Bruce Castle

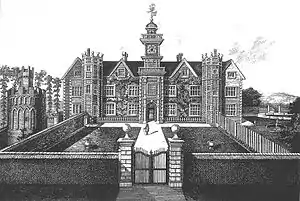

Bruce Castle (formerly the Lordship House) is a Grade I listed 16th-century[1] manor house in Lordship Lane, Tottenham, London. It is named after the House of Bruce who formerly owned the land on which it is built. Believed to stand on the site of an earlier building, about which little is known, the current house is one of the oldest surviving English brick houses. It was remodelled in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

The house has been home to Sir William Compton, the Barons Coleraine and Sir Rowland Hill, among others. After serving as a school during the 19th century, when a large extension was built to the west, it was converted into a museum exploring the history of the areas now constituting London Borough of Haringey and, on the strength of its connection with Sir Rowland Hill, the history of the Royal Mail. The building also houses the archives of the London Borough of Haringey. Since 1892 the grounds have been a public park, Tottenham's oldest.

Origins of the name

The name Bruce Castle is derived from the House of Bruce, who had historically owned a third of the manor of Tottenham. However, there was no castle in the area, and it is unlikely that the family lived nearby.[3] Upon his accession to the Scottish throne in 1306, Robert I of Scotland forfeited his lands in England, including the Bruce holdings in Tottenham,[3] ending the connection between the Bruce family and the area. The former Bruce land in Tottenham was granted to Richard Spigurnell and Thomas Hethe.[4]

The three parts of the manor of Tottenham were united in the early 15th century under the Gedeney family and have remained united since.[4] In all early records, the building is referred to as the Lordship House. The name Bruce Castle first appears to have been adopted by Henry Hare, 2nd Baron Coleraine (1635–1708),[3] although Daniel Lysons speculates in The Environs of London (1795) the name's use dates to the late 13th century.[4]

Architecture

A detached, cylindrical Tudor tower stands immediately to the south-west of the house, and is generally considered to be the earliest part of the building;[5] however, Lysons believes it to have been a later addition.[4] The tower is built of local red brick, and is 21 ft (6.4 m) tall, with walls 3 ft (0.91 m) thick.[5] In 2006, excavations revealed that it continues for some distance below the current ground level.[6] It was described in 1829 as being over a deep well, and being used as a dairy.[7]

Sources disagree on the house's initial construction date, and no records survive of its construction. There is some archaeological evidence dating parts of the building to the 15th century;[5] William Robinson's History and Antiquities of the Parish of Tottenham (1840) suggests a date of about 1514,[8] although the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments attributes it to the late 16th century. Nikolaus Pevsner speculates the front may have formed part of a courtyard house of which the remainder has disappeared.[9]

The Grade I mansion's principal façade has been substantially remodelled. The house is made of red brick with ashlar quoining and the principal façade, terminated by symmetrical matching bays, has tall paned windows. The house and detached tower are among the earliest uses of brick as the principal building material for an English house.[10]

Henry Hare, 2nd Baron Coleraine (1635–1708) oversaw a substantial remodelling of the house in 1684, and much of the existing south façade dates from that time. The end bays were heightened, and the central porch was rebuilt with stone quoins and pilasters, a balustraded top and a small tower and cupola.[9] A plan from 1684 shows the hall in the house's centre, with service rooms to the west and the main parlour to the east. On the first floor, the dining room was over the hall, the main bedchamber over the kitchen, and a lady's chamber over the porch.[9]

In the early 18th century Henry Hare, 3rd Baron Coleraine (1694–1749) oversaw a remodelling of the north of the house, that added a range of rooms to the north and the Coleraine coat of arms to the pediment of the north façade.[9] In the late 18th century, under the ownership of James Townsend, the narrow east façade of the house was remodelled into an entrance front, and given the appearance of a typical Georgian house. At the same time, the south front's gabled attics were removed, giving the house's southern elevation its current appearance.[9] An inventory of the house made in 1789 in preparation for its sale listed a hall, saloon, drawing room, dining room and breakfast parlour on the ground floor, with a library and billiard room on the first floor.[9]

