Aftershock

In seismology, an aftershock is a smaller earthquake that follows a larger earthquake, in the same area of the main shock, caused as the displaced crust adjusts to the effects of the main shock. Large earthquakes can have hundreds to thousands of instrumentally detectable aftershocks, which steadily decrease in magnitude and frequency according to a consistent pattern. In some earthquakes the main rupture happens in two or more steps, resulting in multiple main shocks. These are known as doublet earthquakes, and in general can be distinguished from aftershocks in having similar magnitudes and nearly identical seismic waveforms.

| Part of a series on |

| Earthquakes |

|---|

|

|

Distribution of aftershocks

Most aftershocks are located over the full area of fault rupture and either occur along the fault plane itself or along other faults within the volume affected by the strain associated with the main shock. Typically, aftershocks are found up to a distance equal to the rupture length away from the fault plane.

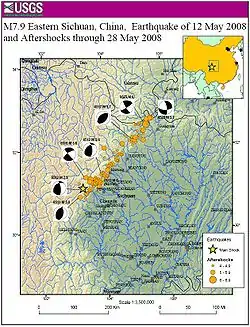

The pattern of aftershocks helps confirm the size of area that slipped during the main shock. In the case of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and the 2008 Sichuan earthquake the aftershock distribution shows in both cases that the epicenter (where the rupture initiated) lies to one end of the final area of slip, implying strongly asymmetric rupture propagation.

Aftershock size and frequency with time

Aftershocks rates and magnitudes follow several well-established empirical laws.

Omori's law

The frequency of aftershocks decreases roughly with the reciprocal of time after the main shock. This empirical relation was first described by Fusakichi Omori in 1894 and is known as Omori's law.[1] It is expressed as

where k and c are constants, which vary between earthquake sequences. A modified version of Omori's law, now commonly used, was proposed by Utsu in 1961.[2][3]

where p is a third constant which modifies the decay rate and typically falls in the range 0.7–1.5.

According to these equations, the rate of aftershocks decreases quickly with time. The rate of aftershocks is proportional to the inverse of time since the mainshock and this relationship can be used to estimate the probability of future aftershock occurrence.[4] Thus whatever the probability of an aftershock are on the first day, the second day will have 1/2 the probability of the first day and the tenth day will have approximately 1/10 the probability of the first day (when p is equal to 1). These patterns describe only the statistical behavior of aftershocks; the actual times, numbers and locations of the aftershocks are stochastic, while tending to follow these patterns. As this is an empirical law, values of the parameters are obtained by fitting to data after a mainshock has occurred, and they imply no specific physical mechanism in any given case.

The Utsu-Omori law has also been obtained theoretically, as the solution of a differential equation describing the evolution of the aftershock activity,[5] where the interpretation of the evolution equation is based on the idea of deactivation of the faults in the vicinity of the main shock of the earthquake. Also, previously Utsu-Omori law was obtained from a nucleation process.[6] Results show that the spatial and temporal distribution of aftershocks is separable into a dependence on space and a dependence on time. And more recently, through the application of a fractional solution of the reactive differential equation,[7] a double power law model shows the number density decay in several possible ways, among which is a particular case the Utsu-Omori Law.

Båth's law

The other main law describing aftershocks is known as Båth's Law[8][9] and this states that the difference in magnitude between a main shock and its largest aftershock is approximately constant, independent of the main shock magnitude, typically 1.1–1.2 on the Moment magnitude scale.

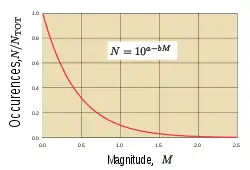

Gutenberg–Richter law

.svg.png.webp)

Aftershock sequences also typically follow the Gutenberg–Richter law of size scaling, which refers to the relationship between the magnitude and total number of earthquakes in a region in a given time period.

Where:

- is the number of events greater or equal to

- is magnitude

- and are constants

In summary, there are more small aftershocks and fewer large aftershocks.

Effect of aftershocks

Aftershocks are dangerous because they are usually unpredictable, can be of a large magnitude, and can collapse buildings that are damaged from the main shock. Bigger earthquakes have more and larger aftershocks and the sequences can last for years or even longer especially when a large event occurs in a seismically quiet area; see, for example, the New Madrid Seismic Zone, where events still follow Omori's law from the main shocks of 1811–1812. An aftershock sequence is deemed to have ended when the rate of seismicity drops back to a background level; i.e., no further decay in the number of events with time can be detected.

