Bunkeya

Bunkeya is a community in the Lualaba Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is located on a huge plain near the Lufira River. Before the Belgian colonial conquest, Bunkeya was the center of a major trading state under the ruler Msiri.[1]

Bunkeya | |

|---|---|

Map showing Msiri's kingdom, with Bunkeya as capital, and the route taken by the Stairs Expedition of 1891 / 1892 | |

| Coordinates: 10.397434°S 26.968059°E | |

| Country | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Province | Lualaba Province |

Early history

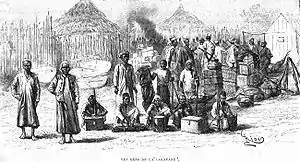

In the later 19th-century, Bunkeya was the capital of Msiri, the son of an East African trader. Msiri's father had been in the business of buying copper ore in Katanga and transporting it to the east coast of Africa for resale. As a young man Msiri remained behind in the region as his father's agent. He became leader of a group of Bayeke people, and established a state that extended from the Luapula River south to the Congo-Zambezi watershed, and from Lake Mweru in the east to the Lualaba River in the west. Based on Bunkeya, the state controlled a huge central-African trading network, mostly dealing in slaves but also in ivory, salt, copper and iron ore. Traders came to Bunkeya from the Zambezi and Congo basins, from Angola, Uganda and Zanzibar. The Arabs from the east coast bought guns and ammunition, which Msiri used to maintain his position.[1]

European contacts

The German scientist Paul Reichard was the first European to reach Bunkeya, arriving on 20 January 1884. He was followed by Capello and Ivens, two Portuguese explorers seeking a trade route to link Angola and Mozambique.[1] In February 1886 the Scottish missionary Frederick Stanley Arnot arrived at Bunkeya unaccompanied and without food or trade goods. Msiri welcomed him and let him settle, but discouraged him from teaching his religion.[2]

Later, several other missionaries joined Arnot.[2] In 1887, William Henry Faulknor, a young Canadian from Hamilton, Ontario who had joined the Plymouth Brethren evangelical movement, arrived at Bunkeya.[3] Another member of the Brethren, Dan Crawford, arrived in 1890 and was to be a witness to Msiri's assassination.[4] Msiri employed Faulknor and other missionaries as "errand boys", symbols of his influence, while Faulknor taught and converted a small group of redeemed slaves.[5]

Although the territory had been ceded to Belgium under the Berlin Conference (1884), Cecil Rhodes began taking an interest and sent agents to Katanga.[2] In 1890 Rhodes sent Alfred Sharpe to Bunkeya to try to obtain a treaty with Msiri. One of the missionaries, acting as an interpreter and witness, read the complete text. Msiri was furious when he heard what he was being asked to agree to, and Sharpe was forced to make a hasty departure to save his life.[6]

Unaware of this, and responding to the British challenge, King Leopold II of Belgium dispatched three expeditions to Bunkeya. The first, 300 people under Paul Le Marinel coming from Lusambo, crossed the Lualaba in March 1891, where they met a representative of Msiri.[7] Continuing south, on 18 April 1891 they reached Bunkeya and were received courteously by Msiri. Le Marinel spent seven weeks at Bunkeya, but was unable to persuade Msiri to formally accept Belgian authority. He left a small garrison nearby to observe developments and returned to Lusambo, arriving on 18 August 1891.[7] Another expedition under Alexandre Delcommune reached Bunkeya later that year, but had no more success.[8]

Conquest and later years

The third expedition, the Stairs Expedition to Katanga, was decisive. At the age of 25 the Canadian-born engineer, soldier and mercenary William Grant Stairs had been second in command of Henry Morton Stanley's 1887 expedition to relieve Emin Pasha in Equatoria. In 1891 he was commissioned to lead an expedition of 336 porters and askaris from Zanzibar to Bunkeya to obtain Msiri's submission.[9] Stairs demanded that Msiri accept the sovereignty of Leopold II over his territory. Msiri again refused and fled to a nearby village where he was killed by Omer Bodson, a member of Stairs' force. Resistance ceased and Katanga came under Belgian rule.[10]

The death of Msiri ended a rule that had become tyrannical, but also destroyed political stability. Trading caravans no longer came to Bunkeya, the local people suffered from famine and disease, and many left the town.[11] The Belgians recognized one of Msiri's sons, Mukanda Bantu, as his successor.[12] Stairs had accepted Mukanda Bantu as Msiri's chosen heir, but restricted him to the territory immediately surrounding Bunkeya and removed all real power.[13] Over the next few years the Belgians established their authority in the region and began exploiting its huge mineral resources.[11]

The Belgians forced Mukanda Bantu and his followers to move to Lukafu, where they stayed for eighteen years before being allowed to return. The situation gradually improved, with piped potable water being available under the leadership of Musamfya Ntanga (1940–1956). After 1976, the population grew fast. Agriculture is productive, yielding crops of maize, cassava, sweet potatoes, legumes and peanuts. However, the water supply is insufficient and health care is inadequate, with few people able to afford drugs. The village does have a hospital and a tuberculosis clinic.[14]

References

- Gondola 2002, p. 62.

- Gondola 2002, p. 63.

- Wilson 2007, p. 40.

- Gordon 2006, p. 104.

- Rotberg 1964, pp. 285–297.

- Ewans 2002, p. 135.

- Moloney 2007, p. 20.

- Meuris 2001.

- Moloney 2007, p. ix.

- Moloney 2007, p. x.

- Gondola 2002, p. 64.

- Philips 2006, p. 458.

- Cultures et développement.

- Bunkeya.

Sources

- "Bunkeya". Mwami Msiri, King of Garanganze. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- Cultures et développement (1835-1969) (in French). Vol. 11. Université catholique de Louvain. 1979.

- Ewans, Martin (2002). European atrocity, African catastrophe: Leopold II, the Congo Free State and its aftermath. Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1589-4.

- Gondola, Ch. Didier (2002). The history of Congo. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 62. ISBN 0-313-31696-1.

- Gordon, David M. (2006). Nachituti's gift: economy, society, and environment in central Africa. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-21364-1.

- Meuris, Christine (2001). "SCRAMBLE FOR KATANGA". Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- Moloney, Joseph A. (2007). With Captain Stairs to Katanga: Slavery and Subjugation in the Congo 1891-92. Jeppestown Press. ISBN 978-0-9553936-5-5.

- Philips, John Edward (2006). Writing African History. University Rochester Press. ISBN 1-58046-256-1.

- Rotberg, Robert I. (1964). "Plymouth Brethren and the Occupation of Katanga, 1886-1907". The Journal of African History. 5 (2): 285–297. doi:10.1017/s0021853700004849.

- Wilson, T. Ernest (2007). Angola Beloved. Gospel Folio Press. ISBN 978-1897117446.