In the early 19th century, the house's west wing was demolished, leaving it with the asymmetrical appearance it retains today.[11] The house was converted into a school, and in 1870 a three-story extension was built in the Gothic Revival style to the northwest of the house.[9]

The 2006 excavations by the Museum of London uncovered the chalk foundations of an earlier building on the site, of which nothing is known.[6] Court rolls of 1742 refer to the repair of a drawbridge, implying that the building then had a moat.[5] A 1911 archaeological journal made passing reference to "the recent levelling of the moat".[12]

Early residents

It is generally believed the house's first owner was Sir William Compton, Groom of the Stool to Henry VIII and one of the period's prominent courtiers, who acquired the manor of Tottenham in 1514.[5] However, there is no evidence of Compton's living in the house, and there is some evidence the building dates to a later period.[5]

The earliest known reference to the building dates from 1516, when Henry VIII met his sister Margaret, Queen of Scots, at "Maister Compton's House beside Tottenham".[8] The Comptons owned the building throughout the 16th century, but few records of the family or the building survive.[14]

In the early 17th century, Richard Sackville, 3rd Earl of Dorset and Lady Anne Clifford owned the house. Sackville ran up high debts through gambling and extravagant spending; the house (then still called "The Lordship House") was leased to Thomas Peniston. Peniston's wife, Martha, daughter of Sir Thomas Temple was said to be the Earl of Dorset's mistress.[15] The house was later sold to wealthy Norfolk landowner Hugh Hare.[16]

17th century: the Hare family

Hugh Hare, 1st Baron Coleraine

Hugh Hare (1606–1667) had inherited a large amount of money from his great-uncle Sir Nicholas Hare, Master of the Rolls. On the death of his father, his mother had remarried Henry Montagu, 1st Earl of Manchester, allowing the young Hugh Hare to rise rapidly in Court and social circles. He married Montagu's daughter by his first marriage and purchased the manor of Tottenham, including the Lordship House, in 1625, and was ennobled as Baron Coleraine shortly thereafter.[16]

As he was closely associated with the court of Charles I, Hare's fortunes went into decline during the English Civil War. His castle at Longford and his house in Totteridge were seized by Parliamentary forces, and returned upon the Restoration in a severe state of disrepair.[16] Records of Tottenham from the period are now lost, and the ownership and condition of the Lordship House during the Commonwealth of England are unknown.[16] Hugh Hare died at his home in Totteridge in 1667, having choked to death on a bone eating turkey while laughing and drinking,[16] and was succeeded by his son Henry Hare, 2nd Baron Coleraine.[17]

Henry Hare, 2nd Baron Coleraine

Henry Hare (1635–1708) settled at the Lordship House, renaming it Bruce Castle in honour of the area's historic connection with the House of Bruce.[3] Hare was a noted historian and author of the first history of Tottenham. He grew up at the Hare family house at Totteridge, and it is not known when he moved to Tottenham. At the time of the birth of his first child, Hugh, in 1668, the family were still living in Totteridge, while by the time of the death of his first wife Constantia, in 1680, the family were living in Bruce Castle. According to Hare, Constantia was buried in All Hallows Church in Tottenham. However, the parish register for the period is complete and makes no mention of her death or burial.[18]

Following the death of Constantia, Hare married Sarah Alston. They had been engaged in 1661, but she had instead married John Seymour, 4th Duke of Somerset. There is evidence that during Sarah's marriage to Seymour and Hare's marriage to Constantia, a close relationship was sustained between them.[19]

The house was substantially remodelled in 1684, following Henry Hare's marriage to the dowager Duchess of Somerset, and much of the existing south façade dates from this time.[9] The façade's central tower with a belvedere is a motif of the English Renaissance of the late 16th/early 17th centuries. Hatfield House, also close to London, had a similar central tower constructed in 1611, as does Blickling Hall in Norfolk, built circa 1616.

