Buck v. Bell

Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., in which the Court ruled that a state statute permitting compulsory sterilization of the unfit, including the intellectually disabled, "for the protection and health of the state" did not violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[1] Despite the changing attitudes in the coming decades regarding sterilization, the Supreme Court has never expressly overturned Buck v. Bell.[2] It is widely believed to have been weakened by Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942), which involved compulsory sterilization of male habitual criminals (and came to a contrary result).[3][4] Legal scholar and Holmes biographer G. Edward White, in fact, wrote, "the Supreme Court has distinguished the case [Buck v. Bell] out of existence".[5] In addition, federal statutes, including the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, provide protections for people with disabilities, defined as both physical and mental impairments.

| Buck v. Bell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued April 22, 1927 Decided May 2, 1927 | |

| Full case name | Carrie Buck v. John Hendren Bell, Superintendent of State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble Minded |

| Citations | 274 U.S. 200 (more) 47 S. Ct. 584; 71 L. Ed. 1000 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Buck v. Bell, 143 Va. 310, 130 S.E. 516 (1925) |

| Holding | |

| The Court upheld a statute instituting compulsory sterilization of the unfit "for the protection and health of the state." Supreme Court of Virginia affirmed. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Holmes, joined by Taft, Van Devanter, McReynolds, Brandeis, Sutherland, Sanford, Stone |

| Dissent | Butler |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. XIV | |

Superseded by | |

| Skinner v. Oklahoma (partially, 1942) | |

| Part of a series on |

| Eugenics in the United States |

|---|

|

Background

The concept of eugenics was propounded in 1883 by Francis Galton, who also coined the name.[6] The idea first became popular in the United States and had found proponents in Europe by the start of the 20th century; 42 of the 58 research papers presented at the First International Congress of Eugenics, held in London in 1912, were from American scientists.[7] Indiana passed the first eugenics sterilization statute in 1907, but it was legally flawed. To remedy that situation, Harry Laughlin, of the Eugenics Record Office (ERO) at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, designed a model eugenic law that was reviewed by legal experts. In 1924, the Commonwealth of Virginia adopted a statute authorizing the compulsory sterilization of the intellectually disabled for the purpose of eugenics, a statute closely based on Laughlin's model.[8][9]

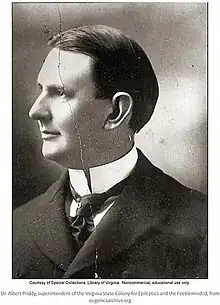

Dr. Albert Sidney Priddy, superintendent[10] of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, could fairly be described as a zealot of eugenics. Prior to 1924, Priddy had performed hundreds of forced sterilizations by creatively interpreting laws which allowed surgery to benefit the "physical, mental or moral" condition of the inmates at the Colony. He would operate to relieve "chronic pelvic disorder" and, in the process, sterilize the women. According to Priddy, the women he chose were "immoral" because of their "fondness for men," their reputations for "promiscuity," and their "over-sexed" and "man-crazy" tendencies. One sixteen-year-old girl was sterilized for her habit of "talking to the little boys."

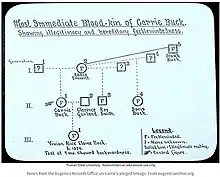

Looking to determine if the new law would survive a legal challenge, on September 10, 1924, Priddy filed a petition with his board of directors to sterilize Carrie Buck. She was an 18-year-old patient at his institution who he claimed had a mental age of 9.[11] Priddy maintained that Buck represented a genetic threat to society. According to him, Buck's 52-year-old mother possessed a mental age of 8, had a record of prostitution and immorality, and had three children without good knowledge of their paternity. Carrie Buck, one of those children, had been adopted and attended school for five years, reaching the level of sixth grade.[12] However, according to Priddy, Buck eventually proved to be "incorrigible" and gave birth to an illegitimate child. Her adoptive family had her committed to the State Colony as "feeble-minded", feeling they were no longer capable of caring for her. It was later claimed that Buck's pregnancy was not caused by any "immorality" on her own part. In the summer of 1923, while her adoptive mother was away "on account of some illness," her adoptive mother's nephew allegedly raped Buck, and her later commitment has been described as an attempt by the family to save their reputation.[13][14]

Buck family

Carrie Buck was born in Charlottesville, Virginia, the first of three children born to Emma Buck; she also had a half-sister, Doris Buck, and a half-brother, Roy Smith.[15] Little is known about Emma Buck except that she was poor and married to Frederick Buck, who abandoned her early in their marriage. Emma was committed to the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded after being accused of "immorality", prostitution, and having syphilis.[16]

