Varahi

Varahi (Sanskrit: वाराही, Vārāhī)[note 1] is one of the Matrikas, a group of seven mother goddesses in the Hindu religion. Bearing the head of a sow, Varahi is the shakti (feminine energy) of Varaha, the boar avatar of the god Vishnu. In Nepal, she is called Barahi. In Rajasthan and Gujarat, she is venerated as Dandini.

| Varahi | |

|---|---|

Commander of the Matrikas | |

A contemporary image of Varahi | |

| Other names | Varthali, Dandini Devi, Dhandai Mata, Verai |

| Devanagari | वाराही |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Vārāhī |

| Affiliation | Matrikas, Devi, Lakshmi |

| Abode | Vaikuntha |

| Mantra | Om Varahmukhi Vidhmahe Dandanathae Dhimahi Tanno Devi Prachodayat |

| Weapon | Plough and pestle |

| Mount | Buffalo |

| Consort | Vishnu as Varaha |

Varahi is more commonly venerated in the sect of the Goddess-oriented Shaktism, but also in Shaivism (devotees of Shiva) and Vaishnavism (devotees of Vishnu). She is usually worshipped at night, using secretive Vamamarga Tantric practices. The Buddhist goddesses Vajravārāhī and Marichi have their origins in the Hindu goddess Varahi.

Legend

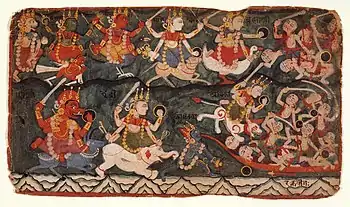

According to the Shumbha-Nishumbha story of the Devi Mahatmya from the Markandeya Purana religious texts, the Matrikas goddesses appears as shaktis (feminine powers) from the bodies of the gods. The scriptures say Varahi was created from Varaha. She has a boar form, wields a chakra (discus) and fights with a sword.[1][2] After the battle described in the scripture, the Matrikas dance – drunk on their victim's blood.[3]

According to a latter episode of the Devi Mahatmya that deals with the killing of the demon Raktabija, the warrior-goddess Durga creates the Matrikas from herself and with their help slaughters the demon army. When the demon Shumbha challenges Durga to single combat, she absorbs the Matrikas into herself.[4] In the Vamana Purana, the Matrikas arise from different parts of the Divine Mother Chandika; Varahi arises from Chandika's back.[2][5]

The Markendeya Purana praises Varahi as a granter of boons and the regent of the Northern direction, in a hymn where the Matrikas are declared as the protectors of the directions. In another instance in the same Purana, she is described as riding a buffalo.[6] The Devi Bhagavata Purana says Varahi, with the other Matrikas, is created by the Supreme Mother. The Mother promises the gods that the Matrikas will fight demons when needed. In the Raktabija episode, Varahi is described as having a boar form, fighting demons with her tusks while seated on a preta (corpse).[7]

In the Varaha Purana, the story of Raktabija is retold, but here each of Matrikas appears from the body of another Matrika. Varahi appears seated on Shesha-nāga (the serpent on which the god Vishnu sleeps) from the posterior of Vaishnavi, the Shakti of Vishnu.[8] Varahi is said to represent the vice of envy (asuya) in the same Purana.[9][10]

The Matsya Purana tells a different story of the origin of Varahi. Varahi, with other Matrikas, is created by Shiva to help him kill the demon Andhakasura, who has the ability – like Raktabija – to regenerate from his dripping blood.[8]

Associations

The Devi Purana paradoxically calls Varahi the mother of Varaha (Varahajanani) as well as Kritantatanusambhava, who emerges from Kritantatanu. Kritantatanu means "death personified" and could be an attribute of Varaha or a direct reference to Yama, the god of death.[11] Elsewhere in the scripture, she is called Vaivasvati and described as engrossed in drinking from a skull-cup. Pal theorizes that the name "Vaivasvati" means that Varahi is clearly identified with Yami, the shakti of Yama, who is also known as Vivasvan. Moreover, Varahi holds a staff and rides a buffalo, both of which are attributes of Yama; all Matrikas are described as having the form of the gods, they are shaktis of.[12]

