Boeing 737 MAX certification

The Boeing 737 MAX was initially certified in 2017 by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Global regulators grounded the plane in 2019 following fatal crashes of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. Both crashes were linked to the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), a new automatic flight control feature. Investigations in both crashes determined that Boeing and the FAA favored cost-saving solutions, but ultimately produced a flawed design of the MCAS instead.[1] The FAA's Organization Designation Authorization program, allowing manufacturers to act on its behalf, was also questioned for weakening its oversight of Boeing.

.jpg.webp)

Boeing wanted the FAA to certify the airplane as another version of the long-established 737; this would limit the need for additional training of pilots, a major cost saving for airline customers. During flight tests, however, Boeing discovered that the position and larger size of the engines tended to push up the airplane nose during certain maneuvers. To counter that tendency and ensure fleet commonality with the 737 family, Boeing added MCAS so the MAX would handle similar to earlier 737 versions. Boeing convinced the FAA that MCAS could not fail hazardously or catastrophically, and that existing procedures were effective in dealing with malfunctions. The MAX was exempted from certain newer safety requirements, saving Boeing billions of dollars in development costs.[2] In February 2020, the US Justice Department (DOJ) investigated Boeing's hiding of information from the FAA, based on the content of internal emails.[3] In January 2021, Boeing settled to pay over $2.5 billion after being charged with fraud in connections to the crashes.

In June 2020, the U.S. Inspector General's report revealed that MCAS problems dated several years before the accidents.[4] The FAA found several defects that Boeing deferred to fix, in violation of regulations.[5] In September 2020, the House of Representatives concluded its investigation and cited numerous instances where Boeing dismissed employee concerns with MCAS, prioritized deadline and budget constraints over safety, and where it lacked transparency in disclosing essential information to the FAA. It further found that the assumption that simulator training would not be necessary had "diminished safety, minimized the value of pilot training, and inhibited technical design improvements".[6]

In November 2020, the FAA announced that it had cleared the 737 MAX to return to service.[7] Various system, maintenance and training requirements are stipulated, as well as design changes that must be implemented on each aircraft before the FAA issues an airworthiness certificate, without delegation to Boeing. Other major regulators worldwide are gradually following suit: In 2021, after two years of grounding, Transport Canada and EASA both cleared the MAX subject to additional requirements.[8][9]

Initial certification

The first flight took place on January 29, 2016, at Renton Municipal Airport,[10] nearly 49 years after the maiden flight of the original 737-100, on April 9, 1967.[11] The first MAX 8, 1A001, was used for aerodynamic trials: flutter testing, stability and control, and takeoff performance-data verification, before it was modified for an operator and delivered. 1A002 was used for performance and engine testing: climb and landing performance, crosswind, noise, cold weather, high altitude, fuel burn and water-ingestion. Aircraft systems including autoland were tested with 1A003. 1A004, with an airliner layout, flew function-and-reliability certification for 300 hours with a light flight-test instrumentation.[12]

The 737 MAX gained FAA certification on March 8, 2017,[13][14] and in the same month was approved by EASA on March 27, 2017.[15] After completing 2,000 test flight hours and 180-minute ETOPS testing requiring 3,000 simulated flight cycles in April 2017, CFM International notified Boeing of a possible manufacturing quality issue with low pressure turbine (LPT) discs in LEAP-1B engines.[16] Boeing suspended 737 MAX flights on May 4,[17] and resumed flights on May 12.[18]

During the certification process, the FAA delegated many evaluations to Boeing, allowing the manufacturer to review their own product.[10][19] It was widely reported that Boeing pushed to expedite approval of the 737 MAX to compete with the Airbus A320neo, which hit the market nine months ahead of Boeing's model.[20]

Type rating

In the U.S., the MAX shares a compatible type rating throughout the Boeing 737 series.[21] The impetus for Boeing to build the 737 MAX was serious competition from the Airbus A320neo, which was a threat to win a major order for aircraft from American Airlines, a traditional customer for Boeing airplanes.[22] Boeing decided to update its 737, designed in the 1960s, rather than designing a clean sheet aircraft, which would have cost much more and taken years longer. Boeing's goal was to ensure the 737 MAX would not need a new type rating, which would require significant additional pilot training, adding unacceptably to the overall cost of the airplane for customers.

The 737 was first certified by the FAA in 1967. Like every new 737 model since then, the MAX has been approved partially with the original requirements and partially with more current regulations, enabling certain rules and requirements to be grandfathered in.[23] Chief executive Dai Whittingham of the independent trade group UK Flight Safety Committee disputed the idea that the MAX was just another 737, saying, "It is a different body and aircraft but certifiers gave it the same type rating."[24]

On May 15, 2019, during a senate hearing, FAA acting administrator Daniel Elwell defended their certification process of Boeing aircraft. Nonetheless, the FAA criticized Boeing for not mentioning the MCAS in the 737 MAX's manuals.[25][26]

Crew manuals

Boeing considered MCAS part of the flight control system, based on the fundamental design philosophy of retaining commonality with the 737NG.[22] In 2013, a Boeing meeting urged participants to consider MCAS (Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System) as a simple add-on to the existing stability function: "If we emphasize MCAS is a new function there may be greater certification and training impact".[27] Boeing also played down the scope of MCAS to regulators. The company "never disclosed the revamp of MCAS to FAA officials involved in determining pilot training needs".[28]

On March 30, 2016, Mark Forkner, then MAX's chief technical pilot, requested senior FAA officials to remove MCAS from the pilot's manual. Boeing had presented MCAS as being existing technology, but inquiries and certification authorities have raised doubts about its technology readiness. The officials had been briefed on the original version of MCAS but not that MCAS was being significantly overhauled.[28] Because Boeing offered Southwest Airlines a $1-million-per-plane rebate if training was ultimately required, pressure on Boeing executives and engineers increased.

In 2017, as the airliner's five-year certification was nearly completed, Forkner wrote to an FAA official, "Delete MCAS".[29] He then departed Boeing and joined Southwest Airlines in 2018.[30] MCAS was left in the glossary of the 1,600-page flight manual.[31]

Top Boeing officials believed MCAS operated only far beyond the normal flight envelope, and was unlikely to activate in normal flight.[32] Boeing had also failed to answer questions raised by Canadian test pilots on behalf of Transport Canada about how the anti-stall system operated before the airplane was certified.[33]

Most air regulatory agencies, including the FAA, Transport Canada and EASA, did not require specific training on MCAS. Brazil's national civil aviation agency "was one of the only civil aviation authorities to require specific training for the operation of the 737-8 Max".[34] Pilots of the 737 Next Generation received an hour-long iPad lesson to fly on the MAX.[35]

On November 6, 2018, after the Lion Air accident, Boeing published a service bulletin in which MCAS was mentioned as a "pitch trim system." In reference to the Lion Air accident, Boeing said the system could be triggered by erroneous angle of attack information when the aircraft is under manual control, and reminded pilots of various indications and effects that can result from this erroneous information.[36][37] Only four days later, on November 10, 2018, Boeing acknowledged the existence of MCAS in a message to operators.[38][39]

From November 2018 to March 2019, months between the accidents, the FAA Aviation Safety Reporting System received numerous U.S. pilot complaints of the aircraft's unexpected behaviors, and how the crew manual lacked any description of the system.[40]

On January 9, 2020, Boeing turned over a hundred internal messages of employees criticizing the FAA and the 737 MAX's development. The majority of them being made before either crash. Some messages read that Boeing was trying to get airlines and regulators, including Lion Air,[41] to avoid simulator training, as well as general frustration with Boeing management.[42]

The FAA stated that "the tone and content of some of the language contained in the documents is disappointing," while Boeing said that the messages "do not reflect the company we are and need to be, and they are completely unacceptable."[43][44]

