Xavier Bichat

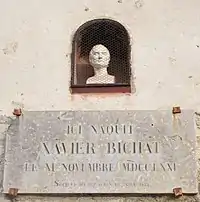

Marie François Xavier Bichat (/biːˈʃɑː/;[3] French: [biʃa]; 14 November 1771 – 22 July 1802)[4] was a French anatomist and pathologist, known as the father of modern histology.[5][lower-alpha 1] Although he worked without a microscope, Bichat distinguished 21 types of elementary tissues from which the organs of the human body are composed.[7] He was also "the first to propose that tissue is a central element in human anatomy, and he considered organs as collections of often disparate tissues, rather than as entities in themselves".[2]

Xavier Bichat | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Bichat by Pierre-Maximilien Delafontaine, 1799 | |

| Born | Marie François Xavier Bichat 14 November 1771 Thoirette, France |

| Died | 22 July 1802 (aged 30) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Known for | the concept of tissue[1] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Histology[2] Pathological anatomy[2] |

| Signature | |

| |

Although Bichat was "hardly known outside the French medical world" at the time of his early death, forty years later "his system of histology and pathological anatomy had taken both the French and English medical worlds by storm."[2] The Bichatian tissue theory was "largely instrumental in the rise to prominence of hospital doctors" as opposed to empiric therapy, as "diseases were now defined in terms of specific lesions in various tissues, and this lent itself to a classification and a list of diagnoses".[8]

Early life and training

Bichat was born in Thoirette, Franche-Comté.[9] His father was Jean-Baptiste Bichat, a physician who had trained in Montpellier and was Bichat's first instructor.[9] His mother was Jeanne-Rose Bichat, his father's wife and cousin.[10] He was the eldest of four children.[11] He entered the college of Nantua, and later studied at Lyon.[9] He made rapid progress in mathematics and the physical sciences, but ultimately devoted himself to the study of anatomy and surgery under the guidance of Marc-Antoine Petit (1766–1811), chief surgeon at the Hôtel-Dieu of Lyon.[9]

At the beginning of September 1793, Bichat was designated to serve as a surgeon with the Army of the Alps in the service of the surgeon Buget at the hospital of Bourg.[12][13] He went home in March 1794,[12] then moved to Paris, where he became a pupil of Pierre-Joseph Desault at the Hôtel-Dieu, "who was so strongly impressed with his genius that he took him into his house and treated him as his adopted son."[9] He took active part in Desault's work, at the same time pursuing his own research in anatomy and physiology.[9]

The sudden death of Desault in 1795 was a severe blow to Bichat.[9] His first task was to discharge the obligations he owed his benefactor by contributing to the support of his widow and her son and by completing the fourth volume of Desault's Journal de Chirurgie, which was published the following year.[9][14] In 1796, he and several other colleagues also formally founded the Société Médicale d'Émulation, which provided an intellectual platform for debating problems in medicine.[15]

Lecturing and research

In 1797, Bichat began a course of anatomical demonstrations, and his success encouraged him to extend the plan of his lectures, and boldly to announce a course of operative surgery.[9] At the same time, he was working to reunite and digest in one body the surgical doctrines which Desault had published in various periodical works;[9] of these he composed Œuvres chirurgicales de Desault, ou tableau de sa doctrine, et de sa pratique dans le traitement des maladies externes (1798–1799), a work in which, although he professes only to set forth the ideas of another, he develops them "with the clearness of one who is a master of the subject."[9]

In 1798, he gave in addition a separate course of physiology.[9] A dangerous attack of haemoptysis interrupted his labors for a time; but the danger was no sooner past than he plunged into new engagements with the same ardour as before.[9] Bichat's next book, Traité des membranes (Treatise on Membranes), included his doctrine of tissue pathology with a distinction of 21 different tissues.[16] As worded by A. S. Weber,

As soon as it appeared (January and February of 1800), it was regarded as a basic and classic text. It was cited in a host of other works, and almost all thinking men placed it with honor in their libraries.[13]

His next publication was the Recherches physiologiques sur la vie et la mort (Physiological Researches upon Life and Death, 1800), and it was quickly followed by his Anatomie générale (1801) in four volumes, the work which contains the fruits of his most profound and original researches.[9] He began another work, under the title Anatomie descriptive[17] (1801–1803), in which the organs were arranged according to his peculiar classification of their functions but lived to publish only the first two volumes.[9]

Final years and death

In 1800, Bichat was appointed physician to the Hôtel-Dieu. "He engaged in a series of examinations, with a view to ascertain the changes induced in the various organs by disease, and in less than six months he had opened above six hundred bodies. He was anxious also to determine with more precision than had been attempted before, the effects of remedial agents, and instituted with this view a series of direct experiments which yielded a vast store of valuable material. Towards the end of his life he was also engaged on a new classification of diseases.[9]"

On 8 July 1802, Bichat fell in a faint while descending a set of stairs at the Hôtel-Dieu.[18] He had been spending considerable time examining some macerated skin, "and from which, of course, putrid emanations were being sent forth",[19] during which he probably contracted typhoid fever;[18] "the next day he complained of a violent headache; that night, leeches were applied behind his ears; on the 10th, he took an emetic; on the 15th, he passed into a coma and became convulsive."[18] Bichat died on 22 July, aged 30.[4]