The Ghostly Lady of Bruce Castle

Although sources such as Pegram speculate that Constantia committed suicide in the face of a continued relationship between Hare and the Duchess of Somerset,[19] little is known about her life and the circumstances of her early death, and her ghost reputedly haunts the castle.[20]

The earliest recorded reference to the ghost appeared in 1858—almost two hundred years after her death—in the Tottenham & Edmonton Advertiser.

A lady of our acquaintance was introduced at a party to an Indian Officer who, hearing that she came from Tottenham, eagerly asked if she had seen the Ghostly Lady of Bruce Castle. Some years before he had been told the following story by a brother officer when encamped on a march in India. One of the Lords Coleraine had married a beautiful lady and while she was yet in her youth had been seized with a violent hatred against her—whether from jealousy or not is not known. He first confined her to the upper part of the house and subsequently still more closely to the little rooms of the clock turret. These rooms looked on the balconies: the lady one night succeeded in forcing her way out and flung herself with child in arms from the parapet. The wild despairing shriek aroused the household only to find her and her infant in death's clutches below. Every year as the fearful night comes round (it is in November) the wild form can be seen as she stood on the fatal parapet, and her despairing cry is heard floating away on the autumnal blast.[18][21]

The legend has now been largely forgotten, and there have been no reported sightings of the ghost in recent times.[20]

Residents in the 18th century

Sarah Hare died in 1692 and was buried in Westminster Abbey,[19] and Hare in 1708, to be succeeded by his grandson Henry Hare, 3rd Baron Coleraine. Henry Hare was a leading antiquary, residing only briefly at Bruce Castle between lengthy tours of Europe.

The house was remodelled again under the 3rd Baron Coleraine's ownership. An extra range of rooms was added to the north, and the pediment of the north front ornamented with a large coat of the Coleraine arms.[9]

Hare's marriage was not consummated, and following an affair with a French woman, Rosa du Plessis, du Plessis bore him his only child, a daughter named Henrietta Rosa Peregrina, born in France in 1745.[22] Hare died in 1749 leaving his estates to the four-year-old Henrietta, but her claim was rejected owing to her French nationality. After many years of legal challenges, the estates, including Bruce Castle, were granted to her husband James Townsend, whom she had married at age 18.[22]

James Townsend was a leading citizen of the day. He served as a magistrate, was Member of Parliament for West Looe, and in 1772 became Lord Mayor of London, while Henrietta was a prominent artist, many of whose engravings of 18th-century Tottenham survive in the Bruce Castle Museum.[22]

After 1764, under the ownership of James Townsend, the house was remodelled again. The narrow east front was remodelled into an entrance front, and given the appearance of a typical Georgian house, while the gabled attics on the south front were removed, giving the south façade the appearance it has today.[9]

James and Henrietta Townsend's son, Henry Hare Townsend, showed little interest in the area or in the traditional role of the Lord of the Manor. After leasing the house to a succession of tenants, the house and grounds were sold in 1792 to Thomas Smith of Gray's Inn as a country residence.[22]

John Eardley Wilmot

John Eardley Wilmot (c. 1749 – 23 June 1815) was Member of Parliament for Tiverton (1776–1784) and Coventry (1784–1796), and in 1783 led the Parliamentary Commission investigating the events that led to the American Revolution. He also led the processing of compensation claims, and the supply of basic housing and provisions, for the 60,000 Loyalist refugees who arrived in England after the independence of the United States.[11]

Following the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789, a second wave of refugees arrived in England. Although the British government did not offer them organised relief, Wilmot, in association with William Wilberforce, Edmund Burke and George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, 1st Marquess of Buckingham, founded "Wilmot's Committee", which raised funds to provide accommodation and food, and found employment for refugees from France, large numbers of whom settled in the Tottenham area.[11]