Simulator training

On May 17, 2019, after discovering 737 MAX flight simulators could not adequately replicate MCAS activation,[45] Boeing corrected the software to improve the force feedback of the manual trim wheel and to ensure realism.[46] This led to a debate on whether simulator training is a prerequisite prior to the aircraft's eventual return to service. On May 31, Boeing proposed that simulator training for pilots flying on the 737 MAX would not be mandatory.[47] Computer training is deemed sufficient by the FAA Flight Standardization Board, the US Airline Pilots Association and Southwest Airlines pilots, but Transport Canada and American Airlines urged use of simulators.[48][49]

On June 19, in a testimony before the U.S. House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Chesley Sullenberger advocated for simulator training. "Pilots need to have first-hand experience with the crash scenarios and its conflicting indications before flying with passengers and crew."[50][51] The "differences training" is the subject of worry by senior industry training experts.[52] Textron-owned simulator maker TRU Simulation + Training anticipated a transition course but not mandatory simulator sessions in minimum standards being developed by Boeing and the FAA.[53]

On July 24, Boeing indicated that some regulatory agencies may mandate simulator training before return to service, and also expected some airlines to require simulator sessions even if these are not mandated.[54]

On August 22, 2019, the FAA announced that it would invite pilots from around the world, intended to be a representative cross-section of "ordinary" 737 pilots, to participate in simulator tests as part of the recertification process, at a date to be determined.[55] The evaluation group sessions are one of the final steps in the validation of flight-control computer software updates and will involve around 30 pilots, including some first officers with multi-crew pilot licenses that emphasize simulator experience rather than flight hours. The FAA hopes that the feedback from pilots with more varied experience will enable it to determine more effective training standards for the aircraft.[56]

On January 7, 2020, Boeing reversed its position and now recommends that pilots receive training in a MAX flight simulator. The FAA will conduct tests using pilots from US and foreign airlines, to determine flight training and emergency procedures. National aviation authorities will consider Boeing's recommendation but will also rely on the outcome of tests and expert opinions.[57][58] According to The Seattle Times as of this policy reversal, only 34 full-motion 737 MAX flight simulators have been deployed worldwide.[59] The FAA agrees with Boeing on requiring simulator training for pilots, as the MAX returns to service.[60]

Rejected improvements

During the development of the MAX, some systems that could have improved situation awareness related to the accidents did not make it. Boeing also successfully appealed safety concerns raised by FAA safety specialists about the separation of cables into different zones of the aircraft, to avoid failures due to a common cause. The appeal raised doubts about the independence of the FAA.[61]

According to The Seattle Times, Boeing convinced the FAA, during MAX certification in 2014, to grant exceptions to federal crew alerting regulations, specifically relating to the "suppression of false, unnecessary" information.[62] DeFazio, Chair of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, said that Boeing considered adding a more robust alerting system for MCAS but finally shelved the idea.[63] FAA exempted Boeing from installing an Engine Indicating and Crew Alerting System (EICAS).[64]

In a draft report, the NTSB had also recommended to implement information filtering in the crew alert systems.[65] "For example, the erroneous AOA output experienced during the two accident flights resulted in multiple alerts and indications to the flight crews, yet the crews lacked tools to identify the most effective response. Thus, it is important that system interactions and the flight deck interface be designed to help direct pilots to the highest priority action(s)."

On October 2, 2019, The Seattle Times and The New York Times reported that a Boeing engineer, Curtis Ewbank, filed an internal ethics complaint alleging that company managers rejected a backup system for determining speed, which might have alerted pilots to problems linked to two deadly crashes of 737 MAX.[66] A similar backup system is installed on the larger Boeing 787 jet, but it was rejected for the 737 MAX because it could increase costs and training requirements for pilots. Ewbank said the backup system could have reduced risks that contributed to two fatal crashes, though he could not be sure that it would have prevented them. A backup speed system "could also detect when sensors measuring the direction of the plane's nose weren't working". He also said in his complaint that Boeing management was more concerned with costs and keeping the MAX on schedule than on safety.[67][68] An attorney representing families of the Ethiopian crash victims will seek sworn evidence from the whistleblower.[69]

As of May 2020, the FAA and EASA have reversed some, if not all, of these design decisions, requiring Boeing to design and retrofit critical systems on all aircraft once the airplane returns to service.[70]

Boeing 737 safety analysis

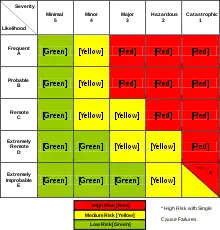

Recognized civil aviation development practices, such as those of SAE International ARP4754 and ARP4761, require a safety process with quantitative assessments of availability, reliability, and integrity, validation of requirements, and verification of implementation. Such processes rely on engineering judgment and the application of these practices varies within the industry.[71][72] Redundancy is a technique that may be used to achieve the quantitative safety requirements.[73]

Aviation safety risk is defined in AC 25.1309-1, an FAA document describing acceptable means for showing compliance with the airworthiness requirements of § 25.1309 of the Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR). A catastrophic failure must have an extremely improbable rate, defined as one in a billion flight hours, also stated as less than 10−9 per flight hour.[74]

By this measure, as of 2005, the Boeing 737 had an actual fatal accident rate of 1 in 80 million flight hours, missing the requirements by an order of magnitude.[75]

In the two years of the 737 MAX's commercial service prior to its grounding, the global fleet of nearly 400 aircraft flew 500,000 flights and suffered two hull loss incidents. As of March 11, 2019, the 737 MAX's accident rate was second behind the Concorde, with four accidents per million flights, compared to the 737NG 0.2 accidents per million flights.[76]

MCAS and MAX safety risk analysis

The Lion Air accident report provides insight on the classification of failure conditions related to MCAS, and resulting safety assessment and testing:[77]

Because uncommanded MCAS function was considered "Major," Boeing did not perform a specific fault tree analysis for an uncommanded MCAS hazard. One of these hazards, applicable to the MCAS function seen in this accident, included uncommanded MCAS operation to original maximum authority of 0.6°. Boeing indicated that, as part of the functional hazard assessment development, flight crew assessments of MCAS-related hazards were conducted in an engineering flight simulator with motion capability, including the uncommanded MCAS operation (stabilizer runaway) to the MCAS maximum authority.

This assessment of Major failure effect did not require Boeing to more rigorously analyze the failure condition in the safety analysis, using Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) and Fault Tree Analysis (FTA), as these are only required for Hazardous or Catastrophic failure conditions.

During the process of developing and validating the Functional Hazard Analysis (FHA), Boeing considered four failure scenarios including uncommanded MCAS function to the maximum authority limit of 2.5° of stabilizer movement. The uncommanded MCAS function to maximum authority was only flight simulated to high speed maximum limit of 0.6°, however, not to low speed maximum limit of 2.5° of stabilizer movement. Boeing also not considered repetitive erroneous MCAS activations.

In response to the Lion Air crash, the FAA conducted an internal study of the safety of the 737 MAX. The study, not made public, used the Transport Airplane Risk Assessment Methodology (TARAM) and was completed on December 3, 2018, slightly more than a month after the accident. Just over a year later, on December 11, 2019, the US House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure released the study and described its conclusion by stating, "if left uncorrected, the MCAS design flaw in the 737 Max could result in as many as 15 future fatal crashes over the life of the fleet".[78]

Boeing stated that, based on the TARAM analysis:

"...an FAA Corrective Action Review Board—the FAA's established process for evaluating safety issues—determined that Boeing's and the FAA's actions in early November [2018] to reinforce existing pilot procedures through issuance of an Operations Manual Bulletin and Airworthiness Directive sufficed to allow continued operation of the MAX fleet until changes to the MCAS software could be implemented. Boeing's own TARAM analysis was consistent with the FAA's conclusions."[79]

The FAA report was refuted by MIT professor Arnold Barnett based on the loss of two aircraft out of only 400 delivered. He said there would be 24 crashes per year for a fleet size of 4,800, thus the FAA underestimated the risk by a factor of 72.[80]

On March 6, 2019, four days prior to the Ethiopian crash, Boeing and the FAA declined to comment regarding their safety analysis of MCAS for a story in The Seattle Times. On March 17, a week after the crash, The Seattle Times published the following flaws as identified by aviation engineers:[22]

