Baseball cheering culture in South Korea

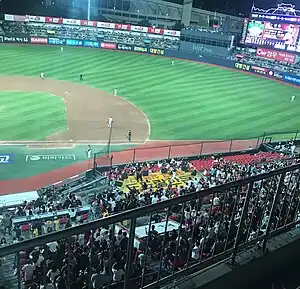

The baseball cheering culture in South Korea started in the 1990s and continues to the present.[1] There are 10 professional clubs and each club has its own way of cheering.[2] The Korean cheering culture generally shares similar characteristics: collective, enthusiastic and empathetic. Baseball cheering is popular because of easy-to-learn fight songs, break-time events and a variety of foods. Baseball cheering is performed in most parts of a ballpark.[3][4][5]

Cheering methods

Fight songs

Korean baseball fight songs consist of the song for each club and songs for individual players.[3][5] The fight song is a key element of Korea's baseball cheering culture. Cheering is done for the offence. Each batter has a personal fight song, sung when the batter enters the batter's box. The melodies of fight songs are taken from famous pop songs or K-pop songs, with lyrics rewritten to make it easy for the crowd to sing along. There are cell phone mobile applications that allow baseball fans to listen to the fight songs of clubs and players in advance.[6]

Cheering tools

In the early days of Korea's professional baseball league, which was started in 1982, the most commonly used cheering tools were Korean traditional musical instruments, such as Buk, Jing, and Kkwaenggwari. But nowadays, a typical example of a cheering tool is cylindrical, inflatable balloon sticks, now commonly known in the English-speaking world as thundersticks. They are used for cheering by beating a pair of balloon sticks together to make a loud sound.[7][3] The first club in the world to introduce balloon sticks was the LG Twins.[7][8] In the early 1990s they made balloon sticks out of polyethylene. It has been evolving and now it is recyclable, as the sticks can be inflated for use then deflated for storage until the next game.[7][5]

Each club has its own color for the balloon sticks: SK Wyverns is red, Samsung Lions is blue, Doosan Bears is white, Kia Tigers is yellow, LG Twins is red, Nexen Heroes is pink and Hanwha Eagles is orange.[9]

Another interesting characteristic of Korean baseball cheering is fans wearing team uniform shirts with players' names.[5] They wear this to feel a sense of belonging, solidarity and pride. Symbolic accessories and cheering tools play a similar role. There are stores in each stadium, so it is easy for supporters to buy cheer-related items.[10]

Cheer leaders

The Korea Baseball Organization did not have standardized cheering methods until the 1990s. It was the audiences who became the initiators of cheering. The initial ways of cheering were clapping and spontaneous singing. But in time, official cheer leaders appeared.[11] Cheer leaders and cheer leading captain are the ones who take the lead. Each club has one captain and four or five cheer leaders. Cheer leaders dance to the chant the captain is making. Basically, they start cheering with the club's fight songs, but sometimes they lead the cheering using the latest K-pop songs.[11][5]

Cheering features of each stadium

Foods

Each stadium has specialty food associated with cheering. A typical example of baseball stadium food is "Chimaek," which is fried chicken and beer.[12] There are various kinds of cheering foods featured at each ballpark. These are often the representative foods of the region where the ballpark is located. In Daegu Samsung Lions Park, there are Napjak Mandu (flat grilled dumplings),[13] Samgyeopsal (Korean-style bacon) and kebab.[14] In Busan Sajik Stadium, Buljokbal (spicy Jokbal), Bulgopchang (spicy Gopchang)[15] and fast foods such as hamburgers and fried chicken. In Seoul Jamsil Stadium, Jokbal (pig's trotters), in Gwangju Kia Champions Field, Garak Guksu (boiled thin noodles in dried anchovy broth),[16] in Hanwha Life Insurance Eagles Park, in Jinmi Tongdak and in Suwon KT Wiz Park, chicken.[15][5]

