Black Paintings

The Black Paintings (Spanish: Pinturas negras) is the name given to a group of 14 paintings by Francisco Goya from the later years of his life, likely between 1819 and 1823. They portray intense, haunting themes, reflective of both his fear of insanity and his bleak outlook on humanity. In 1819, at the age of 72, Goya moved into a two-story house outside Madrid that was called Quinta del Sordo (Deaf Man's Villa). Although the house had been named after the previous owner, who was deaf, Goya too was nearly deaf at the time as a result of an unknown illness he had suffered when he was 46. The paintings originally were painted as murals on the walls of the house, later being "hacked off" the walls and attached to canvas by owner Baron Frédéric Émile d'Erlanger.[1] They are now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.[2]

After the Napoleonic Wars and the internal turmoil of the changing Spanish government, Goya developed an embittered attitude toward mankind. He had an acute, first-hand awareness of panic, terror, fear and hysteria. He had survived two near-fatal illnesses, and grew increasingly anxious and impatient in fear of relapse. The combination of these factors is thought to have led to his production of the Black Paintings. Using oil paints and working directly on the walls of his dining and sitting rooms, Goya created works with dark, disturbing themes. The paintings were not commissioned and were not meant to leave his home. It is likely that the artist never intended the works for public exhibition: "these paintings are as close to being hermetically private as any that have ever been produced in the history of Western art."[3]

Goya did not give titles to the paintings, or if he did, he never revealed them. Most names used for them are designations employed by art historians.[4] Initially, they were catalogued in 1828 by Goya's friend, Antonio Brugada.[5] The series is made up of 14 paintings: Atropos (The Fates), Two Old Men, Two Old Ones Eating Soup, Fight with Cudgels, Witches' Sabbath, Men Reading, Judith and Holofernes, A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, Man Mocked by Two Women, Pilgrimage to the Fountain of San Isidro, The Dog, Saturn Devouring His Son, La Leocadia, and Asmodea.

Images of the Black Paintings

.jpg.webp) (Saturno devorando a su hijo), Saturn Devouring His Son, 1819–1823

(Saturno devorando a su hijo), Saturn Devouring His Son, 1819–1823 (El perro), The Dog, 1819–1823

(El perro), The Dog, 1819–1823 (Dos viejos/Un viejo y un fraile), Two Old Men, 1819–1823

(Dos viejos/Un viejo y un fraile), Two Old Men, 1819–1823 (Hombres leyendo), Men Reading, 1819–1823

(Hombres leyendo), Men Reading, 1819–1823.jpg.webp) (Judith y Holofernes), Judith and Holofernes, 1819–1823

(Judith y Holofernes), Judith and Holofernes, 1819–1823 (Dos mujeres y un hombre), Man Mocked by Two Women, 1819–1823

(Dos mujeres y un hombre), Man Mocked by Two Women, 1819–1823.jpg.webp) (Una manola/La Leocadia), La Leocadia, 1819–1823

(Una manola/La Leocadia), La Leocadia, 1819–1823 Heads in a Landscape (Cabezas en un paisaje, possibly the fifteenth Black Painting)

Heads in a Landscape (Cabezas en un paisaje, possibly the fifteenth Black Painting)

(Duelo a garrotazos), Fight with Cudgels, 1819–1823

(Duelo a garrotazos), Fight with Cudgels, 1819–1823 (Dos viejos comiendo sopa), Two Old Ones Eating Soup, 1819–1823

(Dos viejos comiendo sopa), Two Old Ones Eating Soup, 1819–1823 (Peregrinación a la fuente de San Isidro/Procesión del Santo Oficio), Pilgrimage to the Fountain of San Isidro, 1819–1823

(Peregrinación a la fuente de San Isidro/Procesión del Santo Oficio), Pilgrimage to the Fountain of San Isidro, 1819–1823 (El Gran Cabrón/Aquelarre), Witches' Sabbath, 1819–1823

(El Gran Cabrón/Aquelarre), Witches' Sabbath, 1819–1823 (La romería de San Isidro), A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, 1819–1823

(La romería de San Isidro), A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, 1819–1823.jpg.webp) (Vision fantástica/Asmodea), Asmodea, 1819–1823

(Vision fantástica/Asmodea), Asmodea, 1819–1823 (Átropos/Las Parcas), Atropos, 1819–1823

(Átropos/Las Parcas), Atropos, 1819–1823

History

Goya acquired the Quinta del Sordo villa on the banks of the River Manzanares, near the Segovia bridge and with views over the plains of San Isidro, in February 1819. It has been suggested that he bought the house to escape public attention; he lived there with his companion and maid Leocadia Weiss, even though she was still married to Isidoro Weiss. It is thought that Goya had a relationship with her and possibly a daughter, Rosario. It is not known exactly when Goya began painting the Black Paintings. He may have started work on the murals between February and November 1819 when he fell seriously ill as testified by the disturbing Self-portrait with Dr Arrieta (1820). What is known is that the murals were painted over rural scenes containing small figures, as Goya made use of the landscapes in some of his murals such as Fight with Cudgels.