In the context of the Matrikas' association to the Sanskrit alphabet, Varahi is said to govern the pa varga of consonants, namely pa, pha, ba, bha, ma.[13] The Lalita Sahasranama, a collection of 1,000 names of the Divine Mother, calls Varahi the destroyer of demon Visukaran.[14] In another context, Varahi, as Panchami, is identified with the wife of Sadashiva, the fifth Brahma, responsible for the regeneration of the Universe. The other Panch Brahmas ("five Brahmas") are the gods Brahma, Govinda, Rudra and Isvara, who are in charge of creation, protection, destruction and dissolution respectively.[10] In yet another context, Varahi is called Kaivalyarupini, the bestower of Kaivalya ("detachment of the soul from matter or further transmigrations") – the final form of mukti (salvation).[10] The Matrikas are also believed to reside in a person's body. Varahi is described as residing in a person's navel and governs the manipura, svadhisthana and muladhara chakras.[15]

Haripriya Rangarajan, in her book Images of Varahi—An Iconographic Study, suggests that Varahi is none other than Vak devi, the goddess of speech.[16]

Iconography

Varahi's iconography is described in the Matsya Purana and agamas, such as the Purva-karnagama and the Rupamandana.[17] The Tantric text Varahi Tantra mentions that Varahi has five forms: Svapna Varahi, Canda Varahi, Mahi Varahi (Bhairavi), Krcca Varahi and Matsya Varahi.[10][18] The Matrikas, as shaktis of gods, are described to resemble those gods in form, jewellery and mount, but Varahi inherits only the boar-face of Varaha.[19]

Varahi is usually depicted with her characteristic sow face on a human body with a black complexion comparable to a storm cloud.[8][20] The scholar Donaldson informs us that the association of a sow and a woman is seen as derogatory for the latter, but the association is also used in curses to protect "land from invaders, new rulers and trespassers".[19] Occasionally, she is described as holding the Earth on her tusks, similar to Varaha.[2] She wears the karaṇḍa mukuṭa, a conical basket-shaped crown.[8][17] Varahi can be depicted as standing, seated, or dancing.[16] Varahi is often depicted as pot-bellied and with full breasts, while most all other Matrikas – except Chamunda – are depicted as slender and beautiful.[19][21] One belief suggests that since Varahi is identified with the Yoganidra of Vishnu, who holds the universe in her womb (Bhugarbha Paranmesvari Jagaddhatri), she should be shown as pot-bellied.[10][16] Another theory suggests that the pot-belly reflects a "maternal aspect", which Donaldson describes as "curious" because Varahi and Chamunda "best exemplify" the terrible aspect of the Divine Mother.[19] A notable exception is the depiction of Varahi as human-faced and slender at the sixth-century Rameshvara cave (Cave 21), the Ellora Caves. She is depicted here as part of the group of seven Matrikas.[22] A third eye and/or a crescent moon is described to be on her forehead.[2][10]

Varahi may be two, four, six or eight-armed.[10][17] The Matsya Purana, the Purva-karnagama and the Rupamandana mention a four-armed form. The Rupamandana says she carries a ghanta (bell), a chamara (a yak's tail), a chakra (discus) and a gada (mace). The Matsya Purana omits the ghanta and does not mention the fourth weapon.[2][17][23] The Purva-Karanagama mentions that she holds the Sharanga (the bow of Vishnu), the hala (plough) and the musula (pestle). The fourth hand is held in the Abhaya ("protection gesture") or the Varada Mudra ("blessing gesture").[8][17] The Devi Purana mentions her attributes as being sword, iron club and noose. Another description says her hair is adorned with a garland with red flowers. She holds a staff and drinking skull-cup (kapala).[12][20] The Varahini-nigrahastaka-stotra describes her attributes as a plough, a pestle, a skull-cup and the abhaya mudra.[24] The Vamana Purana describes her seated on Shesha while holding a chakra and a mace.[2] The Agni Purana describes her holding the gada, shankha, sword and ankusha (goad).[2] The Mantramahodadhi mentions she carries a sword, shield, noose and goad.[2] In Vaishnava images, since she is associated with Vishnu, Varahi may be depicted holding all four attributes of Vishnu – Shankha (conch), chakra, Gada and Padma (lotus).[16] The Aparajitapriccha describes her holding a rosary, a khatvanga (a club with a skull), a bell, and a kamandalu (water-pot).[24]