In 1804, Wilmot retired from public life and moved to Bruce Castle to write his memoirs of the American Revolution and his role in the investigations of its causes and consequences. They were published shortly before his death in 1815.[11] After Wilmot's death, London merchant John Ede purchased the house and its grounds, and demolished the building's west wing.[11]

The Hill School

Hill and his brothers had taken over the management of their father's school in Birmingham in 1819, which opened a branch at Bruce Castle in 1827, with Rowland Hill as Headmaster. The school was run along radical lines inspired by Hill's friends Thomas Paine, Richard Price and Joseph Priestley;[23] all teaching was on the principle that the teacher's role is to instill the desire to learn, not to impart facts, corporal punishment was abolished and alleged transgressions were tried by a court of pupils, while the school taught a radical (for the time) curriculum including foreign languages, science and engineering.[24][25] Among other pupils, the school taught the sons of many London-based diplomats, particularly from the newly independent nations of South America, and the sons of computing pioneer Charles Babbage.[24]

In 1839 Rowland Hill, who had written an influential proposal on postal reform, was appointed as head of the General Post Office (where he introduced the world's first postage stamps), leaving the school in the hands of his younger brother Arthur Hill.[24]

During the period of the School's operation, the character of the area had changed beyond recognition. Historically, Tottenham had consisted of four villages on Ermine Street (later the A10 road), surrounded by marshland and farmland.[26] The construction of the Northern and Eastern Railway in 1840, with stations at Tottenham Hale and Marsh Lane (later Northumberland Park), made commuting from Tottenham to central London feasible for the first time (albeit by a circuitous eight-mile route via Stratford, more than double the distance of the direct road route), as well as providing direct connections to the Port of London.[27] In 1872 the Great Eastern Railway opened a direct line from Enfield to Liverpool Street station,[28] including a station at Bruce Grove, close to Bruce Castle;[29] the railway provided subsidised workmen's fares to allow poor commuters to live in Tottenham and commute to work in central London.[30] As a major rail hub, Tottenham grew into a significant residential and industrial area; by the end of the 19th century, the only remaining undeveloped areas were the grounds of Bruce Castle itself, and the waterlogged floodplains of the River Lea at Tottenham Marshes and of the River Moselle at Broadwater Farm.[26]

In 1877 Birkbeck Hill retired from the post of headmaster, ending his family's association with the school. The school closed in 1891, and Tottenham Council purchased the house and grounds. The grounds of the house were opened to the public as Bruce Castle Park in June 1892,[31] the first public park in Tottenham.[32] The house opened to the public as Bruce Castle Museum in 1906.[33][34]

Heraud's Tottenham

Bruce Castle was among the buildings mentioned in John Abraham Heraud's 1820 Spenserian epic, Tottenham, a romantic depiction of the life of Robert the Bruce:[35]

Lovely is moonlight to the poet's eye,

That in a tide of beauty bathes the skies,

Filling the balmy air with purity,

Silent and lone, and on the greensward dies—

But when on ye her heavenly slumber lies,

TOWERS OF BRUS! 'tis more than lovely then.—

For such sublime associations rise,

That to young fancy's visionary ken,'Tis like a maniac's dream—fitful and still again.[36]

Present day

Bruce Castle is now a museum, holding the archives of the London Borough of Haringey, and housing a permanent exhibition on the past, present and future of Haringey and its predecessor boroughs, and temporary displays on the history of the area.[32] Other exhibits include an exhibition on Rowland Hill and postal history,[35] a significant collection of early photography, a collection of historic manorial documents and court rolls related to the area,[37] and one of the few copies available for public reading of the Spurs Opus, the complete history of Tottenham Hotspur.[38] In 1949, the building was Grade I listed;[39] the round tower was separately Grade I listed at the same time,[40] and the 17th-century southern and western boundary walls of the park were Grade II listed in 1974.[41][42] In 1969 the castle became home to the regimental museum of the Middlesex Regiment[43] whose collection was subsequently transferred to the National Army Museum.[44]