If the light-toned bucolic paintings are also the works of Goya, it may be that his illness and the turbulent events of the Trienio Liberal led him to paint over them.[7] Bozal has suggested that those paintings also were painted by Goya as this is the only way to understand why he reused them. However, Nigel Glendinning assumes that the paintings "already adorned the walls of Quinta del Sordo when he bought it."[8] Whatever the truth of the matter, the Black Paintings murals probably date from 1820 and were likely finished no later than 1823 when Goya, departing for Bordeaux, left the villa to his grandson Mariano,[9] perhaps due to fear of reprisals after the fall of Rafael Riego and the republican army. Mariano de Goya transferred ownership of the villa to his father Javier de Goya in 1830.

The slow process of transferring the murals onto canvas began in 1874. The walls of the villa had been covered in wallpaper and Goya had painted on top of this layer which was carefully removed and reapplied to canvas. This work was carried out under the supervision of Salvador Martínez Cubells at the request of Baron Émile d’Erlanger,[10] a French banker of German origins, who wanted to sell them at the Paris World's Fair in 1878. However, in 1881 the baron donated the paintings to the Spanish state and they are now on display at the Museo del Prado.[11]

Original setting

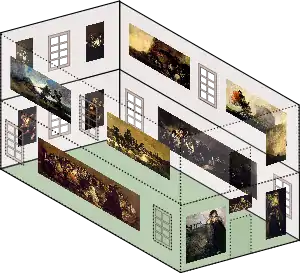

Antonio Brugada's inventory mentions seven murals on the ground floor and eight on the top floor.[12] However, only fourteen paintings arrived at the Museo del Prado. Charles Yriarte also describes an additional painting to those currently known to be in the collection; he indicates that when he visited the villa in 1867, it had already been removed from the wall and taken to the Marquis of Salamanca's Vista Alegre Palace. Many critics consider that because of its size and theme the missing painting must be the one identified as Heads in a landscape (New York, collection Stanley Moss).[13]

The other problem regarding the paintings' location revolves around Two Old Ones Eating Soup; there is uncertainty whether it was painted on a lintel in the upper or lower floor. Leaving this aside, the original distribution of the murals in Quinta del Sordo was as follows.[14]

The ground floor was a rectangular space. On the two long sides there were two windows near the shorter walls. Between these windows, there were two large murals in the form of landscapes: A Pilgrimage to San Isidro on the right when facing the murals and Witches' Sabbath on the left. At the back, on the smaller wall opposite the entrance, there was a window in the centre with Judith and Holofernes on the right and Saturn Devouring His Son on the left. La Leocadia was located on one side of the door (opposite Saturn) and Two Old Men was opposite Judith.[15]

The first floor was the same size as the ground floor, although there was only one central window in the long walls with a mural on each side. The right-hand wall as one entered contained Asmodea nearest to the entrance with Procession of the Holy Office beyond the window. On the left were Atropos and Fight with Cudgels respectively. On the short wall at the back it was possible to see Man Mocked by Two Women on the right and Men Reading on the left. To the right of the door was The Dog and to the left Heads in a landscape.

Two Old Ones Eating Soup would have been above one of the doors; Glendinning has suggested that it was above the door on the ground floor due to the design of the painted paper that appears in Laurent's photograph of the mural.[16]

.jpg.webp) (Una manola/La Leocadia), La Leocadia, 1819–1823

(Una manola/La Leocadia), La Leocadia, 1819–1823 (El Gran Cabrón/Aquelarre), Witches' Sabbath, 1819–1823

(El Gran Cabrón/Aquelarre), Witches' Sabbath, 1819–1823.jpg.webp) (Saturno devorando a su hijo), Saturn Devouring His Son, 1819–1823

(Saturno devorando a su hijo), Saturn Devouring His Son, 1819–1823.jpg.webp) (Judith y Holofernes), Judith and Holofernes, 1819–1823

(Judith y Holofernes), Judith and Holofernes, 1819–1823 (La romería de San Isidro), A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, 1819–1823

(La romería de San Isidro), A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, 1819–1823.jpg.webp) (Vision fantástica/Asmodea), Asmodea, 1819–1823

(Vision fantástica/Asmodea), Asmodea, 1819–1823 (Peregrinación a la fuente de San Isidro/Procesión del Santo Oficio), Pilgrimage to the Fountain of San Isidro, 1819–1823

