclusion of the United States, as in the Five Eyes and ABCANZ alliances.[124]

Official views

On a visit to Australia in September 2019, Liz Truss, then the UK International Trade Secretary, stated that the British government would raise free movement between Australia and the UK during post-Brexit negotiations for a free-trade agreement.[125]

In January 2020, it was reported that Australia's Morrison government was opposed to expanding freedom of movement between Australia and the UK. Australian trade minister Simon Birmingham had said he "can't imagine full and unfettered free movement" would be discussed during post-Brexit negotiations for a free-trade agreement.[126] Former Australian prime minister Scott Morrison had earlier said in September 2019 that "the New Zealand arrangement is quite unique and it's not one we would probably ever contemplate extending".[127]

Public opinion

Although it has maintained a level of support, the concept of CANZUK is generally regarded as highly polarised between the political left and right.[128][129] While it has been praised by British nationalists for being an alternative to the European Union,[130] the proposed union has been critiqued by those on the left. Examples of this are by unfavourably comparing CANZUK to the EU, or criticising it as supposedly being racist for solely combining the United Kingdom and three of its five former "white dominions", to the exclusion of other Anglophone countries where people from the United Kingdom formerly settled, such as India, South Africa, Singapore and Nigeria.[131][132][133][134][135]

2015

Public opinion polling conducted by research firm YouGov in 2015 found that 58 per cent of British people would support freedom of movement and work between the citizens of the United Kingdom and the citizens of Australia, Canada and New Zealand, with 19 per cent opposed to the idea and 23 per cent undecided, with support for the proposals found in all four countries of the United Kingdom.[136] The research also found that British people valued free mobility between the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and New Zealand more than they valued free mobility between the United Kingdom and the European Union at 46 per cent to 35 per cent.[137] Opinion polls from other firms was not published.

2016

Opinion poll surveys commissioned by the Royal Commonwealth Society in 2016 found that 70 per cent of Australians said they were supportive of the proposal, with 10 per cent opposed to it; 75 per cent of Canadians said they supported the idea and 15 per cent were opposed to it and 82 per cent of New Zealanders stated that they supported the idea, with 10 per cent opposed.[137] All of the respective provinces, states and territories of Australia, Canada and New Zealand registered majority support for the proposals.[137]

2017

Further polling of 2,000 people conducted in January 2017 found support for free movement of people and goods with certain limitations on citizens claiming tax-funded payments on entry across Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, with undecideds included. Counting undecideds as giving support makes these results somewhat questionable. Support in Australia was at 72 per cent, 77 per cent in Canada, 81 per cent in New Zealand and 64 per cent in the United Kingdom.[138][139]

2018

A survey carried out by CANZUK International consisting of 13,600 respondents from Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom conducted between January and March 2018 found increased support for reciprocal free trade and movement of people between the countries when compared to 2017, with support at 73 per cent in Australia (up 1 per cent); 76 per cent in Canada (down 1 per cent); 82 per cent in New Zealand (up 1 per cent); and 68 per cent in the United Kingdom (up 4 per cent).[140] The opinion polling indicated greater support for the proposals in the North and South Islands of New Zealand at 83 per cent and 81 per cent support respectively; British Columbia and Ontario in Canada at 82 per cent and 80 per cent support respectively; and New South Wales and Victoria in Australia at 79 per cent support each, while lesser support was observed in Quebec in Canada at 63 per cent support; Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland in the United Kingdom at 64 per cent, 70 per cent and 66 per cent support respectively; and Western Australia at 65 per cent support.[141]

See also

- ABCANZ Armies

- Air Force Interoperability Council

- Anglosphere

- AUKUS

- AUSCANNZUKUS

- Benelux

- Border Five

- British diaspora

- Commonwealth free trade

- Commonwealth realm

- Five Eyes

- Five Nations Passport Group

- Imperial Federation

- JUSCANZ

- Migration 5

- Pacific Union

- Regionalism (international relations)

- Supranational union

- The Technical Cooperation Program

- Customs arrangements with the Crown Dependencies

Notes

- English is a de facto official language due to its widespread use[33]

- Canadian religions are 2021 estimates.[35]

- Australian religions are 2021 estimates.[24]

- New Zealand religions are "based on the 2018 census of the usually resident population; percentages add up to more than 100% because respondents were able to identify more than one."[25]

- As of Q2 2020.

- No permanent population, weather monitoring station generally with four staff.[57]

References

- Andrew Roberts. "CANZUK: after Brexit, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Britain can unite as a pillar of Western civilisation". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Andrew Lilico. "CANZUK is calling. Will Britain respond?". CAPX. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- CANZUK International (November 2020). "CANZUK International: Policies & Campaign Proposals" Archived 5 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Toronto: CANZUK International. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- SRDJAN, VUCETIC (28 January 2021). "Why CANZUK won't work". The Globe and Mail.

