Battle of Peking (1900)

The Battle of Peking (Chinese: 北京之戰), or historically the Relief of Peking (Chinese: 北京解圍戰), was the battle fought on 14–15 August 1900 in Peking, in which the Eight-Nation Alliance relieved the siege of the Peking Legation Quarter during the Boxer Rebellion. From 20 June 1900, Boxers and Imperial Chinese Army troops had besieged foreign diplomats, citizens and soldiers within the legations of Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Britain, France, Italy, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, Russia, Spain and the United States.

| Battle of Peking | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Boxer Rebellion | |||||||

The Allied Armies launch a general offensive on Peking Castle, by Torajirō Kasai (1900) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Eight-Nation Alliance: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c.20,000 | c.20,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

60 killed 205 wounded | Heavy losses (Unknown total) | ||||||

Background

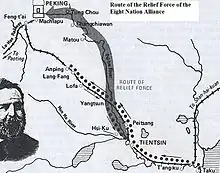

The first attempt to relieve the legations by a force of over 2,000 sailors and marines commanded by British Admiral Edward Seymour was turned back by strong opposition on 26 June.

On 4 August a second, much larger relief force, called the Eight-Nation Alliance, marched from Tientsien (Tianjin) toward Peking. The alliance force consisted of 22,000 troops from the following countries:

- Japan - 10,000

- Russia - 4,000 (infantry, Cossacks and artillery)

- Britain - 3,000 (mostly Indian infantry, cavalry and artillery)

- United States - 2,000 (soldiers and marines with artillery)

- France - 800 (Indochinese brigade with artillery)

- Germany - 200

- Austria - 100

- Italy - 100.[1]

Other sources give a figure of 18,000 troops.[2]

The Alliance forces defeated the Chinese army at the Battle of Beicang (Peitsang) on 5 August and the Battle of Yangcun (Yangtsun) on 6 August and reached Tongzhou (Tongchou), 14 miles from Peking, on 12 August.[3] The relief force was much reduced by heat exhaustion and sunstroke and the men available for the assault on Peking probably did not greatly exceed 10,000.[4]

The British, American and Japanese commanders wanted to push on and attack Peking on 13 August, but the Russian commander said he needed another day to prepare and 13 August was devoted to reconnaissance and rest.[5]

Objective

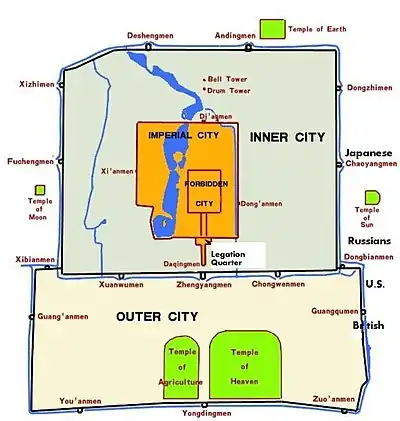

The objective of the alliance forces was to fight their way into the city of Peking, make their way to the Legation Quarter and rescue the 900 foreigners besieged there by the Chinese army since 20 June.

Peking had formidable defense works. The city was surrounded by walls 21 miles in length and broken by 16 gates. The wall around the Inner (Tartar) city was 40 feet tall and 40 feet wide at the top. The wall around the adjoining Outer (Chinese) city was 30 feet high. The population living within the walls was about one million people, although many had fled to escape the Boxers and the fighting between the Chinese army and the foreigners in the Legation Quarter.[6]

As the armies moved into position about five miles from the walls, on the night of 13 August, they could hear the sounds of heavy artillery and machine-gun fire from within the city. They feared they had arrived one day too late to rescue their countrymen.[7]

The relief force did not know that 2,800 destitute Chinese Christians had taken refuge in the Legation Quarter with the foreigners, nor did it know that three miles distant from the Legations a second siege was in progress. The Peitang (Beitang) cathedral of the Roman Catholic Church had been surrounded by Boxers and the Chinese army since 15 June. Defending the cathedral were 28 foreign priests and nuns, 43 French and Italian soldiers and 3,400 Chinese Catholics. The people sheltering in the Peitang had suffered several hundred killed, mostly from starvation, disease and mines detonated beneath the perimeter walls.[8] Sixty-six of the 900 foreigners in the Legation Quarter had been killed and 150 wounded during the siege. Casualties among the Chinese Christians were not recorded.[9]

Battle

The assault on Peking had taken on the character of a race to see which national army achieved the glory of relieving the Legations.[10]

The commanders of the four national armies agreed that each of them would assault a different gate. The Russians were assigned the most northerly gate, the Tung Chih (Dongzhi); the Japanese had the next gate south, the Chi Hua (Chaoyang); the Americans, the Tung Pein (Dongbien); and the British the most southern, the Sha Wo (Guangqui). The French apparently were left out of the planning.