Jean-Nicolas Corvisart wrote to the first consul Napoleon Bonaparte:

Bichat vient de mourir sur un champ de bataille qui compte aussi plus d'une victime ; personne en si peu de temps n'a fait tant de choses et si bien. |

Bichat has fallen on a field of battle which numbers many a victim; no one has done in the same time so much and so well.[20] |

Ten days after this, the French government caused his name, together with that of Desault, to be inscribed on a memorial plaque at the Hôtel-Dieu.[21]

Bichat was first buried at Sainte-Catherine Cemetery. With the closing of the latter, his remains were transferred to Père Lachaise Cemetery on 16 November 1845, followed by "a cortège of upwards of two thousand persons" after a funeral service at Notre-Dame.[22]

Vitalist theory

Bichat is considered to have been a vitalist, though in no way an anti-experimentalist:[23]

Bichat moved from the tendency typical of the French vitalistic tradition to progressively free himself from metaphysics in order to combine with hypotheses and theories which accorded to the scientific criteria of physics and chemistry.[24]

According to Russell C. Maulitz, "of the Montpellier vitalists, the clearest influence on Bichat was probably Théophile de Bordeu (1722–1776), whose widely disseminated writings on the vitalistic interpretation of life fell early into Bichat's hands."[23]

In his Physiological Researches upon Life and Death (1800), Bichat defined life as "the totality of those set of functions which resist death",[25][26][27] adding:

Tel est en effet le mode d'existence des corps vivans, que tout ce qui les entoure tend à les détruire. |

Such is the mode of existence of living bodies that everything surrounding them tends to destroy them.[25] |

Bichat thought that animals exhibited vital properties which could not be explained through physics or chemistry.[16] In his Physiological Researches, he considered life to be separable into two parts: the organic life ("vie organique"; also sometimes called the vegetative system[7]) and the animal life ("vie animale", or animal system[7]).[28] The organic life was "the life of the heart, intestines, and the other inner organs."[29] As worded by Stanley Finger, "Bichat theorized that this life was regulated through the système des ganglions (the ganglionic nervous system), a collection of small independent 'brains' in the chest cavity."[29] In contrast, animal life "involved symmetrical, harmonious organs, such as the eyes, ears, and limbs. It included habit and memory, and was ruled by the wit and the intellect. This was the function of the brain itself, but it could not exist without the heart, the center of the organic life."[29]

According to A. S. Weber,

Bichat's use of the concept "vie animale" recalls the original Latin root anima or soul, the governor of movement, growth, nutrition and reason in the body in classical thought. Bichat's division is not new, and closely parallels the Platonic and later Christian division of body and soul, and the animism of Paracelsus, van Helmont, Georg Stahl and the Montpellier school of medicine.[30]

Legacy

Bichat's main contribution to medicine and physiology was his perception that the diverse body of organs contain particular tissues or membranes, and he described 21 such membranes, including connective, muscle, and nerve tissue.[7] As he explained in Anatomie générale,

La chimie a ses corps simples, qui forment, par les combinaisons diverses dont ils sont susceptibles, les corps composés [...]. De même, l'anatomie a ses tissus simples, qui, par leurs combinaisons [...] forment les organes. |

Bichat did not use a microscope because he distrusted it; therefore his analyses did not include any acknowledgement of cellular structure.[7] Nonetheless, he formed an important bridge between the organ pathology of Giovanni Battista Morgagni and the cell pathology of Rudolf Virchow.[31] Bichat "recognized disease as a localized condition that began in specific tissues."[8]

Michel Foucault regarded Bichat as the chief architect in developing the understanding of the human body as the origin of illness, redefining both conceptions of the body and disease.[32] Bichat's figure was of great importance to Arthur Schopenhauer, who wrote of the Recherches physiologiques as "one of the most profoundly conceived works in the whole of French literature."[33]

Honours

.jpg.webp)

A large bronze statue of Bichat by David d'Angers was erected in 1857 in the cour d'honneur of the École de Chirurgie in Paris, with the support of members of the Medical Congress of France which was held in 1845. Bichat is also represented on the Panthéon's pediment,[11] of which the bas-relief is D'Angers' work as well. The name of Bichat is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower. His name was given to the Bichat–Claude Bernard Hospital.

George Eliot enthusiastically recounted Bichat's career in her 1872 novel Middlemarch. In Madame Bovary (1856), Gustave Flaubert, himself the son of a prominent surgeon, wrote of a physician character who "belonged to the great school of surgery that sprang up around Bichat, to that generation, now extinct, of philosopher-practitioners who, cherishing their art with fanatical passion, exercised it with exaltation and sagacity."[34]

Gallery

Relief of Bichat on the pediment of the Panthéon

Relief of Bichat on the pediment of the Panthéon Statue by D'Angers in Bourg-en-Bresse

Statue by D'Angers in Bourg-en-Bresse_Wellcome_M0011378.jpg.webp) Portrait by Choquet

Portrait by Choquet_-_Veloso_Salgado.png.webp) Detail from Veloso Salgado's Medicine Through the Ages, NOVA University Lisbon

Detail from Veloso Salgado's Medicine Through the Ages, NOVA University Lisbon Bust at the University of Zaragoza College of Medicine

Bust at the University of Zaragoza College of Medicine

Notes

- Marcello Malpighi, the first person to scrutinize the human body with a microscope, is also considered the father of histology.[6]

References

- Proceedings of the Indian Science Congress. 1940. p. 249.