- Boeing's service bulletin informed airlines that the MCAS could deflect the tail in increments up to 2.5°, more than the 0.6° told to the FAA in the safety assessment;[22]

- MCAS could reset itself after each pilot response to repeatedly pitch the aircraft down;[22]

- The capability of MCAS had been downplayed, and its failure assessment was rated as "hazardous", one level below "catastrophic"[22]

- MCAS relied on a single angle of attack sensor.[22]

In its safety analysis for the 737 MAX, Boeing made the assumption that pilots trained on standard Boeing 737 safety procedures should be able to properly assess contradictory warnings and act effectively within four seconds.[81] This four-second rule, for a pilot's assessment of an emergency and its correction, a standard value used in safety assessment scenarios for the MAX, is deemed too short, and criticized for not being supported by empirical human factors studies.[82] The Lion Air accident investigation report found that on the fatal flight and on the previous one, crews responded in about 8 seconds. According to the report, Boeing reasoned that pilots could counter an erratic MCAS by pulling back on the control column alone, without using the cutout switches. MCAS could only be stopped by the cutoff switches, however.[83]

Documentation made public at the House hearing on October 30, 2019, "established that Boeing was also already well aware, before the Lion Air accident, that if a pilot did not react to unintended MCAS activation within 10 seconds, the result could be catastrophic."[84]

Effect on air transport safety

In December 2019, the German aviation audit company Jet Airliner Crash Data Evaluation Center (JACDEC), which is based in Hamburg, reported using the "Safety Risk Index" method that casualties in air crashes in 2019 nearly halved over 2018: 293 fatalities in 2019 compared to 559 in the previous year.[85] On January 1, 2020, the Dutch aviation consultancy, To70, published its annual "Civil Aviation Safety Review", which recorded that in 2019 there were 86 accidents, 8 of which were fatal, resulting in 257 fatalities.[86] Both results showed that the death toll of 157 in the MAX crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 made more than the half of the fatalities.

Jan-Arwed Richter, head of JACDEC said: "The sharp reduction in fatalities compared to 2018 is—at the risk of sounding macabre—due to the grounding of the 737 MAX in March."[85] Whilst Adrian Young, the author of To70's report, said: "Despite a number of high profile accidents this year's fatal accident rate is lower than the average of the last five years."[86]

US Department of Justice inquiries

A U.S. federal grand jury issued a subpoena on behalf of the Department of Justice (DOJ) for documents related to development of the 737 MAX.[87][88][89][90]

On January 7, 2021, Boeing settled to pay over $2.5 billion after being charged with fraud: a criminal monetary penalty of $243.6 million, $1.77 billion of damages to airline customers, and a $500 million crash-victim beneficiaries fund.[91][92]

US Congress inquiries

In March 2019, Congress announced an investigation into the FAA approval process.[93] Members of Congress and government investigators expressed concern about FAA rules that allowed Boeing to extensively "self-certify" aircraft.[94][95] FAA acting Administrator Daniel Elwell said "We do not allow self-certification of any kind".[96] Initially, as a new system or a new device on the amended type certificate, the FAA retained the oversight of MCAS. The FAA later released it to the Boeing Organization Designation Authorization (ODA) based on comfort level and thorough examination, Elwell said in March. "We were able to assure that the ODA members at Boeing had the expertise and the knowledge of the system to continue going forward."[96] Several FAA insiders believed the delegation went too far.[97][22] Boeing pilot Mark A Forkner was subsequently indicted on charges of supplying false and incomplete information to the FAA in respect of the certification of the 737 MAX.[98]

Senate

On April 2, 2019, after receiving reports from whistle-blowers regarding the training of FAA inspectors who reviewed the 737 MAX type certificate, the Senate Commerce Committee launched a second Congressional investigation; it focuses on FAA training of the inspectors.[99][100] The FAA provided misleading statements to Congress about the training of its inspectors, most possibly those inspectors that oversaw the MAX certification, according to the findings of an Office of Special Counsel investigation released in September.

In February 2020, three Senate Transportation Committee members introduced a "Restoring Aviation Accountability" bill, which would specifically require implementation of the Joint Authorities Technical Review's recommendations, and more generally would set up a commission to review the FAA safety delegation process and assess alternative certification schemes that could provide more robust oversight.[101]

In December 2020, a report by the Senate committee on commerce, science and transportation found that Boeing "inappropriately coached" pilots while conducting simulator tests during the recertification process, by reminding them of the correct response to a runaway stabilizer, and accused Boeing and the FAA of establishing a "pre-determined outcome to reaffirm a long-held human factor assumption" regarding pilot reaction times.[102] The simulated flight by FAA pilots took place in July 2019, predating a major redesign of MCAS.[103]

It appears, in this instance, FAA and Boeing were attempting to cover up important information that may have contributed to the 737 MAX tragedies.[104]

House of Representatives

On June 7, the delayed escalation on the defective AoA Disagree alert on 737 MAX was investigated. The Chair of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and the Chair of the Aviation Subcommittee sent letters to Boeing, United Technologies Corp., and the FAA, requesting a timeline and supporting documents related to awareness of the defect, and when airlines were notified.[105]

In September 2019, a Congress panel asked Boeing's CEO to make several employees available for interviews, to complement the documents and the senior management perspective already provided.[106] The same month, Boeing's board called for changes to improve safety.[107] Representative Peter DeFazio, chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, said Boeing declined his invitation to testify at a House hearing. "Next time, it won't just be an invitation, if necessary," he said. Later, in the same month, the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee announced that Boeing CEO, Dennis Muilenburg, will testify before Congress accompanied by John Hamilton, chief engineer of Boeing's Commercial Airplanes division and Jennifer Henderson, 737 chief pilot.[108] In October 2019, the House asked Boeing to allow a flight deck systems engineer who filed an internal ethics complaint to be interviewed.[68]

On October 18, Peter DeFazio said "The outrageous instant message chain between two Boeing employees suggests Boeing withheld damning information from the FAA". Boeing expressed regret over its ex-pilot's messages after their publication in media.[109] Boeing's media room released a statement about Forkner's meaning of the instant messages, obtained through his attorney because the company has not been able to talk to him directly. The transcript of the messages indicates, according to experts, a problem with the simulator rather than an MCAS erratic activation.[110][111][32]

On October 25, 2019, Peter DeFazio commented the Lion Air accident report, saying "And I will be introducing legislation at the appropriate time to ensure that unairworthy commercial airliners no longer slip through our regulatory system".[112]

The aviation subcommittee and full committee hearings follow:

The Subcommittee on Aviation met on June 19, 2019, to hold a hearing titled "Status of the Boeing 737 MAX: Stakeholder Perspectives".

"The hearing is intended to gather views and perspectives from aviation stakeholders regarding the Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 accidents, the resulting international grounding of the Boeing 737 MAX aircraft, and actions needed to ensure the safety of the aircraft before returning them to service. The Subcommittee will hear testimony from Airlines for America, Allied Pilots Association, Association of Flight Attendants—CWA, Captain Chesley (Sully) Sullenberger, and Randy Babbitt."[113][114]

On July 17, representatives of crash victims' families, in testimony to the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee – Aviation Subcommittee, called on regulators to re-certificate the MAX as a completely new aircraft. They also called for wider reforms to the certification process, and asked the committee to grant protective subpoenas so that whistle-blowers could testify even if they had agreed to a gag order as a condition of a settlement with Boeing.[115] In a July 31 senate hearing, the FAA defended its administrative actions following the Lion Air accident, noting that standard protocol in ongoing crash investigations limited the information that could be provided in the airworthiness directive.[116][117]

On October 29, 2019, Muilenburg and Hamilton appeared at the House hearing under the title "Aviation Safety and the Future of Boeing's 737 MAX", which was the first time that Boeing executives addressed Congress about the MAX accidents.[118][119] The hearing came on the heels of the removal of Dennis Muilenburg's title as chairman of the Boeing board a week before and was intended to examine issues associated with the design, development, certification, and operation of the Boeing 737 MAX following two accidents in the last year.[119] The committee first heard from Boeing on actions taken to improve safety and the company's interaction with relevant federal regulators. The second panel was composed of government officials and aviation experts discussing the status of Boeing 737 MAX and relevant safety recommendations."[118]