In July 2006 a major community archaeological dig was organised in the grounds by the Museum of London Archaeological Archive and Research Centre, as part of the centenary celebrations of the opening of Bruce Castle Museum,[6] in which large numbers of local youths took part.[45][46] As well as large quantities of discarded everyday objects, the chalk foundations of what appears to be an earlier house on the site were discovered.[6]

In 2012 the public grounds at Bruce Castle were used for PARK ART in Haringey, part of the borough's cultural Olympiad offer for 2012. Up Projects, in partnership with Haringey Council and funded by Arts Council England, commissioned Ben Long to create "Lion Scaffolding Sculpture",[47] a nine-metre tall classical lion on a plinth that was constructed from builder's scaffolding. The monumental sculpture, created for the front lawn of Bruce Castle Museum, referenced the traditional archetype of the regal lion commonly found in the grounds of stately homes, but also the heraldic emblem of Robert the Bruce, therefore reflecting on the heritage of the building. Built in situ over four weeks, the fabrication became a durational performance, highlighting the role that work and labour play in the development of any artistic or creative pursuit.[48][49]

Notes and references

- Sources differ as to the date of construction; some date the current building to the 15th century, but most agree that the house dates from the 16th century, although there is no consensus as to the exact date.

- As with most other English maps of the period, the map is aligned with south at the top (i.e. "upside down" when compared to modern maps). The alignment of streets in the area is preserved today; the road running east-west is the present-day Lordship Lane, and the road running north-south past the church is the present-day Church Lane; Bruce Grove does not yet exist, but its eventual route can be seen in the field boundaries running diagonally immediately south of the castle. The large field opposite the house (marked "Lease") is the northeast corner of the water-meadow, which became Broadwater Farm. The fields to the east of Church Lane are the present Bruce Castle Park, while those to the west surrounding the church now form part of Tottenham Cemetery.

- Pegram 1987, p. 2

- Lysons, Daniel (1795), "Tottenham", The Environs of London, London, 3: 517–557, archived from the original on 4 June 2011, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Pegram 1987, p. 3

- Bruce Castle Park community excavation, 2006, Museum of London, 2006, archived from the original on 14 June 2015, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Bruce Castle Archived 9 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Vol. 13, No. 350., (3 January 1829). Retrieved 27 January 2010

- Robinson 1840, p. 216

- Cherry and Pevsner 1998, p. 584

- Cherry and Pevsner 1998, p. 11

- Pegram 1987, p. 9

- Page, William (1911), "Ancient Earthworks", A History of the County of Middlesex, 2: 1–14, archived from the original on 5 December 2008, retrieved 2 October 2008

- An added inscription on this painting misidentifies the sitter as Edward Sackville, Richard's younger brother, later 4th Earl of Dorset. See Karen Hearn, ed. Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England 1530–1630. New York: Rizzoli, 1995. ISBN 0-8478-1940-X, pp. 198–199

- Pegram 1987, p. 4

- Clifford 1990, p. 83

- Pegram 1987, p. 5

- Cokayne, George E.; Howard de Walden, Thomas Evelyn Scott-Ellis, Baron; Warrand, Duncan; Gibbs, Vicary; Doubleday, H. Arthur; White, Geoffrey H. (1910). The complete peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom : extant, extinct, or dormant. Vol. 3: Canonteign to Cutts. London: St Catherine's Press. p. 366.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pegram 1987, p. 6

- Pegram 1987, p. 7

- Underwood 1992, pp. 46–147

- "The Ghostly Lady of Bruce Castle", Tottenham & Edmonton Advertiser (March 1858)

- Pegram 1987, p. 8

- Dick, Malcolm (2004), Joseph Priestley and his Influence on Education in Birmingham (65 KB

DOC), Revolutionary Players of Industry and Innovation, archived from the original on 1 April 2007, retrieved 16 March 2009

DOC), Revolutionary Players of Industry and Innovation, archived from the original on 1 April 2007, retrieved 16 March 2009 - Pegram 1987, p. 10

- A printing press designed by Rowland Hill and built by the school's pupils is on display at London's Science Museum. At this time, school curricula were almost always restricted to the classics; for a school to include engineering was almost unique.

