Brunei Malay

The Brunei Malay language (Malay: Bahasa Melayu Brunei Jawi: بهاس ملايو بروني) is the most widely spoken language in Brunei and a lingua franca in some parts of Sarawak and Sabah, such as Labuan, Limbang, Lawas, Sipitang and Papar.[2][3] Though Standard Malay is promoted as the official national language of Brunei, Brunei Malay is socially dominant and it is currently replacing the minority languages of Brunei,[4] including the Dusun and Tutong languages.[5] It is quite divergent from Standard Malay to the point where it is almost mutually unintelligible with it.

| Brunei Malay | |

|---|---|

| Bahasa Melayu Brunei | |

| بهاس ملايو بروني | |

| Native to | Brunei, Malaysia |

| Ethnicity | Bruneian Malay, Kedayan |

Native speakers | 320,000 (2013–2019)[1] |

Austronesian

| |

| Latin (Malay alphabet) Arabic (Jawi) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | kxd |

| Glottolog | brun1242 |

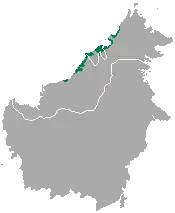

Area where Brunei Malay is spoken | |

Phonology

The consonantal inventory of Brunei Malay is shown below:[3][6]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | (ʔ) |

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | (f) | s | ʃ | (x) | h |

| voiced | (v) | (z) | ||||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Lateral | l | |||||

| Approximant | w | j | ||||

Notes:

- ^ /t/ is dental in many varieties of Malay, but it is alveolar in Brunei.[6]

- ^ /k/ is velar in initial position, but it is realised as uvular [q] in coda.[6]

- ^ Parenthesised sounds occur only in loanwords.

- All consonants can occur in word-initial position, except /h/. Therefore, Standard Malay hutan 'forest' became utan in Brunei Malay, and Standard Malay hitam 'black' became itam.[3]

- All consonants can occur in word-final position, except the palatals /tʃ, dʒ, ɲ/ and voiced plosives /b, d, ɡ/. Exceptions can be found in a few borrowed words such as mac 'March' and kabab 'kebab'.[2]

- ^ Some analysts exclude /w/ and /j/ from this table because they are 'margin high vowels',[7] while others include /w/ but exclude /j/.[2]

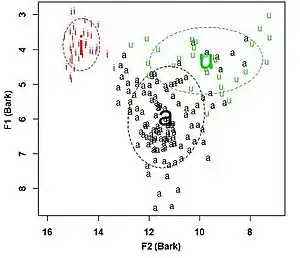

Brunei Malay has a three-vowel system: /i/, /a/, /u/.[2][8] Acoustic variation in the realisation of these vowels is shown in the plot on the right, based on the reading of a short text by a single female speaker.[3]

While /i/ is distinct from the other two vowels, there is substantial overlap between /a/ and /u/. This is partly because of the vowel in the first syllable of words such as maniup ('to blow') which can be realised as [ə]. Indeed, the Brunei Malay dictionary uses an 'e' for the prefix in this word, listing it as meniup,[9] though other analyses prefer to show prefixes such as this with 'a', on the basis that Brunei Malay just has three vowel phonemes.[10][7][2]

Language use

Brunei Malay, Kedayan and Kampong Ayer can be regarded as dialects of Malay. Brunei Malay is used by the numerically and politically dominant Brunei people, who traditionally lived on water, while Kedayan is used by the land-dwelling farmers, and the Kampong Ayer dialect is used by the inhabitants of the river north of the capital.[11][12] It has been estimated that 94% of the words of Brunei Malay and Kedayan are lexically related.[13]

Coluzzi studied the street signs in Bandar Seri Begawan, the capital city of Brunei Darussalam. The researcher concluded that except Chinese, "minority languages in Brunei have no visibility and play a very marginal role beyond the family and the small community."[14]

