Bolton Artillery

The Bolton Artillery, under various titles, has been a Volunteer unit of the British Army based in Bolton, Lancashire, since 1889. In the First World War it served in Egypt and Gallipoli in 1915–17, and then on the Western Front for the rest of the war, including Passchendaele, the German Spring Offensive and the Allied Hundred Days Offensive. Just before the outbreak of the Second World War the regiment formed a duplicate unit. The parent regiment served in the Battle of France and was evacuated from Dunkirk. Both regiments served at the Battle of Alamein and in the Italian campaign, while one of the regiments was involved in the intervention in Yugoslavia. The regiment was reformed postwar, and after a number of mergers its successors continue to serve in today's Army Reserve.

| 9th Lancashire Artillery Volunteers III East Lancashire Brigade (The Bolton Artillery), RFA 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment, RA 253 (Bolton) Field Regiment, RA 216 (Bolton Artillery) Battery, RA | |

|---|---|

Waistbelt of the Lancashire Volunteer Artillery, post-1891 | |

| Active | 1889–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Role | Position artillery Field artillery |

| Part of | 42nd (East Lancashire) Division |

| Garrison/HQ | Silverwell Street, Bolton |

| Engagements | |

Volunteer Force

The 9th Lancashire Artillery Volunteers was raised in 1889 from Bolton personnel serving with the Blackburn-based 3rd Lancashire Artillery Volunteers. (In 1863 the 3rd Lancashire AV had absorbed an earlier 9th Lancashire AV raised at Kirkdale and the 18th Lancashire AV originally raised at Great Lever but which had relocated to Bolton).[1][2][3] The new unit formed part of the Lancashire Division of the Royal Artillery, then transferred to the Southern Division. Initially it had six batteries of garrison artillery, but it was soon converted to the new role of 'Position artillery', with three semi-mobile batteries to work alongside the Volunteer infantry brigades. Of the batteries, Nos 1 and 2 were based at Bolton, No 3 at Southport.[1][3][4][5][6] The unit's first commanding officer (CO) was Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Winder, who had commanded the old 18th Lancashire AV and then served as second-in-command of the 3rd.[6]

On 1 June 1899 all the Volunteer artillery units became part of the Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA) and with the abolition of the divisional organisation on 1 January 1902, the unit became the 9th Lancashire Royal Garrison Artillery (Volunteers). From 1904 it was commanded by Lt-Col Robert Cecil Winder, son of the first CO.[1][3][6] 'Position artillery' was redesignated 'heavy artillery' in May 1902.[5]

Territorial Force

When the Volunteers were subsumed into the new Territorial Force (TF) under the Haldane Reforms of 1908,[7][8] the unit became the III (or 3rd) East Lancashire Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, consisting of the 18th, 19th and 20th Lancashire Batteries and the III East Lancashire Brigade Ammunition Column (BAC). From March 1909 it was granted the subtitle 'The Bolton Artillery', alongside the Manchester Artillery (II East Lancs) and Cumberland Artillery (IV East Lancs). The brigade formed part of the TF's East Lancashire Division and was equipped with four 15-pounder field guns to each battery. On the outbreak of war the brigade was commanded by Lt-Col C.E. Walker, TD.[1][3][6][2][9][10][11][12]

First World War

Mobilisation

Units of the East Lancashire Division had been on their annual training when war came: on 3 August they were recalled to their drill halls and at 17.30 next day the order to mobilise was received. The men were billeted close to their drill halls while the mobilisation process went on.[11][12][13]

On 10 August, TF units were invited to volunteer for Overseas Service. The infantry brigades of the East Lancashire Division volunteered by 12 August and soon 90 per cent of the division had signed up. On 15 August 1914, the War Office issued instructions to separate those men who had opted for Home Service only, and form these into reserve units. On 31 August, the formation of a reserve or 2nd Line unit was authorised for each 1st Line unit where 60 per cent or more of the men had volunteered for Overseas Service. The titles of these 2nd Line units would be the same as the original, but distinguished by a '2/' prefix and would absorb the flood of volunteers coming forwards. In this way duplicate batteries, brigades and divisions were created, mirroring those TF formations being sent overseas.[14][15][16]

Egypt

On 20 August the East Lancashire Division moved into camps around Bolton, Bury and Rochdale, and on 5 September it received orders to go to Egypt to complete its training and relieve Regular units from the garrison for service on the Western Front. It embarked on a convoy of troopships from Southampton on 10 September, and landed at Alexandria on 25 September, the first complete TF division to go overseas. 1/III East Lancs Bde was commanded by Lt-Col Walker. Some units moved into the Suez Canal defences in October before war broke out with Turkey on 5 November. 1/III East Lancs Bde was sent to the Canal Zone on 20 January 1915 and its guns were concealed among trees on the west bank, with 1/18th Bty at Ferry Post, Ismailia, 1/19th at Serapeum West and 1/20th at El Ferdan. The Turks reconnoitred these positions on 2 February and 1/20th Bty at El Ferdan claimed the distinction of being the first battery of the division (and probably the first in the TF) to fire upon an enemy. 1/19th Battery under Major B.P. Dobson was also in action against skirmishing Turkish camel troops. In the early hours of 3 February the Turks attempted a crossing of the canal. 1/19th Battery hauled a 15-pdr through a wood to the canal bank and fired point-blank into the iron pontoons that the Turks were trying to launch. Another gun was hauled to a hill behind the wood and found good targets among the enemy approaching the canal. 1/18th Battery fired on enemy positions at ranges of 3,000 yards (2,700 m) to 2,000 yards (1,800 m). The brigade's casualties were only five men wounded, four of these in 1/19th Bty. The Turks did not press home their attack and retired after Indian infantry counter-attacked. The brigade then resumed training.[6][11][12][17][18][19]

Gallipoli

On 1 May the division began embarking for the Gallipoli campaign. Only 24 of the division's guns were taken in the first lift; 1/III East Lancs Bde contributed 1/18th Bty. The guns began landing on 9 May at Cape Helles, where an assault landing had been carried out on 25 April and the division's infantry had already been in action for three days. The beachhead was so congested that only a few guns of 1/I East Lancs Bde got ashore while 1/18th Bty and the rest of the artillery was ordered to return to Egypt. The battery did not finally reach the peninsula until 27 July. On 7 August the division was called upon to make a diversionary attack against Krithia Vineyard to cover a new landing further up the coast. The bombardment, with British, French and naval guns contributing, began at 08.10 and increased in intensity at 09.00. Although the fire was accurate, the Turkish trenches suffered little damage. The infantry went forward at 09.40, wearing tin triangles on their backs so that the artillery observation posts (OPs) could track their progress. The attack was partially successful, the vineyard being captured, but casualties were heavy. However, the Turks had been pinned while the main attacks went ahead, and they in turn suffered heavy casualties in their counter-attacks.[11][12][20][21][22][23]

After a short period in reserve, 42nd (EL) Division spent the following months engaged in Trench warfare, suffering from sickness, and then from bad weather as winter set in.[24][25] 1/19th and 1/20th Batteries arrived at Helles on 24 September, but the BAC remained in Egypt.[20][21] Between 27 and 31 December the exhausted infantry of 42nd (EL) Division were evacuated from Helles to Mudros, but the 42nd Divisional Artillery (42nd DA) stayed behind, supporting 13th (Western) Division. The last Turkish attack at Helles was beaten off on 7 January 1916, but a full evacuation was already under way. As 13th (W) Division's modern guns were withdrawn, they were replaced with the old ones of 42nd (EL) Division, so that fire was maintained without obvious slackening. Finally, those old guns that could not be got away were destroyed, and 13th (W) Division was evacuated to Mudros on the night of 8/9 January.[11][12][26][27][28][29]