Cheering zones

Each baseball stadium has its sections of unique themed seats.[17][18][3] Incheon Munhak Baseball Stadium has a "T Green Zone", "Happiness Zone", "Skybox Zone", and "Barbecue Zone." "T Green Zone" is located on the grassy hillside which is available to set up a tent or lay a mat. This zone is recommended to family audiences because it is not too crowded and there is a kid's park near by. "Happiness Zone" is located at the backstop and the seats are equipped with tables. "Barbecue Zone" can accommodate up to 200 people at once. It is Korea's first stadium to provide fans a way to cook meat while watching baseball. At the store inside the stadium they sell meat and lend grills. "Skybox Zone" is located indoors, so watching baseball game isn't restricted by bad weather. Lastly, there is a "Homerun Couple Zone" in the outfield bleachers. Many couples enjoy dating there.[19]

Jamsil stadium's "Exciting Zone" allows fans to see players close up, but as this zone is close to the playing field, audiences have to be cautious about safety and borrow a helmet.[20]

Suwon KT Wiz park has a "Hite Pub" and "Playstation Lounge." "Hite Pub" is Korea's first sports pub and the cost of one glass of beer and food is included in the ticket price. In the "Playstation Lounge" audiences can enjoy the match in the assigned room in which a PlayStation is equipped.[21]

Daejeon Hanwha Life Insurance Eagles Park has an "Outfield Lawn Seat" and "Outfield Fieldbox." At the "Outfield Lawn Seat", audiences can enjoy the game with the feeling of a picnic. The "Outfield Fieldbox" is where audiences can watch the game from seats inside the box.[22] Busan Sajik Stadium has a "Rocket Battery Zone." There, people can enjoy the baseball game and camping at the same time, so it is recommended to family fans. These two stadiums both have an "Exciting Zone." This zone is close to the ground so audiences can enjoy the players’ dynamic game. It can be interesting to watch the game at ground eye level, but as many foul balls fly toward the seats, children are not allowed to enter as it could be somewhat dangerous.[23]

"Tigers Family Seat" is most famous at Gwangju Kia Champions Field. There are seats and tables for four to six people, so audiences can watch the game comfortably.[24] Masan Sports Complex Baseball Stadium has the "Dinos Mattress Seat." Audiences can watch the game lying on comfortable mattresses. They can borrow a parasol and beach towel.[25] And there is a unique stand made up of wooden decks. It is for family audiences and can accommodate six people. Audiences can party there, and no one complains about making noise.[26]

Cheering cultures of each club

The clubs of the Korean professional baseball league each have a unique cheering culture.[27] Fans of the Lotte Giants use newspapers and orange plastic bags as cheering tools.[28] Newspapers are rolled up and swayed in the air. People wear plastic bags on their heads, some knotted to look like Mickey Mouse ears. The plastic bags were initially intended to handle garbage, but the supporters started to use them as a cheering tool. The Lotte Giants also have unique chants, such as 'Azura' and 'Ma'. 'Azura' is a dialect word, implying 'yield a foul ball/home run ball to children', and 'Ma' is a dialect for calling children, implying 'throw the ball forward' (used when the pitcher throws to first base to check a runner). In response to 'Ma', supporters of other clubs make a counter-chant such as 'Wa' (a dialect of 'why').[29][3][5]

Hanwha Eagles went through a decline of organized cheering starting in 2009. This led many baseball fans to start cheering for visiting teams. The Hanwha Eagles are trying to figure out how to keep track of the new trends and revitalize their fan base. They started to use Fanbots, a cheering robot made as part of the social cheering campaign for fans who want to support the team but cannot attend the games in person. Anytime, anywhere, if people upload a cheering message via web or mobile, the message is sent to a Fanbot in real time and to be displayed on the board Fanbot is holding. The Hanwha Eagles are the first club to use Fanbots.[30][3]

The biggest feature of the Doosan Bears is that there are many fans who go cheering at away games. In addition, the percentage of female audience members is high. In the 2015 season, the percentage of female audiences was 43 percent for all teams, while for the Doosan Bears, it was 53 percent. For this reason, Doosan Bears is the only team in the league to have separate parts for the male and female in cheering songs.[31]