On October 30, the House made public a 2015 internal email discussion between Boeing employees raising concerns about MCAS design in the exact scenario blamed for the two crashes: "Are we vulnerable to single AOA sensor failures with the MCAS implementation?"[120] Committee members discussed another internal document, stating that a reaction longer than 10 seconds to an MCAS malfunction "found the failure to be catastrophic."[120][121] The hearings' key revelation was insider knowledge of vulnerabilities amid a hectic rate of production.[122]

After the testimony of Boeing's CEO, Peter DeFazio and Rick Larsen, leader of its aviation sub-panel, wrote a letter to other lawmakers on November 4, saying that unanswered questions remain: "Mr. Muilenburg left a lot of unanswered questions, and our investigation has a long way to go to get the answers everyone deserves [...] Mr. Muilenburg's answers to our questions were consistent with a culture of concealment and opaqueness and reflected the immense pressure exerted on Boeing employees during the development and production of the 737 Max".[123]

On December 11, 2019, during a hearing of the House Committee on Transportation titled "The Boeing 737 MAX: Examining the Federal Aviation Administration's Oversight of the Aircraft's Certification," an internal FAA review[124] dated December 3, 2018, was released, which predicted a high MAX accident rate, if it kept flying with MCAS unchanged.[125] The findings were first reported by The Wall Street Journal in July 2019,[126] The FAA assumed that the emergency airworthiness directive sufficed until Boeing delivered a fix.[127] Over a question whether a mistake was made in this regard, the FAA's chief Stephen Dickson responded, "Obviously the result was not satisfactory."[128][129] Peter DeFazio said that the committee's investigation "has uncovered a broken safety culture within Boeing and an FAA that was unknowing, unable, or unwilling to step up, regulate and provide appropriate oversight of Boeing".[130]

"But perhaps most chillingly, we have learned that shortly after the issuance of the airworthiness directive, the FAA performed an analysis that concluded that, if left uncorrected, the MCAS design flaw in the 737 MAX could result in as many as 15 future fatal crashes over the life of the fleet—and that was assuming that 99 out of 100 flight crews could comply with the airworthiness directive and successfully react to the cacophony of alarms and alerts recounted in the National Transportation Safety Board's report on the Lion Air tragedy within 10 seconds. Such an assumption, we know now, was tragically wrong."

"Despite its own calculations, the FAA rolled the dice on the safety of the traveling public and let the 737 MAX continue to fly until Boeing could overhaul its MCAS software. Tragically, the FAA's analysis—which never saw the light of day beyond the closed doors of the FAA and Boeing—was correct. The next crash would occur just five months later, when Ethiopian Airlines flight 302 plummeted to earth in March 2019."[131]

In January 2020, Kansas Rep. Sharice Davids, member of the House Transportation Committee and is vice chair of its aviation subcommittee, said: "The newly released messages from Boeing employees are incredibly disturbing and show a coordinated effort inside the company to deceive the American public and federal regulators, who are in place to keep passengers safe. It's further proof that Boeing put profit over safety in the development of the 737 MAX. [...] In addition to the public safety concerns these messages raise, Boeing's callousness has now cost thousands of Kansans their livelihood and endangered the economy of our state, which is dependent on aerospace."[132][133]

On March 6, 2020, the House Transportation Committee said that a "culture of concealment" at the company and poor oversight by federal regulators contributed to the crashes. In a preliminary summary of its nearly yearlong investigation, the committee said multiple factors had led to the crashes, but focused on the MCAS, which Boeing had failed to classify as safety critical, part of a strategy designed to avoid closer scrutiny by regulators as the company developed the plane. The panel said that Boeing had undue influence over the Federal Aviation Administration, and that FAA managers rejected safety concerns raised by their own technical experts.[134][135] The preliminary report was prepared by the Democratic Staff of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure.[136]

In September 2020, concluding an 18-month investigation, a House report produced by Democratic staff of the Committee blamed Boeing and the FAA for lapses in the design, construction and certification of the MAX: Boeing made production and cost goals a higher priority than safety; Boeing made deadly assumptions about MCAS, causing the planes to nosedive; Boeing withheld critical information from the FAA; Delegation of oversight authority to Boeing employees left the FAA unaware of important issues; FAA management sided with Boeing against its own experts.[137][6][138]

US Office of Special Counsel inquiries

The Office of Special Counsel is an organization investigating whistleblower reports. Its report infers that safety inspectors "assigned to the 737 Max had not met qualification standards".[139] The OSC sided with the whistleblower, pointing out that internal FAA reviews had reached the same conclusion. In a letter to President Trump, the OSC found that 16 of 22 FAA pilots conducting safety reviews, some of them assigned to the MAX two years ago, "lacked proper training and accreditation."[140]

Safety inspectors participate in Flight Standardization Boards, that ensure pilot competency by developing training and experience requirements. FAA policy requires both formal classroom training and on-the-job training for safety inspectors.[141]

Special Counsel Henry J. Kerner wrote in the letter to the President, "This information specifically concerns the 737 Max and casts serious doubt on the FAA's public statements regarding the competency of agency inspectors who approved pilot qualifications for this aircraft".[142]

In September, Daniel Elwell disputed the conclusions of the OSC, which found that aviation safety inspectors (ASIs) assigned to the 737 MAX certifications did not meet training requirements.[143][144] To clarify the facts, lawmakers asked the FAA to provide additional information:

"We are particularly concerned about the Special Counsel's findings that inconsistencies in training requirements have resulted in the FAA relaxing safety inspector training requirements and thereby adopting "a position that encourages less qualified, accredited, and trained safety inspectors." We request that the FAA provide documents confirming that all FAA employees serving on the FSB for the Boeing 737-MAX and the Gulfstream VII had the required foundational training in addition to any other specific training requirements."[145]

US Cabinet inquiries

The FBI has joined the criminal investigation into the certification as well.[148][149] FBI agents reportedly visited the homes of Boeing employees in "knock-and-talks".[150]

At the request of Peter DeFazio, and Chair of the Subcommittee on Aviation Rick Larsen, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Inspector General opened an investigation into FAA approval of the Boeing 737 MAX aircraft series, focusing on potential failures in the safety-review and certification process.[151]

A report released on October 23 says that the FAA faces a "significant oversight challenge" to ensure that manufacturers carrying out delegated certification activities "maintain high standards and comply with FAA safety regulations", and that it plans to introduce a "new process that represents a significant change in its approach" by March 2020.[152][153] In April 2019, U.S. Secretary of Transportation, Elaine L. Chao, who boarded a MAX flight on March 12 amid calls to ground the aircraft,[154] created the Special Committee to Review the FAA's Aircraft Certification Process to review of Organization Designation Authorization, which granted Boeing authority to review systems on behalf of the FAA, during the certification of the 737 MAX 8. The committee recommended integrating human performance factors and consider all levels of pilot experience, but defended the ODA against any reforms.[155][156] Relatives of those on board the accident flights condemned the report for calling the ODA an "effective" process.[157]

U.S. NTSB

On September 26, 2019, the NTSB released the results of its review of potential lapses in the design and approval of the 737 MAX.[158][159]: 1 [160] The report concludes that Boeing's assumptions about pilot reaction to MCAS activation "did not adequately consider and account for the impact that multiple flight deck alerts and indications could have on pilots' responses to the hazard". Before the airplane began service, Boeing had evaluated pilot response to simulated MCAS activation, but the NTSB noted that Boeing did not simulate a specific cause, such as erroneous AoA input, or the multiple cockpit alerts and warnings that could result. The NTSB said those "alerts and indications can increase pilots' workload, and the combination of the alerts and indications did not trigger the accident pilots to immediately perform the runaway stabilizer procedure". It stated, "the pilot responses differed and did not match the assumptions of pilot responses to unintended MCAS operation on which Boeing based its hazard classifications".[159][161]