Egypt again

42nd (EL) Division was then sent from Mudros back to Egypt, the bulk of the RFA embarking on 14 January in a storm. The division concentrated at Mena Camp on 22 January before moving into southern sector of the Suez Canal defences. Once back in Egypt 1/III East Lancs Bde was reunited with its BAC and on 27 February 1916 was rearmed with modern 18-pounder guns handed over by 29th Division as it left for the Western Front.[11][30][31] On 31 May 1916 1/III East Lancs Bde was numbered CCXII (212) Brigade, RFA, and the batteries were designated A, B and C.[10][11][12][9][32][33]

The canal defences were now situated east of the waterway, with a string of self-contained posts, each garrisoned by an infantry battalion and an artillery battery. The division did much of the construction and then trained in the desert, the gunners carrying out field firing with their new guns. The gun wheels were fitted with 'ped-rails' to assist movement across soft sand, for which 12 rather than 6 horses were harnessed to gun-carriages and limbers. In late July the division was ordered north, where a Turkish force was advancing on the defences. On 30 July mobile columns were ordered forward, and one of these was formed by 127th (Manchester) Brigade accompanied by A Bty of CCXII Bde, which moved up to Hill 70. The Turkish force was defeated at the Battle of Romani near Pelusium on 4–5 August, after which 127th Bde set off in pursuit. The men and horses suffered badly from lack of water, A Bty struggling to keep up with the advance, but it finally came into action and the retreating Turks lost heavily. The division then returned to the Romani and Pelusium area by 15 August, the bulk of the artillery and ammunition columns at Kantara and Ballah, but with A/CCXII Bty at Romani.[11][12][34][35][36]

For the next few months the division was part of the Desert Column covering the extension of the railway and water pipeline into the Sinai Desert to permit the Egyptian Expeditionary Force to mount an offensive into Palestine. The head of the Desert Column reached El Arish, near the Palestine frontier, on 22 December.[37][38] On 25 December 1916 CCXII Bde was redesignated CCXI (211) Brigade, exchanging numbers with the former 1/II East Lancs (Manchester Artillery) Bde, which was broken up shortly afterwards. At the same time the Bolton brigade was reorganised: C Bty was split between A and B to bring them up to six guns each and A (Howitzer) Bty joined from CCXIII Bde (formerly 1/1st Cumberland (H) Bty in IV East Lancashire Howitzer Brigade (The Cumberland Artillery)) and became C (H) Bty, equipped with 4.5-inch howitzers. On 10 February 1917 C (H) Bty was redesignated D (H), and B/CCXII Bty joined as C Bty.[10][11][9]

On 28 January 1917, after the division reached El Arish, orders arrived for it to be sent to the Western Front. By 12 February the division had withdrawn to Moascar, and on 22 February the division began embarking at Alexandria for Marseille.[11][12][39][40]

France and Flanders

On 7 March trains from Marseille brought CCXI Bde to 42nd (EL) Lancashire Division's concentration point at Pont-Remy, near Abbeville. The Divisional Ammunition Column (DAC) had been left in Egypt (becoming the DAC for 74th (Yeomanry) Division) and on arrival in France, the BACs were abolished (this had been done long before in divisions on the Western Front) to reform a new 42nd DAC, to which CCXI BAC contributed No 2 Section, the rest of the men joining the batteries. The batteries drew their guns from the ordnance store and began training. An advance party from Egypt had already served some time in the line attached to units of 1st Division for familiarisation.[11][41][42][43]

From 8 April 42nd (EL) division moved into the line around Épehy in the Somme sector, which had just been abandoned by the Germans as they withdrew to the Hindenburg Line. It began taking over a sector from 48th (South Midland) Division, and CCXI Bde's batteries were attached to that formation for familiarisation. A considerable amount of work had to be done to repair the roads and prepare new positions. The artillery also supported small attacks to capture Hindenburg Line outposts, such as one on The Knoll and Guillemont Farm on 24 April, when Lt-Col Walker had tactical command of his own C Bty and one from 48th (SM) Division. 42nd DA then relieved 20th (Light) Division's artillery at Havrincourt Wood on 23 May.[12][44][42]

D (H) Battery was finally made up to six howitzers on 19 June 1917 when a section joined from C (H) of CCXCVIII Bde in 59th (2nd North Midland) Division (this was a Kitchener's Army unit, originally 3 (H)/LIX Bty, from 11th (Northern) Division). The brigade's final organisation, therefore, was as follows:[11][42][45][46]

- A Bty (1/18th Lancashire Bty + half 1/20th Lancashire Bty) – 6 x 18-pdr

- B Bty (1/19th Lancashire Bty + half 1/20th Lancashire Bty) – 6 x 18-pdr

- C Bty (1/17th Lancashire Bty + half 1/16th Lancashire Bty) – 6 x 18-pdr

- D (H) Bty (1/1st Cumberland (H) Bty + section C (H)/CCXCVIII Bty) – 6 x 4.5-inch

On 8 July 42nd (EL) Division was relieved by 58th (2/1st London) Division but the artillery remained at Havrincourt to support the newcomers, and later 9th (Scottish) Division when it took over the sector from the 58th. Its role was to fire concentrations into the enemy's rear areas at night, particularly on roads, patrol paths and where reliefs were suspected of being carried out, and to engage enemy batteries by day. Single guns were posted in camouflaged to carry out this fire, to avoid retaliation on battery positions; the brigade established seven of these, known as 'pirates'.[42][47]

After the infantry of 42nd (EL) Division had completed their rest period the division was sent to the Ypres Salient where the Third Ypres Offensive was under way. CCXI Brigade marched back to Péronne on 25 August, where it entrained for Godeswersvelde and then marched to Watou. On 29 August it took over positions at Potijze Chateau east of Ypres. Here Lt-Col Walker assumed command of the Right Subgroup, comprising both brigades of 42nd DA and 14th Australian Field Artillery Bde. The salient was packed with guns and the 18-pdrs stood almost wheel to wheel in mud just behind the front line infantry, with the 4.5s in groups, also close to the front line. The subgroup was engaged in a continuous bombardment of German positions south of Zevenkote. On 6 September 125th (Lancashire Fusiliers) Brigade carried out a limited operation behind a Creeping barrage to capture strongpoints around Borry Farm. This failed, though the guns drove off German counter-attacks. Casualties were heavy on the gun positions from enemy counter-battery (CB) fire and among the drivers bringing ammunition up shell-swept roads at night. On 7 September Gunner S. Hardcastle of B Bty left cover to rescue a wounded comrade under heavy shelling, and three days later he ran across to extinguish a fire in an adjacent battery's ammunition dump. The division was withdrawn to the Flanders coast on 20 September, but once again 42nd DA remained in the line, supporting V Corps's successful attack at the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge on 20 September, then moving up onto Frezenberg Ridge on 25 September to prepare for next day's Battle of Polygon Wood. The artillery engagements were intense, and it was not unusual for a battery to fire 5000 rounds in a day. The gunners suffered heavy casualties from gas shelling: during September CCXI Bde suffered casualties of 2 officers and 7 other ranks (ORs) killed, 3 officers and 40 ORs wounded, and 4 officers and 76 ORs gassed, including Lt-Col Walker who was gassed and evacuated on 9 September. Lieutenant-Col E.J. Inches arrived on 18 September to take over command.[19][42][48][49][50]

