Military history of South Africa

The military history of South Africa chronicles a vast time period and complex events from the dawn of history until the present time. It covers civil wars and wars of aggression and of self-defence both within South Africa and against it. It includes the history of battles fought in the territories of modern South Africa in neighbouring territories, in both world wars and in modern international conflicts.

| Part of a series on the |

| Military history of South Africa |

|---|

| Conflicts |

| National Defence Force |

| Historical forces |

| Lists |

Prehistory

Before the arrival of any European settlers in South Africa the southern part of Africa was inhabited by the San people. As far as the military history of South Africa is concerned, African tribes frequently waged war against each other and made alliances for survival. The succession of Bantu immigrants from Central Africa during the time of the Bantu expansion initially led to the formation of merged tribes such as the Masarwa. After some time Bantu immigrants of greater strength invaded much of the traditional San territories. Archeological research suggests that each Bantu succession had better weapons than their predecessors enabling them to dominate the eastern parts of South Africa thereby forcing the Khoisan into less desirable parts of the country.[1]

In about the middle of the 18th Century, several clashes occurred between the Khoisan and the advancing Bantu tribes known as the Batlapin and the more powerful Barolong. These invaders would take as slaves those who had been conquered and referred to them as the Balala. During battle the defenders were armed with strong bows, and poisoned arrows; they also used the assegai and battle-axe, and protected their bodies with a small shield. In a fight in the open plain, they had little chance in defeating the invaders, though when attacked on a mountain or among rocks they managed to beat off their enemies.[1]

Khoikhoi-Dutch Wars

The arrival of the permanent settlements of Europeans, under the Dutch East India Company, at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652 brought them into the land of the local people, such as the Khoikhoi (called Hottentots by the Dutch), and the Bushmen (also known as the San), collectively referred to as the Khoisan.[2] While the Dutch traded with the Khoikhoi, nevertheless serious disputes broke out over land ownership and livestock. This resulted in attacks and counter-attacks by both sides which were known as the Khoikhoi–Dutch Wars that ended in the eventual defeat of the Khoikhoi. The First Khoikhoi-Dutch War took place from 1659 – 1660 and the second from 1673 – 1677.[3][4]

Anglo-Dutch rivalry

Castle of Good Hope

During 1664, tensions between England and the Netherlands rose with rumours of war being imminent – that same year, Commander Zacharias Wagenaer was instructed to build a pentagonal castle out of stone at 33.925806°S 18.427758°E. On 26 April 1679, the five bastions were built. The Castle of Good Hope is a fortification which was built on the original coastline of Table Bay and now, because of land reclamation, seems nearer the centre of Cape Town, South Africa. Built by the VOC between 1666 and 1679, the Castle is the oldest building in South Africa. The Castle acted as local headquarters for the South African Army in the Western Cape, but today houses the Castle Military Museum and ceremonial facilities for the traditional Cape Regiments.[5]

Battle of Muizenberg

The Battle of Muizenberg was a small but significant battle for the future destiny of South Africa which took place at Muizenberg (near Cape Town), South Africa in 1795; it led to the capture of the Cape Colony by the United Kingdom. A fleet of seven Royal Navy ships – five third-rates, Monarch (74), Victorious (74), Arrogant (74), America (64) and Stately (64), with the 16-gun sloops Echo and Rattlesnake – under Vice-Admiral Elphinstone anchored in Simon's Bay at the Cape of Good Hope in June 1795, having left England on 1 March. Their commander suggested to the Dutch governor that he place the Cape Colony under the protection of the British monarch – in effect, that he hand the colony over to Britain – which was refused. Simon's Town was occupied on 14 June by a force of 350 Royal Marines and 450 men of the 78th Highlanders, before the defenders could burn the town. Following skirmishes on 1 and 2 September, a final general attempt to recapture the camp was prepared by the Dutch for the 3rd, but at this point the British reinforcements arrived and the Dutch withdrew. A British advance on Cape Town, with the new reinforcements, began on the 14th; on the 16th, the colony capitulated.[6]: 300 [7]: 301 [8]: 302

The British assumed control of the Cape of Good Hope for the next seven years. The Cape was returned to the restored Dutch government (known as the Batavian Government) in 1804. In 1806 the British returned and after again defeating the Dutch at the Battle of Blaauwberg, stayed in control for more than 100 years.

Xhosa wars

The Xhosa Wars (also known as the Kaffir Wars or Cape Frontier Wars) were a series of nine wars between the Xhosa Kingdom, and the British Empire as well as European settlers with their Khoi allies, from 1779 and 1879 in what is now the Eastern Cape in South Africa. The Xhosa Kingdom was the first kingdom the British encountered in South Africa. The wars were responsible for the Xhosa people's loss of most of their land, and the incorporation of its people into European-controlled territories.[9]

Ndwandwe-Zulu War

The Ndwandwe-Zulu War of 1817–1819 was a war fought between the expanding Zulu kingdom and the Ndwandwe tribe in South Africa. Shaka revolutionised traditional ways of fighting by introducing the assegai to the northern bantus, a spear with a short shaft and broad blade, used as a close-quarters stabbing weapon. (Under Shaka's rule, losing an assegai was punishable by death. So it was never thrown like a javelin.) He also organised warriors into disciplined units known as Impis that fought in close formation behind large cowhide shields. In the Battle of Gqokli Hill in 1819, his troops and tactics prevailed over the superior numbers of the Ndwandwe people, who failed to destroy the Zulu in their first encounter.[10]

The Ndwandwe and the Zulus met again in combat at the Battle of Mhlatuze River in 1820. The Zulu tactics again prevailed, pressing their attack when the Ndwandwe army was divided during the crossing of the Mhlatuze River. Zulu warriors arrived at the Ndwande King Zwide's headquarters near present-day Nongoma before news of the defeat, and approached the camp singing Ndwandwe victory songs to gain entry. Zwide fled with some of his offspring including Madzanga. Most of the Ndwandwe abandoned their lands and migrated north and eastward. This was the start of the Mfecane, a catastrophic, bloody migration of many different tribes in the area, initially escaping the Zulus, but themselves causing their own havoc after adopting Zulu tactics in war. Shaka was the ultimate victor, and his (more peaceful) descendants still live today throughout Zululand, with customs and a way of life that can be easily traced to Shaka's day.