The Vishnudharmottara Purana describes a six-armed Varahi, holding a danda (staff of punishment), khetaka (shield), khadga (sword) and pasha (noose) in four hands and the two remaining hands being held in Abhaya and Varada Mudra ("blessing gesture").[8] She also holds a shakti and hala (plough). Such a Varahi sculpture is found at Abanesi, depicted with the dancing Shiva.[8] She may also be depicted holding a child sitting on her lap, as Matrikas are often depicted.[16][22]

Matsya Varahi is depicted as two-armed, with spiral-coiled hair and holding a fish (matsya) and a kapala. The fish and wine-cup kapala are special characteristics of Tantric Shakta images of Varahi, the fish being exclusive to Tantric descriptions.[10][18]

The vahana (vehicle) of Varahi is usually described as a buffalo (Mahisha). In Vaishnava and Shakta images, she is depicted as either standing or seated on a lotus pitha (pedestral) or on her vahana (a buffalo) or on its head, or on a boar, the serpent Shesha, a lion, or on Garuda (the eagle-man vahana of Vishnu). In Tantric Shakta images, the vahana may be specifically a she-buffalo or a corpse (pretasana).[10][16][17][20][24] An elephant may be depicted as her vahana.[8] The goddess is also described as riding on her horse, Jambini.[25] Garuda may be depicted as her attendant.[21] She may also be depicted seated under a kalpaka tree.[8]

When depicted as part of the Sapta-Matrika group ("seven mothers"), Varahi is always in the fifth position in the row of Matrikas, hence called Panchami ("fifth"). The goddesses are flanked by Virabhadra (Shiva's fierce form) and Ganesha (Shiva's elephant-headed son and wisdom god).[10]

Worship

Varahi is worshipped by Shaivas, Vaishnavas and Shaktas.[16] Varahi is worshipped in the Sapta-Matrikas group ("seven mothers"), which are venerated in Shaktism, as well as associated with Shiva.

Varahi is a ratri devata (night goddess) and is sometimes called Dhruma Varahi ("dark Varahi") and Dhumavati ("goddess of darkness"). According to Tantra, Varahi should be worshipped after sunset and before sunrise. Parsurama Kalpasutra explicitly states that the time of worship is the middle of the night.[10] Shaktas worship Varahi by secretive Vamamarga Tantric practices,[16] which are particularly associated with worship by panchamakara – wine, fish, grain, meat and ritual copulation. These practices are observed in the Kalaratri temple on the bank of the Ganges, where worship is offered to Varahi only in the night; the shrine is closed during the day.[16] Shaktas consider Varahi to be a manifestation of the goddess Lalita Tripurasundari or as "Dandanayika" or "Dandanatha" – the commander-general of Lalita's army.[16] The Sri Vidya tradition of Shaktism elevates Varahi to the status of Para Vidya ("transcendental knowledge").[16] The Devi mahatmya suggests evoking Varahi for longevity.[10] Thirty yantras and thirty mantras are prescribed for the worship of Varahi and to acquire siddhis by her favour. This, according to the scholar Rath, indicates her power. Some texts detailing her iconography compare her to the Supreme Shakti.[10]

Prayers dedicated to Varahi include Varahi Anugrahashtakam, for her blessing, and Varahi Nigrahashtakam, for destruction of enemies; both are composed in Tamil.[26][27]

Temples

Apart from the temples in which Varahi is worshipped as part of the Sapta-Matrika, there are notable temples where Varahi is worshipped as the chief deity.

