Boiling-point elevation

Boiling-point elevation describes the phenomenon that the boiling point of a liquid (a solvent) will be higher when another compound is added, meaning that a solution has a higher boiling point than a pure solvent. This happens whenever a non-volatile solute, such as a salt, is added to a pure solvent, such as water. The boiling point can be measured accurately using an ebullioscope.

Explanation

The boiling point elevation is a colligative property, which means that it is dependent on the presence of dissolved particles and their number, but not their identity. It is an effect of the dilution of the solvent in the presence of a solute. It is a phenomenon that happens for all solutes in all solutions, even in ideal solutions, and does not depend on any specific solute–solvent interactions. The boiling point elevation happens both when the solute is an electrolyte, such as various salts, and a nonelectrolyte. In thermodynamic terms, the origin of the boiling point elevation is entropic and can be explained in terms of the vapor pressure or chemical potential of the solvent. In both cases, the explanation depends on the fact that many solutes are only present in the liquid phase and do not enter into the gas phase (except at extremely high temperatures).

Put in vapor pressure terms, a liquid boils at the temperature when its vapor pressure equals the surrounding pressure. For the solvent, the presence of the solute decreases its vapor pressure by dilution. A nonvolatile solute has a vapor pressure of zero, so the vapor pressure of the solution is less than the vapor pressure of the solvent. Thus, a higher temperature is needed for the vapor pressure to reach the surrounding pressure, and the boiling point is elevated.

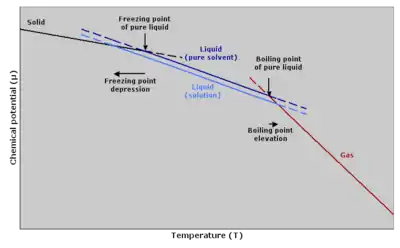

Put in chemical potential terms, at the boiling point, the liquid phase and the gas (or vapor) phase have the same chemical potential (or vapor pressure) meaning that they are energetically equivalent. The chemical potential is dependent on the temperature, and at other temperatures either the liquid or the gas phase has a lower chemical potential and is more energetically favorable than the other phase. This means that when a nonvolatile solute is added, the chemical potential of the solvent in the liquid phase is decreased by dilution, but the chemical potential of the solvent in the gas phase is not affected. This means in turn that the equilibrium between the liquid and gas phase is established at another temperature for a solution than a pure liquid, i.e., the boiling point is elevated.[1]

The phenomenon of freezing-point depression is analogous to boiling point elevation. However, the magnitude of the freezing point depression is larger than the boiling point elevation for the same solvent and the same concentration of a solute. Because of these two phenomena, the liquid range of a solvent is increased in the presence of a solute.

The equation for calculations at dilute concentration

The extent of boiling-point elevation can be calculated by applying Clausius–Clapeyron relation and Raoult's law together with the assumption of the non-volatility of the solute. The result is that in dilute ideal solutions, the extent of boiling-point elevation is directly proportional to the molal concentration (amount of substance per mass) of the solution according to the equation:[1]

- ΔTb = Kb · bc

where the boiling point elevation, is defined as Tb (solution) − Tb (pure solvent).

- Kb, the ebullioscopic constant, which is dependent on the properties of the solvent. It can be calculated as Kb = RTb2M/ΔHv, where R is the gas constant, and Tb is the boiling temperature of the pure solvent [in K], M is the molar mass of the solvent, and ΔHv is the heat of vaporization per mole of the solvent.

- bc is the colligative molality, calculated by taking dissociation into account since the boiling point elevation is a colligative property, dependent on the number of particles in solution. This is most easily done by using the van 't Hoff factor i as bc = bsolute · i, where bsolute is the molality of the solution.[2] The factor i accounts for the number of individual particles (typically ions) formed by a compound in solution. Examples:

- i = 1 for sugar in water

- i = 1.9 for sodium chloride in water, due to the near full dissociation of NaCl into Na+ and Cl− (often simplified as 2)

- i = 2.3 for calcium chloride in water, due to nearly full dissociation of CaCl2 into Ca2+ and 2Cl− (often simplified as 3)

Non integer i factors result from ion pairs in solution, which lower the effective number of particles in the solution.

Equation after including the van 't Hoff factor

- ΔTb = Kb · bsolute · i

At high concentrations, the above formula is less precise due to nonideality of the solution. If the solute is also volatile, one of the key assumptions used in deriving the formula is not true, since it derived for solutions of non-volatile solutes in a volatile solvent. In the case of volatile solutes it is more relevant to talk of a mixture of volatile compounds and the effect of the solute on the boiling point must be determined from the phase diagram of the mixture. In such cases, the mixture can sometimes have a boiling point that is lower than either of the pure components; a mixture with a minimum boiling point is a type of azeotrope.

Ebullioscopic constants

Values of the ebullioscopic constants Kb for selected solvents:[3]

| Compound | Boiling point in °C | Ebullioscopic constant Kb in units of [(°C·kg)/mol] or [°C/molal] |

|---|---|---|

| Acetic acid | 118.1 | 3.07 |

| Benzene | 80.1 | 2.53 |

| Carbon disulfide | 46.2 | 2.37 |

| Carbon tetrachloride | 76.8 | 4.95 |

| Naphthalene | 217.9 | 5.8 |

| Phenol | 181.75 | 3.04 |

| Water | 100 | 0.512 |

Uses

Together with the formula above, the boiling-point elevation can in principle be used to measure the degree of dissociation or the molar mass of the solute. This kind of measurement is called ebullioscopy (Latin-Greek "boiling-viewing"). However, since superheating is difficult to avoid, precise ΔTb measurements are difficult to carry out,[1] which was partly overcome by the invention of the Beckmann thermometer. Furthermore, the cryoscopic constant that determines freezing-point depression is larger than the ebullioscopic constant, and since the freezing point is often easier to measure with precision, it is more common to use cryoscopy.

See also

References

- P. W. Atkins, Physical Chemistry, 4th Ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1994, ISBN 0-19-269042-6, p. 222-225

- "Colligative Properties and Molality - UBC Wiki".

- P. W. Atkins, Physical Chemistry, 4th Ed., p. C17 (Table 7.2)