Bothriolepis

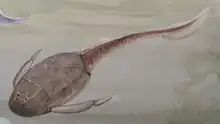

Bothriolepis (from Greek: βόθρος bóthros, 'trench' and Greek: λεπίς lepis 'scale') was a widespread, abundant and diverse genus of antiarch placoderms that lived during the Middle to Late Devonian period of the Paleozoic Era. Historically, Bothriolepis resided in an array of paleo-environments spread across every paleocontinent, including near shore marine and freshwater settings.[1] Most species of Bothriolepis were characterized as relatively small, benthic, freshwater detritivores (organisms that obtain nutrients by consuming decomposing plant/animal material), averaging around 30 centimetres (12 in) in length.[2] However, the largest species, B. rex, had an estimated bodylength of 170 centimetres (67 in). Although expansive with over 60 species found worldwide,[3] comparatively Bothriolepis is not unusually more diverse than most modern bottom dwelling species around today.[4]

| Bothriolepis Temporal range: Late Devonian ~ | |

|---|---|

| |

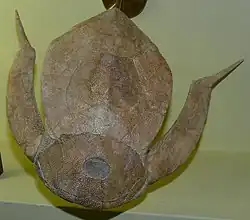

| Model of B. canadensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | †Placodermi |

| Order: | †Antiarchi |

| Family: | †Bothriolepididae |

| Genus: | †Bothriolepis Eichwald, 1840 |

| Species | |

| |

Classification

Bothriolepis is a genus placed within the placoderm order Antiarchi. The earliest antiarch placoderms first appeared in the Silurian period of the Paleozoic Era and could be found distributed on every paleocontinent by the Devonian period.[5] The earliest members of Bothriolepis appear by the Middle Devonian. Antiarchs, as well as other placoderms, are morphologically diverse and are characterized by bony plates that cover their head and the anterior part of the trunk.[5] Early ontogenetic stages of placoderms had thinner bony plates within both the head and trunk-shield, which allowed for easy distinction between early placoderm ontogenetic stages within the fossil record and taxa that possessed fully developed bony plates but were small by characterization.[5] Placoderm bony plates were generally made up of three layers, including a compact basal lamellar bony layer, a middle spongy bony layer and a superficial layer;[5] Bothriolepis can be classified as a placoderm since it possesses these layers. Placoderms were extinct by the end of the Devonian.[5] Placodermi is a paraphyletic group of the clade Gnathostomata, which includes all jawed vertebrates.[5] It is unclear exactly when gnathostomes emerged, but the scant early fossil record indicates that it was sometime in the Early Palaeozoic era.[6] The last species of Bothriolepis died out, together with the rest of Placodermi, at the end of the Devonian period.

General anatomy

Head

There are two openings through the head of Bothriolepis: a keyhole opening along the midline on the upper side for the eyes and nostrils and an opening for the mouth on the lower side near the anterior end of the head. A discovery regarding preserved structures that appear to be nasal capsules confirms the belief that the external nasal openings lay on the dorsal side of the head near the eyes.[7] Additionally, the position of the mouth on the ventral side of the skull is consistent with the typical horizontal resting orientation of Bothriolepis. It had a special feature on its skull, a separate partition of bone below the opening for the eyes and nostrils enclosing the nasal capsules called a preorbital recess.

Jaw

A new sample from the Gogo Formation in the Canning Basin of Western Australia has provided evidence regarding the morphological features of the visceral jaw elements of Bothriolepis. Using the sample, it is evident that the mental plate (a dermal bone that forms the upper part of the jaw) of antiarchs is homologous with the suborbital plate found in other placoderms. The lower jawbone consists of a differentiated blade and biting portions. Next to the mandibular joint are the prelateral and infraprelateral plates, which both are canal-bearing bones. The palatoquadrate lacks a high orbital process and was attached only to the ventral part of the mental plate, proving that the ethmoidal region of the braincase (the region of the skull that separates the brain and nasal cavity) was in fact deeper than originally believed.[8] In addition to the above-listed sample from the Gogo Formation, several other specimens have been found with mouthparts held in the natural position by a membrane that covers the oral region and attaches to the lateral and anterior margins of the head.[9] Bothriolepis has a jaw in which the two halves are separate and in the adult are functionally independent.[9]