The KIA Tigers have their base in Gwangju, so they have many fans in Jeolla-do. They support the team regardless of their performance. The LG fans are similar in this regard. The official Kia Tigers team color is red but they use yellow balloon sticks for cheering. Some fans call the yellow balloon sticks a 'pickled radish'.[32]

Globalization

Korea's baseball cheering culture has been observed to be spreading to other nations.[33] The fight song for Eric Thames is one example.[34] Thames, who had been a member of Korea's Changwon NC Dinos (2014–2016), returned to U.S. Major League Baseball with the Milwaukee Brewers in 2017. His Korean theme song was played when he came to bat for Milwaukee. The song resounded through the Milwaukee stadium. His teammates, who did not know about the idea of personal fight songs, showed interest and hummed its melody.[35][36]

Challenges

Crisis

Recently the issue of copyright for club chants or fight songs has emerged.[37] Clubs want to make their song legitimate and are negotiating with the original copyright holders to use the fight songs familiar to the fans, but as the legal wrangling is ongoing, the clubs have either made some changes to the songs or used the songs without license to do so. The copyright owners for the original songs have prepared class action lawsuits.[38]

Traditionally, the fight songs of each club were created without thought to the original copyright holder. The song would be altered by changing the lyrics, but this violates the author's intellectual property. South Korean copyright law largely protects both the author's property rights and moral rights. Property rights refer to the rights to the media that is owned by the creators. Usually, content producers are paid for allowing others to use their creation. Moral rights in South Korea are related to the issue of the creator's psychological profit. This includes the right to maintain the identity of the content. This means that anyone using the author's creation must not change its original form. However, the clubs usually modify the original lyrics or tune. Therefore, even though the clubs often pay a large sum for the author's property rights, the fight songs violate the author's moral rights.[39]

Criticism

Korea's baseball cheering culture is largely considered to be positive, but some issues have arisen over the course of its development. First is the "Azura Culture", the cheering culture of the Lotte Giants. This culture is semi-coercive rather than voluntary. Initially, this culture began with the expectation that if adult spectators pass a foul or home run ball to a child, the conflicts between the adults to get the ball might decrease. This culture also has the purpose of presenting a child with a good memory of watching a baseball game.[40]

However, in the coercive atmosphere, there are a few audiences with bad manners who take the ball away from the teenagers. As a result, there is a growing criticism about whether "Azura Culture" is truly a good one. There is an ongoing debate online. Some even refer to "Azura Culture" as "robbery in the baseball stadium". As people give the ball to the child before shouting "Azura", the excitement of shouting it is decreasing.[41]

Recently, other criticisms have been raised. Boisterous cheering culture makes watching the baseball game more joyful, but for some people who want to watch the game quietly, it is annoying. Residents neighboring the ballpark also suffer from the noise. Residents living in the apartment near Kia Champions Field Ball Park sued Gwangju city and the Kia Tigers club.[42] As Korea's ballparks are located near very populated regions, it seems to be necessary to resolve the conflict between local residents and the baseball field.[43]

References

- "한국 야구 응원 문화". blog.naver.com (in Korean). 2016-07-31. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- 허, 남설 (2015-03-29). "한국 야구 팬들의 열정 넘치는 응원 현장". The Kyunghyang Shinmun (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- Sang-Hun, Choe (2014-11-02). "In Korean Baseball, Louder Cheers and More Squid". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- "즐거운 소란, 프로야구 응원 재개 - 한국의 스포츠 응원문화". blog.naver.com (in Korean). 2014-06-16. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "A look inside South Korean baseball's elaborate 'cheer culture'". ABC News. 2017-11-01. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- 이, 대호 (2016-07-16). "보크는 몰라도, 응원가는 술술 나와요". Yonhap News (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- 이, 길상 (2009-09-23). "전태수 사장이 밝히는 막대풍선의 역사". dongA.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- Engber, Daniel (13 June 2014). "Who Made That Inflatable Noisemaker?". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- Pg 71 - Korean Culture and Information Service; Won Hee-bok (2012). K-SPORTS A New Breed of Rising Champions. Korea.net. ISBN 9788973755653. - Total pages: 108