The gate assigned to the Americans was nearest to the Legation Quarter and they seemed to have the best opportunity to reach the legations first. However, the Russians violated the plan, although it is uncertain whether it was intentional or not.[11] An advance Russian force arrived at the Americans' assigned gate, the Dongbien, about 3:00 a.m. on 14 August. They killed 30 Chinese outside the gate and blasted a hole in the door with artillery. Once inside the gate, however, in the courtyard between the inner and outer doors, they were caught in a murderous crossfire that killed 26 Russian soldiers and wounded 102. The survivors were pinned down for the next several hours.[12]

When the Americans arrived at their assigned gate that morning they found the Russians already engaged there and they moved their troops about 200 yards south. Once there, Trumpeter Calvin P. Titus volunteered to climb the 30-foot-tall wall, which he did successfully. Other Americans followed him, and at 11:03 a.m. the American flag was raised on the wall of the Outer city. American troops exchanged fire with Chinese forces on the wall and then climbed down the other side and headed west toward the Legation Quarter in the shadow of the wall of the Inner city.[13]

Meanwhile, the Japanese had encountered stiff resistance at their assigned gate and were subjecting it to an artillery barrage. The British had an easier time of it, approaching and passing through their gate, the Shawo or Guangqui, with virtually no opposition. Both Americans and British were aware that the easiest entry into the Legation Quarter was through the so-called Water Gate, a drainage canal running beneath the wall of the Inner city. The British got there first. They waded through the muck of the canal and into the Legation Quarter and were greeted by a cheering throng of the besieged, all decked out in their "Sunday best". The Chinese ringing the Legation Quarter fired a few shots, wounding a Belgian woman, and then fled. It was 2:30 p.m on 14 August. The British had not suffered a single casualty all day, except for one man who died of sunstroke.[14]

About 4:30 p.m., the Americans arrived in the Legation Quarter. Their casualties for the day were one killed and nine wounded, plus one badly injured in a fall while climbing the wall. Among the wounded was Smedley Butler who would later become a general and the most famous Marine of his era.[15] The Russian, Japanese and French forces entered Peking that evening as Chinese opposition melted away. The Siege of the Legations was over.[16]

Aftermath

The next morning, 15 August, Chinese forces – probably Dong Fuxiang's Gansu Muslim troops – still occupied parts of the wall of the Inner City and the Imperial and Forbidden Cities. Occasional shots were directed toward the foreign troops. General Chaffee, the American commander, ordered his troops to clear the wall and occupy the Imperial City. With assistance from the Russians and French, American artillery blasted its way through a series of walls and gates into the Imperial City, halting the advance at the gates of the Forbidden City. American casualties for the day were seven killed and 29 wounded.[17] One of those killed was Capt. Henry Joseph Reilly, 54 years old and born in Ireland, a renowned artilleryman.[18]

The Dowager Empress, Cixi, the emperor and several members of the court fled Peking in the early morning of 15 August, only a few hours before the Americans knocked up against the wall of the Forbidden City. She, dressed as a peasant woman, and the Imperial party slipped out of the city in three wooden carts. Chinese authorities called her flight to Shanxi province a "tour of inspection". Remaining in Peking to deal with the foreigners, and holed up in the Forbidden City, were trusted aides to the Dowager, including Ronglu, commander of the army and her friend since childhood.[19] At Zhengyang Gate the Muslim Kansu Braves engaged in a fierce battle against the Alliance forces. The commanding Muslim general in the Chinese army, General Ma Fulu, and four of his cousins were killed charging against the Alliance forces; meanwhile, a hundred Hui and Dongxiang Muslim troops from his home village died in the fighting at Zhengyang. The Battle at Zhengyang was fought against the British.[20] After the battle was over, the Kansu Muslim troops, including General Ma Fuxiang, were among those guarding the Empress Dowager during her flight.[21] The future Muslim General Ma Biao, who led Muslim cavalry to fight against the Japanese in the Second Sino-Japanese War, fought in the Boxer Rebellion under General Ma Haiyan as a private in the Battle of Peking against the foreigners. General Ma Haiyan died of exhaustion after the Imperial Court reached their destination, and his son Ma Qi took over his posts. Ma Fuxing also served under Ma Fulu to guard the Qing Imperial court during the fighting.[22] The Muslim troops were described as "the bravest of the brave, the most fanatical of fanatics : and that is why the defence of the Emperor's city had been entrusted to them."[23]

The relief of the siege at the Peitang did not take place until 16 August. Japanese troops stumbled across the Cathedral that morning but, without a common language, they and the besieged were both confused. Shortly, however, French troops arrived and marched into the cathedral to the cheers of the survivors.[24]

