Barwick, Hertfordshire

Barwick, Great Barwick, and Little Barwick (Berewyk 14th century, and Barrack[1] 19th century) are hamlets in the civil parish of Standon in Hertfordshire, England. They are near the A10 road and the village of Much Hadham and the hamlet of Latchford. The River Rib flows behind Barwick and through Great Barwick.[2] There is a ford crossing at Great Barwick.

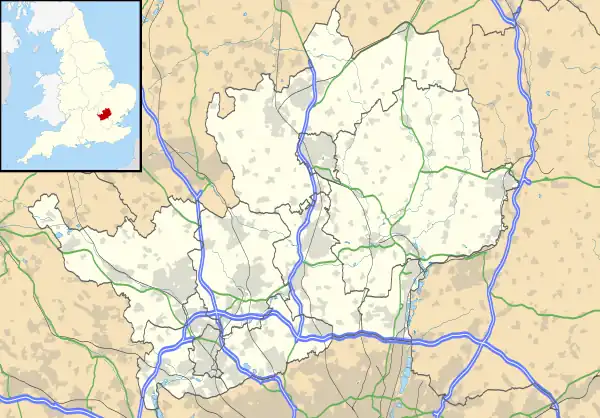

| Barwick | |

|---|---|

Barwick Location within Hertfordshire | |

| Population | 65 |

| OS grid reference | TL3819 |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Police | Hertfordshire |

| Fire | Hertfordshire |

| Ambulance | East of England |

History

In the 14th century, Barwick Manor, today known as Great Barwick Manor, was an estate and part of the larger Standon Manor and was in the king's name. The control was finally passed back to Sir William Say during the 16th century. Great Barwick hamlet predates the hamlet of Barwick.[2]

The settlement of Barwick, to the north of Great Barwick, was known as The Outpost.[3] In 1888, the Smokeless Powder Company (SPC), was founded by James Dalziel Dougall Jr, the son of the famous Glaswegian gunsmith J. D. Dougall,[4] took a 99-year lease for 126 acres around The Outpost,[1] from the Youngsbury Estate.[5] The site's name was changed from The Outpost to Barwick and Barwick was formed as a factory hamlet. SPC was to be the first modern producer of smokeless powders for the munitions industry.[6] As stated in the Los Angeles Herald on 11 November 1892:[7] "the only works of the kind in the kingdom". Its Head Office was based at Dashwood House, New Broad Street, London. It also had American agents based in New York and Boston.[8]

The factory hamlet was designed and superintended by the company's engineer Ernest Spon A.M.I.C.E.[9] Spon[10] was also an international author of civil engineering books, such as Workshop Receipts[11] and The Present Practice of Sinking and Boring Wells.[12] Spon also designed the Flameless Explosive Works at Denaby, near Rotherham.[13] Spon was interred at St John the Evangelist Church in High Cross village in 1890.[14] After he unexpectedly died from a stroke, in Aberdare, on 28 November 1890.[15]

SPC manufactured various high explosive powders for use in torpedoes, artillery shells, small arms ammunition (for the military and sporting) and mine blasting.[16] Their rifle line of powders was called Rifleite.[17] Rifleite was a completely gelatinised smokeless powder, made in the form of flakes.[18] A variety was also introduced for use in shotguns and was called Shot-Gun Rifleite. The company was a world leader in its high explosive powders and had over 100 employees. It was the first British company to export smokeless powders to the US.

SPC supplied smokeless powders and ammunition for some of the most important small arms and ammunition producers of the period: Holland & Holland, William Moore & Grey, W. W. Greener, Rigby,[19] Kynoch, Eley Brothers Ltd, Royal Small Arms factory, Winchester Repeating Arms Company, Remington Arms Company, LLC[20] and countless government armories with one special note with supplying the UK's Ministry of Munitions with smokeless powders for the Maxim and Gardner machine guns.[8] Dougall recounts the testing of the Maxim gun at the Barwick range.[19]

At 10:30 a.m. on 26 May 1893, there was an explosion and fire in drying house 15. Company employees A. Aylott and A. Ginn both died in this incident.[21] The accident was thoroughly investigated by H.M. Chief Inspector of Explosives, Colonel V. D. Majendie; on 20 June 1893.[22]

In 1892 SPC started to put the 1887 registered SPC into liquidation. SPC was re-registered in 1894 and underwent internal reorganization.[23] This reconstruction of the company might have been triggered by a trade mark litigation brought about by 'The Schultz Gunpowder Company Limited' in early 1892.[24] The litigation centered on exclusive rights to who owned the words 'smokeless powder'. On 1 January 1892, SPC incorporated a new company called The Smokeless Powder & Ammunition Company Limited.[25] This newly registered company may have come about in case the litigation went against SPC Also SPC won a contract to supply the Indian government[26] with Martin-Henry ammunition and probably wanted a company name to reflect that they were now producing ammunition. In 1892, SPC was not only producing smokeless powders but also producing, loading and selling directly the complete cartridge.[27]