- "MD 상품과 e스포츠 응원 문화". Daily e-sports (in Korean). 2017-08-18. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "막대풍선 들고 "와와"... 프로야구 응원, 좀 바꿉시다". 오마이스타. 2017-03-16. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "야구장서 치맥파티... 하루 1000마리 날개 돋친 듯". 한국일보 (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "야구장 엔터테인먼트는 '춘추전국시대'". 중앙시사매거진. 2017-10-23. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "[이슈가 Money?] 치어리더 쟁탈전..지정석 1만원". 2011-04-10. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "힐만 버거ㆍ민우 바나나… 난 요거 먹으러 야구장 간다". 한국일보 (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "'야구 초보' 당신을 위한 2012 프로야구 친절 설명서". Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ""이왕이면 명당자리"…프로야구 구장별 베스트 명당". 종합일간지 : 신문/웹/모바일 등 멀티 채널로 국내외 실시간 뉴스와 수준 높은 정보를 제공 (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "(주)신한우리경매 맙소사같은 인생 : 네이버 블로그". blog.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- 엠스플뉴스. "<이동섭의 하드아웃> 야구장 사용 설명서: SK행복드림구장 편". 엠스플뉴스. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "잠실야구장 어떻게 달라졌나… 선수 숨소리까지 들려요 '익사이팅존' 생겨". news.kmib.co.kr. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- 엠스플뉴스. "<이동섭의 하드아웃> 야구장 사용 설명서: kt위즈파크 편". 엠스플뉴스. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "한화이글스, '스포츠 마케팅 어워드 코리아 2017'프로스포츠구단 부문 대상 : 스포츠동아". sports.donga.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- 세계일보 (2017-04-17). "입장권·용품 할인 듬뿍… "알뜰하게 스포츠 즐기세요"". 입장권·용품 할인 듬뿍… "알뜰하게 스포츠 즐기세요" - 세상을 보는 눈, 글로벌 미디어 - 세계닷컴 -. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "KIA타이거즈, 특석 및 가족석 신설" (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "NC다이노스 매트리스석 '비치타올' 등 무료 제공" (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "NC, 마산구장 좌석…팬 친화적으로 바꾼다". mk.co.kr. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "감염된 테란의 둥지 : 네이버 블로그". blog.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "롯데자이언츠 '신문지 응원' 전격 부활, 옛 분위기 살린다 - 스포츠Q(큐)" (in Korean). 2016-04-18. Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- "비닐봉지 머리에 쓰고 롯데 자이언츠 응원하는 바른정당". m.sports.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- "<정우영의 히든클립> 응원 로봇 '팬봇'을 아시나요?" (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-12-03.

- "감염된 테란의 둥지 : 네이버 블로그". blog.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- "'최강 기아'". m.sports.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- Spies-Gans, Juliet (2015-11-03). "Korean Baseball Fans' Coordinated Cheer Puts America To Shame". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- "테임즈 응원가 밀워키 상륙, 한국야구 문화 'MLB 진출' - 스포츠Q(큐)" (in Korean). 2017-05-03. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- NEWSIS. "[MLB]테임즈 맹활약에 NC 시절 응원가도 수출 조짐". newsis (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "밀워키 브루어스 "KBO팬, 테임즈 잊지 않았다"". www.kukinews.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- "프로야구 응원가 '저작권 침해'… 법정으로 가나". 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- "[이슈 진단] 야구 응원가 저작권 침해 '심각'…이젠 짚고 넘어갈 때" (in Korean). Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- "신종범 변호사의 법정이야기(76) - 응원가와 저작인격권 - 법률저널" (in Korean). 2017-04-14. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- "프로야구 롯데의 응원 문화 '아주라'…훈훈 VS 민폐". SBS NEWS (in Korean). 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- "'어우, 진짜 극혐!' 아주라 논쟁 촉발한 외국녀 영상". news.kmib.co.kr. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- "국내 첫 야구장 소음·빛 피해소송 내달 7일 변론 재개". 뉴스1 (in Korean). 2017-08-27. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- 박철홍 (2016-05-08). "야구장 야간조명에 "눈부셔 못살겠다" 고통 호소". 연합뉴스 (in Korean). Retrieved 2017-12-04.