Serum protein electrophoresis

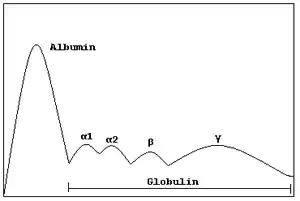

Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP or SPE) is a laboratory test that examines specific proteins in the blood called globulins.[1] The most common indications for a serum protein electrophoresis test are to diagnose or monitor multiple myeloma, a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance (MGUS), or further investigate a discrepancy between a low albumin and a relatively high total protein. Unexplained bone pain, anemia, proteinuria, chronic kidney disease, and hypercalcemia are also signs of multiple myeloma, and indications for SPE.[2] Blood must first be collected, usually into an airtight vial or syringe. Electrophoresis is a laboratory technique in which the blood serum (the fluid portion of the blood after the blood has clotted) is applied to either an acetate membrane soaked in a liquid buffer,[3][4] or to a buffered agarose gel matrix, or into liquid in a capillary tube, and exposed to an electric current to separate the serum protein components into five major fractions by size and electrical charge: serum albumin, alpha-1 globulins, alpha-2 globulins, beta 1 and 2 globulins, and gamma globulins.

| Serum protein electrophoresis | |

|---|---|

Normal serum protein electrophoresis diagram with legend of different zones. | |

| MeSH | D001797 |

Acetate or gel electrophoresis

Proteins are separated by both electrical forces and electroendoosmostic forces. The net charge on a protein is based on the sum charge of its amino acids, and the pH of the buffer. Proteins are applied to a solid matrix such as an agarose gel, or a cellulose acetate membrane in a liquid buffer, and electric current is applied. Proteins with a negative charge will migrate towards the positively charged anode. Albumin has the most negative charge, and will migrate furthest towards the anode. Endoosmotic flow is the movement of liquid towards the cathode, which causes proteins with a weaker charge to move backwards from the application site. Gamma proteins are primarily separated by endoosmotic forces.[5] The drawing of the electrophoretic bands provided by the laboratory may be difficult to remember, and medical students, residents, nurses, and non-specialized medical practitioners may find visual mnemonics useful to recall the five main bands and the shape of normal serum electrophoresis.[6]

Capillary electrophoresis

In capillary electrophoresis, there is no solid matrix. Proteins are separated primarily by strong electroendosmotic forces. The sample is injected into a capillary with a negative surface charge. A high current is applied, and negatively charged proteins such as albumin try to move towards the anode. Liquid buffer flows towards the cathode, and drags proteins with a weaker charge.[7][8]

Serum protein fractions

Albumin

Albumin is the major fraction in a normal SPEP. A fall of 30% is necessary before the decrease shows on electrophoresis. Usually a single band is seen. Heterozygous individuals may produce bisalbuminemia – two equally staining bands, the product of two genes. Some variants give rise to a wide band or two bands of unequal intensity but none of these variants is associated with disease.[9] Increased anodic mobility results from the binding of bilirubin, nonesterified fatty acids, penicillin and acetylsalicylic acid, and occasionally from tryptic digestion in acute pancreatitis.

Absence of albumin, known as analbuminaemia, is rare. A decreased level of albumin, however, is common in many diseases, including liver disease, malnutrition, malabsorption, protein-losing nephropathy and enteropathy.[10]

Albumin – alpha-1 interzone

Even staining in this zone is due to alpha-1 lipoprotein (high density lipoprotein – HDL). Decrease occurs in severe inflammation, acute hepatitis, and cirrhosis. Also, nephrotic syndrome can lead to decrease in albumin level; due to its loss in the urine through a damaged leaky glomerulus. An increase appears in severe alcoholics and in women during pregnancy and in puberty.

The high levels of AFP that may occur in hepatocellular carcinoma may result in a sharp band between the albumin and the alpha-1 zone.

Alpha-1 zone

Orosomucoid and antitrypsin migrate together but orosomucoid stains poorly so alpha 1 antitrypsin (AAT) constitutes most of the alpha-1 band. Alpha-1 antitrypsin has an SG group and thiol compounds may be bound to the protein altering their mobility. A decreased band is seen in the deficiency state. It is decreased in the nephrotic syndrome[11] and absence could indicate possible alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. This eventually leads to emphysema from unregulated neutrophil elastase activity in the lung tissue. The alpha-1 fraction does not disappear in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, however, because other proteins, including alpha-lipoprotein and orosomucoid, also migrate there. As a positive acute phase reactant, AAT is increased in acute inflammation.

Bence Jones protein may bind to and retard the alpha-1 band.