On 15 January 1896, J. D. Dougall died. SPC's new chairman was M. S. Vanderbyl.[28] Vanderbyl was already a board director for SPC.[29]

In 1898, SPC was litigated by a Mr Heidemann who was the director of the Dynamite Nobel Trust.[30] Mr Heidemann accused SPC of patent infringement. SPC won the litigation because their chief chemist demonstrated that their nitro compound differed to that of Dynamite Nobel's. The litigation was a financial drain on SPC and as a result it went into liquidation.[31] In 1899, the Smokeless Powder Company was purchased by the New Schultze Gunpowder Company Limited,[32] located at Eyeworth, Fritham, Hampshire[33] As a result of the sale, the company was renamed the Smokeless Powder & Ammunition Company Limited.[34] Their 1900 catalogue lists all their products, along with extensive reviews on their powders' performances in The Field magazine.[35] The company employed two of the U.K.'s pioneering ballistics experts: Frederick William Jones OBE and R W S Griffith. Jones went onto to author the ground-breaking book on ballistics - The Hodsock Ballistic Tables For Rifles.[36] The company continued to produce high explosive powders until it ceased trading circa 1910 and was dissolved by 31 December 1916.[25] Its Head Office was located at 28 Gresham Street, London, E.C.[17]

Around 1912, Sabulite (Great Britain) Limited[37] (locally known and mapped as the Sabulite Works) took over the site and continued to produce high explosive materials, namely Sabulite and Cleveland Powder,[38] for military and civilian applications all over the world; especially for the Antipodes.[39] Sabulite was a blasting explosive containing ammonium nitrate, trinitro-toluene and calcium silicide.[18] The Belgian Sabulite Company,[40] who invented this explosive later modified the composition of their explosive for the mining industry.[41] Their product was extensively used in the First World War, especially in mortar warheads[42] and Mills bombs (hand grenades).[43] William Herbert McCandlish the director of the Sabulite Works patented a new hand grenade for use in the Great War[44] and a new cutting machine for cordite. The Sabulite Works went into liquidation circa 1933.[45]

After World War 2 the whole 126-acre site went up for auction. A former employee of the Sabulite company, Harry Sears,[46] purchased the 33-acre factory site in circa 1946. Sears had been employed by the company to be the gas engine driver. His role was to operate the tram system that ran over the whole 126-acre site. He was formerly employed in the same role at the Cotton Powder Company in Faversham,[47] until that site was shut down after an explosion on 2 April 1916[48] Sears utilised the existing factory buildings to open the Sabulite Snap Company,[49] which produced snaps for Christmas crackers. Sears was responsible for dismantling the whole tramway network.[49]

As of 2019, a lot of the archaeological remains of the original SPC site can be seen. In Cook's Wood and Round Wood, behind Barwick, stand the shells of the concrete magazines, with their blast mounts; along with the reservoir, bits of boundary fencing and the 400-yard rifle butts.[50] To the west of Round Wood in a grass meadow are the remains of three brick drying houses. There are also numerous foundations of buildings by the river Rib and the remains on the concrete bridge.[3] On the other side of the river Rib, on the factory site, there still exists some of the yellow brick factory buildings. Alongside the left-hand side of the factory runs the Barwick tributary. From the bridge there, on the right-hand side of the bank, lies one of the millstones used in the grinding process for the smokeless powder. All the residential building built in 1888–89 still stand.[51] The Douglas fir trees that briefly line Barwick Lane were planted for Mr J.D. Dougall JR, in 1889, so he did not feel homesick for his native Scotland.[52] The fields that run between the river Rib and residencies were used as a range, storage, testing/experimental work and disposal during SPC's and Sabulite's tenures.

On 4 April 2012, at Bonhams auctioneers, a rare 1 3/8in. punt gun by Wm.Moore & Grey no.2657 came up for sale.[53] This punt gun was mentioned in The Field magazine on 8 May 1897.[54] The gun was used to demonstrate the difference between black powder and SPC new product 303 Rifleite at the SPC range in Barwick. SPC ephemera, in general, is very scarce. A small quality of original boxes, cans and munitions were shown in an article written by Will Adye-White.[8]

Amenities

Barwick is made up of private residences, a caravan park and industrial units. There are no bus service, shops, telephone boxes, post offices or churches in Barwick. Barwick's public house was purposely built for the munition workers. It was initially named 'The Factory Arms'[52] but in circa 1904 the public house changed its name to The Duke of Wellington. The pub officially ceased trading in the late 1990s and is now a private residence.