Mfecane

Mfecane (Zulu), also known as the Difaqane or Lifaqane (Sesotho), is an African expression which means something like "the crushing" or "scattering". It describes a period of widespread chaos and disturbance in southern Africa during the period between 1815 and about 1835.[11]

The Mfecane resulted from the rise to power of Shaka, the Zulu king and military leader who conquered the Nguni peoples between the Tugela and Pongola rivers in the beginning of the 19th century, and created a militaristic kingdom in the region. The Mfecane also led to the formation and consolidation of other groups – such as the Matabele, the Mfengu and the Makololo – and the creation of states such as the modern Lesotho.[12]

Battles between Voortrekkers and Zulus

The Battle of Italeni in what is now KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, in early 1838, between the Voortrekkers and the Zulus during the period of the Great Trek, resulted in the Zulu armies repulsing the Voortrekkers. On 9 April, near the Babanango Mountain Range a large Zulu impi (army) appeared, consisting of approximately 8,000 warriors. The Voortrekker commandos returned to their camp on 12 April. Boer general Piet Uys formed a raiding party of fifteen volunteers (including his son, Dirkie Uys.) During subsequent fighting Uys, his son, the Malan brothers as well as five of the volunteers were killed, and the Voortrekkers were forced to retreat. It has been speculated that, without the lessons learnt as a result of the Battle of Italeni – such as fighting from the shelter of ox-wagons whenever possible and choosing the place of battle rather than being enticed into unfavourable terrain – the Voortrekkers would not have succeeded in finally beating the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River eight months later.[13]

The Battle of Blood River (Afrikaans: Slag van Bloedrivier) was fought on 16 December 1838 on the banks of the Blood River (Bloedrivier) in what is today KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. In the aftermath of the Weenen massacre, a group of about 470 Voortrekkers, led by Andries Pretorius, defended a laager (circle of ox wagons) against Zulu impis, ruled by King Dingane and led by Dambuza (Nzobo) and Ndlela kaSompisi, numbering between 10 and 20 thousand. The Zulus repeatedly and unsuccessfully attacked the laager, until Pretorius ordered a group of horse riders to leave the encampment and engage the Zulus. Partly due to the fact that the Voortrekkers used rifles and at least one light cannon against the Zulus' spears, as well as the good location and motivation of the Voortrekkers, only three Voortrekkers were wounded and none perished; that contrasted against the more than 3,000 Zulu warriors who died.[14] The Voortrekkers credited God as the reason why they had won the battle as they had made a covenant asking for protection beforehand.[15]

The Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between Britain and the Zulus, and signalled the end of the Zulus as an independent nation. It was precipitated by Sir Bartle Frere High Commissioner for Southern Africa who manufactured a casus belli and prepared an invasion without the approval of Her Majesty's government.

At the Battle of Isandlwana (22 January 1879), the Zulu overwhelmed and wiped out 1,400 British soldiers. This battle is considered to be one of the greatest disasters in British colonial history. Isandlwana forced the policy makers in London to rally to the support of the pro-war contingent in the Natal government and commit whatever resources were needed to defeat the Zulu. The first invasion of Zululand ended with the catastrophe of Isandlwana where, along with heavy casualties, the main centre column lost all supplies, transport and ammunition and the British would be forced to halt their advances elsewhere while a new invasion was prepared. At Rorke's Drift (22–23 January 1879) 139 British soldiers successfully defended the station against an intense assault by four to five thousand Zulu warriors.

The Battle of Intombe was fought on 12 March 1879, between British and Zulu forces. The Siege of Eshowe took place during a three-pronged attack on the Impis of Cetshwayo at Ulundi. The Battle of Gingindlovu (uMgungundlovu) was fought between a British relief column sent to break the Siege of Eshowe and the Impis of Cetshwayo on 2 April 1879. The battle restored the British commanders' confidence in their army and their ability to defeat Zulu. With the last resistance removed, they were able to advance and relieve Eshowe. The Battle of Hlobane was a total disaster for the British; 15 officers and 110 men were killed, a further 8 wounded and 100 native soldiers died. The Battle of Kambula took place in 1879 when a Zulu army attacked the British camp at Kambula, resulting in a massive Zulu defeat. The Battle of Ulundi took place at the Zulu capital of Ulundi on 4 July 1879 and proved to be the decisive battle that finally broke the military power of the Zulu nation.