The NTSB questioned the long-held industry and FAA practice of assuming the nearly instantaneous responses of highly trained test pilots, as opposed to pilots of all levels of experience to verify human factors in aircraft safety.[162] The NTSB expressed concerns that the process used to evaluate the original design needs improvement because that process is still in use to certify current and future aircraft and system designs. The FAA could for example randomly sample pools from the worldwide pilot community to get a more representative assessment of cockpit situations.[163]

Return to service

Boeing

In early October 2019, CEO Muilenburg said that Boeing's own test pilots had completed more than 700 flights with the MAX.[164] Certification flight tests, because of the ongoing safety review, were thought unlikely to occur before November.[165] Boeing made "dry runs" of the certification test flights on October 17, 2019.[166] As of October 28, Boeing had conducted "over 800 test and production flights with the updated MCAS software, totaling more than 1,500 hours".[167]

As of October 8, Boeing was fixing a flaw discovered in the redundant-computer architecture of the 737 MAX flight-control system.[168] The FAA and the EASA were still reviewing changes to the MAX software, raising questions about the return to service forecast. The FAA was to review Boeing's "final system description", which specifies the architecture of the flight control system and the changes that Boeing have made, and perform an "integrated system safety analysis"; the updated avionics were to be assessed for pilot workload.[165] The FAA was specifically looking at six "non-normal" checklists that could be resequenced or changed. The assessment of these checklists with pilots could happen at the end of October, according to an optimistic forecast.[169]

As of mid-November 2019, Boeing still needed to complete an audit of its software documentation. A key certification test flight was to follow the audit. In a memo and a video dated November 14, FAA's Steve Dickson instructed his staff to "take whatever time is needed" in their review, repeating that approval is "not guided by a calendar or schedule."[170][171]

At the request of the FAA, Boeing audited key systems on the MAX. In January 2020, Boeing discovered that electrical wiring bundles were too close together and could cause a short circuit that could theoretically lead to a runaway stabilizer.[172] The EASA wants the wiring fixed on all 400 grounded aircraft and future deliveries. Boeing and the FAA disagreed with EASA at first,[173] but the FAA said to Boeing in March 2020 that the wiring is not compliant.[174]

A manufacturing fault was also found to have affected the lightning protection foil on two panels covering the engine pylons on certain MAX aircraft manufactured between February 2018 and June 2019.[175] On February 26, 2020, the FAA has proposed a corresponding airworthiness directive to mandate repairs to all affected aircraft.[176]

In January 2020, the FAA proposed a $5.4 million fine against Boeing for installing nonconforming slat tracks. The tracks are used to guide the movement of slats, which are panels located on the leading edge of aircraft's wings for additional lift during take-off and landing. Boeing's supplier did not comply with aviation regulations nor with Boeing's quality assurance system. Boeing is alleged to have issued airworthiness certificates for 178 MAX aircraft despite knowing that the slat tracks had failed a strength test.[177]

In February 2020, traces of debris were discovered within the fuel tanks of aircraft produced during the groundings.[178] FAA set out the remaining steps in the process to ungrounding the aircraft: after remaining minor issues are resolved, a certification flight will be conducted and flight data will be assessed. Operational validation, including assessment of Boeing's training proposals by international and U.S. crews, as well as by the FAA administrator and his deputy in person, will then proceed, followed by documentation steps. U.S. airlines will then need to obtain FAA approval for their training programs. Each aircraft will be issued with an airworthiness certificate and will be required to conduct a validation flight without passengers.[179] The FAA said it would require airlines perform "enhanced inspections and fixes to portions of an outside panel that helps protect the engines on Boeing's 737 Max from lightning strikes".[180] Boeing conducted numerous test flights in 2020, before a series of FAA recertification flights from June 28 to July 1, 2020. These were performed by a 737 MAX 7, flying from Boeing Field, Seattle, to Boeing's test facilities at Moses Lake and back.[181][182]

FAA

The FAA certifies the design of aircraft and components that are used in civil aviation operations. The FAA is "performance-based, proactive, centered on managing risk, and focused on continuous improvement."[183] As with any other FAA certification, the MAX certification included: reviews to show that system designs and the MAX complied with FAA regulations; ground tests and flight tests; evaluation of the airplane's required maintenance and operational suitability; collaboration with other civil aviation authorities on aircraft approval.

Due to the global scrutiny following the two fatal accidents, the FAA is re-evaluating its certification process and seeking consensus with other regulators to approve the return to service to avoid suspicion of undue cooperation with Boeing.[184] The International Air Transport Association (IATA) had also made a similar statement calling for more coordination and consensus with training and return to service requirements.[185] In March 2019, reports emerged that Boeing performed the original System Safety Analysis, and FAA technical staff felt that managers pressured them to sign off on it. Boeing managers also pressured engineers to limit safety testing during the analysis.[186] A 2016 Boeing survey found almost 40% of 523 employees working in safety certification felt "potential undue pressure" from managers.[109][187] Since June 2019, the FAA has reiterated many times that it does not have a timetable on when the 737 MAX will return to service,[188] stating that it is guided by a "thorough process, not a prescribed timeline."[189] The FAA identified new risks of failure during thorough testing. As a result, Boeing worked to make the overall flight-control computer more redundant, such that both computers will operate on each flight instead of alternating between flights. The planes were said to be unlikely to resume operations until 2020.[190][191][186]

- In August 2019, reports emerged of friction between Boeing and certain international air-safety authorities. A Boeing briefing was stopped short by the FAA, EASA, and other regulators, on the grounds that Boeing had "failed to provide technical details and answer specific questions about modifications in the operation of MAX flight-control computers."[192][193] A U.S. official confirmed frustration with some of Boeing's answers.[106]

- On October 2, 2019, The Seattle Times reported that Boeing convinced FAA regulators to relax certification requirements in 2014, that would have added over $10 billion in 2013 dollars to the development cost to the MAX.[2]

- In October 2019, according to current and former FAA officials, instead of increasing its oversight powers, the FAA "has been pressing ahead with plans to further reduce its hands-on oversight of aviation safety".[29]

- On October 22, 2019, FAA Administrator Steve Dickson said in a news conference that the agency had received the "final software load" and "complete system description" of revisions; several weeks of work are anticipated for certification activities.[194] Final simulator-based assessments were expected to start in November 2019.[195]

- In October 2019, the FAA requested that Boeing turn over internal documents and explain why it did not disclose the Forkner messages earlier.[196] The FAA is aware of "more potentially damaging messages from Boeing employees that the company has not turned over to the agency".[197]

- In November 2019, the FAA announced that it had withdrawn Boeing's authority, previously held under the Organization Designation Authorization, to issue airworthiness certificates for individual new 737 MAX aircraft. The FAA denied allegations that the ODA enabled plane makers to police themselves or self-certify their aircraft.[198][199] After the overall grounding is lifted, the FAA will issue such certificates directly; aircraft already delivered to customers will not be affected.[200] In the same month, the FAA pushed back at Boeing's attempts to publicize a certification date, saying the agency will take all the time it needs.[201]

- On December 9, 2019, in an internal email sent to employees in the FAA's Aircraft Certification Service (AIR), it was revealed that the agency was moving to create a new safety branch to address shortcomings in its oversight following the two MAX crashes and a controversial reorganization. The email obtained by The Washington Post emphasized the complexities of aviation safety, but did not mention the MAX directly as it was written in bureaucratic language.[202]

- December 2019, The Air Current reported on pilots attempting the procedure with "inconsistent, confusing" results.[203]

- On December 6, 2019, the FAA posted an updated Master minimum equipment list for the 737 MAX; in particular, both flight computers must be operational before flight, as they now compare each other's sensors prior to activating MCAS.[204]

- On December 11, 2019, Dickson announced that MAX would not be recertified before 2020, and reiterated that FAA did not have a timeline.[205][206] The following day, Dickson met with Boeing chief executive Dennis Muilenburg to discuss Boeing's unrealistic timeline and the FAA's concerns that Boeing's public statements may be perceived as attempting to force the FAA into quicker action.[207]