On 17 August, the representatives of the foreign powers met and recommended that "as the advance of the foreign troops into the Imperial and Forbidden Cities had been obstinately resisted by the Chinese troops", the foreign armies should continue to fight until "the Chinese armed resistance within the City of Peking and the surrounding country was crushed". They also declared "that in the crushing of the armed resistance lies the best and only hope of the restoration of peace".[25]

On 28 August, the foreign armies in Peking – swelled in numbers by the arrival of soldiers from Germany, Italy and Austria and additional troops from France – marched through the Forbidden City to demonstrate symbolically their complete control of Peking. Chinese authorities protested their entry. Foreigners and most Chinese were prohibited from setting foot in the Forbidden City. However, the Chinese gave way when the foreign armies promised not to occupy the Forbidden City but threatened to destroy it if their passage was disputed.[26]

Occupation

Peking was a battered city after the siege. The Boxers had begun the destruction, destroying all Christian churches and homes and starting fires that burned throughout the city. The Chinese artillery aimed at the Legation Quarter and Peitang during the siege had destroyed nearby neighborhoods. Unburied bodies littered the deserted streets.[27] The foreign armies divided Peking into districts. Each district was administered by one of the occupying armies.

The occupation of Peking became, in the words of an American journalist, "the biggest looting expedition since Pizarro".[28] Each nation accused the others of being most responsible for the looting. American missionary Luella Miner claimed that "The conduct of the Russian soldiers is atrocious, the French are not much better, and the Japanese are looting and burning without mercy".[29] Gaselee, noting the "unavoidable necessity" of looting, established a system whereby all loot was auctioned off at the British Legation every afternoon except Sunday, with the proceeds being distributed by a prize committee to the remaining British troops in the city.[30] Chaffee banned American soldiers from looting, although U.S. troops frequently violated that order to engage in pillaging around the city, which led an Army chaplain to complain that "Our rule against looting is totally ineffectual".[31]

The civilians and missionaries who had been besieged were some of the most prolific looters, as they were familiar with Peking. Some of the looting was justified as being done so for humanitarian reasons, such as the case of Catholic Bishop Pierre Favier and American Congregationalist William Scott Ament who had hundreds of starving Chinese Christians to care for and needed food and clothing. However, looting for necessities quickly became superseded by looting for profit, widely publicized by journalists—many indulged in looting on their own while condemning it when done by others.[32] Chinese citizens in Peking also indulged in looting and set up markets to sell the proceeds of their efforts.[33]

The Eight-Nation Alliance proceeded to dispatch punitive expeditions to the countryside to capture or kill suspected Boxers. During these expeditions, indiscriminate killings were frequently carried out by the soldiers. Chafee commented that "It is safe to say that where one real Boxer has been killed since the capture of Peking, fifty harmless coolies or laborers on the farms, including not a few women and children, have been slain".[34] The majority of the punitive expeditions were conducted by the French and Germans.[35]

A peace agreement was concluded between the Eight-Nation Alliance and representatives of the Chinese government Li Hung-chang and Prince Ching on 7 September 1901. The treaty required China to pay an indemnity of $335 million (over $4 billion in current dollars) plus interest over a period of 39 years. Also required was the execution or exile of government supporters of the Boxers and the destruction of Chinese forts and other defenses in much of northern China. Ten days after the treaty was signed the foreign armies left Peking, although legation guards would remain there until World War II.[36]

With the treaty signed the Empress Dowager Cixi returned to Peking from her "tour of inspection" on 7 January 1902 and the rule of the Qing dynasty over China was restored, albeit much weakened by the defeat it had suffered in the Boxer Rebellion and by the indemnity and stipulations of the peace treaty.[37] The Dowager died in 1908 and the dynasty imploded in 1911.

Legacy

In the Second Sino-Japanese War, when the Japanese asked the Muslim General Ma Hongkui to defect and become head of a Muslim puppet state under the Japanese, Ma responded through Zhou Baihuang, the Ningxia Secretary of the Nationalist Party to remind the Japanese military chief of staff Itagaki Seishiro that many of his relatives fought and died in battle against Eight Nation Alliance forces during the Battle of Peking, including his uncle Ma Fulu, and that Japanese troops made up the majority of the Alliance forces so there would be no cooperation with the Japanese.[38]

In popular culture

The events of the Battle of Peking are shown in the 1963 historical war film 55 Days at Peking by director Nicholas Ray.

Pictures

Gates crushed by Russian cannons during the night storming of Peking.

Gates crushed by Russian cannons during the night storming of Peking. The eastern wall, captured by Russian troops. A Russian flag can be seen on the tower above the gates.

The eastern wall, captured by Russian troops. A Russian flag can be seen on the tower above the gates. Defenders of the French Catholic church Beitang in Peking, August 1900, after a two-month siege.