Alpha-1 – alpha-2 interzone

Two faint bands may be seen representing alpha 1-antichymotrypsin and vitamin D binding protein. These bands fuse and intensify in early inflammation due to an increase in alpha 1-antichymotrypsin, an acute phase protein.

Alpha-2 zone

This zone consists principally of alpha-2 macroglobulin (AMG or A2M) and haptoglobin. There are typically low levels in haemolytic anaemia (haptoglobin is a suicide molecule which binds with free haemoglobin released from red blood cells and these complexes are rapidly removed by phagocytes). Haptoglobin is raised as part of the acute phase response, resulting in a typical elevation in the alpha-2 zone during inflammation. A normal alpha-2 and an elevated alpha-1 zone is a typical pattern in hepatic metastasis and cirrhosis.

Haptoglobin/haemoglobin complexes migrate more cathodally than haptoglobin as seen in the alpha-2 – beta interzone. This is typically seen as a broadening of the alpha-2 zone.

Alpha-2 macroglobulin may be elevated in children and the elderly. This is seen as a sharp front to the alpha-2 band. AMG is markedly raised (10-fold increase or greater) in association with glomerular protein loss, as in nephrotic syndrome. Due to its large size, AMG cannot pass through glomeruli, while other lower-molecular weight proteins are lost. Enhanced synthesis of AMG accounts for its absolute increase in nephrotic syndrome. Increased AMG is also noted in rats with no albumin indicating that this is a response to low albumin rather than nephrotic syndrome itself[12]

AMG is mildly elevated early in the course of diabetic nephropathy.

Alpha-2 - beta interzone

Cold insoluble globulin forms a band here which is not seen in plasma because it is precipitated by heparin. There are low levels in inflammation and high levels in pregnancy.

Beta lipoprotein forms an irregular crenated band in this zone. High levels are seen in type II hypercholesterolaemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and in the nephrotic syndrome.

Beta zone

Transferrin and beta-lipoprotein (LDL) comprises the beta-1. Increased beta-1 protein due to the increased level of free transferrin is typical of iron deficiency anemia, pregnancy, and oestrogen therapy. Increased beta-1 protein due to LDL elevation occurs in hypercholesterolemia. Decreased beta-1 protein occurs in acute or chronic inflammation.

Beta-2 comprises C3 (complement protein 3). It is raised in the acute phase response. Depression of C3 occurs in autoimmune disorders as the complement system is activated and the C3 becomes bound to immune complexes and removed from serum. Fibrinogen, a beta-2 protein, is found in normal plasma but absent in normal serum. Occasionally, blood drawn from heparinized patients does not fully clot, resulting in a visible fibrinogen band between the beta and gamma globulins.

Beta-gamma interzone

C-reactive protein is found in between the beta and gamma zones producing beta/gamma fusion. IgA has the most anodal mobility and typically migrates in the region between the beta and gamma zones also causing a beta/gamma fusion in patients with cirrhosis, respiratory infection, skin disease, or rheumatoid arthritis (increased IgA). Fibrinogen from plasma samples will be seen in the beta gamma region. Fibrinogen, a beta-2 protein, is found in normal plasma but absent in normal serum. Occasionally, blood drawn from heparinized patients does not fully clot, resulting in a visible fibrinogen band between the beta and gamma globulins.

Gamma zone

The immunoglobulins or antibodies are generally the only proteins present in the normal gamma region. Of note, any protein migrating in the gamma region will be stained and appear on the gel, which may include protein contaminants, artifacts, or certain medications. Depending on whether an agarose or capillary method is used, interferences vary. Immunoglobulins consist of heavy chains (μ, δ, γ, α, and ε) and light chains (κ and λ). A normal gamma zone should appear as a smooth 'blush', or smear, with no asymmetry or sharp peaks.[13] The gamma globulins may be elevated (hypergammaglobulinemia), decreased (hypogammaglobulinaemia), or have an abnormal peak or peaks. Note that immunoglobulins may also be found in other zones; IgA typically migrates in the beta-gamma zone, and in particular, pathogenic immunoglobulins may migrate anywhere, including the alpha regions.

Hypogammaglobulinaemia is easily identifiable as a "slump" or decrease in the gamma zone. It is normal in infants. It is found in patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. IgA deficiency occurs in 1:500 of the population, as is suggested by a pallor in the gamma zone. Of note, hypogammaglobulinema may be seen in the context of MGUS or multiple myeloma.

If the gamma zone shows an increase the first step in interpretation is to establish if the region is narrow or wide. A broad "swell-like" manner (wide) indicates polyclonal immunoglobulin production. If it is elevated in an asymmetric manner or with one or more peaks or narrow "spikes" it could indicate clonal production of one or more immunoglobulins,[14]

Polyclonal gammopathy is indicated by a "swell-like" elevation in the gamma zone, which typically indicates a non-neoplastic condition (although is not exclusive to non-neoplastic conditions). The most common causes of polyclonal hypergammaglobulinaemia detected by electrophoresis are severe infection, chronic liver disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and other connective tissue diseases.