- "Xavier Bichat". LindaHall.org. 14 November 2018.

- "Bichat". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- Nafziger 2002, p. 46

- Banks 1993, p. 2

- Boyd & Sheldon 1977

- Roeckelein 1998, p. 78

- Shah 1994, p. 10

- Chisholm 1911

- Simmons 2002, p. 58

- Haigh 1984, p. 3

- Science and Medicine in France 1984, p. 52

- Weber 2000, p. 6

- Ersch 1797, p. 374

- Simmons 2002, p. 59

- Fye 1996, p. 761

- Bichat, Xavier (1771–1802) Auteur du texte (1812). Traité d'anatomie descriptive par Xav. Bichat. Tome 1 / ... Nouvelle édition.

- Haigh 1973, p. 25

- Pettigrew 1840, p. 6

- Rose 1857, p. 226

- Pettigrew 1840, p. 7

- The Medical Times 1846, p. 190

- Maulitz 2002, p. 15

- History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 2007, p. 238

- Florkin & Stotz 1986, p. 104

- Strauss 2012, p. 79

- Fernández-Medina 2018

- Weber 2000, pp. 6–7

- Finger 2001, p. 266

- Weber 2000, p. 7

- Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 1947, p. 459

- Miller 1993, pp. 130–131

- Crary 1992, p. 78

- Flaubert 1992, p. 262

Sources

- Banks, William J. (1993). Applied Veterinary Histology. Mosby-Year Book. ISBN 9780801666100.

- Boyd, William; Sheldon, Huntington (1 January 1977). An Introduction to the Study of Disease. Lea & Febiger. ISBN 9780812106008.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Florkin, Marcel; Stotz, Elmer Henry (1986). Comprehensive Biochemistry. Vol. 34. Elsevier Publishing Company. ISBN 9780444807762.

- Crary, Jonathan (1992). Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. MIT Press.

- Elaut, L. (July 1969). "The theory of membranes of F. X. Bichat and his predecessors". Sudhoffs Archiv. 53 (1): 68–76. ISSN 0039-4564. PMID 4241888.

- Ersch, J.S. (1797). La France litéraire contenant les auteurs francais de 1771 à 1796 (in French). Vol. 1.

- Finger, Stanley (2001). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514694-3. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Flaubert, Gustave (1992) [1856]. Madame Bovary. Translated by Wall, Geoffrey. Penguin Books.

- Fernández-Medina, Nicolás (2018). Life Embodied: The Promise of Vital Force in Spanish Modernity. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773554085.

- Fye, W. Bruce (1 September 1996). "Marie-François-Xavier Bichat". Clinical Cardiology. 19 (9): 760–761. doi:10.1002/clc.4960190918. ISSN 1932-8737. PMID 8875000.

- Haigh, Elizabeth (1984). Xavier Bichat and the Medical Theory of the Eighteenth Century. pp. 1–146. ISBN 085484046X. PMC 2557378. PMID 6398850.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Haigh, Elizabeth (1973). "Roots of the Vitalism of Xavier Bichat". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 49 (1): 72–86. PMID 1093586.

- History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. Vol. 29. 2007.

- Maulitz, Russell C. (2002). Morbid Appearances: The Anatomy of Pathology in the Early Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521524537.

- The Medical Times. Vol. 13. London. 1846.

- Miller, James (1993). The Passion of Michel Foucault. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-0-674-00157-2.

- Nafziger, George F. (2002). Historical Dictionary of the Napoleonic Era. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4092-8. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Pettigrew, Thomas Joseph (1840). Medical Portrait Gallery.

- Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. Vol. 40. 1947.

- Roeckelein, Jon E. (1998). Dictionary of Theories, Laws, and Concepts in Psychology. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30460-6. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Rose, Hugh James (1857). A New General Biographical Dictionary. Vol. IV. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lesch, John E. (1984). Science and Medicine in France. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674794009.

- Shah, Amil (1994). Solving the riddle of cancer: new genetic approaches to treatment. Dundurn. ISBN 9781459725515.

- Simmons, John G. (2002). Doctors and Discoveries: Lives That Created Today's Medicine. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-15276-6. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Strauss, Jonathan (13 February 2012). Human Remains: Medicine, Death, and Desire in Nineteenth-Century Paris. Fordham Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-3379-3. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- Weber, A. S. (2000). Nineteenth-Century Science: An Anthology. Broadview Press. ISBN 9781551111650.

Further reading

- Béclard, P. A. (1823). Additions to the General anatomy of Xavier Bichat. Richardson and Lord.

- Dobo, Nicolas; Role, André (1989). Bichat, la vie fulgurante d'un génie (in French). Paris: Perrin.

- Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic.