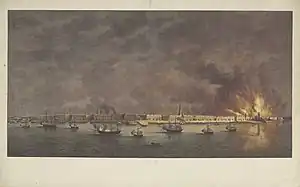

Bombardment of Antwerp (1830)

The Bombardment of Antwerp in 1830 was a military event that took place during the Belgian Revolution.

| Burning of Antwerp | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Belgian Revolution | |||||||

Bombardment of Antwerp, 1830 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Mostly Gunboats | Population was 73,605[1][2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Low, or none |

Estimated 9 Million Dollars+ of Property Destroyed [3] number of dead unknown but Chasse said blooday, and so many dead[4] | ||||||

Background

Antwerp joined the uprising in October. Dutch naval ships were subsequently sent to the river Scheldt, where they inspected all vessels for contraband. This led to a tightening of trade in the port city. As the navigation on the Scheldt fell under the control of the North Dutch navy, Antwerp lost its free access to the North Sea. Meanwhile, the royal troops, under the command of General David Hendrik Chassé, took refuge in the citadel in the southern part of Antwerp, a powerful stronghold from which they could bombard the city.[5] When General David Hendrik Baron Chassé received information that some Belgians had occupied Dutch posts within the city, and there where even reports of certain Belgians urging the Dutch forces to surrender the citadel. In response to these developments, Chassé took decisive action and ordered the bombardment of the city.[6]

Bombardment

During the intense conflict, the Belgians retaliated by firing upon the Dutch forces from the fortress and their ships, however the Dutch where unamused and kept bombarding the city resulting in numerous buildings catching fire and causing significant damage throughout the city. Witnesses from Brussels, who arrived in Antwerp, expressed their observations, describing a scene of chaos, with streets filled with debris and houses left in ruins, and called the Dutch people full with vengeance, and cruel. Emotions ran high, and many Belgians became even more resentful and angry towards the Dutch. Amid the turmoil, many

%252C_RP-P-OB-88.289.jpg.webp)

civilians were forced to flee the city, seeking safety while dealing with distress and grief. The Dutch forces were now attacking from multiple directions, and in return, the Belgians sent out fire ships to engage the Dutch. However, it seemed the Dutch forces were again unamused, and remained focused on their objective to inflict damage upon Antwerp and subject it to continuous bombardment.

After the bombardment, General Chassé perceived that his mission had been successfully accomplished.[7]

References

- Baedeker, Karl (1891). Belgium and Holland Handbook for Travellers (1891 ed.). Baedeker. p. 139.

- The Company in Law and Practice: Did Size Matter? (Middle Ages-Nineteenth Century) (E-boek ed.). Brill. pp. 170–172.

- Marsh, John (1831). New England Anti-Masonic Almanac for the Year of Our Lord 1832. John Marsh & Company. p. 29.

- Het bombardement van Antwerpen: lauwerkrans voor den luitenant-generaal baron Chassé gevlochten. p. 6.

- "Waarom ging Van Speijk liever de lucht in?". geschiedenismagazine (in Dutch).

- Carpenter, William; Hone, William (1831). Political Letters and Pamphlets Published for the Avowed Purpose of Trying with the Government the Question of Law--whether All Publications Containing News Or Intelligence, However Limited in Quantity Or Irregularly Issued, are Liable to the Imposition of the Stamp Duty of Fourpence, &c. : with a Full Report of the Editor's Trial and Conviction in the Court of Exchequer, at Westminster · Nummers 1-34. William Carpenter. p. 8.

- Carpenter, William; Hone, William (1831). Political Letters and Pamphlets Published for the Avowed Purpose of Trying with the Government the Question of Law--whether All Publications Containing News Or Intelligence, However Limited in Quantity Or Irregularly Issued, are Liable to the Imposition of the Stamp Duty of Fourpence, &c. : with a Full Report of the Editor's Trial and Conviction in the Court of Exchequer, at Westminster · Nummers 1-34. William Carpenter. p. 8.