Boer Wars

First Anglo-Boer War

The First Boer War, also known as the First Anglo-Boer War or the Transvaal War, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 and was the first clash between the British and the South African Republic (Z.A.R.) Boers. It was precipitated by Sir Theophilus Shepstone, who annexed the South African Republic (Transvaal Republic) for the British in 1877. The British consolidated their power over most of the colonies of South Africa in 1879 after the Anglo-Zulu War, and attempted to impose an unpopular system of confederation on the region. The Boers protested, and in December 1880 they revolted. The battles of Bronkhorstspruit, Laing's Nek, Schuinshoogte, and Majuba Hill proved disastrous for the British where they found themselves outmaneuvered and outperformed by the highly mobile and skilled Boer marksmen. With the British commander-in-chief of Natal, George Pomeroy Colley, killed at Majuba, and British garrisons under siege across the entire Transvaal, the British were unwilling to further involve themselves in a war which was already seen as lost. As a result, William Gladstone's British government signed a truce on 6 March, and in the final peace treaty on 23 March 1881, gave the Boers self-government in the South African Republic (Transvaal) under a theoretical British oversight.

Jameson Raid

The Jameson Raid (29 December 1895 – 2 January 1896) was a raid on Paul Kruger's Transvaal Republic carried out by Leander Starr Jameson and his Rhodesian and Bechuanaland policemen over the New Year weekend of 1895–96. It was intended to trigger an uprising by the primarily British expatriate workers (known as Uitlanders, or in English "Foreigners") in the Transvaal but failed to do so. Though the raid was ineffective and no uprising took place, it did much to bring about the Second Boer War and the Second Matabele War.

The affair brought Anglo-Boer relations to a dangerous low, and the ill feeling was heightened by the "Kruger telegram" from the German Emperor, Wilhelm II. It congratulated Paul Kruger for defeating the raid, as well as appearing to recognise the Boer republic and offer support. The emperor was already perceived as anti-British, and a naval arms race had started between Germany and Britain. Consequently, the telegram alarmed and angered the British.

Second Anglo-Boer War

The Second Boer War, also known as the Second Anglo-Boer War, the Second Freedom War (Afrikaans) and referred to as the South African War in modern times took place from 11 October 1899 – 31 May 1902. The war was fought between Great Britain and the two independent Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (referred to as the Transvaal by the British). After a protracted hard-fought war, the two independent republics lost and were absorbed into the British Empire.

In all, the war resulted in around 75,000 deaths: 22,000 British and imperial soldiers (7,792 battle casualties, the rest through disease), 6,000–7,000 Boer Commandos, 20,000–28,000 Boer civilians, mostly women and children due to disease in concentration camps, and an estimated 20,000 black Africans living in the Boers republics who died in their own separate concentration camps. The last of the Boer holdouts surrendered in May 1902 and the war ended with the Treaty of Vereeniging in the same month. The war resulted in the creation of the Transvaal Colony which in 1910 was incorporated into the Union of South Africa. The treaty ended the existence of the South African Republic and the Orange Free State as Boer republics and placed them within the British Empire.

The Boers referred to the two wars as the Freedom Wars. Those Boers who wanted to continue the fight were known as "Bittereinders" (or irreconcilables) and at the end of the war a number like Deneys Reitz chose exile rather than sign an undertaking that they would abide by the peace terms. Over the following decade, many returned to South Africa and never signed the undertaking. Some, like Reitz, eventually reconciled themselves to the new status quo, but others waited for a suitable opportunity to restart the old quarrel. At the start of World War I the bitter-einders and their allies took part in a revolt known as the Maritz Rebellion.

World War I

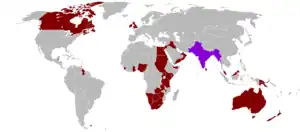

Bonds with the British Empire

The Union of South Africa, which came into being in 1910, tied closely to the British Empire, joined Great Britain and the allies against the German Empire. Prime Minister Louis Botha and Defence Minister Jan Smuts, both former Second Boer War generals who had fought against the British then, now became active and respected members of the Imperial War Cabinet. (See Jan Smuts during World War I.)

The Union Defence Force was part of significant military operations against Germany. In spite of Boer resistance at home, the Afrikaner-led government of Louis Botha joined the side of the Allies of World War I and fought alongside its armies. The South African Government agreed to the withdrawal of British Army units so that they were free to join the European war, and laid plans to invade German South-West Africa. Elements of the South African army refused to fight against the Germans and along with other opponents of the Government rose in open revolt. The government declared martial law on 14 October 1914, and forces loyal to the government under the command of General Louis Botha and Jan Smuts proceeded to destroy the Maritz Rebellion. The leading Boer rebels got off lightly with terms of imprisonment of six and seven years and heavy fines. (See World War I and the Maritz Rebellion.)

Military action against Germany during World War I

The Union Defence Force saw action in a number of places:

- It dispatched its army to German South-West Africa, later known as South West Africa, and now known as Namibia. The South Africans expelled German forces and gained control of the former German colony. (See German South-West Africa in World War I.)

- A military expedition under General Jan Smuts was dispatched to German East Africa (later known as Tanganyika) and now known as Tanzania. The objective was to fight German forces in that colony and to try to capture the elusive German General von Lettow-Vorbeck. Ultimately, Lettow-Vorbeck fought his tiny force out of German East Africa into Mozambique then Northern Rhodesia, where he accepted a cease-fire three days after the end of the war (see East African Campaign (World War I)).

- 1st South African Brigade troops were shipped to France to fight on the Western Front. The most costly battle that the South African forces on the Western Front fought in was the Battle of Delville Wood in 1916. (See South African Army in World War I and South African Overseas Expeditionary Force.)