- In January 2020, Boeing targeted mid-2020 for recertification, but the FAA expressed that it was "pleased" with progress made and may approve the aircraft sooner within the United States.[208]

- In February 2020, the FAA explained why the agency waited for empirical evidence to draw a common link to the crashes before grounding the airplane.[209]

- In April 2020, the second revision to the list removed several exemptions and fault tolerances to ensure greater availability of the aircraft's redundant systems.[210]

- On September 30, 2020, FAA administrator and former Delta Air Lines Boeing 737 captain, Stephen Dickson, conducted a two-hour test flight at the controls of the MAX, after completing the new training proposed by Boeing.[211] He had previously announced that the FAA would not certify the MAX until he had flown the aircraft himself.[212][213]

- On November 18, 2020, the FAA issued a Continuing Airworthiness Notification that rescinded its grounding order, subject to mandatory updates on each individual aircraft.[lower-alpha 1][214] Other regulators are independent and are expected to follow; some are waiting for the EASA.[215]

Public commentaries

On August 3, 2020, the FAA announced its final list of design, operation, maintenance and training changes that must be completed before the MAX can return to service. The design changes include updated flight software, a new angle of attack sensor failure alert, revised crew manuals and changes to wiring routing. All design approvals were conducted by the FAA directly; no oversight was delegated to Boeing.[216] The design changes must be implemented on all MAX aircraft already produced and in storage, as well as new production.[217] The FAA documents were published in the Federal Register on August 6, opening a 45-day public comment period.[218] The FAA's response and final Airworthiness Directive is then expected to be published no earlier than mid-October, with U.S. domestic flights expected to resume 30 to 60 days later.[219]

During the FAA public comment period, EASA inquired about adding a third angle of attack sensor, and Transport Canada inquired whether the stick shaker, a mechanical stall warning device, could be suppressed during false alarm situations to reduce pilot workload.[220] Airline passenger organization FlyersRights remain skeptical whether the proposed software and computer fixes sufficiently mitigate inherent flaws with the MAX's airframe.[221] The British Airline Pilots' Association warned that one of the proposed changes to recovery procedures, which may require effort from both pilots to operate the manual trim wheel, is "extremely undesirable" and could result in a scenario similar to the Ethiopian Airlines crash.[222] The National Safety Committee of the National Air Traffic Controllers Association recommended that the MAX should be required to meet all current requirements relating to crew alerting systems (whereas it currently benefits from exemptions).[223]

Technical Advisory Board

The Technical Advisory Board, a multi-agency panel, was created shortly after the second crash, as a panel of government flight-safety experts for independently reviewing Boeing's redesign of the MAX. It includes experts from the United States Air Force (USAF), the Volpe National Transportation Systems Center, NASA and FAA. "The TAB is charged with evaluating Boeing and FAA efforts related to Boeing's software update and its integration into the 737 Max flight control system. The TAB will identify issues where further investigation is required prior to FAA approval of the design change", said the FAA.[224] The TAB reviewed Boeing's MCAS software update and system safety assessment.[225] On November 8, the TAB presented its preliminary report to the FAA, finding that the MCAS design changes are compliant with the regulations and safe.[226]

Joint Authorities Technical Review

On April 19, 2019, a multinational "Boeing 737 MAX Flight Control System Joint Authorities Technical Review" (JATR) team was commissioned by the FAA to investigate how it approved MCAS, whether changes need to be made in the FAA's regulatory process and whether the design of MCAS complies with regulations.[228] On June 1, Ali Bahrami, FAA Associate Administrator for Aviation Safety, chartered the JATR to include representatives from FAA, NASA and the nine civil aviation authorities of Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Europe (EASA), Indonesia, Japan, Singapore and UAE.

On September 27, the JATR chair Christopher A. Hart said that FAA's process for certifying new airplanes is not broken, but needs improvements rather than a complete overhaul of the entire system. He added "This will be the safest airplane out there by the time it has to go through all the hoops and hurdles".[229]

The JATR said that FAA's "limited involvement" and "inadequate awareness" of the automated MCAS safety system "resulted in an inability of the FAA to provide an independent assessment".[230] The panel report added that Boeing staff performing the certification were also subject to "undue pressures... [that] further erode[] the level of assurance in this system of delegation".[231]

About the nature of MCAS, "the JATR team considers that the STS/MCAS and EFS functions could be considered as stall identification systems or stall protection systems, depending on the natural (unaugmented) stall characteristics of the aircraft".[232]

The report recommends that FAA reviews the jet's stalling characteristics without MCAS and associated system to determine the plane's safety and consequently if a broader design review was needed.[233]

"Boeing elected to meet the objectives of SAE International's Aerospace Recommended Practice 4754A, Guidelines for Development of Civil Aircraft and Systems (ARP4754A) for development assurance of the B737 MAX. [...] The use of ARP4754A is consistent with the guidance contained in FAA Advisory Circular (AC) 20-174, Development of Civil Aircraft and Systems. The JATR team identified areas where the Boeing processes can be improved to more robustly meet the development assurance objectives of ARP4754A.[...]

An integrated SSA to investigate the MCAS as a complete function was not performed. The safety analyses were fragmented among several documents, and parts of the SSA from the B737 NG were reused in the B737 MAX without sufficient evaluation.[...]

The JATR team identified specific areas related to the evolution of the design of the MCAS where the certification deliverables were not updated during the certification program to reflect the changes to this function within the flight control system. In addition, the design assumptions were not adequately reviewed, updated, or validated; possible flight deck effects were not evaluated; the SSA and functional hazard assessment (FHA) were not consistently updated; and potential crew workload effects resulting from MCAS design changes were not identified."[232]

The JATR found that Boeing did not carry out a thorough verification by stress-testing of the MCAS.[234] The JATR also found that Boeing exerted "undue pressures" on Boeing ODA engineering unit members (who had FAA authority to approve design changes).[232][235]

FAA Airworthiness Directive for return to service

To address the unsafe conditions that led to the grounding of the Boeing 737 MAX, the FAA issued an Airworthiness Directive that requires four design changes:

- Installing new flight control computer software. This change is intended to prevent erroneous MCAS activation, among other safeguards.

- Installing updated cockpit display system software to generate an AOA disagree alert. This will alert the pilots that the airplane's two AOA sensors are disagreeing by a certain amount indicating a potential AOA sensor failure.

- Incorporating new and revised operating procedures into the Airplane Flight Manual. This change is intended to ensure the flight crew has the means to recognize and respond to erroneous stabilizer movement and the effects of a potential AOA sensor failure.

- Changing the routing of horizontal stabilizer trim wires. This is intended to bring the airplane into full compliance with the FAA's wire-separation safety standards.

In addition to these four design changes, the FAA also will require operators to conduct an AOA sensor system test and perform an operational readiness flight prior to returning each airplane to service.