A narrow spike is suggestive of a monoclonal gammopathy, also known as a restricted band, or "M-spike". To confirm that the restricted band is an immunoglobulin, follow up testing with immunofixation, or immunodisplacement/immunosubtraction (capillary methods) is performed. Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAb), also migrate in this region and may be misinterpreted as a monoclonal gammopathy, and may also be identified by immunofixation or immunodisplacement/immunosubtraction as they are structurally comparable to human immunoglobulins.[15] The most common cause of a restricted band is an MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance), which, although a necessary precursor, only rarely progresses to multiple myeloma. (On average, 1%/year.)[16] Typically, a monoclonal gammopathy is malignant or clonal in origin, Myeloma being the most common cause of IgA and IgG spikes. chronic lymphatic leukaemia and lymphosarcoma are not uncommon and usually give rise to IgM paraproteins. Note that up to 8% of healthy geriatric patients may have a monoclonal spike.[17] Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia (IgM), monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), amyloidosis, plasma cell leukemia and solitary plasmacytomas also produce an M-spike.

Oligoclonal gammopathy is indicated by one or more discrete clones.

Lysozyme may be seen as a band cathodal to gamma in myelomonocytic leukaemia in which it is released from tumour cells.

References

- Jenkins, Margaret A. (1999). "Serum Protein Electrophoresis". Clinical Applications of Capillary Electrophoresis. Methods in Molecular Medicine. Vol. 27. pp. 11–20. doi:10.1385/1-59259-689-4:11. ISBN 1-59259-689-4. PMID 21374283.

- Harris, Neil S.; Winter, William E. (2012). Multiple Myeloma and Related Serum Protein Disorders: An Electrophoretic Guide. Demos Medical. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-933864-75-4.

- Kaplan, A; Savory, J (1965). "Evaluation of a cellulose-acetate electrophoresis system for serum protein fractionation". Clinical Chemistry. 11 (10): 937–42. doi:10.1093/clinchem/11.10.937. PMID 4158264.

- Chemistry/ "Evaluation of a cellulose-acetate electrophoresis system for serum protein fractionation". Clinical Chemistry. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - Harris 2012, pp. 9–16.

- Visual mnemonics for serum protein electrophoresis https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3402/meo.v18i0.22585

- Harris, 2012 & pages 117–123.

- Keren, David F. (2003). Protein Electrophoresis in Clinical Diagnosis. Hodder Arnold. pp. 1–14. ISBN 0340-81213-3.

- Hoang, Mai P; Baskin, Leland B; Wians, Frank H (1999). "Bisalbuminuria in an adult with bisalbuminemia and nephrotic syndrome". Clinica Chimica Acta. 284 (1): 101–7. doi:10.1016/S0009-8981(99)00054-6. PMID 10437648.

- Peralta, Ruben; Rubery, Brad A (July 30, 2012). Pinsky, Michael R; Sharma, Sat; Talavera, Francisco; Manning, Harold L; Rice, Timothy D (eds.). "Hypoalbuminemia". Medscape. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Longsworth, LG; Macinnes, DA (1 January 1940). "An Electrophoretic Study of Nephrotic Sera and Urine". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 71 (1): 77–82. doi:10.1084/jem.71.1.77. PMC 2135007. PMID 19870946.

- Stevenson, FT; Greene, S; Kaysen, GA (January 1998). "Serum alpha 2-macroglobulin and alpha 1-inhibitor 3 concentrations are increased in hypoalbuminemia by post-transcriptional mechanisms". Kidney International. 53 (1): 67–75. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00734.x. PMID 9453001.

- Keren 2003, pp. 93–97.

- Tuazon, Sherilyn Alvaran; Scarpaci, Anthony P (May 11, 2012). Staros, Eric B (ed.). "Serum protein electrophoresis". Medscape. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- McCudden, C. (2016). "Monitoring multiple myeloma patients treated with daratumumab: teasing out monoclonal antibody interference". Clin Chem Lab Med. 54 (6): 1095–104. doi:10.1515/cclm-2015-1031. PMID 27028734.

- Harris 2012, p. 60.

- Wadhera, Rishi K.; Rajkumar, S. Vincent (2010). "Prevalence of Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance: A Systematic Review". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 85 (10): 933–42. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0337. PMC 2947966. PMID 20713974.

External links

- Protein electrophoresis at Lab Tests Online

- Visual mnemonics for serum protein electrophoresis