- "Tottenham Growth after 1850", A History of the County of Middlesex, Victoria County History, 5: 317–324, 1976, archived from the original on 11 March 2007, retrieved 6 June 2007

- Lake 1945, pp. 12–13

- Lake 1945, p. 22

- Connor 2004, § 54

- Olsen 1976, p. 290

- Cherry and Pevsner 1998, p. 57

- Bruce Castle Museum, London Borough of Haringey, archived from the original on 24 April 2010, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Pegram 1987, p. 11

- Bruce Castle Museum, Haringey Council, archived from the original on 24 April 2010, retrieved 9 November 2014

- Haringey, Hidden London, archived from the original on 7 October 2008, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Heraud, John Abraham (1820), Tottenham: A Poem, archived from the original on 6 August 2017, retrieved 6 August 2017

- New Bruce Castle document sheds light on Tottenham history, London Borough of Haringey, 31 August 2007, archived from the original on 13 December 2009, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Fontaine, Valley (26 September 2008), "Spurs well and truly books, Bruce Castle Museum", BBC News, archived from the original on 14 November 2012, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Historic England, "Bruce Castle (1358861)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 23 March 2009

- Historic England, "Tower to the Southwest of Bruce Castle (1294388)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 23 March 2009

- Historic England, "Southern boundary wall to Bruce Castle Park (1079218)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 8 April 2009

- Historic England, "Wall along western boundary to grounds of Bruce Castle (1294666)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 8 April 2009

- "Tottenham: Manors", A History of the County of Middlesex, Victoria County History, 5: 324–330, 1976, archived from the original on 19 December 2013, retrieved 23 March 2009

- Middlesex Regiment Collection, Army Museums Ogilby Trust, archived from the original on 28 April 2009, retrieved 21 April 2009

- Financial statement, year ending 31 March 2007 (PDF), Museum of London, 4 October 2007, p. 17, archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2008, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Locals invited to muck in at Bruce Castle, Museum of London, 3 July 2006, archived from the original on 6 September 2008, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Alderson, Rob (16 August 2012). "Ben Long's brilliant scaffolding lion is mane attraction in London park". It's Nice That. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- "UP Projects". Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- Nott, George (20 July 2012). "Sculptor Ben Long on creating huge animal sculptures – from scaffolding poles". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Bibliography

- Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1998), The Buildings of England, vol. London 4: North, London: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-071049-3, OCLC 40453938

- Clifford, Anne (1990), The Diaries of Lady Anne Clifford, Stroud: Alan Sutton, ISBN 0-86299-560-4, OCLC 59978239

- Connor, Jim (2004), Branch Lines to Enfield Town and Palace Gates, Midhurst: Middleton Press, ISBN 1-904474-32-2, archived from the original on 29 September 2008, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Lake, G.H. (1945), The Railways of Tottenham, London: Greenlake Publications Ltd, ISBN 1-899890-26-2

- Olsen, Donald J (1976), The Growth of Victorian London, London: Batsford, ISBN 0-7134-3229-2, OCLC 185749148

- Pegram, Jean (1987), From Manor House... to Museum, Haringey History Bulletin, vol. 28, London: Hornsey Historical Society, ISBN 0-903481-05-7

- Robinson, William (1840), History and Antiquities of the Parish of Tottenham (2 ed.), London, OCLC 78467199

- Underwood, Peter (1992), The A–Z of British Ghosts, London: Chancellor Press, ISBN 1-85152-194-1