After her birth, Carrie Buck was placed with foster parents, John and Alice Dobbs. She attended public school, where she was noted to be an average student.[17] When she was in sixth grade, the Dobbses removed her to have her help with housework.[17][16]

At 17, Buck became pregnant as a result of being raped by Alice Dobbs' nephew, Clarence Garland.[13][15] On January 23, 1924, the Dobbses had her committed to the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded on the grounds of feeblemindedness, incorrigible behavior, and promiscuity. Her commitment is said to have been due to the family's embarrassment at Buck's pregnancy from the rape incident.[16]

On March 28, 1924, she gave birth to a daughter.[17] Since Buck had been declared mentally incompetent to raise her child, the Dobbses adopted the baby and named her "Vivian Alice Elaine Dobbs". She attended Venable Public Elementary School of Charlottesville for four terms, from September 1930 until May 1932. By all accounts, Vivian was of average intelligence, far above feeblemindedness.[16]

She was a perfectly normal, quite average student, neither particularly outstanding nor much troubled. In those days before grade inflation, when C meant "good, 81–87" (as defined on her report card) rather than barely scraping by, Vivian Dobbs received A's and B's for deportment and C's for all academic subjects but mathematics (which was always difficult for her, and where she scored a D) during her first term in Grade 1A, from September 1930 to January 1931. She improved during her second term in 1B, meriting an A in deportment, C in mathematics, and B in all other academic subjects; she was placed on the honor roll in April 1931. Promoted to 2A, she had trouble during the fall term of 1931, failing mathematics and spelling but receiving A in deportment, B in reading, and C in writing and English. She was "retained in 2A" for the next term – or "left back" as we used to say, and scarcely a sign of imbecility as I remember all my buddies who suffered a similar fate. In any case, she again did well in her final term, with B in deportment, reading, and spelling, and C in writing, English, and mathematics during her last month in school. This daughter of "lewd and immoral" women excelled in deportment and performed adequately, although not brilliantly, in her academic subjects.

— Stephen Jay Gould, Natural History magazine (1984),[16] as reprinted in Gould, Stephen Jay, The Flamingo's Smile: Reflections in Natural History, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1985, pp. 316-317.

In June 1932, Vivian contracted measles. She died from a secondary intestinal infection, enteric colitis, at the age of 8.

Trial

Virginia's General Assembly passed the Eugenical Sterilization Act in 1924. According to American historian Paul A. Lombardo, politicians wrote the law to benefit a malpracticing doctor avoiding lawsuits from patients who had been the victims of forced sterilization.[19] Eugenicists used Buck to legitimize this law in the 1927 Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell through which they sought to gain legal permission for Virginia to sterilize Buck.[19][20]

Carrie Buck found herself in the Colony in June of 1924, shortly before her 18th birthday. Priddy quickly made the connection between Emma and Carrie, and he knew about the recently born Vivian: the board of directors issued an order for the sterilization of Buck and her guardian appealed the case to the Circuit Court of Amherst County.

In order to fully validate the law to Priddy’s satisfaction, the Board’s determination had to be defended in court. Thus, Irving P. Whitehead was appointed to “defend” Carrie from the Board’s ruling. Whitehead was not only a close friend of Priddy, a former member of the Colony Board and, unsurprisingly, a staunch believer in forced sterilization, but also a childhood friend of Aubrey E. Strode, who drafted the 1924 Eugenical Sterilization Act.[20][21]

While the litigation was making its way through the court system, Priddy died and his successor, John Hendren Bell, took up the case.[22]

Throughout Carrie's trial, a succession of witnesses offered testimony that was hearsay, contentious, speculative, and simply absurd. Because Priddy and Strode felt it crucial to establish that Carrie's entire family "stock" was defective, witnesses who had never met Carrie testified to rumors and anecdotes surrounding her and her family. One of the few witnesses to testify with first‐hand knowledge of Carrie, a nurse from Charlottesville who had intermittent contact with Carrie over the years, recalled that in grammar school Carrie had been caught writing notes to boys. Priddy, of course, had once sterilized a girl for that transgression. For his testimony, Priddy felt the need to point out that Carrie had a “rather badly formed face.”

