Vasili III of Russia

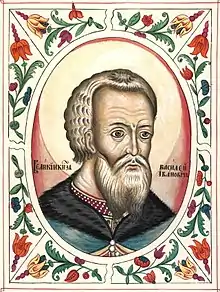

Vasili III Ivanovich (Russian: Василий III Иванович; 25 March 1479 – 3 December 1533) was Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1505 until his death in 1533.[1][2] He was the son of Ivan III and Sophia Paleologue and was christened with the name Gavriil (Гавриил). He had three brothers: Yuri (born in 1480), Simeon (born in 1487) and Andrei (born in 1490), as well as five sisters: Elena (born and died in 1474), Feodosiya (born and died in 1475), another Elena (born 1476), another Feodosiya (born 1485) and Eudoxia (born 1492).[3]

| Vasili III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sovereign of all Russia | |||||

Engraving by André Thevet, 1584 | |||||

| Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia | |||||

| Reign | 6 November 1505 – 3 December 1533 | ||||

| Coronation | 14 April 1502 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ivan III | ||||

| Successor | Ivan IV | ||||

| Born | 25 March 1479 Moscow, Grand Principality of Moscow | ||||

| Died | 3 December 1533 (aged 54) Moscow, Grand Principality of Moscow | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouses | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Rurik | ||||

| Father | Ivan III of Russia | ||||

| Mother | Sophia Paleologue | ||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox | ||||

Foreign affairs

Vasili III continued the policies of his father Ivan III and spent most of his reign consolidating Ivan's gains. Vasili annexed the last surviving autonomous provinces: Pskov in 1510, appanage of Volokolamsk in 1513, principalities of Ryazan in 1521 and Novgorod-Seversky in 1522.

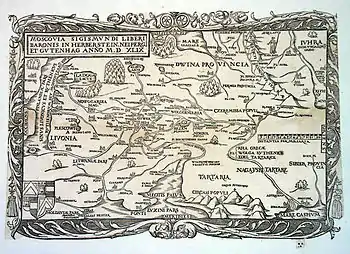

Vasili also took advantage of the difficult position of Sigismund of Poland to capture Smolensk, the great eastern fortress of Lithuania (siege started 1512, ended in 1514), chiefly through the aid of the rebel Lithuanian, Prince Mikhail Glinski, who provided him with artillery and engineers. The loss of Smolensk was an important injury inflicted by Russia on Lithuania in the course of the Russo-Lithuanian Wars and only the exigencies of Sigismund compelled him to acquiesce in its surrender (1522).[4]

In 1521 Vasili received an emissary of the neighboring Iranian Safavid Empire, sent by Shah Ismail I whose ambitions were to construct an Irano-Russian alliance against the common enemy, the Ottoman Empire.[5]

Vasili was equally successful against the Crimean Khanate. Although in 1519 he was obliged to buy off the Crimean khan, Mehmed I Giray, under the very walls of Moscow, towards the end of his reign he established Russian influence on the Volga. In 1531–32 he placed the pretender Cangali khan on the throne of Khanate of Kazan.[4]

Vasili was the first grand-duke of Moscow who adopted the title of tsar and the double-headed eagle of the Byzantine Empire.[4]

Domestic affairs

Regarding internal policy, Vasili III enjoyed the support of the Church in his struggle with the feudal opposition. In 1521, metropolitan Varlaam was banished for refusing to participate in Vasili's fight against an appanage prince, Vasili Ivanovich Shemyachich. Rurikid princes Vasili Shuisky and Ivan Vorotynsky were also sent into exile. The diplomat and statesman, Ivan Bersen-Beklemishev, was executed in 1525 for criticizing Vasili's policies. Maximus the Greek (publicist), Vassian Patrikeyev (statesman) and others were sentenced for the same reason in 1525 and 1531. During the reign of Vasili III, the landownership of the gentry increased, while authorities actively tried to limit immunities and privileges of boyars and the nobility.

Family life

.jpg.webp)

By 1526 when he was 47 years old, Vasili had been married to Solomonia Saburova for over 20 years with no heir to his throne being produced. Conscious of her husband's disappointment, Solomonia tried to remedy this by consulting sorcerers and going on pilgrimages. When this proved unsuccessful, Vasili consulted the boyars, announcing that he did not trust his two brothers to handle Russia's affairs.

The boyars suggested that he take a new wife, and despite much opposition from the clergy, he divorced his barren wife and married Princess Elena Glinskaya, the daughter of a Serbian princess and niece of his friend Michael Glinski. Not many of the boyars approved of his choice, as Elena was of Catholic upbringing. Vasili was so smitten that he defied Russian social norms and trimmed his beard to appear younger. After three days of matrimonial festivity, the couple consummated their marriage, though initially it appeared that Elena was as sterile as Solomonia. The Russian populace began to suspect this was a sign of God's disapproval of the marriage. However, to the great joy of Vasili and the populace, the new tsaritsa gave birth to a son, who would succeed him as Ivan IV. Three years later, a second son, Yuri, was born.[3] According to a story, Solomonia Saburova also bore a son in the convent where she had been confined, just several months after the controversial divorce.

Death

Whilst out hunting on horseback near Volokolamsk, Vasili felt a great pain in his right hip, the result of an abscess. He was transported to the village of Kolp, where he was visited by two German doctors who were unable to stop the infection with conventional remedies. Believing that his time was short, Vasili requested to be returned to Moscow, where he was kept in the Saint Joseph Cathedral along the way. By 25 November 1533, Vasili reached Moscow and asked to be made a monk before dying. Taking on the name Varlaam, Vasili died at midnight, 3 December 1533.[3]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Vasili III of Russia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vasili III in culture

Vasili was the subject of the opera Neprigozhaya by composer Ella Adayevskaya

References

- Filjushkin, Alexander (2008). Ivan the Terrible : a military history. London. ISBN 9781848325043.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - MacKenzie, David (2002). A history of Russia, the Soviet Union, and beyond (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. p. 115. ISBN 9780534586980.

- Troyat, Henri (1993). Ivan le terrible (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-064473-4.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). "Basil s.v. Basil III.". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 468–469.

- Relations between Tehran and Moscow, 1979–2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)