References

- Footnotes

- Cassini maps of SG11 1DA dated 1805–1834

- British History Online - Barwick, Accessed 9 November 2013

- Cassini Maps of SG11 1DA dated 1898–1899

- The London Gazette 4 December 1894

- The Hertfordshire Mercury 1 June 1889

- The Times 16 April 1892

- Los Angeles Herald 11 November 1892

- IAA Journal Issue 444 July/August 2005 Adye-White, W.

- Graces Guide to British Industrial History

- Kelly's Directory 1890

- Workshop Receipts Spon, E.

- The Times 21 June 1881

- Barwick Gunpowder Works: A Note Storey, R Industrial Archaeology Pgs 275–77

- St John the Evangelist Church burial records

- Journal 1891 Pgs 214–5

- Greater Britain 15 December 1890

- The Smokeless Powder Ammunition Company, Limited catalogue 1900

- The Dictionary of Explosives Marshall, A.

- Iron 8 July 1892

- Nitro-Explosives a Practical Treatise Sanford, P.G. Pages 176–181

- HMIE Report

- Explosion of Drying-House at Smokeless Powder Factory Report, 26 May 1893

- The Times 23 March 1894'

- Reports of Patent, Design, and Trade Mark Cases. In the matter of the Smokeless Powder Company's Trade Mark. In the High Court of Justice -Chancery Division February 12 and 19 1892

- National Archives, Company No: 36183

- Iron 28 April 1893

- Nitro-Explosives Sanford, P.G. Pgs 176–181

- The Times 15 January 1896

- The London Gazette 1 November 1898

- Arms and Explosives: Heidemann v. The Smokeless Powder Co.Ltd. Pgs 130–134. May 1898

- The London Gazette 1 November 1898

- Barwick Gunpowder Works: A Note Storey, R Industrial Archaeology Pgs 275–277

- The Times 20 October 1899

- The Times 13 April 1901

- The Smokeless Powder & Ammunition Company Limited. 1900 Catalogue Pgs 1-33

- The Hodsock Ballistic Tables For Rifles Jones, F.W., O.B.E.

- List of Factories, &c., at which Explosives are Manufactured or Stored, Ministry of Munition 1915

- The Edinburgh Gazette 29 September 1925

- Report of the Chief Inspector of Explosives - Working of the Explosives Act during the year 1913 Victoria Australia

- The Argus 11 February 1915

- The London Gazette 23 June 1925

- Explanatory List of Service Marks D.G.M.D. General 287, 1918

- The Dominion 9 October 1915.

- Patent US 1234358A

- The London Gazette 3 February 1933

- 1911 England Census

- The Great Explosion at Faversham 2 April 1916

- Dillon, Brian (16 May 2015). "'The ghost of an awful energy' – the great Kent explosion of 1916". Retrieved 13 July 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- Barwick Gunpowder Works: A Note Storey, R Industrial Archaeology Pgs 275–8

- Dangerous Energy Cocroft, W.D. Pgs 127-8

- The Hertfordshire Mercury 8 June 1889

- The Hertfordshire Mercury 6 July 1889

- Bonhams Modern Sporting Gun sale 4 April 2012

- The Field 8 May 1897

- Sources

- Cassini maps of SG11 1DA dated 1805-1834.

- Jump up to:a b British History Online - Barwick, Accessed 9 November 2013.

- Cassini Maps of SG11 1DA dated 1898-1899.

- HMIE Report.

- Richard Storey Industrial Archaeology.

- The Times 10 August 1887.

- The Hertfordshire Mercury 1 June 1889.

- Guardian 10 September 1890.

- Greater Britain 15 December 1890.

- The Times 16 April 1892.

- Iron 8 July 1892.

- The Indianapolis News 14 September 1892.

- Los Angeles Herald 11 November 1892.

- Explosion of Drying-House at Smokeless Powder Factory Report, 26 May 1893.

- The Times 15 January 1896.

- The London Gazette 4 November 1898.

- The Dominion 9 October 1915.

- New Zealand Herald 11 October 1915.

- Patent US 1234358A

- Explanatory List of Service Marks D.G.M.D. General 287, 1918.

- The Dictionary of Explosives Marshall, A.

- The Hodsock Ballistic Tables For Rifles Jones, F.W., O.B.E.

- Dangerous Energy Cocroft, W.D.

- List of Factories, &c., at which Explosives are Manufactured or Stored, Ministry of Munition 1915.

- British Cartridge Manufacturers, Loaders and Retailers Harding, C.W.

- IAA Journal Issue 444 July/August 2005 Adye-White, W.

- 1911 England Census

External links

![]() Media related to Barwick, Hertfordshire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Barwick, Hertfordshire at Wikimedia Commons