Whitehead failed to adequately defend Buck and counteract the prosecutors.[19] Not only did he call no witnesses, but he did not challenge the prosecution’s witnesses’ lack of firsthand knowledge or their dodgy scientific claims. Whitehead did not even call Carrie’s teachers, who could have proven, with documented evidence, that Carrie had been an average student, including one teacher who wrote that Carrie was “very good” at “deportment and lessons.” Instead, it seemed that Whitehead was often testifying against his own client, taking it for granted that she was of “low caliber.” He did not challenge the claim that Carrie was illegitimate, which was false as a matter of Virginia state law because Carrie’s parents were married at the time of her birth. Nor did he argue that Carrie’s supposed “immorality” and Vivian’s illegitimacy were due to a rape by the Dobbs’ nephew, Clarence Garland.

Buck lost in the trial court, where noted Virginia eugenicist Joseph DeJarnette testified against her.[23]

The case then moved to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, where Whitehead offered a 5‑page compared to the state’s 40‐page brief. Buck lost there too. Her only recourse was to the U.S. Supreme Court, but that was merely an illusion: even if Whitehead had put forth an effort, Carrie’s case was put before a Supreme Court with at least two avowed believers in eugenics: Chief Justice (and former president) William Howard Taft and Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. In 1915, Taft had written the introduction to the book How to Live, which contained a sizable portion devoted to eugenics. As for Holmes, in 1921, he told future justice Felix Frankfurter that he had no problem “restricting propagation by the undesirables and putting to death infants that didn’t pass the examination.”

Buck and her guardian contended that the due process clause guarantees all adults the right to procreate which was being violated. They also made the argument that the Equal Protection Clause in the 14th Amendment was being violated since not all similarly situated people were being treated the same. The sterilization law was only for the "feeble-minded" at certain state institutions and made no mention of other state institutions or those who were not in an institution.

The legal challenge was consciously collusive, brought on behalf of the state to test the legality of the statute.[24] The cross examination and witnesses produced by Whitehead were ineffectual and allegedly a result of his alliance with Strode during the trial.[25] There was no real litigation between the prosecution and the defense, and thus the Supreme Court did not receive sufficient evidence to make a fair decision on the "friendly [law]suit."[26]

On May 2, 1927, in an 8–1 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court accepted that Buck, her mother and her daughter were "feeble-minded" and "promiscuous,"[27] and that it was in the state's interest to have her sterilized. The ruling found that the Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924 did not violate the U.S. Constitution and legitimized the sterilization procedures until they were repealed in 1974.

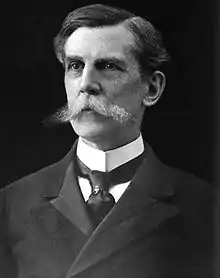

Taft assigned the opinion to Holmes, who went at his task with a zealotry that bordered on bloodlust. His first draft was apparently even more brutal and was criticized by colleagues for substituting rhetorical flourishes about eugenics for legal analysis.

Some of the brethren [the other justices] are troubled about the case, especially [Justice Pierce] Butler. May I suggest that you make a little full [the explanation of] the care Virginia has taken in guarding against undue or hasty action, proven absence of danger to the patient, and other circumstances tending to lessen the shock that many feel over the remedy? The strength of the facts in three generations of course is the strongest argument.

— Chief Justice William Howard Taft, Liva Baker, The Justice from Beacon Hill (1991), ISBN 978-0060166298

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes made clear that the challenge was not upon the medical procedure involved, but on the process of the substantive law. The court was satisfied that the Virginia Sterilization Act complied with the requirements of due process, since sterilization could not occur until a proper hearing had occurred, at which the patient and a guardian could be present, and the patient had the right to appeal the decision. They also found that, since the procedure was limited to people housed in state institutions, it did not deny the patient equal protection of the law. And finally, since the Virginia Sterilization Act was not a penal statute, the Court held that it did not violate the Eighth Amendment, since it is not intended to be punitive. Citing the best interests of the state, Justice Holmes affirmed the value of a law like Virginia's in order to prevent the nation from being "swamped with incompetence." The Court accepted without evidence that Carrie and her mother were promiscuous, and that the three generations of Bucks shared the genetic trait of feeblemindedness. Thus, it was in the state's best interest to have Carrie Buck sterilized.[28] The decision was seen as a major victory for eugenicists.[24]

We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. [...] Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

— Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927)[28]

Holmes concluded his argument by citing Jacobson v. Massachusetts as a precedent for the decision, stating "Three generations of imbeciles are enough".[29][30] The sole dissenter in the court, Justice Pierce Butler, a devout Catholic,[31] did not write a dissenting opinion.

