Boli (fetish)

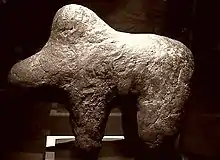

A boli (plural: boliw) is a fetish of the Bambara or Malinké of Mali.

Uses and customs

The boli can be zoomorphic (mostly a buffalo or a zebu) or even sometimes anthropomorphic. The populations of Mali who practice the so-called bamanaya cult, that is to say who indulge in the sacrifices of animals on the boliw and who communicate with the afterlife through masked dancers say they are Bamana.[1]

In the Mandingo religions a boli is an object said "charged", that is to say that by its magic it is able to accomplish extraordinary things, such as to give death, to guess the future, to take possession of someone, etc. The boli, which can also be made up of human or animal placenta, clay, tissue, skin, etc., is itself the symbol of the placenta.[2]

It is considered a living being and contains within it a core that can be either a stone, a metal or any other material. This nucleus or "grain" symbolizes the vital energy. The more blood the boli will receive, the more it will be "charged" with nyama (vital force).[3]

Theft of konos

In his book “L'Afrique fantôme” (The Phantom Africa), the anthropologist Michel Leiris recounts his adventure in the center of Africa, from west to east, between 1931 and 1933. A dozen scientists under the leadership of Marcel Griaule make up this expedition named Dakar-Djibouti mission. Its objectives are ethnographic and linguistic and consist essentially of collecting, on behalf of the Trocadéro museum, objects of African culture before it is destroyed by colonialism. Leiris reveals in his notes the unethical methods used to appropriate the coveted objects. One of the episodes that became famous is the theft of konos. Using pressure, manipulation, blackmail and threat of retaliation from the colonial administration, offering ridiculous compensation and sometimes committing night thefts, the ethnologists seize several konos from some Bambara villages, under the frightened and amazed eyes of the population. These thefts turn out to be highly sacrilegious gestures in the eyes of the Bambaras and in Leiris’s own words, constitute a “booty” and an “enormity”. He qualifies himself and his team as “demons or particularly powerful and daring bastards”.[4][5]

These konos will be successively exhibited at the Trocadéro museum, at the Museum of Mankind, at the Neuchâtel ethnography museum, among “one hundred masterpieces of the Museum of Mankind” in a New York museum as well as at the Quai Branly museum.[4]

References

- Jean-Paul Colleyn, Images, signes, fétiches. À propos de l’art bamana (Mali)

- Youssouf Cissé, The Dwarfs and the origin of the Hunting boli of the Malinke (Mali)

- Youssouf Cissé, La confrérie des chasseurs Malinké et Bambara: mythes, rites et récits initiatiques, Editions Nouvelles du Sud, 1994

- Etiembre, Yvan. "L'Homme qui déroba le kono en poursuivant un rêve d'Afrique. Michel Leiris". agoras.typepad.fr. Retrieved 2023-10-22.

- Leiris, Michel (2008). L' Afrique fantôme. Collection Tel (Nachdr. ed.). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-071188-8.

Bibliography

- Graham Harvey, The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, 2014, p.233.