(Peregrinación a la fuente de San Isidro/Procesión del Santo Oficio), Pilgrimage to the Fountain of San Isidro, 1819–1823 (Dos viejos/Un viejo y un fraile), Two Old Men, 1819–1823

(Dos viejos/Un viejo y un fraile), Two Old Men, 1819–1823 (Átropos/Las Parcas), Atropos, 1819–1823

(Átropos/Las Parcas), Atropos, 1819–1823 (Duelo a garrotazos), Fight with Cudgels, 1819–1823

(Duelo a garrotazos), Fight with Cudgels, 1819–1823 (Hombres leyendo), Men Reading, 1819–1823

(Hombres leyendo), Men Reading, 1819–1823 (Dos mujeres y un hombre), Man Mocked by Two Women, 1819–1823

(Dos mujeres y un hombre), Man Mocked by Two Women, 1819–1823 (El perro), The Dog, 1819–1823

(El perro), The Dog, 1819–1823 Heads in a Landscape (Cabezas en un paisaje, possibly the fifteenth Black Painting)

Heads in a Landscape (Cabezas en un paisaje, possibly the fifteenth Black Painting) (Dos viejos comiendo sopa), Two Old Ones Eating Soup, 1819–1823

(Dos viejos comiendo sopa), Two Old Ones Eating Soup, 1819–1823

Information may be gained from written testimonies regarding the distribution and the original state of the murals and also from an in situ photographic inventory carried out by Jean Laurent in 1874.[17] The photographs were commissioned by Baron d'Erlanger when he employed Martínez Cubells to transfer the paintings. Laurent's photographs were an accurate representation of the process of transferring the murals to canvas. The art historians Gregorio Cruzada Villaamil and Charles Yriarte had been concerned for at least ten years that increases in property prices in the area would result in the redevelopment of the villa and the loss of the paintings.[18]

It is possible to see in Laurent's photographs that the murals were framed with borders painted in classicist design as were the doors, windows and the frieze above the door. The walls were papered as was the custom in bourgeois and aristocratic residences, possibly with wallpaper from the Royal Painted Paper Factory which was patronized by Fernando VII. The paper on the ground floor was decorated with motifs of fruit and leaves and the first floor was decorated with geometrical drawings organized in diagonal lines. The photographs also document the state of the drawings before they were moved, showing, for example, that a large part of the right-hand side of Witches’ Sabbath has not been conserved, although it was transferred to canvas by Martínez Cubells.[19]

Photograph of Witches' Sabbath taken in 1874 by J. Laurent inside Quinta del Sordo |

Witches' Sabbath in its present form with cut edges |

Authenticity

Art historian Juan José Junquera has questioned the authenticity of the Black Paintings. In 2003, he came to the conclusion that they could not have been painted during Goya's lifetime.[20][21] According to Junquera, contemporary legal documents describe the Quinta del Sordo as a villa with only one floor, and the second storey was not added until after Goya's death. If the upper floor did not exist during Goya's time, then the Black Paintings (or at least those found on the upper floor) could not have been the work of Goya. He speculates that Goya's son Javier may have created the paintings, and Javier's son Mariano passed them off as the work of Goya for financial gain. Junquera's theory was rejected by Goya scholar Nigel Glendinning, who published an academic study defending the painting's authenticity and later held a lecture in Madrid restating his conviction. He made connections between the Black Paintings and other works by Goya (e.g. The Second of May 1808), and pointed to various documentary evidence, including an 1812 inventory of the artist's possessions catalogued by Goya's son, Javier, which included the work. Today, Museo del Prado recognise the Black Paintings as authentic.[22][23][24]

See also

Notes

- Lubow, Arthur (27 July 2003). "The Secret of the Black Paintings". The New York Times.

- "Explora la colección - Museo Nacional del Prado". www.museodelprado.es. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- Licht, 159

- Licht, 168

- There have been a number of suggestions for the names of these paintings. The earliest came from the inventory of the painter's assets made by Antonio Brugada after Goya's death.Museo del Prado, on-line educational series «Mirar un cuadro»: El aquelarre (in Spanish). Archived September 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "La Quinta de Goya". Descubrir el Arte (in Spanish). No. 201. November 2015. pp. 18–24. ISSN 1578-9047.

- Bozal, vol. 2, pp. 248–249.

- Glendinning (1993), p. 116.

- Arnaiz (1996), p. 19.

- Bozal, vol. 2, p. 247.

- Museo Nacional del Prado: Enciclopedia On-Line (in Spanish), retrieved 9 May 2009.

- Wilson-Bareau, Juliet. “Goya and the X Numbers: The 1812 Inventory and Early Acquisitions of ‘Goya’ Pictures.” Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 31, 1996, pp. 159–74. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/1512979. Accessed 23 Jan. 2023.