According to famed eugenicist Harry H. Laughlin, whose written testimony was presented during the trial in his absence, Buck's legal defeat signaled the end of "eugenical sterilization's 'experimental period.'"[32] Following the Supreme Court ruling, over two dozen states enacted similar laws, including Oregon and the Carolinas, doubling American sterilizations from 6,000 to more than 12,000 by 1947.[32][33] Buck was sterilized on October 19, 1927, roughly five months after the Supreme Court trial verdict.[20] She became the first Virginian sterilized since the 1924 Eugenical Sterilization Act passed.[20] The Virginia sterilization law is said to have inspired Nazi Germany's 400,000 sterilizations, including those sanctioned under the 1933 Law for Protection Against Genetically Defective Offspring.[33][34]

Carrie Buck was operated upon, receiving a compulsory salpingectomy (a form of tubal ligation). She was later paroled from the institution as a domestic worker to a family in Bland, Virginia. She was an avid reader until her death in 1983. Her daughter Vivian had been pronounced "feeble minded" after a cursory examination by ERO field worker Dr. Arthur Estabrook.[8] According to his report, Vivian "showed backwardness",[8] thus the "three generations" of the majority opinion. It is worth noting that the child did very well in school for the two years that she attended (she died of complications from measles in 1932), even being listed on her school's honor roll in April 1931.[8]

Effects

The effect of Buck v. Bell was to legitimize eugenic sterilization laws in the United States as a whole. While many states already had sterilization laws on their books, their use was erratic and effects practically non-existent in every state except for California. After Buck v. Bell, dozens of states added new sterilization statutes, or updated their constitutionally non-functional ones already enacted, with statutes which more closely mirrored the Virginia statute upheld by the Court.[35]

The Virginia statute that Buck v. Bell upheld was designed in part by the eugenicist Harry H. Laughlin, superintendent of Charles Benedict Davenport's Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York. Laughlin had, a few years previously, conducted studies on the enforcement of sterilization legislation throughout the country and had concluded that the reason for their lack of use was primarily that the physicians who would order the sterilizations were afraid of prosecution by patients upon whom they operated. Laughlin saw the need to create a "Model Law"[36] that could withstand constitutional scrutiny, clearing the way for future sterilization operations. The Nazi jurists designing the German Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring based it largely on Laughlin's "Model Law", although development of that law preceded Laughlin's. Nazi Germany held Laughlin in such high regard that they arranged for him to receive an honorary doctorate from Heidelberg University in 1936. At the Subsequent Nuremberg trials after World War II, counsel for SS functionary Otto Hofmann explicitly cited Holmes's opinion in Buck v. Bell in his defense.[37]

Sterilization rates under eugenic laws in the United States climbed from 1927 until Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942). While Skinner v. Oklahoma did not specifically overturn Buck v. Bell, it created enough of a legal quandary to discourage many sterilizations. By 1963, sterilization laws were almost wholly out of use, though some remained officially on the books for many years. Language referring to eugenics was removed from Virginia's sterilization law, and the current law, passed in 1988 and amended in 2013, authorizes only the voluntary sterilization of those 18 and older, after the patient has given written consent and the doctor has informed the patient of the consequences as well as alternative methods of contraception.[3][38]

The story of Carrie Buck's sterilization and the court case was made into a television drama in 1994, Against Her Will: The Carrie Buck Story. It was also referred to in 1934's sensational film Tomorrow's Children, and was covered in the October 2018 American Experience documentary "The Eugenics Crusade".

Although this opinion and eugenics remain widely condemned, the decision in the case has not been formally overturned. Buck v. Bell was cited as a precedent by the opinion of the court (part VIII) in Roe v. Wade, but not in support of abortion rights. To the contrary, Justice Blackmun quoted it to justify that the constitutional right to abortion is not unlimited.[39] Blackmun claimed that the right to privacy was strong enough to prevent the state from protecting unborn life in the womb, but not strong enough to prevent a woman being sterilized against her will.