- South Africans also saw action with the Cape Corps as part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in Palestine. (See Cape Corps 1915–1991)

Military contributions and casualties in World War I

More than 146,000 whites, 83,000 blacks and 2,500 people of mixed race ("Coloureds") and Indian South Africans served in South African military units during the war, including 43,000 in German South-West Africa and 30,000 on the Western Front. An estimated 3,000 South Africans also joined the Royal Flying Corps. The total South African casualties during the war was about 18,600 with over 12,452 killed – more than 4,600 in the European theatre alone. The Commonwealth War Graves commission has records of 9457 known South African War dead during World War I. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

There is no question that South Africa greatly assisted the Allies, and Great Britain in particular, in capturing the two German colonies of German South West Africa and German East Africa as well as in battles in Western Europe and the Middle East. South Africa's ports and harbours, such as at Cape Town, Durban, and Simon's Town, were also important rest-stops, refuelling-stations, and served as strategic assets to the British Royal Navy during the war, helping to keep the vital sea lanes to the British Raj open.

World War II

Political choices at outbreak of war

On the eve of World War II the Union of South Africa found itself in a unique political and military quandary. While it was closely allied with Great Britain, being a co-equal Dominion under the 1931 Statute of Westminster with its head of state being the British king, the South African Prime Minister on 1 September 1939 was none other than Barry Hertzog the leader of the pro-Afrikaner anti-British National party that had joined in a unity government as the United Party.

Hertzog's problem was that South Africa was constitutionally obligated to support Great Britain against Nazi Germany. The Polish-British Common Defence Pact obligated Britain, and in turn its dominions, to help Poland if attacked by the Nazis. After Hitler's forces attacked Poland in the morning of 1 September 1939, Britain declared war on Germany within a few days. A short but furious debate unfolded in South Africa, especially in the halls of power in the Parliament of South Africa, that pitted those who sought to enter the war on Britain's side, led by the pro-Allied pro-British Afrikaner and former prime minister Jan Smuts, and general against then-current prime minister Barry Hertzog, who wished to keep South Africa "neutral", if not pro-Axis.

Declaration of war against the Axis

On 4 September 1939, the United Party caucus refused to accept Hertzog's stance of neutrality in World War II and deposed him in favour of Smuts. Upon becoming Prime Minister of South Africa, Smuts declared South Africa officially at war with Germany and the Axis. Smuts immediately set about fortifying South Africa against any possible German sea invasion because of South Africa's global strategic importance controlling the long sea route around the Cape of Good Hope.

Smuts took severe action against the pro-Nazi South African Ossewabrandwag movement (they were caught committing acts of sabotage) and jailed its leaders for the duration of the war. (One of them, John Vorster, was to become future Prime Minister of South Africa.) (See Jan Smuts during World War II.)

Prime Minister and Field Marshal Smuts

Prime Minister Jan Smuts was the only important non-British general whose advice was constantly sought by Britain's wartime prime minister Winston Churchill. Smuts was invited to the Imperial War Cabinet in 1939 as the most senior South African in favour of war. On 28 May 1941, Smuts was appointed a field marshal of the British Army, becoming the first South African to hold that rank. Ultimately, Smuts would pay a steep political price for his closeness to the British establishment, to the King, and to Churchill, which had made Smuts very unpopular among the conservative nationalistic Afrikaners, leading to his eventual downfall, whereas most English-speaking whites and a minority of liberal Afrikaners in South Africa remained loyal to him. (See Jan Smuts during World War II.)

Military contributions in World War II

South Africa and its military forces contributed in many theatres of war. South Africa's contribution consisted mainly of supplying troops, airmen and material for the North African campaign (the Desert War) and the Italian Campaign as well as to Allied ships that docked at its crucial ports adjoining the Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean that converge at the tip of Southern Africa. Numerous volunteers also flew for the Royal Air Force. (See: South African Army in World War II; South African Air Force in World War II; South African Navy in World War II.)

- The South African Army and Air Force played a major role in defeating the Italian forces of Benito Mussolini during the 1940/1941 East African Campaign. The converted Junkers Ju 86s of 12 Squadron, South African Air Force, carried out the first bombing raid of the campaign on a concentration of tanks at Moyale at 8 am on 11 June 1940, mere hours after Italy's declaration of war.[16]: 37

- Another important victory that the South Africans participated in was the capture of Malagasy (now known as Madagascar) from the control of the Vichy French. British troops aided by South African soldiers, staged their attack from South Africa, landing on the strategic island on 4 May 1942[17]: 387 to preclude its seizure by the Japanese.

- The South African 1st Infantry Division took part in several actions in East Africa (1940) and North Africa (1941 and 1942), including the Battle of El Alamein, before being withdrawn to South Africa.

- The South African 2nd Infantry Division also took part in a number of actions in North Africa during 1942, but on 21 June 1942 two complete infantry brigades of the division as well as most of the supporting units were captured at the fall of Tobruk.

- The South African 3rd Infantry Division never took an active part in any battles but instead organised and trained the South African home defence forces, performed garrison duties and supplied replacements for the South African 1st Infantry Division and the South African 2nd Infantry Division. However, one of this division's constituent brigades – 7 SA Motorised Brigade – did take part in the invasion of Madagascar in 1942.

- The South African 6th Armoured Division fought in numerous actions in Italy from 1944 to 1945.

- The South African Air Force SAAF made a significant contribution to the air war in East Africa, North Africa, Sicily, Italy, the Balkans and even as far east as bombing missions aimed at the Romanian oilfields in Ploiești,[18]: 331 supply missions in support of the Warsaw uprising[18]: 246 and reconnaissance missions ahead of the Russian advances in the Lvov-Cracow area.[18]: 242

- Numerous South African airmen also volunteered service to the RAF, some serving with distinction.