The FAA also indicated that non-U.S.-registered MAX aircraft would not be allowed access to U.S. airspace if the aviation authority of the state of registration does not require compliance with the amended design or "an alternative that achieves at least an equivalent level of safety", pursuant to Article 33 of the ICAO Chicago Convention.[237] It has also been suggested that, under Article 33, other countries have no legal grounds to continue banning U.S.-registered MAX aircraft from their airspace even if they have not themselves authorized the resumption of flights. As of January 26, 2021, this remains a purely theoretical issue.[238]

FAA CANIC for return to service

The FAA issued a CANIC to notify the international community of the final rule/airworthiness directive (AD) for return to service and that it rescinded the Emergency Order of Prohibition. It also notifies of the release of documents: Summary of the FAA's Review of the Boeing 737 MAX; Boeing 737 Flight Standardization Board Report, identifying special pilot training for the 737 MAX; FAA Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO) identifying changes to pilot training; and FAA SAFO identifying changes to the maintenance program.[239]

EASA

The EASA and Transport Canada announced they will independently verify FAA recertification of the 737 MAX.[240][241]

For product certifications, the EASA is already in the process of significantly changing its approach to the definition of Level of Involvement (LoI) with Design Organisations. Based on an assessment of risk, an applicant makes a proposal for the Agency's involvement "in the verification of the compliance demonstration activities and data". EASA considers the applicant's proposal in determining its LOI.[242][243][244]

In a letter sent to the FAA on April 1, 2019, EASA stated four conditions for recertification: "1. Design changes proposed by Boeing are EASA approved (no delegation to FAA) 2. Additional and broader independent design review has been satisfactorily completed by EASA 3. Accidents of JT610 and ET302 are deemed sufficiently understood 4. B737 MAX flight crews have been adequately trained."[245]

In a May 22 statement, the EASA reaffirmed the need to independently certify the 737 MAX software and pilot training.[246] In addition to system analysis mentioned above, EASA raised concerns with the autopilot not engaging or disengaging upon request, or that the manual trim wheel is electronically counteracted upon, or requires substantial physical force to overcome the aerodynamic effects in flight.[247]

In September 2019, the European Union received parliamentary questions for written answers about the independent testing and re-certification of critical parts of the Boeing 737 MAX by the EASA:[248]

- Could the Commission confirm whether these tests will extend beyond the MCAS flight software issue to the real problem of the aerodynamic instability flaw that the MCAS software was created to address?

- Does the Commission have concerns about the limited scope of the FAA's investigation into the fatal loss of control, and is EASA basing its re-certification of the 737 Max on that investigation?

- What assurances can the Commission give that the de facto delegation of critical elements of aircraft certification to the same company that designed and built the aircraft, and the practice of delegated oversight, does not exist in Europe?

EASA stated it was satisfied with changes to the flight control computer architecture; improved crew procedures and training are considered a simplification but still work in progress; the integrity of the angle of attack system is still not appropriately covered by Boeing's response. The EASA recommends a flight test to evaluate aircraft performance with and without the MCAS.[249][245][250] EASA said it will send its own test pilots and engineers to fly certification flight tests of the modified 737 MAX. EASA also said it prefers a design that takes readings from three independent Angle of Attack sensors.[251] EASA's leaders want Boeing and the FAA to commit for longer-term safety enhancements. Mr. Ky is said to seek a third source of the angle of attack. EASA is contemplating the installation of a third sensor or equivalent system at a later stage, once the planes return to service.[164]

On October 18, 2019, EASA Executive Director Patrick Ky said: "For me it is going to be the beginning of next year, if everything goes well. As far as we know today, we have planned for our flight tests to take place in mid-December which means decisions on a return to service for January, on our side".[252]

On August 27, 2020, EASA announced that it planned to start flight testing the MAX on September 7. The flight tests, conducted in Vancouver, Canada, would follow a week of simulator work at London Gatwick Airport. Afterward, the Joint Operations Evaluation Board (JOEB) would start its testing procedures on September 14.[253]

On November 18, 2020, after the FAA cleared the MAX for return to service in the U.S., EASA indicated that it would shortly issue its own proposed airworthiness directive. After the 28-day public comment period, the final directive would then be published in late December 2020 or early in 2021.[254]

On January 27, 2021, EASA formally cleared the MAX to resume service.[9] The main difference with FAA requirements is the ability (also mandated by Transport Canada) to disable the stick-shaker warning if pilots are certain that they understand the underlying cause.[255] Certain approaches requiring precision navigation are not yet approved as EASA is awaiting data from Boeing as to the aircraft's ability to maintain the required performance in the event of sensor failures.[256]

Some EASA member states issued their own orders banning the MAX from their airspace; these individual bans will also need to be lifted.[257]

UK CAA

The UK Civil Aviation Authority, no longer part of EASA following the UK's withdrawal from the European Union, issued its own airworthiness directive on January 27, 2021, mirroring EASA's additional requirements.[258]

Transport Canada

Transport Canada accepted FAA's MAX certification in June 2017 under a bilateral agreement.[259] Former Canadian Minister of Transport Marc Garneau said in March 2019, that Transport Canada would do its own certification of Boeing's software update "even if it's certified by the FAA.".[259] On October 4, 2019, the head of civil aviation for Transport Canada, said that global regulators are considering the requirements for the 737 MAX to fly again, weighing in the "startle factors" that can overwhelm pilots lacking sufficient exposure in simulation scenarios. He also said that Transport Canada raised questions over the architecture of the angle of attack system.[260] On November 19, 2019, an engineering manager in aircraft integration and safety assessment at Transport Canada emailed FAA, EASA and Brazil's National Civil Aviation Agency, calling for removal of key software from the 737 MAX by stating "The only way I see moving forward at this point is that Boeing's MCAS system has to go," although the views were at the working level and had not been subject to systematic review by Transport Canada.[261]

On August 20, 2020, Transport Canada announced that it would be conducting its own flight tests the following week, as part of its independent review aimed at validating key areas of the FAA certification. Transport Canada confirmed it was working with EASA and the Brazilian regulator ANAC, in the Joint Operational Evaluation Board (JOEB), which is set to evaluate minimum pilot training requirements in mid-September.[262] EASA concluded a series of recertification flights on September 11.[263]

Following the FAA's clearance to resume flights in the U.S., Transport Canada indicated that its own recertification process was ongoing, and that it intends to mandate additional pre-flight and in-flight procedures as well as differences in pilot training requirements. It did not indicate a timeline, though it did state that it expected to complete the process "very soon", as of November 2020.[264]

In December 2020, in addition to the changes required by the FAA, Transport Canada mandated the possibility for the pilot to disable the stick shaker when it is erroneously activated.[265] On January 18, 2021, it announced the return to service of the MAX in Canadian airspace from January 20, by lifting the NOTAM prohibiting its commercial operation.[8]

Indian DGCA

India's regulator, Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), will conduct its own validation tests of the MAX before authorizing it in India's airspace. Arun Kumar, Director General of DGCA, said India will adopt a "wait and watch" policy and not hurry to reauthorize the plane to fly. He also said an independent validation will be performed to ensure safety and MAX pilots will have to train on a simulator. India's SpiceJet has already received 13 MAX jets and has 155 more on order.[266][267]

On 26 August 2021, the DGCA lifted its ban on the 737 MAX in India, with operational rules based on the EASA's directive issued in February 2021.[268][269]

UAE's GCAA

The UAE's director general of the General Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA), Said Mohammed al-Suwaidi, announced GCAA will conduct its own assessment, rather than follow the FAA. The UAE regulator had yet not seen Boeing's fixes in detail.[270] He did not expect the 737 MAX to be back in service in 2019.[271]

On November 22, 2020, following the recertification by FAA, the GCAA had established a Return to Service Committee on Boeing 737 MAX that included specialists from the required areas who were working with their counterparts in the FAA and the EASA. The GCAA would issue a Safety Decision stipulating technical requirements to ensure a safe return to service of the MAX aircraft with the corresponding certification timelines.[272] UAE carrier flydubai is one of the biggest customers of the MAX aircraft, having ordered 250 of the jets since 2013. It operated 13 MAX 8 and MAX 9s.[273]

Australian CASA

Australia's Civil Aviation Safety Authority said that the FAA decision would be an important factor in allowing the MAX to fly, but CASA will make its own decision.[274] In October 2019 SilkAir flew its six 737 MAXs from Singapore to Alice Springs Airport for storage during Singapore's wet season.[275]

On February 26, 2021, the Australian Civil Aviation Safety Authority lifted its ban on the MAX, accepting the return-to-service requirements set by the FAA. Australia is the first nation in the Asia-Pacific region to clear the aircraft to return to service.[276]

Brazilian ANAC

According to the first Brazilian government statement on the MAX issue, the National Civil Aviation Agency of Brazil (ANAC) had been working closely with the FAA on getting the airplane back into service by the end of 2019. Brazil's largest domestic airline, Gol Transportes Aéreos, is a major MAX customer with an order over 100 aircraft.[277]