- HEISLER, JAY (14 September 2021). "A Radical Idea: CANZUK in Canadian Foreign and Defence Policy". Canadian Global Affairs Institute.

- Adam Smith Institute (July 2019). "CANZUK — A BRIGHT FUTURE GETTING CLOSER" Archived 4 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine. London: Adam Smith Institute. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Henry Jackson Society (February 2019). "Global Britain: A Twenty-First Century Vision" Archived 1 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. London: Henry Jackson Society. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Bruges Group (11 August 2020). "Kiwis and CANZUK: A Bridge Too Far No More?". London: Bruges Group. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Colonies Into Commonwealth Archived 28 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, William David McIntyre, Walker, 1967, page 375

- Global News (21 January 2018). "Push for free movement of Canadians, Kiwis, Britons and Australians gains momentum" Archived 12 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Global News. Canada. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- The Express (2 February 2020). "Britain's plan for post-Brexit union with Canada, Australia and New Zealand REVEALED" Archived 2 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine. The Express. London. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- The Spectator (28 October 2020). "Erin O'Toole on CANZUK: A bolder, bigger, and better Union? | The Spectator's Alternative Conference" YouTube. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- Andrew Lilico (7 August 2016). "From Brexit to CANZUK: A call from Britain to team up with Canada, Australia and New Zealand" Archived 19 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Financial Post. London. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- James C. Bennett (2016). A Time for Audacity: New Options Beyond Europe. Pole to Pole Publishing. ASIN: B01H4U7FAQ. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- Andrew Roberts (13 September 2016). "CANZUK: After Brexit, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Britain can unite as a pillar of Western civilisation" Archived 3 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine. The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- "CANZUK Uniting". CANZUK Uniting. 8 March 2017. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Press release. "PM meeting with PM Morrison" Archived 2 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine(1 December 2018). British Government. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- BBC News. "Justin Trudeau wants 'seamless' UK trade deal after Brexit" Archived 17 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine(18 April 2018)

- BBC News. "New Zealand happy to forget the UK's 'betrayal'" Archived 23 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine(24 May 2018)

- Ardern, Jacinda (20 January 2019). "Whatever Britain decides about its new place in the world, New Zealand stands with you". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- Marshall, Peter James (2001). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-521-00254-7.

- "Everything You Need to Know About the Australia-UK Trade Deal". 15 July 2021.

- "Canada". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 15 June 2020. (Archived 2020 edition)

- "Australia". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 August 2020. (Archived 2020 edition)

- "New Zealand". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 15 June 2020. (Archived 2020 edition)

- "United Kingdom". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 15 June 2020. (Archived 2020 edition)

- Statistics Canada (18 June 2020). "Population estimates, quarterly". Statistics Canada. doi:10.25318/1710000901-eng. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- "Main Features - Key statistics". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- "Estimated Resident Population (Mean Quarter Ended)". Statistics New Zealand. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- "Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland". Office for National Statistics. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- "Sea Around Us | Fisheries, Ecosystems and Biodiversity". www.seaaroundus.org. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2017-18: Population Estimates by Significant Urban Area, 2008 to 2018". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimated resident population, 30 June 2022: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/latest-release.

- , (PDF) (Report). p. 89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015. "In addition to the Māori language, New Zealand Sign Language is also an official language of New Zealand. The New Zealand Sign Language Act 2006 permits the use of NZSL in legal proceedings, facilitates competency standards for its interpretation and guides government departments in its promotion and use. English, the medium for teaching and learning in most schools, is a de facto official language by virtue of its widespread use. For these reasons, these three languages have special mention in the New Zealand Curriculum.".

- , The British Council, 20 March 2023

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (26 October 2022). "Religion by visible minority and generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- "Religion, England and Wales - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- "Military Spending by Country 2022". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- "Projected GDP Ranking (2018-2023)". statisticstimes.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "Global Wealth Report 2017 Databook". Credit Suisse. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018.

- "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). undp.org. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- "Population estimates, quarterly". Statistics Canada. 27 June 2018. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019.

- Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of (18 March 2020). "Population clock". www.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Population clock". archive.stats.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "World Population Prospects - Population Division - United Nations". population.un.org. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "Largest Countries in the World by Area - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- "Northwest Territories Act". Department of Justice Canada. 1986. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Yukon Act". Department of Justice Canada. 2002. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- Department of Justice Canada (1993). "Nunavut Act". Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- "Land and freshwater area, by province and territory". Statistics Canada. 2005. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- Northwest Territories Official Languages Act, 1988 Archived 22 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine (as amended 1988, 1991–1992, 2003)

- "Nunavut's Official Languages". Language Commissioner of Nunavut. 2009. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "OCOL – Statistics on Official Languages in Yukon". Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages. 2011. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "3101.0 – Australian Demographic Statistics, Jun 2019". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 19 December 2019. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Area of Australia – States and Territories". Geoscience Australia: National Location Information. Geoscience Australia. 15 May 2014. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Australia, Geoscience (15 May 2014). "Ashmore and Cariter Islands". Australian Government Geoscience Australia. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "How Willis Island weather observers survive life working at the remote outpost off Queensland". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 28 March 2018. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Pacific Islands and New Zealand – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Hare, McLintock, Alexander; Wellington., Ralph Hudson Wheeler, M.A., Senior Lecturer in Geography, Victoria University of; Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu (1966). "The Ross Dependency". Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Check if you're a New Zealand citizen". New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- "Supporting the Overseas Territories". UK Government. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

There are 14 Overseas Territories which retain a constitutional link with the UK. .... Most of the Territories are largely self-governing, each with its own constitution and its own government, which enacts local laws. Although the relationship is rooted in four centuries of shared history, the UK government's relationship with its Territories today is a modern one, based on mutual benefits and responsibilities. The foundations of this relationship are partnership, shared values and the right of the people of each territory to choose to freely choose whether to remain a British Overseas Territory or to seek an alternative future.

- "British Overseas Territories Law". Hart Publishing. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

Most, if not all, of these territories are likely to remain British for the foreseeable future, and many have agreed modern constitutional arrangements with the British Government.

- "What is the British Constitution: The Primary Structures of the British State". The Constitution Society. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

The United Kingdom also manages a number of territories which, while mostly having their own forms of government, have the Queen as their head of state, and rely on the UK for defence and security, foreign affairs and representation at the international level. They do not form part of the UK, but have an ambiguous constitutional relationship with the UK.

- "New ministerial appointments at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office" (Press release). Foreign and Commonwealth Office. 19 July 2016. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- "Anguilla Population 2019". Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "British Antarctic Territory". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "Bermuda Population 2019". Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "UNdata | record view | Surface area in km2". United Nations. 4 November 2009. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "Commonwealth Secretariat – British Antarctic Territory". Thecommonwealth.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "Commonwealth Secretariat – British Indian Ocean Territory". Thecommonwealth.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "British Indian Ocean Territory". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "British Virgin Islands". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 14 August 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- "Economics and Statistics Office - Labour Force Survey Report Spring 2018" (PDF). www.eso.ky. Cayman Islands Economics and Statistics Office. August 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Falkland Islands Population 2019". Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Gibraltar Population 2019". Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Gibraltar". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "Montserrat". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 14 August 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- "Pitcairn Islands Tourism | Come Explore... The Legendary Pitcairn Islands". Visitpitcairn.pn. Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- "Pitcairn Residents" Archived 7 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. puc.edu. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- "Pitcairn Island". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "St Helena Government". St Helena Government. 30 July 2019. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- "St Helena, Ascension, Tristan da Cunha profiles". BBC. 16 March 2016. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- "Population of Grytviken, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands". Population.mongabay.com. 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 11 June 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- "SBA Cyprus". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "Turks and Caicos Islands Population 2019". Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Turks and Caicos Islands". Jncc.gov.uk. 1 November 2009. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- "Crown Dependencies – Justice Committee". Parliament of the United Kingdom. 30 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- "Background briefing on the Crown dependencies: Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man" (PDF). Ministry of Justice. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- "Fact sheet on the UK's relationship with the Crown Dependencies" (PDF). Ministry of Justice. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Government Response to the Justice Select Committee's report: Crown Dependencies" (PDF). Ministry of Justice. November 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- "Profile of Jersey". States of Jersey. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 31 July 2008.

The legislature passes primary legislation, which requires approval by The Queen in Council, and enacts subordinate legislation in many areas without any requirement for Royal Sanction and under powers conferred by primary legislation.

- CANZUK International Archived 23 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- CANZUK Uniting Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- "Pro-CANZUK Politician Elected As Federal Party Leader". CANZUK International. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Erin O'Toole campaign website – "CANZUK"". Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Erin O'Toole for Leader/pour chef (18 February 2017), James Skinner and Erin O'Toole on CANZUK, archived from the original on 12 March 2017, retrieved 28 May 2018

- "CANZUK". Erin O'Toole. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "Canadian Conservatives Vote Overwhelmingly to Implement a CANZUK Treaty - CPC Convention 2018". Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2018 – via www.youtube.com.

- Bateman, Sophie (28 August 2018). "Canada Conservatives vote for free movement, trade with New Zealand". Newshub. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "CANZUK". Erin O'Toole. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Lao, David (24 August 2020). "Erin O'Toole: A look at the new Conservative leader and what he is promising". Global News.