In the 1996 case of Fieger v. Thomas, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit both recognized and criticized Buck v. Bell by writing, "as Justice Holmes pointed out in the only part of Buck v. Bell that remains unrepudiated, a claim of a violation of the Equal Protection Clause based upon selective enforcement 'is the usual last resort of constitutional arguments'".[40] In 2001, the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit cited Buck v. Bell to protect the constitutional rights of a woman coerced into sterilization without procedural due process.[41] The court stated that error and abuse will result if the state does not follow the procedural requirements, established by Buck v. Bell, for performing an involuntary sterilization.[41]

Derek Warden has shown how the decision in Buck v. Bell has been affected by the Americans with Disabilities Act.[42]

See also

- Eugenics in the United States

- Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924

- Racial Integrity Act of 1924

- Stump v. Sparkman (1978)

- Poe v. Lynchburg Training School and Hospital (1981)

- Sex-related court cases in the United States

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 274

- Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

References

Notes

Citations

- Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927).

- James W. Ellis, Disability Advocacy and Atkins, 57 DePaul Law Review 653, 657 (2008). ("In the eight decades since Buck, the Court has never overruled it.").

- Kaelber, Lutz. "Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States - Virginia". Lutz Kaelber, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Vermont. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- "Sexual Sterilization, Virginia Code §§ 54.1-2974 - 54.1-2980". General Assembly of Virginia. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- White, G. Edward, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: Law and the Inner Self, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 407.

- Galton, Francis (1883), Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development, London: Macmillan, p. 199

- Pandora's Lab: Seven stories of Science gone wrong

- "Buck vs. Bell Trial", Eugenics Archive, retrieved October 16, 2009

- "Chapter 46B of the Code of Virginia § 1095h–m (1924)". encyclopediavirginia.org. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "Online Services". Central Virginia Training Center. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved June 23, 2009. Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded

- "Buck v. Bell (1927)". encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "Buck, Carrie (1906–1983)". encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- Lombardo, Paul A. (1985), "Three Generations, No Imbeciles: New Light on Buck v. Bell", New York University Law Review, 60 (1): 30–62, PMID 11658945

- Cohen, Adam; Goodman, Amy; Shaikh, Nermeen, eds. (March 17, 2016). Buck v. Bell: Inside the SCOTUS Case That Led to Forced Sterilization of 70,000 & Inspired the Nazis. Democracy Now!. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016. Alt URL

- "Buck v. Bell: Inside the SCOTUS Case That Led to Forced Sterilization of 70,000 & Inspired the Nazis". Democracy Now!. March 17, 2016.

- Cohen, Adam (2016). Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck. New York, New York: Penguin Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1594204180.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (July 1984). "Carrie Buck's Daughter" (PDF). Natural History. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 21, 2015. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- Dorr, Gregory Michael. "Buck v. Bell (1927)". Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- Lombardo, Paul A. (2008). Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, The Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 190. ISBN 9780801890109. OCLC 195763255.

- Lombardo, Paul A. (2003). "Facing Carrie Buck". The Hastings Center Report. 33 (2): 14–17. doi:10.2307/3528148. ISSN 0093-0334. JSTOR 3528148. PMID 12760114 – via JSTOR.

- "Buck v. Bell: The Test Case for Virginia's Eugenical Sterilization Act". Eugenics: Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Virginia, Eugenics & Buck v. Bell. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- USA Today (November 16, 2008). "Re-examining Supreme Court support for sterilization". ABC News. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- "Bell, John H. (1883–1934)". encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "Eugenics: Eugenics in Virginia". Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Bruinius, Harry (2007). Better for All the World: The Secret History of Forced Sterilization and America's Quest for Racial Purity. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-375-71305-7.

- "Irving Whitehead, still image with audio". Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory DNA Learning Center. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- Fisher, Louis (2019). "Privacy Rights". Reconsidering Judicial Finality: Why the Supreme Court Is Not the Last Word on the Constitution. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 124. doi:10.2307/j.ctvqmp2sk. ISBN 978-0-7006-2810-0. JSTOR j.ctvqmp2sk. S2CID 241678748.

- The court's majority opinion states that the court accepted the diagnoses of the Virginia medical personnel, not looking into whether they were correct: "Carrie Buck is a feeble-minded white woman who was committed to the State Colony above mentioned in due form. She is the daughter of a feeble-minded mother in the same institution, and the mother of an illegitimate feeble-minded child." 274 U.S. at 205

- 274 U.S. 200 (Buck v. Bell) Archived 2011-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, Justia.com U.S. Supreme Court Center Archived 2021-05-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- 274 U.S. at 207.

- "BUCK v. BELL, Superintendent of State Colony Epileptics and Feeble Minded". Legal Information Institute.