Trunk

Bothriolepis had a slender trunk that was likely covered in soft skin with no scales or markings. The orientation that appears to have been mostly stable for resting was the dorsal surface up, evidenced by the flat surface on the ventral side.[1] The trunk's outline suggests that there may have been a notochord present surrounded by a membranous sheath,[9] however, there is no direct evidence of this since the notochord is made up of soft tissue, which is not typically preserved in the fossil record. Similar to other antiarchs, the thoracic shield of Bothriolepis was attached to its heavily armored head. Its box-like body was enclosed in armor plates, providing protection from predators. Attached to the ventral surface of the trunk is a large, thin, circular plate marked by deep-lying lines and superficial ridges. This plate lies just below the opening to the cloaca.[9]

Dermal skeleton

The dermal skeleton is organized in three layers: a superficial lamellar layer, a cancellous spongiosa, and a compact basal lamellar layer. Even in early ontogeny, these layers are apparent in specimen of Bothriolepis canadensis. The compact layers develop first.[10] The superficial layer is speculated to have denticles that may have been made of cellular bone.[11]

Fins and tail

Bothriolepis had a long pair of spine-like pectoral fins, jointed at the base, and again a little more than halfway along. These spike-like fins were probably used to lift the body clear off the bottom; its heavy armor would have made it sink quickly as soon as it lost forward momentum.[2][12] It may also have used its pectoral fins to throw sediment (mud, sand or otherwise) over itself. In addition to the pectoral fins, it also had two dorsal fins: a low, elongated anterior dorsal fin and a high rounded posterior dorsal fin [9]—though the hypothesized structure of the dorsal fins varies based on the specific species of Bothriolepis and has been modified several times in the reconstructions released by researchers as new information has become available. The caudal tail was elongated, ending in a narrow band, but is unfortunately rarely preserved in fossils.[9] Although there is no agreed-upon explanation of their function, Bothriolepis also had two membranous, ventral frills located on the posterior end of the trunk carapace on either side of the tail that each has two distinct regions.[7] There is no evidence that the frills were involved in support of the skeleton but it is possible that they either functioned as fins or were involved in reproduction, and may have even been present in one sex but not the other.[7]

Soft anatomy

Structures composed of soft tissue are typically not preserved in fossils because they break down easily and decompose much faster than hard tissues, meaning that the fossil record often lacks information regarding the internal anatomy of fossil species. Preservation of soft tissue structures can sometimes occur, however, if sediments fill the internal structures of an organism upon or after its death. Robert Denison's paper titled "The Soft Anatomy of Bothriolepis" explores the forms and organs of Bothriolepis.[7] These internal structures were preserved when different types of sediments surrounding the exterior of the animal-filled the internal carapaces (only organs that communicate with the exterior could be preserved in this manner). Three different sediment types were identified within the different sections of Bothriolepis: the first a pale greenish-gray medium-textured sandstone largely consisting of calcite; the second similar but finer sediment which preserves many of the organ forms; and the third distinct, fine-grained siltstone consisting of quartz, mica and other minerals but no calcite.[7] These sediments helped preserve the following internal elements:

Alimentary system

In general, the alimentary system of Bothriolepis –which includes the organs involved in ingestion, digestion, and removal of waste– can be described as simple and straight, unlike that of humans. It begins at the anterior end of the organism with a small mouth cavity located over the posterior area of the upper jaw plates. Posteriorly from the mouth, the alimentary system extends into a wider and dorso-ventrally flattened region called the pharynx, from which both the gills and lungs arise. The esophagus, which is also characterized as a dorso-ventrally flattened tube, extends from the mouth into the stomach and leads to a flattened ellipsoidal structure. This structure may be homologous to the anterior end of the intestine found in other fish.[7] The flatness of these structures may have been exaggerated when the fossil specimens experienced tectonic deformation through geologic time. The intestine begins narrowly on the anterior end, expands transversely, and then again narrows posteriorly towards the cylindrical rectum, which terminates just within the posterior end of the trunk carapace. While the alimentary system is primitive in nature and lacks an expanded stomach region, it is specialized by an independently acquired complex spiral valve, comparable to that in elasmobranchs and many bony fish and similar to that found in some sharks. A single fold of tissue rolled upon its own axis forms this specialized spiral valve.[7]

