Bertel Thorvaldsen

Albert Bertel Thorvaldsen (Danish: [ˈpɛɐ̯tl̩ ˈtsʰɒːˌvælˀsn̩]; sometimes given as Thorwaldsen; 19 November 1770 – 24 March 1844) was a Danish and Icelandic sculptor and medalist of international fame,[1] who spent most of his life (1797–1838) in Italy. Thorvaldsen was born in Copenhagen into a working-class Danish/Icelandic family, and was accepted to the Royal Danish Academy of Art at the age of eleven. Working part-time with his father, who was a wood carver, Thorvaldsen won many honors and medals at the academy. He was awarded a stipend to travel to Rome and continue his education.

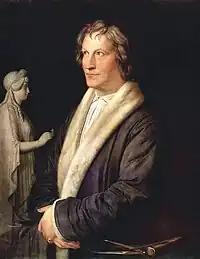

Bertel Thorvaldsen | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Carl Joseph Begas, c. 1820 | |

| Born | Albert Bertel Thorvaldsen 19 November 1770 Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Died | 24 March 1844 (aged 73) Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Known for | Sculpting |

In Rome, Thorvaldsen made a name for himself as a sculptor. Maintaining a large workshop in the city, he worked in a heroic neo-classicist style. His patrons resided all over Europe.[2]

Upon his return to Denmark in 1838, Thorvaldsen was received as a national hero. The Thorvaldsen Museum was erected to house his works next to Christiansborg Palace. Thorvaldsen is buried within the courtyard of the museum. In his time, he was seen as the successor of master sculptor Antonio Canova. Among his more famous public monuments are the statues of Nicolaus Copernicus and Józef Poniatowski in Warsaw; the statue of Maximilian I in Munich; and the tomb monument of Pope Pius VII, the only work by a non-Catholic in St. Peter's Basilica.

Early life and education

Thorvaldsen was born in Copenhagen in 1770 (according to some accounts, in 1768), the son of Gottskálk Þorvaldsson, an Icelander who had settled in Denmark. His father was a wood-carver at a ship yard, where he made decorative carvings for large ships and was the early source of influence on his son Bertel's development as a sculptor and on his choice of career. Thorvaldsen's mother was Karen Dagnes (her surname sometimes is reported as Grønlund), a Jutlandic peasant girl. His birth certificate and baptismal records have never been found, and the only existing record is of his confirmation in 1787.[3] Thorvaldsen had claimed descent from Snorri Thorfinnsson, the first European born in America.[4]

Thorvaldsen's childhood in Copenhagen was humble. His father had a drinking habit that slowed his career.[5] Nothing is known of Thorvaldsen's early schooling, and he may have been schooled entirely at home. He never became good at writing, and he never acquired much of the knowledge of fine culture that was expected from an artist.[6]

In 1781, by the help of some friends, eleven-year-old Thorvaldsen was admitted to Copenhagen's Royal Danish Academy of Art (Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi), first as a draftsman, and from 1786 at the modeling school. At night he would assist his father with wood carving. Among his professors were Nicolai Abildgaard and Johannes Wiedewelt, who are both likely influences for his later neo-classicist style.

At the Academy he was highly praised for his works. In 1793, he won several prizes, from silver to gold, for a relief of St. Peter healing a crippled beggar. He was consequently granted a Royal stipend, enabling him to complete his studies in Rome. Leaving Copenhagen on 30 August on the frigate Thetis, he landed in Palermo in January 1797 and traveled to Naples, where he studied for a month before making his entry to Rome on 8 March 1797. Since the date of his birth had never been recorded, he celebrated this day as his "Roman birthday" for the rest of his life.

Career

In Rome he lived at the Casa Buti, on the Via Sistina, in front of the Spanish Steps and had his workshop in the stables of the Palazzo Barberini. He was taken under the wing of Georg Zoëga a Danish archeologist and numismatist living in Rome. Zoëga took an interest in seeing to it that the young Thorvaldsen acquired an appreciation of the antique arts. As a frequent guest at Zoëga's house he met Anna Maria von Uhden, born Magnani. She had worked in Zoëga's house as a maid and had married a German archeologist. She became Thorvaldsen's mistress and left her husband in 1803. In 1813 she gave birth to a daughter, Elisa Thorvaldsen.

Thorvaldsen also studied with another Dane, Asmus Jacob Carstens whose handling of classic themes became a source of inspiration. Thorvaldsen's first success was the model for a statue of Jason; finished in 1801 it was highly praised by Antonio Canova, the most popular sculptor in the city. But the work was slow in selling and his stipend having run out, he planned his return to Denmark. In 1803, as he was set to leave Rome, he received the commission to execute the Jason in marble from Thomas Hope, a wealthy English art-patron. From that time Thorvaldsen's success was assured, and he did not leave Italy for sixteen years.