Defenders of the French Catholic church Beitang in Peking, August 1900, after a two-month siege. Japanese infantry firing at the gates of Peking.

Japanese infantry firing at the gates of Peking.

See also

References

- War Department. Adjutant General’s Office. Report on Military Operations in South Africa and China, Vol. XXXIII, Washington: Gov Printing Office, July 1901, pp. 568-571

- Thompson, Larry Clinton (2009). William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris, and the Ideal Missionary. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 163–165. Different sources give slightly different numbers.

- Fleming, Peter (1959). The Siege at Peking: The Boxer Rebellion New York: Dorset Press. pp. 184–189.

- Thompson, p. 172

- Daggett, Brig. Gen. A. S. (1903). America in the China Relief Expedition. Kansas City: Hudon-Kimberly Publishing Co. p. 75.

- Thompson, pp. 33–34

- Daggett, p. 77

- Thompson, pp. 115–117

- Fleming, p. 211

- Fleming, p. 200

- Fleming, pp. 201–203

- Savage Landor, A. Henry (1901). China and the Allies. 2 Vols. New York: William Heinemann. Vol II. p. 175.

- Daggett, pp. 81–82

- Fleming, pp. 203–208

- Thompson, pp. 178–181

- Fleming, pp. 209–210

- Daggett, pp. 95–104

- "Arlingtoncemetery.net". www.arlingtoncemetery.net. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- Fleming, pp. 232–239. Ronglu later joined the Dowager on her tour of inspection.

- Michael Dillon (16 December 2013). China's Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. Routledge. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-1-136-80933-0.

- Lipman, Jonathan Newaman (2004). Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-295-97644-6. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Garnaut, Anthony. "From Yunnan to Xinjiang:Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals" (PDF). Australian National University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- Arnold Henry Savage Landor (1901). China and the Allies. Charles Scribner's sons. pp. 194–.

lotus catholics victims allies.

- Thompson, p. 189

- "1900 CM MacDonald - the Old China Hands Project". Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- Daggett, pp. 106–108

- Daggett, p. 111; Smith, Arthur H. (1901). China in Convulsion. 2 Vols. New York: F. H. Revell Co. Vol II, pp. 519–520.

- Lynch, George (1901). The War of the Civilizations. New York: Longmans, Green & Co. p. 179.

- Preston, Diana (1999). The Boxer Rebellion. New York: Berkley Books. p. 284.

- "Boxers: Looting" citing A. A. S Barnes, On Active Service With the Chinese Regiment : A Record of the Operations of the First Chinese Regiment in North China From March to October 1902 ed. rev. & enl ed., (London: Grant Richards, 1902), p139

- Thompson, 194–196

- Thompson, pp. 194–199, 205

- Chamberlin, Wilbur J. (1903). Ordered to China. New York: F. A. Stokes Co., pp. 83–84. Chamberlin was the journalist who accused William Scott Ament of looting, thus igniting the Twain-Ament Indemnities Controversy.

- Lynch, George (1901). The War of the Civilizations. London: Longmans, Green. p. 84.

- Thompson, pp. 198–199, 204

- Preston, pp. 310–311

- Preston, pp. 312–315

- LEI, Wan (February 2010). "The Chinese Islamic "Goodwill Mission to the Middle East" During the Anti-Japanese War". DÎVÂN DİSİPLİNLERARASI ÇALIŞMALAR DERGİSİ. cilt 15 (sayı 29): 133–170. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

Further reading

- Д.Г.Янчевецкий "У стен недвижного Китая". Санкт-Петербург - Порт-Артур, 1903 (D.G.Yanchevetskiy "Near the Walls of Unmoving China", Sankt-Peterburg - Port-Artur, 1903)

- Fleming, Peter (1959). The Siege of Peking. London: Hart-Davis.

- Giles, Lencelot (1970). The Siege of the Peking Legations; A Diary. Edited with introduction, Chinese anti-foreignism and the Boxer uprising, by L. R. Marchant. Nedlands, W.A.: University of Western Australia Press.

- В. Г. Дацышен «Русско-китайская война 1900 года. Поход на Пекин» – СПБ, 1999. ISBN 5-8172-0011-2 (V.G. Datsishen "Russo-Chinese war of 1900. March to Beijing", Sankt-Peterburg, 1999)

- Harrington, Peter (2001). Peking 1900. The Boxer Rebellion. Oxford: Osprey.

- Preston, Diana (1999). The Boxer Rebellion: The Dramatic Story of China's War on Foreigners That Shook the World in the Summer of 1900. New York: Walker and Co.

- Thompson, Larry Clinton (2009). William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris, and the Ideal Missionary. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris and the "Ideal Missionary"

- China's Tragic Years (2001). China's Tragic Years, 1900–1901, Through a Foreign Lens.

External links

Media related to Battle of Peking at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Peking at Wikimedia Commons