Gills

It is inferred that the gills of Bothriolepis are of the primitive type, though their structure is still not well understood. Laterally, they are enclosed by an opercular fold and are found in the space beneath the lateral part of the head shield, extending medially underneath the neurocranium. Compared to the gills of normally-shaped fish, the gill region of Bothriolepis is considered to be placed more dorsally, is anteriorly more crowded, and in general is relatively short and broad.[7]

Paired ventral sacs

Extending posteriorly from the trunk carapace are paired ventral sacs that extend to the anterior end of the spiral intestine. The sacs seem to originate at the pharynx as a single median tube, which then broadens posteriorly and eventually splits into two sacs that may be homologous to the lungs of certain dipnoans and tetrapods.[7] It has been hypothesized that these lungs, coupled with the jointed arms and rigid, supportive skeleton, would have allowed Bothriolepis to travel on land. Additionally, as Robert Denison[7] states because there is no evidence of a connection between the external naris and mouth, Bothriolepis likely breathed similarly to present-day lungfish, i.e., by placing the mouth above the water's surface and swallowing air.

Despite the original interpretation presented by Denison in 1941, not all paleontologists agree that placoderms like Bothriolepis actually possessed lungs. For example, in his paper "Lungs" in Placoderms, a Persistent Palaeobiological Myth Related to Environmental Preconceived Interpretations, D. Goujet suggests that although traces of some digestive organs may be apparent from the sedimentary structures, there is no evidence supporting the presence of lungs in the samples from the Escuminac formation of Canada upon which the original assertion was based. He notes that the worldwide distribution of Bothriolepis is restricted to strictly marine environments, and thus believes that the presence of lungs in Bothriolepis is uncertain. Further investigation of the fossils is likely necessary to reach a conclusion about the presence of lungs in Bothriolepis.[13]

Feeding

Bothriolepis, as with all other antiarchs, are thought to have fed by directly swallowing mouthfuls of mud and other soft sediments in order to digest detritus, small or microorganisms, algae, and other forms of organic matter in the swallowed sediments. Additionally, the positioning of the mouth on the ventral side of its head further suggests that Bothriolepis was likely a bottom-feeder. The regular presence of "carbonaceous material in the alimentary tract" is believed to indicate that most of its diet consisted of plant material.[7]

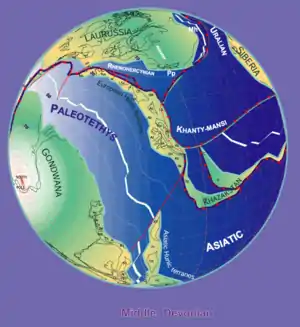

Distribution

By Stampfli & Borel, 2000

Bothriolepis fossils are found in Middle and Late Devonian strata (from 387 to 360 million years ago).[12] Because the fossils are found in freshwater sediments, Bothriolepis is presumed to have spent most of its life in freshwater rivers and lakes, but was probably able to enter salt water as well, because its range appeared to have corresponded with the Devonian continental coastlines. Large groupings of Bothriolepis specimens have been found in Asia, Europe, Australia (Gogo Formation and Mandagery Sandstone),[9][14] Africa (Waterloo Farm lagerstätte)[15] Pennsylvania (Catskill Formation),[1] Quebec (Escuminac Formation),[1] Virginia (Chemung),[16] Colorado,[16] Cuche Formation (Boyacá, Colombia),[17] and all around the world.