On November 25, 2020, less than a week after the FAA cleared the MAX to return to service in the U.S., ANAC withdrew its Airworthiness Directive that had ordered the grounding of the aircraft.[278]

IATA

On November 25, 2020, the IATA called on all global regulators to authorize the return of the MAX as soon as possible.[257]

Projections

In November 2019, financial analysts forecast a jet surplus that could result when the MAX does return to service; new aircraft will be delivered while airlines move stand-in aircraft back into storage.[279]

Boeing initially hoped that flights could resume by July 2019;[280] by June 3, Muilenburg expected to have the planes flying by the end of 2019 but declined to provide a timeline.[281] On July 18, Boeing reaffirmed Muilenburg's prediction, hoping to return the MAX to flight during the fourth quarter of 2019. Boeing indicated that this was its best estimate and that the date could still slip.[282]

By July 2019, United Airlines purchased 19 used 737-700s to fill in for MAX aircraft, to be delivered in December 2019.[283] United had expected to receive 30 MAX aircraft by the end of 2019 and a further 28 in 2020.[284]

In September 2019, Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg stated that the MAX might return in phases around the world due to the current state of regulatory divide on approving the airplane.[285] Later that same month, Boeing told its suppliers that the plane could return to service by November.[286] On November 11, 2019, the company stated that deliveries would resume in December 2019 and commercial flights in January 2020.[287][288][289] In January 2020, Boeing said it was not expecting the airplane's recertification until mid 2020.[290]

On January 14, 2020, American Airlines cancelled more of its MAX flights until June 3.[291] On January 16, Southwest Airlines removed the MAX from its schedule until June 6, to allow pilots to spend time in simulators as newly recommended.[292] On January 22, United Airlines announced that it was not expecting to return the MAX to service until after the peak summer season.[293]

By late April, Southwest Airlines had removed the MAX from its schedule until October 30, based on Boeing's "recent communication on the MAX return to service date". At that point, Boeing hoped to obtain regulatory approval in August, though sources expected that to be pushed back to the fall.[294]

At the end of October 2020, Boeing indicated that it expected recertification to occur before the end of the year, and anticipated that about half of the 450 aircraft currently stockpiled would be delivered in 2021.[295] In December 2020, American Airlines operated the first public flight since the grounding: a demonstration flight for journalists, to regain public trust.[296]

Certification of forthcoming MAX variants

The 737-10 has yet to be certified and is expected to be subject to additional requirements, including in particular an "angle-of-attack integrity enhancement" that will subsequently be retrofitted to existing variants. Improvements to the crew alerting system are also expected to be mandated.[297]

On March 31, 2021, the FAA certified the high-density variant of the 737 MAX 8 for low-cost carriers, the MAX 8-200. They have identified the variant as being "functionally equivalent" to the MAX 8 and "operationally suitable". Europe's EASA is expected to follow suit. Ryanair will be the first and primary operator of the variant; Vietnam's VietJet Air also has a sizable order. The first jet for Ryanair is expected to be delivered in April, and in the peak summer season, the carrier will likely have 16 jets in their fleet, according to the CEO Michael O'Leary.[298]

By July 2022, as it had about 640 orders, Boeing CEO David Calhoun thought the 737-10 could be cancelled as it had a certification deadline by 2022 year-end before requiring adding a crew alerting system, leading to lower 737 commonality, unless a waiver is granted, a political decision of the US Congress.[299]

Notes

- install new flight control computer software and new display system software; incorporate certain Airplane Flight Manual flightcrew operating procedures; modify horizontal stabilizer trim wire routing installations; conduct an angle of attack sensor system test; and conduct an operational readiness flight

References

- "Boeing's 737 MAX Crisis: Coverage by The Seattle Times". The Seattle Times. December 15, 2019. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- Gates, Dominic; Miletich, Steve; Kamb, Lewis (October 2, 2019). "Boeing pushed FAA to relax 737 MAX certification requirements for crew alerts". The Seattle Times. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- Slotnick, David. "The DOJ is reportedly probing whether Boeing's chief pilot misled regulators over the 737 Max". Business Insider. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- "Inspector General report details how Boeing played down MCAS in original 737 MAX certification – and FAA missed it". The Seattle Times. June 30, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "FAA Probing Boeing's Alleged Pressure on Designated Inspectors". BNN Bloomberg. July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- "Final Committee Report on the Design, Development, and Certification of the Boeing 737 MAX". The House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. September 15, 2020. p. 141.

- Gates, Dominic (November 18, 2020). "Boeing 737 MAX can return to the skies, FAA says".

- "Transport Canada introduces additional requirements to allow for the return to service of the Boeing 737 MAX" (Press release). Transport Canada. January 18, 2021.

- "Boeing 737 Max cleared to fly in Europe after crashes". BBC News. January 27, 2021.

- Gates, Dominic (March 17, 2019). "Flawed analysis, failed oversight: How Boeing, FAA certified the suspect 737 MAX flight control system". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- "Boeing's 737 MAX takes wing with new engines, high hopes". The Seattle Times. January 29, 2016. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- Goold, Ian (November 8, 2017). "Boeing Forges Ahead with Flight-test Campaigns". AIN. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet No. A16WE" (PDF). FAA. March 8, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- "Boeing 737 MAX 8 Earns FAA Certification". Boeing. March 9, 2017. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet No.: IM.A.120" (PDF). EASA. March 27, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- Karp, Aaron (May 10, 2017). "Boeing suspends 737 MAX flights, cites 'potential' CFM LEAP-1B issue". Air Transport World. Aviation Week Network. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- Trimble, Stephen (May 16, 2017). "Boeing delivers first 737 Max". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on December 29, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- Trimble, Stephen (May 12, 2017). "Boeing resumes 737 Max 8 test flights". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- Robison, Peter; Levin, Alan (March 18, 2019). "Boeing Drops as Role in Vetting Its Own Jets Comes Under Fire". Fortune. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on March 19, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Stieb, Matt (March 17, 2019). "Report: The Regulatory Failures of the Boeing 737 MAX". New York. Archived from the original on March 20, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "Transport Canada Civil Aviation (TCCA) Operational Evaluation Report". www.tc.gc.ca. Government of Canada; Transport Canada; Safety and Security Group. January 9, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

The FAA has assigned the B-737 Pilot Type rating to all series of the Boeing 737, but have grouped the series similar to the TCCA pilot type ratings (B73A, B73B and B73C).

- Gates, Dominic (March 18, 2019). "Flawed analysis, failed oversight: How Boeing, FAA certified the suspect 737 MAX flight control system". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- Puckett, Jessica (September 17, 2019). "Boeing's 737 Max Has a Long Way to Go Before It Can Fly Again". Condé Nast Traveler. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Leggett, Theo (May 17, 2019). "What went wrong inside Boeing's cockpit?". BBC News Online.

- Thrush, Glenn (May 15, 2019). "F.A.A. Chief Defends Boeing Certification Process at House Hearing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- Baker, Mike (May 15, 2019). "FAA chief: Manuals should have told 737 MAX pilots more about Boeing's MCAS system". The Seattle Times. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

The FAA needs to fix its credibility problem. [Larsen said] The committee will work with the FAA as it rebuilds public and international confidence in its decisions, but our job is oversight and the committee will continue to take this role seriously.

- Woodyard, Chris. "'Jedi mind tricks': Boeing 737 Max emails show attempts to manipulate airlines, FAA". USA Today. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- "Fatal flaw in Boeing 737 Max traceable to one key late decision". The Irish Times. June 2, 2019.

- Laris, Michael; Duncan, Ian; Aratani, Lori (October 28, 2019). "FAA's lax oversight played part in Boeing 737 Max crashes, but agency is pushing to become more industry-friendly". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- "Test pilot at center of 737 Max investigation takes buyout from Southwest Airlines". Dallas News. August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Gollom, Mark; Shprintsen, Alex; Zalac, Frédéric (March 26, 2019). "737 Max flight manual may have left MCAS information on 'cutting room floor'". CBC.ca. Retrieved June 27, 2019.