The marble Jason was not finished until 25 years later, as Thorvaldsen quickly became a busy man. Also in 1803, he started work on Achilles and Briseïs his first classically themed relief. In 1804 he finished Dance of the Muses at Helicon and a group statue of Cupid and Psyche and other important early works such as Apollo, Bacchus og Ganymedes. During 1805, he had to expand his workshop and enlist the help of several assistants. These assistants undertook most of the marble cutting, and the master limited himself to doing the sketches and finishing touches. Commissioned by Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1808 and finished in 1832 a statue of Adonis is one of the few works in marble carved solely by Thorvaldsen's own hand, and at the same time it is one of the works that is closest to the antique Greek ideals.

In the spring of 1818 Thorvaldsen fell ill, and during his convalescence he was nursed by the Scottish lady Miss Frances Mackenzie. Thorvaldsen proposed to her on 29 March 1819, but the engagement was cancelled after a month. Thorvaldsen had fallen in love with another woman: Fanny Caspers. Torn between Mackenzie and Anna Maria Von Uhden, the mother of his daughter Elisa Sophia Carlotta von Uhden Thorvaldsen, Thorvaldsen never succeeded in making Miss Caspers his wife.

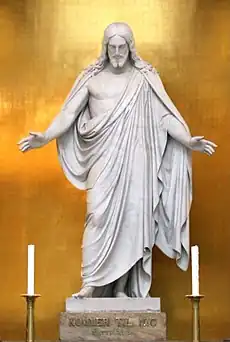

In 1819, he visited his native Denmark. Here he was commissioned to make the colossal series of statues of Christ and the Twelve Apostles for the rebuilding of Vor Frue Kirke (from 1922 known as the Copenhagen Cathedral) between 1817 and 1829, after its having been destroyed in the British bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807. These were executed after his return to Rome, and were not completed until 1838, when Thorvaldsen returned with his works to Denmark, being received as a hero.[7]

Death

Towards the end of 1843 he was prohibited from working for medical reasons, but he began to work again in January 1844. His last composition from 24 March was a sketch for a statue of the genie in chalk on a blackboard. At night he had dinner with his friends Adam Oehlenschläger and H. C. Andersen, and he is said to have referred to the finished museum saying: "Now I can die whenever it is time, because Bindesbøll has finished my tomb."

After the meal he went to the Copenhagen Royal Theatre where he died suddenly from a heart attack.[8] He had bequeathed a great part of his fortune for the building and endowment of a museum in Copenhagen, and left instructions to fill it with all his collection of works of art and the models for all his sculptures, a very large collection, exhibited to the greatest possible advantage. Thorvaldsen is buried in the courtyard of this museum, under a bed of roses, by his own wish.

Works

Thorvaldsen was an outstanding representative of the Neoclassical period in sculpture. In fact, his work was often compared to that of Antonio Canova and he became the foremost artist in the field after Canova's death in 1822. The poses and expressions of his figures are much more stiff and formal than those of Canova's. Thorvaldsen embodied the style of classical Greek art more than the Italian artist, he believed that only through the imitation of classical art pieces could one become a truly great artist.

Motifs for his works (reliefs, statues, and busts) were drawn mostly from Greek mythology, as well as works of classic art and literature. He created portraits of important personalities, as in his statue of Pope Pius VII. Thorvaldsen's statue of Pope Pius VII is found in the Clementine Chapel in the Vatican, for which he was the only non-Italian artist to ever have been commissioned to produce a piece. Because he was a Protestant and not a Catholic, the church did not allow him to sign his work. This led to the story of Thorvaldsen sculpting his own face on to the shoulders of the Pope, however any comparison between Thorvaldsen's portrait and the sculpture will show that this is just a fanciful story built on some smaller similarities.[9] His works can be seen in many European countries, especially in the Thorvaldsen Museum in Copenhagen, where his tomb is in the inner courtyard. Thorvaldsen's Lion Monument (1819) is in Lucerne, Switzerland. This monument commemorates the sacrifice of more than six hundred Swiss Guards who died defending the Tuileries during the French Revolution. The monument portrays a dying lion lying across broken symbols of the French monarchy.

Thorvaldsen produced some striking and affecting statues of historic figures, including two in Warsaw, Poland: an equestrian statue of Prince Józef Poniatowski that now stands before the Presidential Palace; and the seated Nicolaus Copernicus, before the Polish Academy of Sciences building—both located on Warsaw's Krakowskie Przedmieście. A replica of the Copernicus statue was cast in bronze and installed in 1973 on Chicago's lakefront along Solidarity Drive in the city's Museum Campus.[10] A statue (Gutenberg Denkmal) of Johannes Gutenberg by Thorvaldsen can be seen in Mainz, Germany.

