Armbruster's wolf

Armbruster's wolf (Canis armbrusteri) is an extinct species that was endemic to North America and lived during the Irvingtonian stage[1] of the Pleistocene epoch, spanning from 1.9 Mya—250,000 years BP.[2] It is notable because it is proposed as the ancestor of one of the most famous prehistoric carnivores in North America, the dire wolf, which replaced it.[1]

| Armbruster's wolf Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene-Late Pleistocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | †C. armbrusteri |

| Binomial name | |

| †Canis armbrusteri J. W. Gidley, 1913 | |

| |

| Range of Armbruster's wolf based on fossil distribution | |

Taxonomy

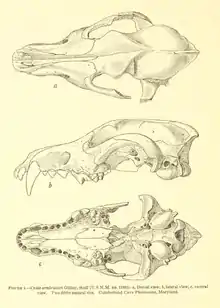

Canis armbrusteri was named by James W. Gidley in 1913. The first fossils were uncovered at Cumberland Bone Cave, Maryland, in an Irvingtonian terrestrial horizon. Fossil distribution is widespread throughout the United States.[3]

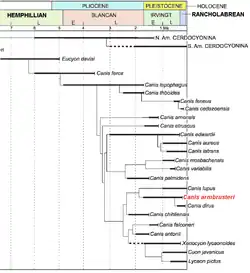

Middle Pleistocene in North America.[4] The North American wolves became larger, with tooth specimens indicating that C. priscolatrans diverged into the large wolf C. armbrusteri.[5]: p242 [6] R. A. Martin disagreed, and believed that C. armbrusteri[7] was C. lupus.[8] Ronald M. Nowak disagreed with Martin and proposed that C. armbrusteri was not related to C. lupus but C. priscolatrans, which then gave rise to C. dirus. Richard H. Tedford proposed that the South American C. gezi and C. nehringi share dental and cranial similarities developed for hypercarnivory, suggesting C. armbrusteri was the common ancestor of C. gezi, C. nehringi and C. dirus.[1]: 148 Based on morphology from China, the Pliocene wolf C. chihliensis may have been the ancestor for both C. armbrusteri and C. lupus before their migration into North America.[9]: p148 [1]: p181 C. armbrusteri appeared in North America in the Middle Pleistocene and is a wolf-like form larger than any Canis at that time.[4]

The three noted paleontologists X. Wang, R. H. Tedford and R. M. Nowak have all proposed that C. dirus had evolved from C. armbrusteri,[1]: 181 [9]: p52 with Nowak stating that there were specimens from Cumberland Cave, Maryland that indicated C. armbrusteri diverging into C. dirus.[10][5]: p243 The two taxa share a number of characteristics (synapomorphy), which suggests an origin of dirus in the late Irvingtonian in the open terrain in the midcontinent, and then later expanding eastward and displacing armbrusteri.[1]: 181

In 2021, researchers sequenced the nuclear DNA (from the cell nucleus) of the dire wolf. The sequences indicate the dire wolf to be a highly divergent lineage which last shared a most recent common ancestor with the wolf-like canines 5.7 million years ago, with morphological similarities with the grey wolf being convergent evolution. The study's findings are consistent with the previously proposed taxonomic classification of the dire wolf as genus Aenocyon. The study proposes an early origin of the dire wolf lineage in the Americas, and that this geographic isolation allowed them to develop a degree of reproductive isolation since their divergence 5.7 million years ago. Coyotes, dholes, gray wolves, and the extinct Xenocyon evolved in Eurasia and expanded into North America relatively recently during the Late Pleistocene, therefore there was no admixture with the dire wolf. The long-term isolation of the dire wolf lineage implies that other American fossil taxa, including C. armbrusteri and C. edwardii, may also belong to the dire wolf's lineage.[11]

References

- Tedford, Richard H.; Wang, Xiaoming; Taylor, Beryl E. (2009). "Phylogenetic Systematics of the North American Fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae)" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 325: 1–218. doi:10.1206/574.1. S2CID 83594819.

- The _Blancan, Irvingtonian and Rancholabrean Mammal Ages by Christopher J. Bell and Ernest L. Lundelius Jr., Anthony D. Barnosky, Russell W. Graham, Everett H. Lindsay, Dennis R. Ruez Jr., Holmes A. Semken Jr., S. David Webb, and Richard J. Zakrzewski. January 2004 in the book: Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic Mammals of North America: Biostratigraphy and Geochronology. Chapter: 7. Publisher: Columbia University Press; Editors: Michael O. Woodburne. pp274-276

- Preliminary report on a recently discovered Pleistocene cave deposit near Cumberland, Maryland, JW Gidley - 1913 - US Government Printing Office

- R. M. Nowak. 1979. North American Quaternary Canis. Monograph of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 6:1-154 LINK:

- R.M. Nowak (2003). "Chapter 9 - Wolf evolution and taxonomy". In Mech, L. David; Boitani, Luigi (eds.). Wolves: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. pp. 239–258. ISBN 0-226-51696-2.

- Berta, A. 1995. Fossil carnivores from the Leisey Shell Pits, Hillsborough County, Florida. In R.C. Hulbert, Jr., G.S. Morgan, and S.D. Webb (editors), Paleontology and geology of the Leisey Shell Pits, early Pleistocene of Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37: 463–499.

- Fossilworks website Canis armbrusteri

- Martin, R. A., and S. D. Webb (1974). Late Pleistocene mammals from the Devil's Den fauna, Levy County p114-45 in S. D. Webb (ed.), Pleistocene Mammals of Florida, Gainesville: University Presses of Florida

- Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H.; Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

- Nowak, R. M. and Federoff, N. E. (2002). The systematic status of the Italian wolf Canis lupus. Acta theriol. 47(3): 333-338

- Perri, Angela R.; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Mouton, Alice; Álvarez-Carretero, Sandra; Hulme-Beaman, Ardern; Haile, James; Jamieson, Alexandra; Meachen, Julie; Lin, Audrey T.; Schubert, Blaine W.; Ameen, Carly; Antipina, Ekaterina E.; Bover, Pere; Brace, Selina; Carmagnini, Alberto (2021-03-04). "Dire wolves were the last of an ancient New World canid lineage". Nature. 591 (7848): 87–91. Bibcode:2021Natur.591...87P. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03082-x. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 33442059. S2CID 231604957.