The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U. S. 11, 25 S. Ct. 358, 49 L. Ed. 643, 3 Ann. Cas. 765. Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

- Phillip Thompson (February 23, 2005). "Silent Protest: A Catholic Justice Dissents in Buck V. Bell" (PDF). St. John's University. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2012. "Silent Protest: A Catholic Justice Dissents in Buck v. Bell"

- "The Eugenics Crusade". American Experience. PBS. 2018. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- Lombardo, Paul A. (2003). "Facing Carrie Buck". The Hastings Center Report. 33 (2): 16. doi:10.2307/3528148. ISSN 0093-0334. JSTOR 3528148. PMID 12760114 – via JSTOR.

- "Influence of Virginia's Eugenical Sterilization Act". Eugenics: Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Virginia, Eugenics & Buck v. Bell. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- Quinn, Peter (February/March 2003). "Race Cleansing in America Archived February 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine American Heritage. Retrieved 7-27-2010.

- Harrry Hamilton Laughlin (December 1922). "Model Eugenical Sterilization Law". Eugenical Sterilization in the United States. Psychopathic Laboratory of the Municipal Court of Chicago. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2005. Harvard website

- Bruinius, Harry (2007). Better for All the World: The Secret History of Forced Sterilization and America's Quest for Racial Purity. New York: Vintage Books. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-375-71305-7.

- "Sexual Sterilization, Virginia Code §§ 54.1-2974 - 54.1-2980". General Assembly of Virginia. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 154 (1973) ("The privacy right involved, therefore, cannot be said to be absolute. In fact, it is not clear to us that the claim asserted by some amici that one has an unlimited right to do with one's body as one pleases bears a close relationship to the right of privacy previously articulated in the Court's decisions. The Court has refused to recognize an unlimited right of this kind in the past.")

- Fieger v. Thomas, 74 F.3d 740, 750 (6th Cir. 1996) ("This claim of selective prosecution really amounts to a weak equal protection claim. And, as Justice Holmes pointed out in the only part of Buck v. Bell that remains unrepudiated, a claim of a violation of the Equal Protection Clause based upon selective enforcement 'is the usual last resort of constitutional arguments.").

- Vaughn v. Ruoff, 253 F.3d 1124, 1129 (8th Cir. 2001) ("It is true that involuntary sterilization is not always unconstitutional if it is a narrowly tailored means to achieve a compelling government interest. See Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200, 207–08, 47 S.Ct. 584, 71 L.Ed. 1000 (rejecting due process and equal protection challenges to compelled sterilization of mentally handicapped woman). It is also true that the mentally handicapped, depending on their circumstances, may be subjected to various degrees of government intrusion that would be unjustified if directed at other segments of society. See Cleburne, 473 U.S. at 442–47, 105 S.Ct. 3249; Buck, 274 U.S. at 207–08, 47 S.Ct. 584. It does not follow, however, that the State can dispense with procedural protections, coerce an individual into sterilization, and then after the fact argue that it was justified. If it did, it would invite conduct, like that alleged in this case, that is ripe for abuse and error.").

- Warden, Derek (2019). "Ex Tenebris Lux: Buck v. Bell and the Americans with Disabilities Act". University of Toledo Law Review. 51. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

Further reading

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Cohen, Adam (2016), Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck, Penguin, ISBN 978-1-59420-418-0.

- Cullen-DuPont, Kathryn. Encyclopedia of Women's History in America (Infobase Publishing, 2009) pp 37–38

- Breed, Allen G. (August 13, 2011). "Eugenics victim, son fighting together for justice". Winfall, North Carolina. Associated Press. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- Bruinius, Harry (2007). Better for All the World: The Secret History of Forced Sterilization and America's Quest for Racial Purity. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-375-71305-7.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. (1995), "Mr. Justice Holmes and Three Generations of Imbeciles", The Supreme Court Reborn: The Constitutional Revolution in the Age of Roosevelt, New York: Oxford, pp. 3–25, ISBN 978-0-19-511131-6.

- Lombardo, Paul (2008), Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell., Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 365, ISBN 978-0-8018-9010-9

- Smith, J. David. The Sterilization of Carrie Buck (New Horizon Press, 1989)

External links

- Text of Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927) is available from: CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Professor Thomas D. Russell

- An account of the case from the Dolan DNA Learning Center

- Buck v. Bell (Case File #31681), archives.gov

- "Eugenics." Archived April 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University of Virginia

- "Buck v. Bell (1927)" by N. Antonios and C. Raup at the Embryo Project Encyclopedia

- Buck v. Bell at Encyclopedia Virginia

- "Noah Feldman on 'Buck v. Bell'". Mahindra Humanities Center. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021 – via YouTube.