Land movement around the New Madrid is reported to be no more than 0.2 mm (0.0079 in) a year,[10] in contrast to the San Andreas Fault which averages up to 37 mm (1.5 in) a year across California.[11] Aftershocks on the San Andreas are now believed to top out at 10 years while earthquakes in New Madrid were considered aftershocks nearly 200 years after the 1812 New Madrid earthquake.[12]

Foreshocks

Some scientists have tried to use foreshocks to help predict upcoming earthquakes, having one of their few successes with the 1975 Haicheng earthquake in China. On the East Pacific Rise however, transform faults show quite predictable foreshock behaviour before the main seismic event. Reviews of data of past events and their foreshocks showed that they have a low number of aftershocks and high foreshock rates compared to continental strike-slip faults.[13]

Modeling

Seismologists use tools such as the Epidemic-Type Aftershock Sequence model (ETAS) to study cascading aftershocks and foreshocks.[14] [15]

Psychology

Following a large earthquake and aftershocks, many people have reported feeling "phantom earthquakes" when in fact no earthquake was taking place. This condition, known as "earthquake sickness" is thought to be related to motion sickness, and usually goes away as seismic activity tails off.[16][17]

References

- Omori, F. (1894). "On the aftershocks of earthquakes" (PDF). Journal of the College of Science, Imperial University of Tokyo. 7: 111–200. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- Utsu, T. (1961). "A statistical study of the occurrence of aftershocks". Geophysical Magazine. 30: 521–605.

- Utsu, T.; Ogata, Y.; Matsu'ura, R.S. (1995). "The centenary of the Omori formula for a decay law of aftershock activity". Journal of Physics of the Earth. 43: 1–33. doi:10.4294/jpe1952.43.1.

- Quigley, M. "New Science update on 2011 Christchurch Earthquake for press and public: Seismic fearmongering or time to jump ship". Christchurch Earthquake Journal. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Guglielmi, A.V. (2016). "Interpretation of the Omori law". Izvestiya, Physics of the Solid Earth. 52 (5): 785–786. arXiv:1604.07017. Bibcode:2016IzPSE..52..785G. doi:10.1134/S1069351316050165. S2CID 119256791.

- Shaw, Bruce (1993). "Generalized Omori law for aftershocks and foreshocks from a simple dynamics". Geophysical Research Letters. 20 (10): 907–910. Bibcode:1993GeoRL..20..907S. doi:10.1029/93GL01058.

- Sánchez, Ewin; Vega, Pedro (2018). "Modelling temporal decay of aftershocks by a solution of the fractional reactive equation". Applied Mathematics and Computation. 340: 24–49. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2018.08.022. S2CID 52813333.

- Richter, Charles F., Elementary seismology (San Francisco, California, USA: W. H. Freeman & Co., 1958), page 69.

- Båth, Markus (1965). "Lateral inhomogeneities in the upper mantle". Tectonophysics. 2 (6): 483–514. Bibcode:1965Tectp...2..483B. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(65)90003-X.

- Elizabeth K. Gardner (2009-03-13). "New Madrid fault system may be shutting down". physorg.com. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- Wallace, Robert E. "Present-Day Crustal Movements and the Mechanics of Cyclic Deformation". The San Andreas Fault System, California. Archived from the original on 2006-12-16. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- "Earthquakes Actually Aftershocks Of 19th Century Quakes; Repercussions Of 1811 And 1812 New Madrid Quakes Continue To Be Felt". Science Daily. Archived from the original on 8 November 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- McGuire JJ, Boettcher MS, Jordan TH (2005). "Foreshock sequences and short-term earthquake predictability on East Pacific Rise transform faults". Nature. 434 (7032): 445–7. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..457M. doi:10.1038/nature03377. PMID 15791246. S2CID 4337369.

-

For example: Helmstetter, Agnès; Sornette, Didier (October 2003). "Predictability in the Epidemic-Type Aftershock Sequence model of interacting triggered seismicity". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 108 (B10): 2482ff. arXiv:cond-mat/0208597. Bibcode:2003JGRB..108.2482H. doi:10.1029/2003JB002485. S2CID 14327777.

As part of an effort to develop a systematic methodology for earthquake forecasting, we use a simple model of seismicity based on interacting events which may trigger a cascade of earthquakes, known as the Epidemic-Type Aftershock Sequence model (ETAS).

- For example: Petrillo, Giuseppe; Lippiello, Eugenio (December 2020). "Testing of the foreshock hypothesis within an epidemic like description of seismicity". Geophysical Journal International. 225 (2): 1236–1257. doi:10.1093/gji/ggaa611. ISSN 0956-540X.

- "Japanese researchers diagnose hundreds of cases of 'earthquake sickness'". The Daily Telegraph. 20 June 2016.

- "After the earthquake: why the brain gives phantom quakes". The Guardian. 6 November 2016.

External links

- Earthquake Aftershocks Not What They Seemed at Live Science