CCXI Brigade was relieved in the line over the nights of 28/29 and 29/30 September and marched to join the infantry of 42nd (EL) Division in the line near Nieuport on the Flanders Coast. On the nights of 2/3 and 3/4 October relieved CCCXXXI Bde (formerly 2/II East Lancs Bde) of 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division. Earlier in the year British troops had been concentrated here for a planned thrust up the coast, but with the Ypres offensive bogged down this operation had been abandoned. However, German artillery and aircraft were very active, shelling and bombing the British gun positions and canal crossings. When Major-General Arthur Solly-Flood took command of the division in October he instituted an improved system of retaliatory fire, known as 'Punishment Fire'. When the Germans began a heavy bombardment while the division was being relieved by French troops on 19 November, the Punishment Fire silenced the German guns in 20 minutes.[11][12][51][52]

After marching south, the division went into the line in the La Bassée sector on 29 November. It remained here during the winter, carrying out normal trench duty. 42nd DA saw considerably more action than the rest of the division, and the Punishment Fire system was regularly used. The targets most likely to inconvenience the enemy were carefully registered so that when the intensity of German shelling increased, Punishment Fire could be brought down employing everything from 18-pdrs to 15-inch howitzers. The biggest trench raid carried out by the division was on 11 February 1918 opposite Festubert where the raiders were protected by a Box barrage. The division was relieved on 15 February, but as usual 42nd DA stayed in place for a few days longer before coming out of the line for training near Chocques.[6][11][42][53]

Spring Offensive

42nd (EL) Division was in GHQ Reserve when the German Spring Offensive (Operation Michael) was launched on 21 March. Warning orders were immediately issued and on 23 March the division began moving south to the Somme sector. The infantry went by motor buses and arrived at Adinfer Wood ahead of the artillery and transport, which did not catch up for another two days through the crowded roads. The infantry deployed on the night of 24/25 March and were engaged in bitter fighting throughout 25 March (the First Battle of Bapaume). 42nd DA began arriving at noon, with CCXI Bde opening fire as soon as it got within extreme range, laying down a barrage near Logeast Wood. At nightfall the infantry were still holding the line they had taken up the previous night, but were now stretched very thinly, with both flanks 'in the air'. The artillery was ordered back to positions south of Ablainzevelle, and a few hours later to the Essarts Valley. The roads behind the front were now completely choked with retreating vehicles, and the artillery drivers bringing up ammunition suffered heavy casualties. 42nd (EL) Division's role was to screen the exhausted divisions behind them. During 26 March 42nd DA helped stop German attacks in front of Bucquoy, with CCXI Bde shelling the long enemy columns marching into Achiet-le-Petit. On 27 March the guns broke up two impending attacks from Ablainzevelle. On 28 March the Germans continued attacking in waves from Ablainzevelle and Logeast Wood (Operation Mars, or the First Battle of Arras of 1918), but the division held its positions; the following day was quiet and 42nd (EL) Division was relieved on the night of 29/30 March. However, there was no rest for 42nd DA, which remained in action round Essarts. The infantry returned to the line on 1/2 April. The Germans continued to shell the area, especially Essarts, where large numbers of gas shells were fired and 42nd DA suffered significant casualties. After this bombardment the German attack was renewed on 5 April (the Battle of the Ancre). This attack was repulsed after fierce fighting and the sector became quiet apart from artillery exchanges; the division was relieved from 8 April and on 10 April CCXI Bde handed over its guns in position and marched out for rest.[11][12][42][54][55][56]

After a week's rest 42nd (EL) Division returned to the line near Gommecourt, where it spent a relatively quiet summer, reorganising the old German positions from the Battle of the Somme as up-to-date defences. The batteries were distributed in depth so that some were available in each defence zone, and the gunners were instructed in using the rifle to defend their positions. Although German artillery was active with Mustard gas shells, there was no attack. 42nd DA remained in position while the infantry went out of the line on 7 May. When the infantry returned on 7 June the division took up a wide sector from Hébuterne to Auchonvillers. 42nd DA fired covering barrages for raids and regularly shelled German positions in Serre and Puisieux. On 4 May A and B Btys shelled Rossignol Wood with Thermite shells in an attempt to set it on fire and then the brigade participated in a box barrage to cover an attack by 1st New Zealand Brigade. C Bty spent a period from 19 April as a 'silent' battery, but this did not prevent it being heavily shelled on 11 May when a nearby heavy battery opened fire. 42nd DA adopted a policy of 'silent hours' to allow sound-rangers to locate active enemy batteries. 42nd (EL) division suffered badly from the Spanish flu epidemic, and in July its frontage was reduced to match its weakened strength.[42][57]

Hundred Days

Through aggressive raiding, 42nd (EL) Division pushed the German outposts back several hundred yards during the summer. After the Allies launched their counter-offensive (the Hundred Days Offensive) at the Battle of Amiens on 8 August, patrols from the division found the enemy preparing to withdraw on their front. 42nd DA pounded the German trenches and roads to disrupt this move, and follow-up patrols found the trenches 'obliterated' by the 4.5-inch howitzers. By 20 August the division had advanced beyond Serre and Puisieux. On 21 August it was ordered by IV Corps to make a full-scale attack as part of the Battle of Albert. The infantry advanced behind a creeping barrage accurately fired by the divisional artillery despite the lack of previous registration. Although for this attack 42nd (EL) Division was organised into brigade groups, with each RFA brigade integrated with the infantry brigade it was to support, in fact the whole of 42nd DA supported first 125th (Lancashire Fusiliers) against Hill 140 and the Beauregard Dovecot, then 127th (Manchester) Bde, and then switched back to 125th Bde for the second objective. Next day the Germans attempted a dawn counter-attack on the division, but this miscarried badly, the guns were brought forward, and on 23 August the 42nd renewed its advance. It assaulted the commanding ridge north of Miraumont with the support of its own artillery and that of the New Zealand Division, and captured it without difficulty. Over the next two days it took Miraumont itself and moved on towards Warlencourt-Eaucourt. The 42nd became the reserve division on 25 August, but 63rd (Royal Naval) Division got into difficulties and 42nd DA was rushed up to assist, the gun teams of CCX and CCXI Bdes racing each other into position by Loupart Wood and coming into action immediately. Unfortunately two gun teams of C Bty were blown up by improvised mines laid by the Germans in the road.[11][12][42][58][59][60] Lieutenant-Col Inches had returned to the UK some weeks previously, and on 22 August Lt-Col F.G. Crompton was posted from 62nd Divisional Artillery to take over command of CCXI Bde.[19][42]

42nd (EL) Division relieved 63rd (RN) Division in the line on the night of 27/28 August, and fighting patrols followed the retiring enemy. CCXI Brigade laid down 'annihilating' fire across the south end of Bapaume to hinder their retreat. Where significant resistance was encountered, a battalion attack was organised with a preliminary bombardment and creeping barrage laid on by 42nd DA. The biggest of these was the night attack by 10th Manchester Regiment at Riencourt-lès-Bapaume on 30/31 August. For the attack on Villers-au-Flos on 2 September 42nd DA was reinforced by brigades from three other divisions, and a section of C/CCXI Bty was directly attached to one of the advancing infantry battalions. Because the division was starting from further back than the neighbouring New Zealanders the creeping barrage was dropped further ahead of the infantry (400 yards (370 m) instead of the usual 200–250 yards (180–230 m)) and was begun 9 minutes ahead of Zero hour; unfortunately this alerted the enemy to the attack. Nevertheless, the Manchesters captured Villers-au-Flos. That night the artillery bombarded Barastre and Haplincourt Wood in preparation for the next attack, but patrols early on 3 September found them empty and the division quickly followed up, reaching Ytres by the end of the day. It had fighting patrols across the Canal du Nord by the end of 4 September, the only hold-ups coming from destroyed roads and bridges, and incessant mustard gas shelling. 42nd (EL) Division was relieved by the New Zealand Division on the night of 5/6 September, with 42nd DA at Ytres coming under New Zealand Divisional Artillery.[11][12][42][61] ref>Gibbon, pp. 162–8.</ref>