Catskill Formation site

The Catskill Formation (Upper Devonian, Famennian Stage), located in Tioga County, Pennsylvania, is the site of a large sample of small individuals of Bothriolepis. The sample was collected from a series of rock slabs that consisted of partial or complete, articulated, external skeletons. More than two hundred individuals were found packed closely together with little to no overlap. From this sample, much information regarding characteristics of juvenile Bothriolepis can be determined. A morphometric study performed by Jason Downs and co-authors highlights certain characteristics that indicate juvenility in Bothriolepis, including a moderately large head and moderately large orbital fenestra—both of which are characteristics also recognized by Erik Stensio in 1948 in the smallest B. canadensis individuals.[1] Several other features that Stensio marked indicative of young individuals can also be seen exhibited in the Catskill sample. These features include "delicate dermal bones with ornament consisting of continuous anastomosing ridges rather than tubercles, a dorsal trunk shield narrower than long and with a continuous and pronounced dorsal median ridge, and a pre-median plate that is wider than it is long".[1] B. nitida and B. minor are also described from this site.[18]

Species

Vertebrate paleontology is heavily dependent on the ability to differentiate between different species in a way that is consistent both within a particular genus and across all organisms. The genus Bothriolepis is no exception to this principle. Listed below are a few of the notable species within Bothriolepis; more than sixty species have been named in total, and it is likely that a sizeable proportion of them are valid due to the cosmopolitan nature of Bothriolepis.[3]

Bothriolepis canadensis

Bothriolepis canadensis is a taxon that often serves as a model organism for the order Antiarchi because of its enormous sample of complete, intact specimens found at the Escuminac Formation in Quebec, Canada.[1] Because of the vast sample size, this species is often used to compare growth data of newly acquired specimens of Bothriolepis, including those found in the Catskill Formation mentioned above. This comparison allows researchers to determine if newly found samples represent juvenile individuals or new "Bothriolepis" species.

B. canadensis was first described in 1880 by J.F. Whiteaves, using a limited number of disfigured samples. The next to propose a reconstruction of the species was W. Patten, who published his findings in 1904 after a discovery of several specimens that were well preserved in 3-D. In 1948, E. Stensio released a detailed depiction of B. canadensis anatomy using an abundance of material, which eventually became the most widely accepted description of this species. Since Stensio's publication, many others have provided reconstructed models of B. canadensis with modified aspects of the anatomy, including Vezina's modified single dorsal fin and more recently, reconstructions by Arsenault et al from specimens with little taphonomic distortion. Presently, the model of Arsenault et al. is regarded to be the most accurate, while there is still much debate about various aspects of this species' external anatomy. Despite the uncertainty, B. canadensis is still classically considered one of the most well-known species.[19]

The external skeleton of Bothriolepis canadensis is made of cellular dermal bone tissue and is characterized by distinct horizontal zonation or stratification.[10] The model fish has an average total length of 43.67 centimetres (17.19 in) and an average dermal armor length of 15.53 centimetres (6.11 in), which accounts for 35.6% of the estimated total length.[19] Like many antiarchs, B. canadensis also had narrow pectoral fins, a heterocercal caudal fin (meaning the notochord extends into the upper lobe of the caudal tail) and a large dorsal fin which likely didn't play an important role in propulsion but instead acted more as a stabilizer.[19]

Bothriolepis africana

Bothriolepis africana[15] is the Bothriolepis species known from the highest paleolatitude, being described from deposits originally laid down within the Late Devonian Antarctic circle. Remains have exclusively been recovered from a single carbonaceous shale near the top of the Late Devonian, Famennian, Witpoort Formation (Witteberg Group) exposed in a road cutting south of Makhanda/Grahamstown in South Africa. This site, the Waterloo Farm lagerstätte is interpreted as representing a back barrier coastal lagoonal setting with both marine and fluvial influences.[20] Gess observed that Bothriolepis was less abundant at the Waterloo Farm site than at most Bothriolepis-bearing localities, though a full ontogenetic series is represented. The head and trunk armour lengths ranged between 20–300 millimetres (0.79–11.81 in) which translates, based on the proportions of two of the smallest individuals (in which tail impressions are preserved) into full body lengths varying between 52–780 millimetres (2.0–30.7 in).[21] According to original description, Bothriolepis africana was considered to be most closely similar to Bothriolepis barretti[22] from the late Givetian of Antarctica. The similarities between the two have been used to suggest derivation of Bothriolepis africana from an East Gondwanan environment.[15]