Museums and collections

The Thorvaldsen Museum is the museum in Copenhagen, Denmark where Bertel Thorvaldsen's works are displayed. The museum is located on the small island of Slotsholmen in central Copenhagen next to Christiansborg Palace. Designed by Michael Gottlieb Bindesbøll, this building was constructed from public collection funds in 1837. The museum displays a collection of the artist's works in marble as well as plaster, including the original plaster models used in the making of cast bronze and marble statues and reliefs, copies of those works that are on display in museums, churches, and at other locations around the world.[11]

The museum also features Bertel Thorvaldsen's personal collection of paintings, Greek and Roman sculptures, drawings, and prints the artist collected during his lifetime, as well as personal belongings he used in his work and everyday life.

Outside Europe, Thorvaldsen is less well known.[12] However, in 1896 an American textbook writer wrote that his statue of the resurrected Christ, commonly referred to as Thorvaldsen's Christus (created for Vor Frue Kirke), was "considered the most perfect statue of Christ in the world."[7] The statue has appealed to the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and a 3.4 m replica is on display at Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Utah. There is also a replica of this statue in visitors' centers associated with the LDS Church's temples in Mesa, Arizona, Laie, Hawaii, México City, Los Angeles, California, Portland, Oregon, Washington D.C., Hamilton, New Zealand, and São Paulo, Brazil, along with visitors' centers in Independence, Missouri, and Nauvoo, Illinois. The Christus is also a feature of the visitors' center associated with the church's Rome Italy Temple, where it is displayed alongside Thorvaldsen's statues of the Twelve Apostles also from Vor Frue Kirke. In the Paris France Temple it is an outdoor feature, placed in the courtyard. Additionally, the LDS Church has historically used images of the statue in official church media, with this increasing with its use as a formal symbol, beginning in April 2020.[13]

Additional replicas of the Christus include a full-size replica at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland within its iconic dome,[14] and a full-sized copy in bronze at the Ben H. Powell III family plot in Oakwood Cemetery in Huntsville, Texas as a memorial to the Powell's son Rawley.

Thorvaldsen's Christus was recreated in Lego by parishioners of a Swedish Protestant church in Västerås and unveiled on Easter Sunday 2009.[15]

Thorvaldsen's primary mastery was his feel for the rhythm of lines and movements. Nearly all his sculptures can be viewed from any chosen angle without compromise of their impact. In addition, he had the ability to work in monumental size. Thorvaldsen's classicism was strict; nevertheless his contemporaries saw his art as the ideal, although afterwards art took new directions. A bronze copy of Thorvaldsen's Self-Portrait stands in Central Park, New York, near the East 97 Street entrance.

Gallery: Thorvaldsen's works

- Bertel Thorvaldsen's sculptures

Christus, Copenhagen Cathedral. Copies exist throughout the world.

Christus, Copenhagen Cathedral. Copies exist throughout the world._by_Thorvaldsen.jpg.webp) Christus draft (discolored by sculpting-room fireplace), Thorvaldsen Museum

Christus draft (discolored by sculpting-room fireplace), Thorvaldsen Museum Baptismal font, Copenhagen Cathedral

Baptismal font, Copenhagen Cathedral Jason with the Golden Fleece, Thorvaldsen's first masterpiece

Jason with the Golden Fleece, Thorvaldsen's first masterpiece Ganymede Waters Zeus as an Eagle, Thorvaldsen Museum

Ganymede Waters Zeus as an Eagle, Thorvaldsen Museum Venus with apple

Venus with apple Dancing Girl

Dancing Girl Tomb monument to Pope Pius VII, St. Peter's Basilica, Rome

Tomb monument to Pope Pius VII, St. Peter's Basilica, Rome Lion by Thorvaldsen.

Lion by Thorvaldsen.

Sir Walter Scott by Bertel Thorvaldsen

Sir Walter Scott by Bertel Thorvaldsen Possibly Lady Georgiana Bingham, carved c. 1821-1824, National Gallery of Art

Possibly Lady Georgiana Bingham, carved c. 1821-1824, National Gallery of Art

Notes

- Forrer, L. (1916). "Thorwaldsen, Albertus". Biographical Dictionary of Medallists. Vol. VI. London: Spink & Son Ltd. pp. 84–86.