The Germans were now back in the Hindenburg Line, and the Allies had to clear the outposts before they could tackle the main defences. CCXI Brigade fired a creeping barrage for the New Zealanders in the successful Battle of Havrincourt on 12 September, at the end of which a German counter-attack was broken up by artillery fire.[62][63] On return to 42nd (EL) Division, the artillery brigades were given several days' rest, during which CCXI Bde's horse lines were heavily bombed on the night of 15/16 September, B and C Btys losing 85 horses and mules killed, and many more injured. The division then went back into the line to prepare for the next phase of the offensive, the Battle of the Canal du Nord. On the night of 25/26 September the guns of all four batteries were taken into position in the north-east corner of Havrincourt Wood, the gunners occupying the gun positions the following night. The assault went in against the Hindenburg Line on 27 September, CCXI Bde firing a creeping barrage for 125th Bde. Unfortunately the 7th and 8th Lancashire Fusiliers were caught by enfilade fire from the high ground around Beaucamps and by machine guns in front that had not been suppressed by the barrage: the leading companies were practically wiped out. The brigade persisted, reaching its first objective around midday, and CCXI Bde fired another creeping barrage for it that evening, but the results were disappointing compared to the great victory achieved elsewhere. 5th Lancashire Fusiliers renewed the attack under moonlight behind a terrifying creeping barrage: by 06.00 on 28 September they were closing on Highland Ridge, the previous day's final objective, and the enemy were withdrawing towards Welsh Ridge, which was taken later that day. For the attacks of 29–30 September the New Zealand Division passed through 42nd, and CCXI Bde fired a creeping barrage for their attack on La Vacquerie. The brigade was the first artillery to follow up the advance and found considerable difficulty in crossing the old Hindenburg Line defences onto Welsh Ridge.[11][12][42][64][65]

IV Corps had now closed up to the west bank of the St Quentin Canal and the New Zealand Division had established a bridgehead. By 4 October there were signs of enemy withdrawals, and over the following days the brigade moved up across the Escaut Canal, firing in support of the advancing New Zealanders (the Second Battle of Cambrai). On 9 October the infantry of 42nd (EL) Division relieved the New Zealanders and next day the artillery followed up to Fontaine-au-Pire. On 12 October 125th Bde took over the front including the bridgeheads that the New Zealanders had established across the River Selle. The Germans desperately tried to retake these bridgeheads and there was hard fighting. 42nd (EL) Divisional Engineers bridged the Selle on the nights of 17–19 October, and the advance resumed at 02.00 on 20 October (the Battle of the Selle). The barrage included incendiary shells to mark its centre and flanks for the infantry advancing in the darkness. This was so successful on CCXI Bde's front that the barrage was called off early; the guns later broke up a German attempt at a counter-attack. 125th Brigade attacked again on 23 October, with CCXI Bde providing a creeping barrage. It then moved forward to near Vertigneul in order to fire a second barrage for the New Zealanders to cross the St Georges river and capture Beaudignies.[11][12][42][66][67]

After the Battle of the Selle 42nd (EL) Division went into reserve around Beauvois; as usual 42nd DA remained in the line, with CCXI Bde at Beaudignies, but the line was quiet for a time. On 2 and 3 November the batteries took up positions nearer the front and next day they fired a barrage for the New Zealanders' attack on Le Quesnoy. D Battery came under heavy fire, suffering heavy casualties and having five howitzers put out of actyon. However, the rest of the brigade moved up close to Le Quesnoy to support the New Zealanders' advance to the final objective. 42nd (EL) Division was then brought up to penetrate into the Forêt de Mormal. CCXI Brigade was left behind, but on 9 November it moved up to Hautmont on the River Sambre, which the infantry had liberated the day before. The division had now lost touch with the retreating enemy. Hostilities ended on 11 November with the Armistice with Germany and the brigade stood fast on the line it had reached.[11][12][42][68][69]

42nd (EL) Division remained at Hautmont until 14 December, when it began moving to winter quarters near Charleroi in Belgium, with CCXI Bde billeted in and around Montignies-sur-Sambre. Demobilisation got under way in January 1919 and CCXI Brigade completed the process some time after 24 March 1919.[11][12][42]

Complete casualty figures for 42nd (East Lancashire) Divisional Artillery are not available, but the divisional history lists 84 ORs killed, died of wounds or sickness, from 1/III East Lancs Bde and a further 69 from CCXI Bde.[70]

2/III East Lancashire Brigade, RFA

The 2nd Line units of the East Lancashire Division were raised in September and October 1914, with only a small nucleus of instructors to train the mass of volunteers. Training was slow because the 2nd Line artillery lacked guns, sights, horses, wagons and signal equipment.[10][71][72] The 2nd East Lancashire Division, now numbered 66th (2nd EL) Division, began concentrating in Kent and Sussex in August 1915. 2/III East Lancs Bde was given four old French De Bange 90 mm guns for training, and it was not until November and December that it received its 18-pdrs. In early 1916 the division moved into the East Coast defences, with its artillery at Colchester.[10][9][71][72][73]

In May 1916 the brigade was numbered as CCCXXXII (332) Brigade and the batteries were designated A, B and C. At the same time 2/IV East Lancs Bde (The Cumberland Artillery) was broken up and 2/2nd Cumberland (Howitzer) Bty joined CCCXXXII as D (H) Bty.[10][9][71] After long delays caused by having to find reinforcement drafts for 42nd (EL) Division (supplying one draft of 250 gunners in 1916 considerably delayed the whole division), 66th (2nd EL) Division was finally ready for overseas service at the end of 1916. Before leaving England C Bty was split up to make A and B Btys up to 6 guns each. D (H) Battery was split up between the other two brigades of the division, and a new C (H) Bty joined CCCXXXII Bde.[71]

66th (2nd EL) Division was ordered to France on 11 February 1917 and on 4 March CCCXXXII Bde entrained at Colchester for Southampton. It boarded the SS Karnak the same night, but did not sail. The brigade was disembarked on 6 September and sent to a rest camp until 12 September when it re-embarked. The brigade disembarked from the Karnak at Le Havre next day and entrained for Haverskerque. It marched into Lestrem on 22 March. It had been decided to withdraw CCCXXXII Bde from the division to become an independent Army Field Artillery (AFA) brigade, and 66th Divisional Ammunition Column had formed a dedicated BAC for it drawn from the DAC's 2nd Echelon. However, the brigade was broken up before going into the line. A Battery was transferred to CCXCVIII AFA Bde on 11 April, the signallers went back to 66th DA, and on 30 April B Bty went to complete a composite battery serving under 1st Canadian Division. The newly formed C (H) Bty went to First Army Artillery School, then to 49th (West Riding) Division and later was broken up.[10][9][71][74][75]