- South Africa contributed to the war effort against Japan, supplying men and manning ships in naval engagements against the Japanese.[19]

Of the 334,000 men volunteered for full-time service in the South African Army during the war (including some 211,000 whites, 77,000 blacks and 46,000 "coloureds" and Asians), nearly 9,000 were killed in action.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission has records of 11,023 known South African war dead during World War II.[20]

However, not all South Africans supported the war effort. The Anglo-Boer war had ended only thirty five years earlier and to some, siding with the "enemy" was considered disloyal and unpatriotic. These sentiments gave rise to "The Ossewabrandwag" ("Oxwagon Sentinel"), originally created as a cultural organisation on the Centenary of the Great Trek becoming more militant and openly opposing South African entry into the war on side of the British. The organisation created a paramilitary group called Stormjaers ('storm chasers'), modelled on the Nazi SA or Sturmabteilung ("Storm Division") and which was linked to the German Intelligence (Abwehr) and the German Foreign Office (Dienstelle Ribbentrop) via Luitpold Werz – the former German Consul in Pretoria. The Stormjaers carried out a number of sabotage attacks against the Smuts government and actively tried to intimidate and discourage volunteers from joining the army recruitment programs.[21]

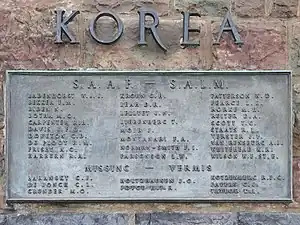

Korean War

In the Korean War, the 2 Squadron ("The Flying Cheetahs") took part as South Africa's contribution. It won many American decorations, including the honour of a United States Presidential Unit Citation in 1952:

- 2 Sqn had a long and distinguished record of service in Korea flying F-51D Mustangs and later F-86F Sabres. Their role was mainly flying ground attack and interdiction missions as one of the squadrons making up the USAF's 18th Fighter Bomber Wing.

- During the war the squadron flew a grand total of 12 067 sorties for a loss of 34 pilots and two other ranks. Aircraft losses amounted to 74 out of 97 Mustangs and four out of 22 Sabres. Pilots and men of the squadron received a total of 797 medals including 2 Silver Stars – the highest award to non-American nationals – 3 Legions of Merit, 55 Distinguished Flying Crosses and 40 Bronze Stars. 8 pilots became POW's. Casualties: 20 KIA 16 WIA.[22]

Some sources[23] list 35 deaths from 2 Squadron.

Simonstown Agreement

The Simonstown Agreement was a naval co-operation agreement between the United Kingdom and South Africa signed 30 June 1955. Under the agreement, the Royal Navy gave up its naval base at Simonstown, South Africa, and transferred command of the South African Navy to the government of South Africa. In return, South Africa promised the use of the Simonstown base to Royal Navy ships.

South Africa and Israel

U.S. Intelligence believed that Israel participated in South African nuclear research projects and supplied advanced non-nuclear weapons technology to South Africa during the 1970s, while South Africa was developing its own atomic bombs.[24][25][26] According to David Albright, writing for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, "Faced with sanctions, South Africa began to organize clandestine procurement networks in Europe and the United States, and it began a long, secret collaboration with Israel." although he goes on to say "A common question is whether Israel provided South Africa with weapons design assistance, although available evidence argues against significant cooperation."[27] According to the Nuclear Threat Initiative, in 1977 Israel traded 30 grams of tritium in exchange for 50 tons of South African uranium and in the mid-80s assisted with the development of the RSA-3 ballistic missile.[28] Also in 1977, according to foreign press reports, it was suspected that South Africa signed a pact with Israel that included the transfer of military technology and the manufacture of at least six atom bombs.[29]

Chris McGreal has claimed that "Israel provided expertise and technology that was central to South Africa's development of its nuclear bombs".[30] In 2000, Dieter Gerhardt, Soviet spy and a former commodore in the South African Navy, claimed that Israel agreed in 1974 to arm eight Jericho II missiles with "special warheads" for South Africa.[31]

South African undercover activity abroad

- On 4 October 1966, the Kingdom of Lesotho attained full independence, governed by a constitutional monarchy. In 1973, an appointed Interim National Assembly was established. With an overwhelming progovernment majority, it was largely the instrument of the BNP, led by Prime Minister Jonathan. South Africa had virtually closed the country's land borders because of Lesotho support of cross-border operations of the African National Congress (ANC). Moreover, South Africa publicly threatened to pursue more direct action against Lesotho if the Jonathan government did not root out the ANC presence in the country. This internal and external opposition to the government combined to produce violence and internal disorder in Lesotho that eventually led to a military takeover in 1986.

- In 1981, the Seychelles experienced a failed coup attempt by Mike Hoare and a team of mercenaries. An international commission, appointed by the UN Security Council in 1982, concluded that South African defence agencies had been involved in the attempted takeover, including supplying weapons and ammunition. See History of Seychelles.

- The South African army, and especially its air force, was actively involved in aiding the security forces in Rhodesia against Marxist insurgents led by the Patriotic Front.

South Africa and weapons of mass destruction

From the 1960s to the 1990s, South Africa pursued research into weapons of mass destruction, including nuclear,[32] biological, and chemical weapons under the Apartheid regime. Six nuclear weapons were assembled.[33]

South African strategy was, if political and military instability in Southern Africa became unmanageable, to conduct a nuclear weapon test in a location such as the Kalahari desert, where an underground testing site had been prepared, to demonstrate its capability and resolve—and thereby highlight the peril of intensified conflict in the region—and then invite a larger power such as the United States to intervene.

Before the anticipated changeover to a majority-elected African National Congress–led government in the 1990s, the South African government dismantled all of its nuclear weapons, the first state in the world which voluntarily gave up all nuclear arms it had developed itself. The country has been a signatory of the Biological Weapons Convention since 1975, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons since 1991, and the Chemical Weapons Convention since 1995. In February 2019, South Africa ratified the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, becoming the first country to have had nuclear weapons, disarmed them and gone on to sign the treaty.

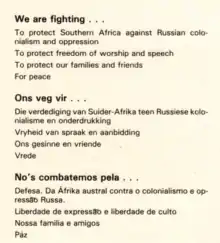

South African Border War

Between 1966 and 1989, South Africa waged a long and bitter counter-insurgency campaign against the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) in South-West Africa.[34] PLAN was backed by the Soviet Union and a number of Warsaw Pact member states, as well as several sympathetic, newly independent African governments.[35] It also received considerable combat support from the People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) and a sizeable contingent of Cuban military advisors.[36] In response, South Africa underwent a massive military expansion to combat the PLAN threat, which included the formation of several elite special forces units such as Koevoet, 32 Battalion, and the Reconnaissance Commando Regiment.[37] South African troops raided neighbouring states to strike at PLAN forward operating bases, which occasionally entailed clashes with FAPLA[38] and the Zambian Defence Force.[39] This largely undeclared conflict became known as the South African Border War during the late 1970s.[40]

SADF expeditionary forces targeted guerrilla bases, refugees, and rural infrastructure in Angola and Zambia, depending initially on border raids, patrols, and air strikes to keep PLAN at bay.[41] This was eventually extended to a permanent SADF military presence throughout southern Angola, with the objective of forcing PLAN bases to relocate further and further north.[40] While this strategy was successful, it resulted in the parallel expansion of FAPLA, with Soviet assistance, to meet what Luanda perceived as a direct South African threat to Angolan sovereignty.[41] FAPLA and the SADF clashed continuously between 1981 and 1984, and again from 1987 to 1988, culminating in the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale.[38]

The South African Border War was closely linked to the Angolan Civil War. South African expeditionary units had openly invaded Angola in 1975 during Operation Savannah, an ill-fated attempt to support two rival Angolan factions, the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA), during the civil war. The SADF was forced to withdraw under overwhelming pressure from thousands of Cuban combat troops.[42] When South Africa began intensifying its campaign against PLAN in the 1980s, it reasserted its alliance with UNITA and took the opportunity to bolster that movement with training and captured PLAN weaponry.[43]

The Battle of Cuito Cuanavale proved to be a major turning point for both conflicts, as it resulted in the Angolan Tripartite Accord, in which Cuba pledged to withdraw its troops from Angola while South Africa withdrew from South-West Africa.[44] South-West Africa received independence as the Republic of Namibia in 1990.[45]

Production of military equipment by South Africa

South Africa has produced a variety of significant weapons, vehicles and planes for its own uses as well as for international export. Some have been established weapons produced under licence and in other instances South Africa has innovated and manufactured its own weapons and vehicles. The predominant manufacturer of weapons is Denel.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Armscor produced a great deal of South Africa's armament as South Africa was under UN sanctions. It was during this time that Armscor contracted with Gerald Bull's Space Research Corporation for advanced 155mm howitzer designs, which it eventually produced, used, and exported to countries such as Iraq.

Internal guerrilla activity during apartheid

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, it was common for anti-apartheid political movements to form military wings, such as Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), which was created by the African National Congress, and the Azanian People's Liberation Army (APLA) of the Pan-Africanist Congress.[46] These functioned as de facto guerrilla armies, carrying out acts of sabotage and waging a limited rural insurgency.[47] The guerrillas occasionally clashed with each other as their respective political organs jockeyed for internal influence.[48]

Though fought on a much smaller scale than the South African Border War, the SADF's operations against MK and APLA mirrored several important aspects of that conflict. Much like PLAN, for example, MK often sought sanctuary in states adjacent to South Africa's borders.[41] The SADF retaliated with targeted assassinations of MK personnel on foreign soil, and a combination of air strikes and special forces raids on MK bases in Zambia, Mozambique, Botswana, and Lesotho.[41]

Both MK and APLA were disbanded and integrated with the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) following the abolition of apartheid.[49]

Modern Afrikaner separatist militias

The Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) – "Afrikaner Resistance Movement" – was formed in 1973 in Heidelberg, Transvaal, a town southeast of Johannesburg. It is a political and paramilitary group in South Africa and was under the leadership of Eugène Terre'Blanche. They are committed to the restoration of an independent Afrikaner republic or "Boerestaat" within South Africa. In their heyday, the period of transition in the early 1990s, they received much publicity both in South Africa and abroad as an extremist white supremacist group.

During the Negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa, the AWB stormed the venue, the Kempton Park World Trade Centre, breaking through the glass front of the building with an armoured car. The invaders took over the main conference hall, threatening delegates and painting slogans on the walls and left again after a short period. In 1994, before the advent of majority rule, the AWB again gained international notoriety in its attempt to defend the dictatorial government of Lucas Mangope in the homeland of Bophuthatswana, who opposed the upcoming elections and the dissolution of "his" homeland. The AWB, along with a contingent of about 90 Afrikaner Volksfront militiamen entered the capital of Mmabatho on 10 and 11 March. Terre'Blanche was sentenced for the attempted murder of security guard, Paul Motshabi, but he only served three years. In June 2004, he was released from prison. Terre'blanche claimed that while in prison, he re-discovered God and has dropped some of his more violent and racist policies. He preached reconciliation as 'prescribed by God' in his later years. Terre'Blanche was murdered on his farm on 3 April 2010.