- Alexander Sturgis. 2006. Rebels and Martyrs: The Image of the Artist in the Nineteenth Century, London: National Gallery (Great Britain), p. 52

- See the confirmation certificate at the Thorvaldsens Museum Archives

- Paul Henri Mallet, Thomas Percy, I. A. Blackwell, Sir Walter Scott, Northern Antiquities, Harvard University Press

- Just Mathias Thiele, Bertel Thorvaldsen, Mordaunt Roger Barnard. 1865. The Life of Thorvaldsen. Chapman and Hall pp. 3–4

- Just Mathias Thiele, Bertel Thorvaldsen, Mordaunt Roger Barnard. 1865. The Life of Thorvaldsen. Chapman and Hall p.8

- Coe, Fanny E. (1896). Dunton, Larkin (ed.). Modern Europe. The Young Folks' Library 9, The World and Its People 5. Boston: Silver Burdett. pp. 124–127. OCLC 14865981.

- Bencard, Ernst Jonas. "On the Cause of Thorvaldsen's Death". Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Richard P. McBrien: Lives of the Popes

- Graf, John, Chicago's Parks Arcadia Publishing, 2000, p. 13-14., ISBN 0-7385-0716-4.

- "Thorvaldsen collections". thorvaldsensmuseum.dk. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- (but see the important paper by Dimmick below).

- The Church's New Symbol Emphasizes the Centrality of the Savior, 4 April 2020

- Roylance, Lindsay (December 2003), "A Provacative Icon", Dome, Johns Hopkins Medicine, 54 (10): 1, archived from the original on 3 December 2013

- "Swedish parishioners unveil Jesus Lego statue", NBC News, Associated Press, 12 April 2009, archived from the original on 21 October 2013

Further reading

- Malta 1796–1797: Thorvaldsen's Visit (1996. Malta & Cop.)

- Jørnæs, B. Billedhuggeren Bertel Thorvaldsens liv og værk (1993)

- E. Lerberg, Fire danske Klassikere: Nicolai Abildgaard, Jens Juel, Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg og Bertel Thorvaldsen [exhibition catalogue] (1992)

- Kunstlerleben im Rom: Bertel Thorvaldsen, der danische Bildhauer und seine deutschen Freunde, ed. G. Bott [exhibition catalogue] (1991)

- Lauretta Dimmick, 'Mythic Proportion: Bertel Thorvaldsen's Influence in America', in Thorvaldsen: l'ambiente, l'influsso, il mito, ed. P. Kragelund and M. Nykjær (1991) (=Analecta Romana Instituti Danici, Supplementum 18.), pp. 169–191.

- The Age of Neoclassicism [exhibition catalogue] (1972)

- H. Fletcher, 'John Gibson: an English pupil of Thorvaldsen', in Apollo; 96:128 (1972 October), pp. 336–340.

- J. B. Hartmann, 'Canova, Thorvaldsen and Gibson', in English miscellany; 6 (1955), pp. 205–235.

- R. Zeitler, Klassizismus und Utopia: Interpretationen zu Werken von David, Canova, Carstens, Thorvaldsen, Koch (1954)

- Trier, S. Thorvaldsen (1903)

- Rosenberg, C. A. Thorwaldsen ... mit 146 Abbildungen (1896) (= Kunstlermonographie; 16)

- Wilde, A. Erindringer om Jerichau og Thorvaldsen (1884)

- Eugène Plon, Thorwaldsen, sa vie ... (1880)

- R. W. Buchanan, Thorvaldsen and his English critics (1865?)

- Thiele, J. M. Thorwaldsens Leben ... (1852–1856)

- Killerup, Thorwaldsens Arbeiten ... (1852)

- Andersen, B. Thorwaldsen (1845)

- Mordaunt Roger Barnard (trans) The life of Thorvaldsen: Collated from the Danish of Just Matthias Thiele, 1865 (Digitised )

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 882.

- Stefano Grandesso, Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1844), introduzione di Fernando Mazzocca, catalogo delle opere a cura di Laila Skjøthaug 2010, Cinisello Balsamo (MI), Silvana Editoriale, ISBN 978-88-366-1912-2.

- Stefano Grandesso, Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1844), Introduction by Fernando Mazzocca, Stig Miss; with catalogue by Laila Skjøthaug, Second English and Italian Edition, 2015, Cinisello Balsamo (Milan), Silvana Editoriale, ISBN 978-88-366-1912-2.

External links

- Thorvaldsen's Museum, Copenhagen

- Art and the empire city: New York, 1825–1861, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Thorvaldsen (see index)

- The Thorvaldsens Museum Archives, a Documentation Centre on the life, work and context of Bertel Thorvaldsen

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Adonis (links to larger image in new window)

- Adonis (5 views)

- Jason with the Golden Fleece (links to larger image)

- The Three Graces (relief)

- 23 works

- Albert Thorwaldsen 1770 – 1844, L'Illustration Journal Universel, No. 59 Vol III, April 1844 (French)

- Portrait by Samuel Morse, 1831