Interwar

When the TF was reconstituted on 7 February 1920, III East Lancs Bde reformed at Bolton with 17–20 Lancashire Btys. In 1921 the TF was reorganised as the Territorial Army (TA) and the unit was redesignated as 53rd (East Lancashire) Brigade, RFA, with 205–208 (East Lancashire) Btys. The following year the designation was changed to 53rd (Bolton) Brigade, RFA, with the following organisation:[6][10][76]

- Brigade HQ at Drill Hall, Silverwell Street, Bolton

- 209, 210, 211 (East Lancashire) Btys

- 212 (East Lancashire) Bty (Howitzer)

The brigade was once again part of 42nd (EL) Divisional Artillery. In 1924 the RFA was subsumed into the Royal Artillery (RA), and the word 'Field' was inserted into the titles of its brigades and batteries.[6][10][76][77] The establishment of a TA divisional artillery brigade was four 6-gun batteries, three equipped with 18-pounders and one with 4.5-inch howitzers, all of First World War patterns. However, the batteries only held four guns in peacetime. The guns and their first-line ammunition wagons were still horsedrawn and the battery staffs were mounted. Partial mechanisation was carried out from 1927, but the guns retained iron-tyred wheels until pneumatic tyres began to be introduced just before the Second World War.[78] In 1938 the RA modernised its nomenclature and a lieutenant-colonel's command was designated a 'regiment' rather than a 'brigade'; this applied to TA field brigades from 1 November 1938.[6][10][76]

After the Munich Crisis the TA was rapidly expanded. On 8 April 1939 Harry Goslin, captain of the Bolton Wanderers football team, announced to the crowd at Burnden Park that after the match he and his team would go to the TA drill hall to sign up. Most of the team was posted to 53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment.[79]

With the expansion of the TA, most regiments formed duplicates. Part of the reorganisation was that field regiments changed from four six-gun batteries to an establishment of two batteries, each of three four-gun troops. For the Bolton Artillery this resulted in the following organisation from 25 May 1939:[10][76][80][81]

- Regimental Headquarters (RHQ) at Silverwell Street, Bolton

- 209 (East Lancashire) Field Bty

- 210 (East Lancashire) Field Bty

111th Field Regiment

- RHQ at Bolton

- 211 (East Lancashire) Field Bty

- 212 (East Lancashire) Field Bty

Second World War

Mobilisation

The Bolton Artillery mobilised on 1 September 1939, just before the outbreak of war, as part of 42nd (EL) Infantry Division, but from 27 September the newly formed 66th Infantry Division took over the duplicate units including 111th Fd Rgt.[82][83][84][85]

53rd (Bolton) Field Regiment

Battle of France

53rd (Bolton) Fd Rgt was still equipped with 18-pounders on the outbreak of war. The division began crossing to France in April 1940 to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).[84][83][86] When the German offensive began on 10 May, the BEF advanced into Belgium under Plan D, and by 15 May 42nd (EL) Division was in position on the River Escaut in France. It began Defensive Fire (DF) tasks three days later and fired 6000 rounds in its first 36 hours of war.[87] But the Wehrmacht's breakthrough in the Ardennes threatened the BEF's flank, and it had to retreat again.[83][84][88][89][87] As the Germans thrust behind the BEF, 42nd (EL) Division found itself south of Lille and facing east. On 26 May 53rd Fd Rgt was ordered back to Dunkirk where the BEF was to be evacuated.[90][91][92]

Units returning from France were rapidly reinforced, re-equipped with whatever was available, and deployed for home defence.[93] Field regiments were reorganised into three batteries, and 53rd Fd Rgt accordingly formed 438 Fd Bty by 29 March 1941.[76] In the autumn of 1941 it was decided to convert 42nd (EL) Division into an armoured division. 52nd (Manchester) and 53rd (Bolton) Fd Rgts left on 20 October,[84] and joined 76th Infantry Division defending Norfolk. During 1942 large reinforcements were sent from the UK to Middle East Forces, and 53rd Fd Rgt was chosen to join them.[76][94]

Middle East

In Egypt it joined Eighth Army and was attached to 44th (Home Counties) Division for the Second Battle of El Alamein, which was launched on the night of 23/24 October behind a massive artillery barrage.[95] After the battle 44th (HC) Division HQ was disbanded, and 53rd Field Rgt now became an army level unit in Middle East Forces.[96][97] It was sent to Iraq, where it came under the command of 8th Indian Division (along with 52nd (Manchester) Fd Rgt).[98] The division was in Paiforce defending the vital oilfields of Iraq and Persia and the line of communications with the Soviet Union.[99][100] By the spring of 1943 the victories in North Africa and on the Eastern Front had removed the threat to the oilfields, and troops could be released from Paiforce. 8th Indian Division moved to Syria and was then selected for the forthcoming Italian campaign.[98]

Italy

Landing in Italy in September,[98][101] the division joined Eight Army's advance up the east coast of Italy, attacking across the River Trigno (1–4 November) where a German counter-attack 'was blown to pieces by the divisional artillery'.[102] 8th Indian Division then captured Mozzagrogna in the Bernhardt Line.[103] It continued advancing with short, powerfully supported attacks against stubborn resistance, where artillery ammunition supply became the limiting factor, until winter weather brought an end to operations.[104]

In May 1944 the division made an assault crossing of the Rapido in Operation Diadem) with a massive artillery programme.[105][106] The Germans retired to the Hitler Line, but once the guns were brought up they totally suppressed the German artillery. While the armoured divisions advanced up the roads, the lightly equipped 8th Indian Division took to the narrow tracks through the hills, driving German rearguards from the hilltop towns.[107][108]

For the attack on the Gothic Line (Operation Olive, 8th Indian Division crossed the River Arno on 21 August, and then advanced into the roadless mountains before opening the routes into the Lamone Valley. The gunners had particular problems in firing over crests to hit targets behind, and artillery ammunition also had to be rationed from November.[109][110] On 26 December the Germans launched a counter-attack (the Battle of Garfagnana) but 8th Indian Division had already been rushed to bolster the US sector concerned and the German attack was not pressed.[111]

In the Allies' spring 1945 offensive, Operation Grapeshot, 8th Indian Division was given the task of an assault crossing of the River Senio, with massive artillery support added to its own guns, and ample ammunition stocks built up during the winter. It then secured crossings over the River Santerno, and by cutting round Ferrara it was the first formation of Eighth Army to reach the River Po on 23 April. German resistance was crumbling and there was little opposition to its crossing on the night of 25/26 April.[112]

Hostilities on the Italian Front ended on 2 May with the Surrender of Caserta, but 8th Indian Division had already been withdrawn from the line as the first Indian formation to transfer to the Far East to fight the Japanese. 52nd (Manchester) Fd Rgt embarked for the UK on 27 July.[10][76][98][113][114] Back in the UK it became a holding regiment. It passed into suspended animation on 2 June 1946.[10][76][98]

111th (Bolton) Field Regiment

After the BEF was evacuated from Dunkirk, Home Forces underwent a reorganisation to meet a potential German invasion. As part of this, 66th Division was disbanded on 23 June 1940 and 111th Fd Rgt reverted to 42nd (East Lancashire) Division from 3 July 1940.[84][85] Like 53rd Fd Rgt, it formed its third battery, 476, on 29 November 1940.[80] From 31 October 1941, when 42nd (EL) Division converted to armour, 111th Field Rgt became an Army Field Rgt in Scottish Command, with a dedicated signal section from the Royal Corps of Signals and Light Aid Detachment (LAD) from the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (later Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers).[115] On 17 February 1942 it was authorised to adopt the 'Bolton' subtitle of its parent regiment.[80]

Mediterranean

111th (Bolton) Fd Rgt was also sent to Egypt in the summer of 1942. It was temporarily attached to 50th (Northumbrian) Division for the Battle of Alamein,[80][116][117] after which it reverted to Eighth Army command for the pursuit across North Africa.[116] For the Battle of Mareth in March 1943, it was attached to 2nd New Zealand Division HQ, which was operating as a temporary corps HQ.[118]

111th Field Rgt served as an Army Fd Rgt in the Italian Campaign.[119] For the fighting on the Sangro during the attack on the Bernhardt Line in November 1943 it was attached to 8th Indian Division, fighting alongside 53rd (Bolton) Fd Rgt.[120]

Yugoslavia

In January 1944 a British force was established on Vis, an island off the coast of Yugoslavia, to cooperate with the Yugoslav Partisans. By May 1944 Vis Brigade included 111th Field Rgt.[121] In September the Germans began withdrawing from Greece, and British forces raided their lines of retreat along the Balkan coast. 111th Field Rgt participated in raids on the islands of Korčula on 14–17 September and Šolta on 19–23 September, and in the capture of Sarandë on 9 October.[122][123] The Partisans were impressed by the power of the artillery in these raiding forces and began to demand help from British artillery. A force landed at Dubrovnik on the mainland on 27 October 1944, with the initial landings by a mixed artillery force under the commanding officer of 111th Fd Rgt.[124] Using a tortuous mountain route the leading troop of 211 Fd Bty came into action against German positions at Risan. The guns breached the old Austrian fortifications and Risan was entered on 21 November. Several proposed operations were vetoed by the Yugoslav commanders but 212 Fd Bty made its way to towards Podgorica along a track that had to be repaired by British engineers and working parties of Partisan men and women. On the night of 13/14 December the battery deployed within range of the German positions outside Podgorica and opened fire next day. Over the next 11 days the guns edged forwards as the tracks were cleared, and 476 Fd Bty was also brought up. Podgorica was captured and although the guns could not cross the broken bridges, they continued firing on the retreating Germans until they were out of range on 24 December.[124][125]

111th Field Rgt returned to Dubrovnik on 26 December and prepared for further operations, but were not called upon by the Yugoslavs. By the end of January 1945 the force had been withdrawn to Italy, and all troops had left by the end of the month.[126] Demobilisation began shortly after the Surrender of Caserta, and 111th (Bolton) Field Rgt passed into suspended animation on 10 November 1945.[80]

Postwar

The TA was reconstituted on 1 January 1947, when 53rd Fd Rgt was reformed as 253 (Bolton) Fd Rgt in 42nd (Lancashire) Division. 111th (Bolton) Field Rgt was formally disbanded at the same time.[10][76][80][127][128][129][130][131] Just before its annual camp on 10 June 1955 the regiment absorbed some personnel from 652 (5th Battalion Manchester Regiment) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Rgt, which was disbanding following the abolition of Anti-Aircraft Command.[128][132]

The TA was reorganised on 1 May 1961, when Q Bty of 253 Rgt left to join 436 (South Lancashire Artillery) Light Anti-Aircraft Rgt and was replaced by Q (Salford) Bty from 314 Heavy Anti-Aircraft Rgt.[128][133]

When the TA was reduced into the Territorial and Army Volunteer Reserve (TAVR) on 1 April 1967, 253 Rgt provided F Troop (The Bolton Artillery) of 209 (Manchester Artillery) Light Air Defence Battery in 103 (Lancashire Artillery Volunteers) Light AD Rgt a Volunteer unit in TAVR IIA.[10][134] Simultaneously, other personnel from 253 Rgt converted to infantry as D Company (The Bolton Artillery) in 4th (Territorial) Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment, in TAVR III. However, that battalion was reduced to a cadre two years layer and that Bolton Artillery lineage ended.[10][135]

In 1987 F Troop was expanded to battery size, and continues today as 216 (Bolton Artillery) Battery in 103 (Lancashire Artillery Volunteers) Rgt.[10]

Honorary Colonels

The following served as Honorary Colonel of the unit:[6]

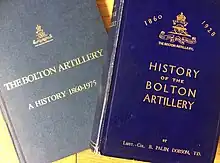

Books on the Bolton Artillery

Three books have been published. The first, ‘History of the Bolton Artillery 1860 - 1928’ was written by Lt Col B. Palin Dobson a former Commanding Officer of the Brigade with war service and committee member for many years. A print run of 250 was made in 1929 and it is a rare book today. In 1930, 142 copies had remained unsold. The BVAA agreed to pay the printing costs. He notes in the preface, ‘In the year 1923 at the wish of many officers and ex officers of the Bolton Brigade of Artillery, the writer compiled a history of the Bolton Artillery. It consisted of the bare facts arranged in chronological order commencing from the formation of the Corps’. It is a remarkable book, almost forensically written and forms the definitive record of the period. Little original written material has been preserved in the archive of the Bolton Artillery covering the pre Great War period to enable further research, making the content of the book all the more important. Benjamin Palin Dobson was born in 1878 he joined the Brigade and served through the Great War. His family were owners of a large engineering company employing over 5,000 people in 1914, they were known as manufacturers of textile machinery and in 1914 one of the largest manufacturers of munitions in the region. He commanded the 53rd Brigade in 1920 and 1921. He owned a 30 ton steam yacht named ‘Jenny Jones’ and wrote several books, he died in 1936.

Lt Col, Tony Wingfield wrote a book titled ‘The Bolton Artillery A History 1860 – 1975’. The print run was 500 copies. He commanded 253 Regiment from 1st January 1950 to 23rd February 1953. A pre-war Territorial he had wartime service in the Regiment, was accepted to be a committee member of the BVAA and later became secretary serving in this capacity until his death in 1980.

Sales had commenced on 29th October 1976. An early copy had been accepted by Her Majesty the Queen as Captain General of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. The book is a general narrative covering the main events over time. He wrote two pages on the history from 1860 to 1914, explained the Brigades' involvements in the Great War in some detail, wrote a page on the interwar years and recorded the history of the 53rd and 111th in World War Two which takes up most of the book. He also explains the post war history of 253 Regiment and its headquarters, as well as the early years of ‘F’ Troop up to 1975.

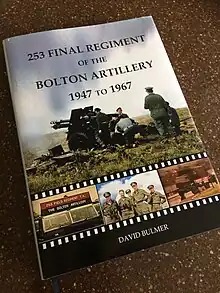

In 2023 a book titled ‘253 Final Regiment of the Bolton Artillery 1947 to 1967’ was published, written by David Bulmer a TA gunner officer from 1977 to 2001. Its content includes various aspects of the history of the Bolton Artillery. In Western Command, centred on Lancashire and Cheshire, 45 Artillery Regiments were established in 1947 on the reformation of the Territorial Army. Over the next two decades all would disappear. One of them was 253 (Bolton) Field Regiment RA TA. Described is its formation and activities year by year and how it weathered the highs and lows of the ever changing landscape of the reserves over the period. The story of the Bolton Artillery continued from its formation in 1967 in the ‘new’ TAVR as ‘F’ Troop 209 Battery (Manchester Artillery) 103 Regiment to 1970 set as an end point for the purpose of the book. Included is how 103 Regiment was established for the purpose of manning, training and equipping in the 6 months prior to its official start up on 1st April 1967. Also within its content is a description of the short lived TAVR 3 in which the Bolton Artillery contributed a Company, little has been written on this subject. The Bolton Artillery continues to this day as 216 Battery in the Army Reserve as part of 103 Regiment. Further chapters provide context and include the reformation of Territorial Army, drill halls, guns and vehicles, insignia and uniforms, biographies and appreciations of all Commanding Officers and Honorary Colonels and others associated. In addition a chapter on the history and heritage of the Bolton Volunteer Artillery Association (BVAA) is included and is described in detail for the first time. It was established in 1886 to support the welfare and financial needs of the Corps and Regiments of the Bolton Artillery and while not a military organisation it was run by its former and serving officers by committee and continues to do so today. A grant from it has enabled this book to be published. A chapter is included on the history of the Bolton Artillery bands first established in 1861 and how the Band of the Lancashire Artillery Volunteers was formed at Bolton in 1967, located there largely due to the strength and reputation of the 253 Regiment Band. Today it proudly continues from its Bolton base being the only Gunner band in the Army. The final part of the book contains three previously unpublished memoirs written by officers who served the Bolton Artillery as part of their own military histories. Col Mike Taylor CBE TD, Maj Chris Vere MBE TD, and Colonel Dennis Walton MC CBE TD. [136]

Memorials

The Bolton Artillery Memorial consists of a stone cenotaph standing in Nelson Square Gardens in Bolton. It lists 151 members of the Bolton Artillery who died during the First World War, many of whom were serving with other units at the time of their death. It lists another 151 names of those who died in the Second World War.[137][138] Two wooden panels listing 153 names for the First World War and another 153 for the Second World War are in the Army Reserve Centre at Nelson Street, Bolton, having originally been in the Bolton Artillery's drill hall at Silverwell Street.[139][140] Also at the Army Reserve Centre having been at the Silverwell Street drill hall are two framed rolls of honour listing the members of the Bolton Artillery's Sergeants' Mess who died in the First World War (9) and the Second World War (15).[141] A small plaque to the members of the Bolton Artillery who died in the two world wars was erected in St Peter's Church, Bolton, in 2003.[142]

Notes

- Frederick, p. 664.

- Lancashire Record Office Handlist 72

- Litchfield & Westlake, pp. 107–13.

- Beckett, p. 178.

- Litchfield & Westlake, p. 6.

- Army List, various dates.

- Beckett, pp. 247–53.

- London Gazette 20 March 1908.

- Frederick, pp. 677, 689.

- Litchfield, pp. 119–20.

- Becke, Pt 2a, pp. 35–41.

- 42nd (EL) Division at Long, Long Trail.

- Gibbon, pp. 3–5.

- Becke, Pt 2b, p. 6.

- WO Instructions Nos 108 & 310 of August 1914.

- Gibbon, p. 5.

- Farndale, Forgotten Fronts, pp. 2–8.

- Gibbon, pp. 6–16.

- Gibbon, p. 243.

- Aspinall-Oglander, pp. 392, 488.

- Farndale, Forgotten Fronts, pp. 21, 39, 54.

- Gibbon, pp. 16–22, 42–6.

- Aspinall-Oglander, pp. 168–9, 175-7.

- Aspinall-Oglander, p. 177.

- Gibbon, pp. 46–58.

- Aspinall-Oglander, pp. 466, 472–8.

- Becke, Pt 3a, p. 42.

- Farndale, Forgotten Fronts, pp. 57–8.

- Gibbon, pp. 59–62.

- Gibbon, pp. 63–4, 68.

- MacMunn & Falls, p. 156.

- Farndale, Forgotten Fronts, pp. 70–1.

- Gibbon, p. 69.

- Farndale, Forgotten Fronts, pp. 73–5.

- Gibbon, pp. 65–78.

- MacMunn & Falls, pp. 179–201.

- Gibbon, pp. 79–82.

- MacMunn & Falls, pp. 246–52.

- Farndale, Forgotten Fronts, pp. 77, 79, 81.

- Gibbon, pp. 82–5.

- Gibbon, pp. 86–8.

- 211 Bde RFA War Diary March 1917–March 1919, The National Archives (TNA), Kew, file WO 95/2649/2.

- 42nd DAC War Diary March 1917–March 1919, TNA file WO 95/2649/3.

- Gibbon, pp. 89–92.

- Becke, Pt 2b, pp. 20–1.

- Becke, Pt 3a, pp. 22–3.

- Gibbon, p. 95.

- Edmonds, 1917, Vol II, pp. 243–4.

- Farndale, Western Front, pp. 199–200, 205–10.

- Gibbon, pp. 96–104.

- Edmonds, 1917, Vol II, pp. 109–10.

- Gibbon, pp. 106–12.

- Gibbon, pp. 113–25.

- Edmonds, 1918, Vol I, pp. 392, 444–5, 481–7, 490–1, 521–2.

- Edmonds, 1918, Vol II, pp. 36–7, 42, 56, 134–5.

- Gibbon, pp. 126–41.

- Gibbon, pp. 142–53.

- Edmonds, 1918, Vol IV, pp. 188–92, 205–6, 228, 246, 250, 270.

- Farndale, Western Front, pp. 290–2.

- Gibbon, pp. 154–61.

- Edmonds, 1918, Vol IV, pp. 344–5, 362, 378, 380, 409–10, 420, 440, 449.

- Becke, Pt 2b, p. 47.

- Edmonds, 1918, Vol IV, pp. 420, 451–2, 469–7.

- Edmonds & Maxwell-Hyslop, pp. 43–4, 47–8, 117–8, Sketch 6.

- Gibbon, pp. 171–8.

- Edmonds & Maxwell-Hyslop, pp. 147–8, 151–2, 205, 240–1, 254, 335, 337–9, 364–6.

- Gibbon, pp. 179–87.

- Edmonds & Maxwell-Hyslop, pp. 481–3, 497, 503, 509–10, 523.

- Gibbon, pp. 191–7.

- Gibbon, pp. 200–2.

- Becke, Pt 2b, pp. 67–74.

- 66th (2nd EL) Division at Long, Long Trail.

- Becke, Pt 2b, Appendix 3.

- 332 AFA Bde War Diary February–April 1917, TNA file WO 95/3128/3.

- 66th DAC War Diary March 1917–May 1919, TNA file WO 95/3128/5.

- Frederick, pp. 489, 515.

- War Office, Titles & Designations, 1927.

- Sainsbury, pp. 15–7.

- Purcell & Gething.

- Frederick, p. 528.

- Sainsbury, pp. 17–20; Appendix 2.

- Western Command 3 September 1939 at Patriot Files.

- Farndale, Years of Defeat, p. 21.

- Joslen, p. 68.

- Joslen, p. 97.

- Ellis, France & Flanders, Chapter II.

- Farndale, Years of Defeat, p. 40.

- Ellis, France & Flanders, Chapter III.

- Ellis, France & Flanders, Chapter IV.

- Ellis, France & Flanders, Chapter XIII.

- Ellis, France & Flanders, Chapter XIV.

- Farndale, Years of Defeat, pp. 69, 83.

- Farndale, Years of Defeat, p. 102.

- Joslen, p. 99.

- Joslen, p. 570.

- Joslen, pp. 71–2, 485.

- Playfair & Molony, Vol IV, pp. 35, 92–3, 220.

- Joslen, p. 504.

- Joslen, p. 489.

- Playfair, Vol III, Appendix 6.

- Molony, Vol V, pp. 345–6, 433.

- Molony, Vol V, pp. 454–6, 459–61.

- Molony, Vol V, pp. 481–2, 485–90, Maps 28–9.