Present military: South African National Defence Force

The South African National Defence Force (SANDF) is the name of the present-day armed forces of South Africa. The military as it exists today was created in 1994, following South Africa's first post-apartheid national elections and the adoption of a new constitution. It replaced the South African Defence Force (SADF), and included personnel and equipment from the SADF and the former Homelands forces (Transkei, Venda, Bophuthatswana, and Ciskei), as well as personnel from the former guerrilla forces of some of the political parties involved in South Africa, such as the African National Congress's Umkhonto we Sizwe, the Pan Africanist Congress's APLA and the Self-Protection Units of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).

As of 2004, the integration process was considered complete, with the integrated personnel having been incorporated into a slightly modified structure very similar to that of the SADF, with the latter's structure and equipment for the most part being retained.

The commander of the SANDF is appointed by the President from one of the armed services. The current commander is General Solly Shoke. He in turn is accountable to the Minister of Defence, currently Nosiviwe Noluthando Mapisa-Nqakula.

Some of the Traditional South African Regiments have been serving the country for over a hundred and fifty years under various iterations of political systems and different governments.

Arms Deal

The South African Department of Defence's Strategic Defence Acquisition (known as the Arms Deal) aimed to modernise its defence equipment, which included the purchase of corvettes, submarines, light utility helicopters, lead-in fighter trainers and advanced light fighter aircraft. This saw the SANDF being provided with modern equipment.

Peacekeeping

Recent peacekeeping actions by the South African military include the South African intervention in Lesotho[lower-alpha 1] in order to restore the democratically elected government after a coup, as well as extensive contributions to the United Nations peacekeeping operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Burundi. An operation to Sudan has recently begun and is scheduled to be increased to Brigade strength.

Issues that face the SANDF include a severe shortage of pilots and naval combat officers, due to the replacement of white officers from the former SADF with appointments from the old liberation forces and emigration. The loss of trained personnel and the decommissioning of much needed equipment due to funding issues, high HIV-rates amongst personnel and the fact that SANDF infantry soldiers are some of the oldest in the world, all raise questions regarding the current fighting efficiency of the SANDF. Some of these issues are being addressed with the introduction of the Military Skills Development (MSD) programme, as well as aggressive recruitment and training by the Reserve Force Regiments.

Recently, the SANDF has been involved in combat in both the Central African Republic (Bangui) as well as in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FIB)). The performance of the SANDF soldiers in combat in these two theatres has gone a long way towards silencing critics of the combat effectiveness of the actual soldiers but has refocused the debate on that of the political leadership as well as the procurement and recruitment issues that still abound.

Four armed services make up the forces of the SANDF:

See also

- List of wars involving South Africa

- British logistics in the Boer War

- List of conflicts in Africa

- Permanent Force

- South African Air Force

- South African Air Force Museum

- South African Army

- South African Defence Force (1957–1994)

- South African National Museum of Military History

- South African National Defence Force (1994–present)

- South African Navy

- South African Police Service

- South African resistance to war

Notes

- Operation BOLEAS

References

- Ethnography and Condition of South Africa Before A.D. 1505, George McCall Theal, London 1919.

- "What to Know About the Khoisan, South Africa's First People". the culture trip. 20 February 2018.

- "Chronology of the 1600s at the Cape". sahistory.org.za. 21 November 2006. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 3, A short chronicle of warfare in South Africa, compiled by the Military Information Bureau, Page 40

- "Castle of Good Hope". castleofgoodhope.co.za. 20 November 2006.

- "Colonial Expeditions – East Indies". Naval History of Great Britain, Vol. I. p. 300. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- "Capture of the Cape of Good Hope". Naval History of Great Britain, Vol. I. p. 301. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- "Colonial Expeditions – East Indies". Naval History of Great Britain, Vol. I. p. 302. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- "Summary of the Boer-Xhosa Wars". Lecture on Southern Africa 1800–1875. 20 November 2006. Archived from the original on 4 September 2006.

- "Zulu Civil War – Shaka Zulu". eshowe.com. 20 November 2006. Archived from the original on 14 January 2007.

- "Background to the Mfecane". countrystudies.us/south-africa U.S. Library of Congress. 20 November 2006.

- "Zulu Rise & Mfecane". bbc.co.uk The Story of Africa. 20 November 2006.

- "The Battle of Italeni". The South African Military History Society: Military History Journal – Vol 4 No 5. 20 November 2006.

- "This Day in History: 16 December 1838". sahistory.org.za/pages/chronology. 20 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 April 2006.

- "Boers believed their God won the Battle of Blood River". Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- Brown, J.A. (1970). A Gathering of Eagles: The Campaigns of the South African Air Force in Italian East Africa 1940–1941. Cape Town: Purnell.

- Brown, J.A. (1974). Eagles Strike: Campaigns of the South African Air Force in Egypt, Cyrenaica, Libya, Tunisia, Tripolitana and Madagascar 1941–1943. Cape Town: Purnell.

- Orpen, N.; Martin, H.J. (1977). Eagles Victorious. Cape Town: Purnell.

