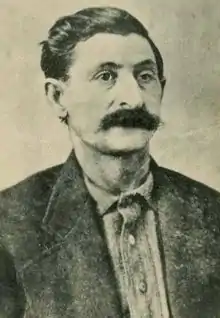

Big Nose George

George Parrott (20 March 1834 – 22 March 1881)[1] also known as Big Nose George, Big Beak Parrott, George Manuse, and George Warden, was a cattle rustler and highwayman in the American Wild West in the late 19th century.[2] His skin was made into a pair of shoes after his lynching and part of his skull was used as an ashtray.[3][4]

George Parrott | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 20, 1834 |

| Died | March 22, 1881 (aged 47) |

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | George Warden, George Manuse |

| Occupation(s) | Outlaw and cattle rustler |

| Known for | Banditry, murder, being made into a pair of shoes |

Outlaw

In 1878, Parrott and his gang murdered two law enforcement officers — Wyoming deputy sheriff Robert Widdowfield and Union Pacific detective Tip Vincent — after a bungled train robbery.[5] Widdowfield and Vincent had been ordered to track down Parrott's gang on August 19, 1878, following the attempted robbery on an isolated stretch of track near the Medicine Bow River.[3] The officers traced the outlaws to a camp at Rattlesnake Canyon, near Elk Mountain, where they were spotted by a gang lookout. The robbers stamped out the campfire and hid in a bush. When Widdowfield arrived at the scene, he realized the ashes of the fire were still hot. The gang ambushed the two lawmen, shooting Widdowfield in the face. Vincent tried to escape, but was shot before he made it out of the canyon. The gang took each man's weapons and one of their horses before covering up the bodies and fleeing the area.

The murder of the two lawmen was quickly discovered and a $10,000 reward was offered for the "apprehension of their murderers". This was later doubled to $20,000.[6]

In February 1879, "Big Nose" George and his cohorts were in Milestown (now Miles City, Montana). It was known around Milestown that a prosperous local merchant, Morris Cahn, would be taking money back east to buy stocks of merchandise. George, Charlie Burris and two others carried out a daring daylight robbery despite Morris Cahn traveling with a military convoy containing 15 soldiers, two officers, an ambulance, and a wagon from Fort Keogh, which was tasked to collect the army payroll. At a site approximately 10 miles (16 km) beyond the Powder River Crossing, near present-day Terry, Montana, there is a steep coulee (known ever since as "Cahn's Coulee"). Approaching the coulee over a five-mile (8 km) plateau, the soldiers, ambulance and the wagon became "strung out", creating large gaps between party members. The gang donned masks and stationed themselves at the bottom of the coulee, at a turn in the trail. The gang first surprised and then captured the lead element of soldiers, as well as the ambulance with Cahn and the officers. They waited and likewise captured the rear element of soldiers with the wagon. Cahn was robbed of an amount between $3,600 and $14,000, depending on who was doing the reporting.[7][8]

Arrest

In 1880 following the robbery of Cahn, Big Nose George Parrott and his second, Charlie Burris or "Dutch Charley", were arrested in Miles City by two local deputies, Lem Wilson and Fred Schmalsle. Big Nose and Charlie got drunk and boasted of killing the two Wyoming lawmen, thus identifying themselves as men with a price on their head.[7][9] Parrott was returned to Wyoming to face charges of murder.[9]

Lynching

Parrott was sentenced to hang on April 2, 1881, following a trial, but tried to escape while being held at a Rawlins, Wyoming jail. Parrott was able to wedge and file the rivets of the heavy shackles on his ankles, using a pocket knife and a piece of sandstone. On March 22, having removed his shackles, he hid in the washroom until jailor Robert Rankin entered the area. Using the shackles, Parrott struck Rankin over the head, fracturing his skull. Rankin managed to fight back, calling out to his wife, Rosa, for help at the same time. Grabbing a pistol, she managed to persuade Parrott to return to his cell.

News of the escape attempt spread through Rawlins and groups of people started making their way to the jail. While Rankin lay recovering, masked men with pistols burst into the jail. Holding Rankin at gunpoint, they took his keys, then dragged Parrott from his cell.[5][10]

Parrott's "rescuers" turned out to be townspeople, bringing Parrott out to a lynch mob of more than 200 people. The mob strung him up from a telegraph pole.[9][11]

Charlie Burris suffered a similar lynching not long after his capture;[6] having been transported by train to Rawlins, a group of locals found him hiding in a baggage compartment and proceeded to hang him on the crossbeam of another nearby telegraph pole.[12]