- "Let's fold UK and Canada into the Closer Economic Relations treaty". Senator James Paterson. 28 August 2017. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ACT New Zealand (October 2016). "ACT proposes free movement with Britain, Oz and Canada" Archived 9 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Scoop News. Auckland. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- "New Zealand Opposition Leader Backs CANZUK International's Campaign". CANZUK International. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- "Winston Peters calls for free trade among Commonwealth". NZHerald.co.nz. 24 February 2016. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Lilico, Andrew (24 October 2017). "New Zealand is taking the initiative on trade — Brexit Britain should respond in kind". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "United Kingdom Borders Bill 2012-13". Parliament of the United Kingdom. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

A Bill to allow subjects of Her Majesty's realms to enter the United Kingdom through a dedicated channel at international terminals, to ensure that all points of entry to the United Kingdom at airports, ports and terminals display prominently a portrait of Her Majesty as Head of State, the Union Flag and other national symbols; to rename and re-establish the UK Border Agency as 'Her Majesty's Border Police'; and to enhance the Agency's powers to protect and defend the borders of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

- "House of Commons: Oral Answers to Questions". Parliament of the United Kingdom. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Dr. Madsen Pirie (31 January 2018). "Some things that are not right about the Britain of today". Adam Smith Institute. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Matt Kilcoyne (16 April 2018). "Our CANZUK friends should be welcome in post-Brexit Britain". City A.M. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Dr. Madseon Pirie (17 April 2018). "Yes we CANZUK". Adam Smith Institute. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Daniel Hannan (20 September 2018). "Speech at Conservative Party's 2018 convention in Halifax". YouTube. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Bill Grant MP. "Foreign and Commonwealth Office". Archived from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Conservatives for CANZUK". Conservatives for CANZUK. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the UK (CANZUK) APPG". www.parallelparliament.co.uk. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Nick Cohen (12 April 2016). "It's a Eurosceptic fantasy that the 'Anglosphere' wants Brexit". Archived 19 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Spectator. London. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- "Think the Commonwealth can save Brexit Britain? That's utter delusion" Archived 30 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine (11 March 2019). The Guardian.

- Dunham, Jackie (15 December 2018). "Increased push for free movement between Canada, U.K., Australia, New Zealand". CTV News. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Modern Cities Are Haunted by the Ghost of British Empire". jacobin.com.

- With Brexit looming, Britain suddenly remembers the Commonwealth Archived 26 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine,Globe and Mail, 20 April 2018

- von Tunzelmann, Alex (24 April 2018). "The Empire Haunts Britain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- Duncan Bell (2016). 'The Project for a New Anglospheric Century' in Reordering the World: Essays on Liberalism and Empire. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13878-7. Retrieved 24 November 2016. 206-207.

- Bell, Duncan; Vucetic, Srdjan (9 November 2018). "Brexit, CANZUK and the Legacy of Empire". SocArXiv: 29. doi:10.31235/osf.io/qw25z. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019.

- "Britain will aim for freedom of movement deal with Australia". The Guardian. 19 September 2019. Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "Morrison government rules out visa-free travel between Australia, UK". The Sydney Morning Herald. 6 January 2020. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "UK flags possibility of freedom of movement deal with Australia". News.com.au. 18 September 2019. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "CANZUK: A new Commonwealth agreement? - The Lawyer's Daily". www.thelawyersdaily.ca. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- Kohnert, Dirk (8 December 2021). "Munich Personal RePEc Archive The socio-economic impact of Brexit on CANZUK and the Anglosphere in times of Corona : The case of Canada, Australia and New Zealand" (PDF).

- Peacock, Colin (28 August 2020). "Dark money, democracy and the media". RNZ. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "Brexit, CANZUK, and the Legacy of Empire". repository.cam.ac.uk.

- Holden, Lewis (23 February 2020). "A post-Brexit bloc of former colonies is the answer to a question no one asked". The Spinoff. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- "Why 'CANZUK' is an absurd fantasy". UnHerd. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Why is the Anglosphere hated? | Bruce Newsome". The Critic Magazine. 15 September 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- Holden, Lewis (23 February 2020). "A post-Brexit bloc of former colonies is the answer to a question no one asked". The Spinoff. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "YouGov | Freedom of movement within Commonwealth more popular than within EU". YouGov: What the world thinks. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "UK public strongly backs freedom to live and work in Australia, Canada and New Zealand" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- "Survey Reveals Support For CANZUK Free Movement". CANZUK International. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Kilcoyne, Matt (16 April 2018). "Our CANZUK friends should be welcome in post-Brexit Britain". Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Latest Poll Shows Significant Public Support For CANZUK Free Movement". CANZUK International. 16 April 2018. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "CANZUK International – "National and Regional Polling Results - April 2018"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)