Bothriolepis coloradensis

First described by Eastman in 1904, this species was found localized in present-day Colorado. There is a possibility that this species is similar, if not identical, to B. nitida, however because the material available regarding B. coloradensis is fragmented, it is impossible to compare the two species with any degree of certainty.[16]

Bothriolepis nitida

This species, found in present-day Pennsylvania, was originally described by J. Leidy in 1856. As mentioned above, there is much debate regarding the distinguishability between B. nitida and B. virginiensis, however based on evidence presented by Weems (2004),[16] there are several distinguishable traits specific to each species. B. nitida has a maximum headshield length of 65 millimetres (2.6 in), a narrow and shallow trifid preorbital recess, has an anterior-median-dorsal (AMD) plate that is wider than it is long and a ventral thoracic shield that has convex lateral borders.[16]

Bothriolepis rex

Originally described by Downs et al. (2016), Bothriolepis rex is from the Nordstrand Point Formation of Ellesmere Island, Canada. B. rex's body length is estimated at 1.7 metres (5.6 ft) and is, therefore, the largest known species of Bothriolepis. Its armor is especially thick and dense even when taking its size into account. Downs et al. (2016) suggest that this may have both protected the animal from large predators and served as ballast to prevent this large bottom-dweller from floating to the surface.

Bothriolepis virginiensis

Originally described by Weems et al. in 1981, this species, Bothriolepis virginiensis, is from the "Chemung", near Winchester, Virginia. Several traits found in B. virginiensis can also be found in other species of Bothriolepis, (especially B. nitida), including posterior oblique cephalic sensory line grooves that meet relatively far anteriorly on the nuchal plate, relatively elongated orbital fenestra and a low anterior-median-dorsal crest.[16] Characteristics that distinguish B. virginiensis from other species include but are not limited to fused head sutures, fused elements in adult distal pectoral fin segments and long premedian plate relative to headshield length.[16]

Currently, there is much debate regarding whether the species B. virginiensis and B. nitida can actually be distinguished from one another. Thomson and Thomas state that five species of Bothriolepis from the United States (B. nitida, B. minor, B. virginiensis, B. darbiensis and B. coloradensis) are unable to be consistently distinguished from one another.[4] Conversely, Weems asserts that there are several traits that distinguish the species from one another, including several listed above.[16]

Bothriolepis yeungae

This species is described in 1998, from Mandagery Sandstone in Canowindra, where is known from high numbers of placoderm specimens gathered at one place. Bothriolepis is one of the most common fish in Canowindra site alongside Remigolepis, over 1,300 individuals are discovered by 1998. This species is differed from all other species by having a reduced anterior process of the submarginal, separated from the posterior process of the submarginal by a wide, open notch. The head and trunk armour lengths ranged between 77.6–190 millimetres (3.06–7.48 in).[14]

References

- Downs, J.P.; Criswell, K.E.; Daeschler, E.B. (October 2011). "Mass mortality of juvenile antiarchs (Bothriolepis sp.) from the Catskill Formation (Upper Devonian, Famennian Stage), Tioga County, Pennsylvania". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 161 (161): 191–203. doi:10.1635/053.161.0111. S2CID 129501544.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- Young, G.C. (2010). "Placoderms (Armored Fish): Dominant Vertebrates of the Devonian Period". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 38: 523–550. Bibcode:2010AREPS..38..523Y. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-040809-152507. S2CID 86268051.

- Thomson, K.S.; Thomas, B. (August 2001). "On the status of species Bothriolepis (Placodermi, Antiarchi) in North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (4): 679–686. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0679:otsoso]2.0.co;2. S2CID 86104844.