Desecration of remains

Doctors Thomas Maghee and John Eugene Osborne took possession of Parrott's body after his death, to study the outlaw's brain for clues to his criminality.[11][13] The top of Parrott's skull was crudely sawn off, and the cap was presented to 16-year-old Lillian Heath, then a medical assistant to Maghee. Heath became the first female doctor in Wyoming and is said to have used the cap as an ash tray, a pen holder and a doorstop.[10][14] A death mask was also created of Parrott's face, and skin from his thighs and chest was removed. The skin, including the dead man's nipples, was sent to a tannery in Denver, where it was made into a pair of shoes and a medical bag.[15][16] They were kept by Osborne, who wore the shoes to his inaugural ball after being elected as the first Democratic Governor of the State of Wyoming.[17][18] Parrott's dismembered body was stored in a whiskey barrel filled with a salt solution for about a year, while the experiments continued, until he was buried in the yard behind Maghee's office.[3][4]

Rediscovery

The death of Big Nose George faded into history over the years until May 11, 1950, when construction workers unearthed a whiskey barrel filled with bones while working on the Rawlins National Bank on Cedar Street in Rawlins. Inside the barrel was a skull with the top sawed off, a bottle of vegetable compound, and the shoes said to have been made from Parrott's thigh flesh.[19][20] Dr. Lillian Heath, then in her eighties, was contacted and her skull cap was sent to the scene. It was found to fit the skull in the barrel perfectly, and DNA testing later confirmed the remains were those of Big Nose George. Today the shoes made from the skin of Big Nose George are on permanent display at the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins, together with the bottom part of his skull and his earless death mask.[10] The shackles used during the hanging of the outlaw, as well as the skull cap, are on show at the Union Pacific Museum in Omaha, Nebraska. The medicine bag made from his skin has never been found.[2][4][9]

Legends

Many legends surround Big Nose George—including one which claims him as a member of Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch. Cassidy, however, would only have been 14 at the time of George's death, so this theory has been ruled out by historians. There is also speculation that he ran with the James brothers—with the flames of this rumor fanned by George himself.[15] During a pre-trial interview in 1880, Big Nose stated that his outlaw pal Frank McKinney had claimed to be Frank James. He also told investigators that another member, Sim Jan, was the gang leader—leading to wild rumors that Frank and Sim were the infamous James brothers, Frank and Jesse.[5]

However, it is generally agreed that Parrott was more of a run-of-the-mill horse thief and highwayman. His gang enjoyed a successful run of robbing pay wagons and stagecoaches of cash in the late 1870s, but a yearning for bigger profits led to the attempted train robbery and his hanging.[17]

See also

References

- estrepublicain.fr (in french). "The bandit from Montbéliard turned into shoes".

- francescacontreras.com (2006). "The Story of Big Nose George Parrott". Archived from the original on 2009-03-28. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Legends of America (2007). "Outlaw Big Nose George Becomes a Pair of Shoes in Rawlins". Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Chuck Woodbury (1997). "The crook who grew up to be a shoe". Archived from the original on 14 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Sunderland Echo (2009). "The ballad of Big Nose George". Archived from the original on 6 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Cullen, Tom (2003). Roamin' Wyomin'. Trafford Publishing. p. 211. ISBN 1-4120-0127-7.

- Amorette Allison, Terry Tribune (2011). "Cahn's Coulee Named After Misfortunate Incident". Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- Outlaw Tales of Montana: True Stories of Notorious Montana Bandits, Culprits and Crooks, Gary A. Wilson, Morris Book Publishing, LLC, 2003, ISBN 0-7627-2686-5, p. 116

- Time magazine (1950-05-22). "The return of Big Nose George". Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Wyoming Tales and Trails (2008). "The mortal remains of Big Nose George Parrott, Carbon County Museum". Archived from the original on 2009-04-05. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Original Hobo Nickel Society (2005). "Big Nose George". Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Davis, John W. (2006). Goodbye, Judge Lynch. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-8061-3774-6.

- Wyoming Bed and Breakfast website (2009). "Rawlins, Wyoming". Archived from the original on 2009-04-12. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Carbon County Museum (2007). "Big Nose George Parrott". Archived from the original on 2010-07-14. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Roadside America (2008). "Shoes Made From Big Nose George". Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Elk Mountain Hotel (2008). "Carbon County's Most Infamous Outlaw". Archived from the original on 6 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Carbon County Museum (2008). "Site of Big Nose George lynching". Archived from the original on 2010-07-14. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- John Taliaferro (2008). Charles M. Russell. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806134956. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- "Remains of Outlaw Found: Big Nose George Discovered in Whiskey Barrel". Beatrice Daily Sun. Beatrice, NB. May 14, 1950. p. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Patterson, Richard M. (1984). Historical atlas of the outlaw West. Big Earth Publishing. p. 213. ISBN 0-933472-89-7.