- "Heads in a landscape with commentary in Spanish". Archived from the original on 3 February 2012.

- There are on line virtual reconstructions of the space on: artarchive.com Archived 1 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine and theartwolf.com

- Fernández, G. (August 2006). "Goya: The Black Paintings". theartwolf.com. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- Glendinning, Nigel (1975). The Strange Translation of Goya's 'Black Paintings.'. The Burlington Magazine.

- Carlos Teixidor, "Fotografías de Laurent en la Quinta de Goya", in the magazine Descubrir el Arte, nº 154, December 2011, pages 48–54.

- María del Carmen Torrecillas Fernández, «Las pinturas de la Quinta del Sordo fotografiadas por J. Laurent», Boletín del Museo del Prado, volume XIII, number 31, 1992, page 57 onwards.

- ""Los frescos de Goya"', El Globo, Madrid, 26 July 1875. The newspaper outlined the fact that Martínez Cubells had successfully transferred Witches' Sabbath, "a beautiful canvas of more than five metres in length". This proves that Martínez Cubells transferred the whole painting and that it was later cut, possibly so that it would fit into a restricted space in Paris.

- Junquera, Juan José (2003). "Los Goya: de la Quinta a Burdeos y vuelta". Archivo Español de Arte (in Spanish). 76 (304): 353–370. doi:10.3989/aearte.2003.v76.i304.263. ISSN 0004-0428.

- Junquera, Juan José (2005). "La Quinta del Sordo en 1830: respuesta a Nigel Glendinning". Archivo Español de Arte (in Spanish). 78 (309): 83–105. doi:10.3989/aearte.2005.v78.i309.210. ISSN 0004-0428.

- Lubow, Arthur (27 July 2003). "The Secret of the Black Paintings". The New York Times.

- "Obituaries: Professor Nigel Glendinning". The Telegraph. 3 March 2013.

- Glendinning, Nigel (2004). "Las Pinturas Negras de Goya y la Quinta del Sordo. Precisiones sobre las teorías de Juan José Junquera". Archivo Español de Arte (in Spanish). 77 (307): 233–245. doi:10.3989/aearte.2004.v77.i307.229. ISSN 0004-0428.

Bibliography

- Arnaiz, José Manuel, Las pinturas negras de Goya, Madrid, Antiqvaria, 1996. ISBN 978-84-86508-45-6

- Benito Oterino, Agustín, La luz en la quinta del sordo: estudio de las formas y cotidianidad, Madrid, Universidad Complutense, 2002. ISBN 84-669-1890-6

- Bozal, Valeriano, Francisco Goya, vida y obra (2 vols.), Madrid, Tf., 2005. ISBN 84-96209-39-3.

- —, "Pinturas negras" de Goya, Tf. Editores, Madrid, Tf., 1997. ISBN 84-89162-75-1

- Ciofalo, John J. "Blackened Myths, Mirrors, and Memories". In: The Self-Portraits of Francisco Goya. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Connell, Evan S. Francisco Goya: A Life. New York: Counterpoint, 2004. ISBN 1-58243-307-0

- Cottom, Daniel. Unhuman Culture. University of Pennsylvania, 2006. ISBN 0-8122-3956-3

- Glendinning, Nigel, "The Strange Translation of Goya's Black Paintings", The Burlington Magazine, CXVII, 868, 1975.

- —, The Interpretation of Goya's Black Paintings, London, Queen Mary College, 1977.

- —, Goya y sus críticos, Madrid, Taurus, 1982.

- —, "Goya's Country House in Madrid. The Quinta del Sordo", Apollo, CXXIII, 288, 1986.

- —, Francisco de Goya, Madrid, Cuadernos de Historia 16 (col. "El arte y sus creadores", nº 30), 1993.

- Hagen, Rose-Marie y Rainer Hagen, Francisco de Goya, Colonia, Taschen, 2003. ISBN 3-8228-2296-5.

- Hughes, Robert. Goya. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004. ISBN 0-394-58028-1

- Licht, Fred. Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art. Universe Books, 1979. ISBN 0-87663-294-0

- Stoichita, Victor & Coderch, Anna Maria. Goya: The Last Carnival. London: Reakton books, 1999. ISBN 1-86189-045-1

- Wilson-Bareau, Juliet. Goya's Prints: the Tomás Harris Collection in the British Museum. London: British Museum Publications, 1981. ISBN 0-7141-0789-1

- Yriarte, Charles, Goya, sa vie, son oeuvre, Paris, Henri Plon, 1867.

External links

Media related to Pinturas negras at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pinturas negras at Wikimedia Commons