- Johanson, Zerina; Trinajstic, Kate (2014). "Fossilized ontogenies: the contribution of placoderm ontogeny to our understanding of the evolution of early gnathostomes". Palaeontology. 57 (3): 505–516. doi:10.1111/pala.12093. S2CID 85673117.

- Brazeau, M. (2009). "The braincase and jaws of a Devonian 'acanthodian' and modern gnathostome origins" (PDF). Nature. 457 (7227): 305–308. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..305B. doi:10.1038/nature07436. hdl:10044/1/17971. PMID 19148098. S2CID 4321057.

- Denison, R.H. (September 1941). "The soft anatomy of Bothriolepis". Journal of Paleontology. 15 (5): 553–561.

- Young, G.C. (1984). "Reconstruction of the jaws and braincase in the Devonian placoderm Fish Bothriolepis". Palaeontology. 27 (3): 635–661.

- Patten, W. (July 1904). "New facts concerning Bothriolepis". Biological Bulletin. 7 (2): 113–124. doi:10.2307/1535537. JSTOR 1535537.

- Downs, J.P.; Donoghue, P.C.J. (2009). "Skeletal histology of Bothriolepis canadensis (Placodermi, Antiarchi) and evolution of the skeleton at the origin of jawed vertebrates". Journal of Morphology. 270 (11): 1364–1380. doi:10.1002/jmor.10765. PMID 19533688. S2CID 31585571.

- Giles, S. (2013). "Histology of "placoderm" dermal skeletons: implications for the nature of the ancestral gnathostome". Journal of Morphology. 274 (6): 627–644. doi:10.1002/jmor.20119. PMC 5176033. PMID 23378262.

- "Age of Fishes Museum - Fossils". Age of Fishes Museum, New South Wales, Australia.

- Goujet, D. (2011). ""Lungs" in placoderms, a persistent palaeobiological myth related to environmental preconceived interpretations". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 10 (5–6): 323–329. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2011.03.008.

- Johanson, Zerina (1998-11-25). "The Upper Devonian fish Bothriolepis (Placodermi: Antiarchi) from near Canowindra, New South Wales, Australia". Records of the Australian Museum. 50 (3): 315–348. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.50.1998.1289. ISSN 0067-1975.

- LONG, J. A. ,ANDERSON, M. E. ,GESS, R. W.&HILLER, N.(1997).New placoderm fishes from the Late Devonian of South Africa. Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology 17,253–268.

- Weems, R.E. (March 2004). "Bothriolepis viginiensis, a valid species of placoderm fish separable from Bothriolepis nitida". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (1): 245–250. doi:10.1671/20. S2CID 85572685.

- Janvier, Philippe; Villarroel A, Carlos (1998). "Los Peces Devónicos del Macizo de Floresta (Boyacá, Colombia). Consideraciones taxonómicas, bioestratigráficas, biogeográficas y ambientales". Geología Colombiana. 23: 3–18. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- Sallan, Lauren Cole; Coates, Michael I. (2010). "End-Devonian extinction and a bottleneck in the early evolution of modern jawed vertebrates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (22): 10131–10135. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914000107. ISSN 0027-8424.

- Bechard, I.; Arsenault, F.; Cloutier, R.; Kerr, J. (2014). "The Devonian fish Bothriolepis canadensis revisited with three-dimensional digital imagery". Palaeontologia Electronica. 17 (1).

- Gess, Robert W.; Whitfield, Alan K. (14 February 2020). "Estuarine fish and tetrapod evolution: insights from a Late Devonian (Famennian) Gondwanan estuarine lake and a southern African Holocene equivalent". Biological Reviews. doi:10.1111/brv.12590. PMID 32059074

- GESS,R.W.(2011).High latitude Gondwanan Famennian biodiversity patterns –Evidence from the South African Witpoort formation(Cape Supergroup,WittebergGroup).PhD thesis:University of the Witwatersrand, Johanneburg.

- YOUNG, G.(1984). Reconstruction of the jaws and braincase in the Devonian placoderm fish Bothriolepis. Palaeontology 27, 635–661.