- Molony, Vol V, pp. 505–6.

- Molony, Vol V, p. 595.

- Molony, Vol VI, Pt I, pp. 10, 14, 76–9, 82–4, 99, 107–9, 120–2, 126, Map 7.

- Molony, Vol VI, Pt I, pp. 126, 201, 241–2, 247, 258–9, Map 16.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt II, pp. 5, 16–7, 28–9, 39, 46.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt II, pp. 89–93, 139–40, 152, 269, 348–9, 396–9, 418–21.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt III, pp. 30–1, 36, 42.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt III, pp. 126–9.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt III, pp. 222–5, 228, 262–7, 291, 293, 319.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt III, p. 324.

- Joslen, Pt VIII.

- Order of Battle of the Field Force in the United Kingdom, Part 3: Royal Artillery (Non-Divisional units), 22 October 1941, with amendments, TNA files WO 212/6 and WO 33/1883.

- Joslen, pp. 81, 569.

- Frederick, p. 519.

- Playfair & Molony, Vol IV, p. 337.

- Joslen, p. 467.

- Molony, Vol V, p. 490.

- Molony, Vol VI, Pt I, pp. 391–2, 407–8.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt II, pp. 334, 337–8.

- Joslen, p. 457.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt III, pp. 12–4.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt III, pp. 110–1.

- Jackson, Vol VI, Pt III, p. 112.

- Farndale, Annex M.

- Frederick, p. 997.

- Litchfield, Appendix 5.

- 235–265 Rgts RA at British Army 1945 on.

- Watson, TA 1947.

- Frederick, p. 1028.

- Frederick, pp. 1004, 1013.

- Frederick, p. 1039.

- Frederick, pp. 334, 1045.

- 253 Final Regiment of the Bolton Artillery 1947 to 1967, author David Bulmer

- IWM WMR Ref 3185.

- Bolton Artillery at Roll of Honour.

- IWM WMR Ref 10708.

- IWM WMR Ref 53324.

- IWM WMR Ref 86569.

- IWM WMR Ref 66895.

References

- C.F. Aspinall-Oglander, History of the Great War: Military Operations Gallipoli, Vol II, May 1915 to the Evacuation, London: Heinemann, 1932/Imperial War Museum & Battery Press, 1992, ISBN 0-89839-175-X/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84574-948-4.

- A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 2a: The Territorial Force Mounted Divisions and the 1st-Line Territorial Force Divisions (42–56), London: HM Stationery Office, 1935/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-39-8.

- A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 2b: The 2nd-Line Territorial Force Divisions (57th–69th), with the Home-Service Divisions (71st–73rd) and 74th and 75th Divisions, London: HM Stationery Office, 1937/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-39-8.

- A.F. Becke,History of the Great War: Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3a: New Army Divisions (9–26), London: HM Stationery Office, 1938/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2007, ISBN 1-847347-41-X.

- James E. Edmonds, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1917, Vol II, Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele), London: HM Stationery Office, 1948/Uckfield: Imperial War Museum and Naval and Military Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-845747-23-7.

- James E. Edmonds, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1918, Vol I, The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries, London: Macmillan, 1935/Imperial War Museum and Battery Press, 1995, ISBN 0-89839-219-5/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84574-725-1.

- James E. Edmonds, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1918, Vol II, March–April: Continuation of the German Offensives, London: Macmillan, 1937/Imperial War Museum and Battery Press, 1995, ISBN 1-87042394-1/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84574-726-8.

- James E. Edmonds, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1918, Vol IV, 8th August–26th September: The Franco-British Offensive, London: Macmillan, 1939/Uckfield: Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military, 2009, ISBN 978-1-845747-28-2.

- James E. Edmonds & Lt-Col R. Maxwell-Hyslop, History of the Great War: Military Operations, France and Belgium 1918, Vol V, 26th September–11th November, The Advance to Victory, London: HM Stationery Office, 1947/Imperial War Museum and Battery Press, 1993, ISBN 1-870423-06-2/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2021, ISBN 978-1-78331-624-3.

- Martin Farndale, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: Western Front 1914–18, Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institution, 1986, ISBN 1-870114-00-0.

- Martin Farndale, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: The Forgotten Fronts and the Home Base 1914–18, Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institution, 1988, ISBN 1-870114-05-1.

- Martin Farndale, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: The Years of Defeat: Europe and North Africa, 1939–1941, Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institution, 1988/London: Brasseys, 1996, ISBN 1-85753-080-2.

- J.B.M. Frederick, Lineage Book of British Land Forces 1660–1978, Vol I, Wakefield, Microform Academic, 1984, ISBN 1-85117-007-3.

- Frederick E. Gibbon, The 42nd East Lancashire Division 1914–1918, London: Country Life, 1920/Uckfield: Naval & Military Press, 2003, ISBN 1-84342-642-0.

- William Jackson, History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol VI: Victory in the Mediterranean, Part I|: June to October 1944, London: HM Stationery Office, 1987/Uckfield, Naval & Military Press, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-71-8.

- William Jackson, History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol VI: Victory in the Mediterranean, Part I|I: November 1944 to May 1945, London: HM Stationery Office, 1988/Uckfield, Naval & Military Press, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-72-6.

- Norman E.H. Litchfield, The Territorial Artillery 1908–1988 (Their Lineage, Uniforms and Badges), Nottingham: Sherwood Press, 1992, ISBN 0-9508205-2-0.

- Norman Litchfield & Ray Westlake, The Volunteer Artillery 1859–1908 (Their Lineage, Uniforms and Badges), Nottingham: Sherwood Press, 1982, ISBN 0-9508205-0-4.

- C.J.C. Molony, History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol V: The Campaign in Sicily 1943 and the Campaign in Italy 3rd September 1943 to 31st March 1944, London: HM Stationery Office, 1973/Uckfield, Naval & Military Press, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-69-6.

- C.J.C. Molony, History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol VI: Victory in the Mediterranean, Part I: 1st April to 4th June 1944, London: HM Stationery Office, 1987/Uckfield, Naval & Military Press, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-70-X.

- I.S.O. Playfair, History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol III: (September 1941 to September 1942) British Fortunes reach their Lowest Ebb, London: HM Stationery Office, 1960 /Uckfield, Naval & Military Press, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-67-X

- I.S.O. Playfair & Brig C.J.C. Molony, "History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series: The Mediterranean and Middle East, Vol IV: The Destruction of the Axis forces in Africa, London: HM Stationery Office, 1966/Uckfield, Naval & Military Press, 2004, ISBN 1-845740-68-8.

- Tim Purcell and Mike Gething, Wartime Wanderers: A Football Team at War, Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1996, ISBN 1-84018-583-X

- J.D. Sainsbury, The Hertfordshire Yeomanry Regiments, Royal Artillery, Part 1: The Field Regiments 1920-1946, Welwyn: Hertfordshire Yeomanry and Artillery Trust/Hart Books, 1999, ISBN 0-948527-05-6.

- War Office, Instructions Issued by The War Office During August 1914, London: HM Stationery Office.

- War Office, Titles and Designations of Formations and Units of the Territorial Army, London: War Office, 7 November 1927 (RA sections also summarised in Litchfield, Appendix IV).

External sources

- Chris Baker, The Long, Long Trail

- Bolton's Memories

- British Army units from 1945 on

- Imperial War Museum, War Memorials Register

- Lancashire Record Office, Handlist 72

- Orders of Battle at Patriot Files Archived 12 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Roll of Honour

- Graham Watson, The Territorial Army 1947