- "South Africa and the War against Japan 1941–1945". South African Military History Society (Military History Journal – Vol 10 No 3). 21 November 2006.

- "Commonwealth War Graves Commission". cwgc.org. 1 March 2007.

- Martin, H. J. Lt-Gen; Orpen, Neil D Col (1979). South Africa at War: Military and Industrial Organisation and Operations in connection with the conduct of war: 1939–1945. Vol. South African Forces in World War II: Volume VII. Cape Town: Purnell. p. 25. ISBN 0-86843-025-0.

- "South Africa in the Korean War". korean-war.com. 20 November 2006. Archived from the original on 1 November 2006.

- Dovey, John. "SA Roll of Honour: List People: Korea". ROH Database. Just Done Productions Publishing. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Von Wielligh, Nic; von Wielligh-Steyn, Lydia (2015). The Bomb – South Africa's Nuclear Weapons Programme (Illustrated ed.). Pretoria: Litera. ISBN 9781920188481.

- "The 22 September 1979 Event" (PDF). Interagency Intelligence Memorandum. National Security Archive. December 1979. p. 10 (paragraph 30). MORI DocID: 1108245. Retrieved 1 November 2006.

- Aftergood, Steven; Garbose, Jonathan. "RSA Nuclear Weapons Program". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- Albright, David (July 1994). "South Africa and the affordable bomb". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc. 50 (4): 37–47. Bibcode:1994BuAtS..50d..37A. doi:10.1080/00963402.1994.11456538. ISSN 0096-3402. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

- "South Africa Nuclear Overview". Nuclear Threat Initiative. 28 September 2015.

- Mizroch, Amir (2 November 2006). "Late SA president P.W. Botha felt Israel had betrayed him". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- McGreal, Chris (7 February 2006). "Brothers in arms – Israel's secret pact with Pretoria". The Guardian.

- "Tracking Nuclear Proliferation". PBS Newshour. 2 May 2005. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Von Wielligh, Nic (2015). The bomb : South Africa's nuclear weapons programme (First English ed.). Pretoria: Litera Publications; Translation edition (July 27, 2016). ISBN 9781920188481.

- "Nuclear Weapons Program". www.globalsecurity.org.

- André Wessels, "The war for Southern Africa (1966–1989) that continues to fascinate and haunt us." Historia 62.1 (2017): 73–91. online

- Hooper, Jim (2013) [1988]. Koevoet! Experiencing South Africa's Deadly Bush War. Solihull: Helion and Company. pp. 86–93. ISBN 978-1868121670.

- Clayton, Anthony (1999). Frontiersmen: Warfare in Africa since 1950. Philadelphia: UCL Press, Limited. pp. 120–24. ISBN 978-1857285253.

- Stapleton, Timothy (2013). A Military History of Africa. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 251–57. ISBN 978-0313395703.

- Jacklyn Cock, Laurie Nathan (1989). War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa. New Africa Books. pp. 124–276. ISBN 978-0-86486-115-3.

- Steenkamp, Willem (2006). Borderstrike! South Africa into Angola 1975–1980 (2006 ed.). Just Done Productions. pp. 132–226. ISBN 978-1920169008.

- Baines, Gary (2014). South Africa's 'Border War': Contested Narratives and Conflicting Memories. London: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 1–4, 138–40. ISBN 978-1472509710.

- Minter, William (1994). Apartheid's Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. pp. 114–117. ISBN 978-1439216187.

- George, Edward (2005). The Cuban intervention in Angola. New York: Frank Cass Publishers. pp. 105–06. ISBN 978-0415647106.

- Weigert, Stephen (2011). Angola: A Modern Military History. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0230117778.

- Harris, Geoff (1999). Recovery from Armed Conflict in Developing Countries: An Economic and Political Analysis. Oxfordshire: Routledge Books. pp. 262–64. ISBN 978-0415193795.

- Hampson, Fen Osler (1996). Nurturing Peace: Why Peace Settlements Succeed Or Fail. Stanford: United States Institute of Peace Press. pp. 53–70. ISBN 978-1878379573.

- Gibson, Nigel; Alexander, Amanda; Mngxitama, Andile (2008). Biko Lives! Contesting the Legacies of Steve Biko. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 138. ISBN 978-0230606494.

- Switzer, Les (2000). South Africa's Resistance Press: Alternative Voices in the Last Generation Under Apartheid. Issue 74 of Research in international studies: Africa series. Ohio University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780896802131.

- Mitchell, Thomas (2008). Native vs Settler: Ethnic Conflict in Israel/Palestine, Northern Ireland and South Africa. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 194–96. ISBN 978-0313313578.

- "Final Integration Report: SANDF briefing | Parliament of South Africa monitored". Pmg.org.za. 9 November 2004. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

Sources

- South Africa. Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia 2009. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009.

Further reading

- Liebenberg, Ian (Fall 1997). "The integration of the military in post-liberation South Africa: The contribution of revolutionary armies". Armed Forces & Society. Sage Publications, Inc. 24 (1): 105–132. doi:10.1177/0095327X9702400105. JSTOR 45347233. S2CID 145284963.

- Seegers, Annette (15 May 1996). The military in the making of modern South Africa. IB Tauris. ISBN 978-1850436898.

- Stapleton, Timothy J. (9 April 2010). A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid. Praeger. ISBN 978-0313365898.

- Wessels, André (9 January 2018). "The war for Southern Africa (1966–1989) that continues to fascinate and haunt us". Southern Journal for Contemporary History. 42 (2): 24–47. doi:10.18820/24150509/JCH42.v2.2.