Vocabulary words

| Bruneian Malay | Peninsular Malaysia Malay

(Klang Valley standard) |

Meaning/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Aku/ku | First person singular | |

| Saya | ||

| Peramba | Patik | First person singular when in conversation with a Royal Family Member |

| Awak | Second person singular | |

| Kau | ||

| Ko | ||

| Awda | Anda | From (si) awang and (si) dayang. It is used like the Malay word anda. |

| Kamu | Second person plural | |

| Ia | Dia | Third person singular |

| Kitani | Kita | First person plural (inclusive) |

| Kita | To be used either like kitani or biskita | |

| Si awang | Beliau | Male third person singular |

| Si dayang | Female third person singular | |

| Biskita | Kita | To address a listener of older age. Also first person plural |

| Cinta | Tercinta | To address a loved one |

| Ani | Ini | This |

| Atu | Itu | That |

| (Di) mana? | Where (at)? | |

| Ke mana? | Where to? | |

| Lelaki | Male (human) | |

| Laki-laki | ||

| Perempuan | Female (human) | |

| Bini-bini[lower-alpha 1] | ||

| Budiman | Tuan/Encik | A gentleman |

| Kebawah Duli | Baginda | His Majesty |

| Awu | Yes | |

| Ya | ||

| Inda | No | |

| Tidak | ||

| kabat | Tutup | To close (a door, etc.) |

| Makan | To eat | |

| Suka | To like | |

| Cali | Lawak | Funny (adj.), derived from Charlie Chaplin |

| Siuk | Syok | cf. Malaysian syok, Singaporean shiok |

| Lakas | Lekas | To be quick, (in a) hurry(ing) (also an interjection) |

| Karang | Akan | At a later time, soon |

| Tarus | Terus | Straight ahead; immediately |

| Manada | Mana ada | Used as a term when in a state denial (as in 'No way!' or 'It can't be') |

| Baiktah | Lebih baik | 'Might as well ... ' |

| Orang putih | Orang putih; Mat salleh | Generally refers to a white Westerner. |

| Kaling | Refers to a Bruneian of Indian descent. (This is generally regarded as pejorative.)[15] | |

- In Malay, Bini-bini is exclusively used in Brunei to refer to a woman. In Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, it is an informal way to refer to one's wives or a group of married women.

Studies

The vocabulary of Brunei Malay has been collected and published by several western explorers in Borneo including Pigafetta in 1521, De Crespigny in 1872, Charles Hose in 1893, A. S. Haynes in 1900, Sidney H. Ray in 1913, H. B. Marshall in 1921, and G. T. MacBryan in 1922, and some Brunei Malay words are included in A Malay-English Dictionary by R. J. Wilkinson.[16][17][18]

The language planning of Brunei has been studied by some scholars.[19][20]

References

- Brunei Malay at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- Clynes, A. (2014). Brunei Malay: An Overview. In P. Sercombe, M. Boutin, & A. Clynes (Eds.), Advances in Research on Linguistic and Cultural Practices in Borneo (pp. 153–200). Phillips, ME: Borneo Research Council. Pre-publication draft available at http://fass.ubd.edu.bn/staff/docs/AC/Clynes-Brunei-Malay.pdf

- Deterding, David & Athirah, Ishamina. (2017). Brunei Malay. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 47(1), 99–108. doi:10.1017/S0025100316000189

- McLellan, J., Noor Azam Haji-Othman, & Deterding, D. (2016). The language situation in Brunei Darussalam. In Noor Azam Haji-Othman, J. McLellan, & D. Deterding (Eds.), The use and status of language in Brunei Darussalam: A kingdom of unexpected linguistic diversity (pp. 9–16). Singapore: Springer.

- Noor Azam Haji-Othman & Siti Ajeerah Najib (2016). The state of indigenous languages in Brunei. In Noor Azam Haji-Othman, J. McLellan, & D. Deterding (Eds.), The use and status of language in Brunei Darussalam: A kingdom of unexpected linguistic diversity (pp. 17–28). Singapore: Springer.

- Clynes, Adrian & Deterding, David. (2011). Standard Malay (Brunei). Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 41(2), 259–268. doi:10.1017/S002510031100017X

- Mataim Bakar. (2007). The phonotactics of Brunei Malay: An Optimality Theoretic account. Bandar Seri Begawan: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Brunei.

- Poedjosoedarmo, G. (1996). Variation and change in the sound systems of Brunei dialects of Malay. In P. Martin, C. Ozog, & Gloria Poedjosoedarmo (Eds.), Language use and language change in Brunei Darussalam (pp. 37–42). Athens, OH: Ohio University Center for International Studies.

- Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Brunei. (2007). Kamus Bahasa Melayu Brunei (Edisi Kedua) [Brunei Malay dictionary, 2nd edition]. Bandar Seri Begawan: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka Brunei.

- Jaludin Chuchu. (2000). Morphology of Brunei Malay. Bangi: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

- Gallop, 2006. "Brunei Darussalam: Language Situation". In Keith Brown, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- Wurm, Mühlhäusler, & Tryon, Atlas of languages of intercultural communication in the Pacific, Asia and the Americas, 1996:677

- Nothofer, B. (1991). The languages of Brunei Darussalam. In H. Steinhauer (Ed.), Papers in Austronesian Linguistics (pp. 151–172). Canberra: Australian National University.

- Coluzzi, Paolo. (2012). The Linguistic Landscape of Brunei Darussalam: Minority Languages and the Threshold of Literacy. South East Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 12, 1-16. Retrieved 14 April 2019 from http://fass.ubd.edu.bn/SEA/volume12.html

- Najib Noorashid (2016). The 'K' word referring to Indians in Brunei. Paper presented at the Brunei-Malaysia 2016 Forum, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, 16–17 November 2016.

- Martin, P. W. (1994). Lexicography in Brunei Darussalam: An overview. In B. Sibayan & L. E. Newell (Eds.), Papers from the First Asia International Lexicography Conference, Manila, Philippines, 1992. LSP Special Monograph Issue, 35 (pp. 59–68). Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines. Archived 2015-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Anton Abraham Cense; E.M. Uhlenbeck (2013). Critical Survey of Studies on the Languages of Borneo. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 8. ISBN 978-94-011-8925-5.

- Jatswan S. Sidhu (2009). Historical Dictionary of Brunei Darussalam. Scarecrow Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-8108-7078-9.

- Coluzzi, Paolo. (2011). Majority and minority language planning in Brunei Darussalam. Language Problems and Language Planning, 35(3), 222-240. doi:10.1075/lplp.35.3.02col

- Clynes, Adrian. (2012). Dominant language transfer in minority language documentation projects: Some examples from Brunei. Language Documentation & Conservation, 6, 253-267.

Further reading

- Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain) (1872). On Northern Borneo. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society XVI. Edward Stanford. pp. 171–187.

- Haynes, A. S. “A List of Brunei-Malay words.” JSBRAS 34 ( July 1900): 39—48.

- Hose, Charles. No. 3. "A Journey up the Baram River to Mount Dulit and the Highlands of Borneo". The Geographical Journal. No. 3. VOL. I. (March, 1893)

- MacBryan, G.T. 1922. Additions to a vocabulary of Brunei-Malay. JSBRAS. 86:376–377.

- Marshall, H.B. and Moulton, J.C. 1921, "A vocabulary of Brunei Malay", in Journal of the Straits Branch, Royal Asiatic Society.

- Marshall, H.B. 1921. A vocabulary of Brunei Malay. JSBRAS. 83:45–74.

- Ray, Sidney H. 1913. The Languages of Borneo. The Sarawak Museum Journal. 1,4:1–196.

- Roth, Henry Ling. 1896. The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. 2 vols. London: Truslove and Hanson. Rep. 1980. Malaysia: University of Malaya Press. VOL I. VOL II. VOL II.

- Marshall, H. B. (1921), "A Vocabulary of Brunei Malay", Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (83): 45–74, JSTOR 41561363

- Soderberg, Craig D. (2014). "Kedayan". Illustrations of the IPA. Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 44 (2): 201–205. doi:10.1017/S0025100314000061, with supplementary sound recordings.

- Deterding, David and Athirah, Ishamina (2017). "Brunei Malay". Illustrations of the IPA. Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 47 (1): 108–99. doi:10.1017/S0025100316000189

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), with supplementary sound recordings.