- India

A 9th-century Varahi temple exists at Chaurasi about 14 km from Konark, Orissa, where Varahi is installed as Matysa Varahi and is worshipped by Tantric rites.[10][28] In Varanasi, Varahi is worshipped as Patala Bhairavi. In Chennai, there is a Varahi temple in Mylapore, while a larger temple is being built near Vedanthangal.[25] Ashadha Navaratri, in the Hindu month of Ashadha (June/July), is celebrated as a nine-day festival in honour of Varahi at the Varahi shrine at Brihadeeswarar temple (a Shaiva temple), Thanjavur. The goddess is decorated with different types of alankarams (ornaments) every day, during festivals while full moon days are also considered auspicious.[14] An ancient temple of the goddess is also found at Uthirakosamangai.[29] Ashta-Varahi temple with eight forms of Varahi is situated in Salamedu near Villupuram.[30]

- Nepal

The Tal Barahi Temple is situated in the middle of Phewa Lake, Nepal. Here, Barahi, as she is known as in Nepal, is worshipped in the Matysa Varahi form as an incarnation of Durga and an Ajima ("grandmother") goddess. Devotees usually sacrifice male animals to the goddess on Saturdays.[31] Jaya Barahi Mandir, Bhaktapur, is also dedicated to Barahi.[32]

Outside Hinduism

Vajravarahi ("vajra-hog" or Buddhist Varahi), the most common form of the Buddhist goddess Vajrayogini, originated from the Hindu Varahi. Vajravarahi is also known as Varahi in Buddhism. Vajravarahi inherits the fierce character and wrath of Varahi. Both are invoked to destroy enemies. The sow head of Varahi is also seen as the right-side head attached to the main head in one of Vajravarahi's most common forms. The hog head is described in Tibetan scriptures as representing the sublimation of ignorance ("moha"). According to Elizabeth English, Varahi enters the Buddhist pantheon through the yogatantras. In the Sarvatathagatatattvasamgaraha, Varahi is described initially as a Shaiva sarvamatr ("all-mother") located in hell, who is converted to the Buddhist mandala by Vajrapani, assuming the name Vajramukhi ("vajra-face"). Varahi also enters the Heruka-mandala as an attendant goddess. Varahi, along with Varttali (another form of Varahi), appears as the hog-faced attendant of Marichi, who also has a sow face – which may be an effect of the Hindu Varahi.[16][33]

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

- Kinsley p. 156, Devi Mahatmya verses 8.11–20

- Donaldson p. 158

- Kinsley p. 156, Devi Mahatmya verses 8.62

- Kinsley p. 158, Devi Mahatmya verses 10.2–5

- Kinsley p. 158, verses 30.3–9

- Moor, Edward (2003). "Sacti: Consorts or Energies of Male Deities". Hindu Pantheon. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. pp. 25, 116–120. ISBN 978-0-7661-8113-7.

- Swami Vijnanananda (1923). The Sri Mad Devi Bhagavatam: Books One Through Twelve. Allahabad: The Panini Office. pp. 121, 138, 197, 452–7. ISBN 9780766181670. OCLC 312989920.

- Goswami, Meghali; Gupta, Ila; Jha, P. (March 2005). "Sapta Matrikas in Indian Art and Their Significance in Indian Sculpture and Ethos: A Critical Study" (PDF). Anistoriton Journal. Anistoriton. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- Kinsley p. 159, Varaha Purana verses 17.33–37

- Rath, Jayanti (September–October 2007). "The Varahi Temple of Caurasi". Orissa Review. Government of Orissa: 37–9.

- Pal pp. 1844–5

- Pal p.1849

- Padoux, André (1990). Vāc: the Concept of the Word in Selected Hindu Tantras. Albany: SUNY Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-7914-0257-3.

- Srinivasan, G. (24 July 2007). "Regaling Varahi with Different 'Alankarams in 'Ashada Navaratri'". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- Sri Chinmoy (1992). Kundalini: the Mother-Power. Jamaica, NY: Aum Publications. p. 18. ISBN 9780884971047.

- Nagaswamy, R (8 June 2004). "Iconography of Varahi". The Hindu. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- Kalia, Asha (1982). Art of Osian Temples: Socio-Economic and Religious Life in India, 8th–12th Centuries A.D.. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. pp. 108–10. ISBN 0-391-02558-9.

- Donaldson p. 160

- Donaldson p. 155

- Pal p. 1846

- Bandyopandhay p. 232

- Images at Berkson, Carmel (1992). Ellora, Concept and Style. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. pp. 144–5, 186. ISBN 81-7017-277-2.

- Rupamandana 5.67-8, Matsya Purana 261.30

- Donaldson p. 159

- Swaminathan, Chaitra (1 December 2009). "Presentation on Varahi". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 15 December 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- Ramachander (Translation), P. R. (2002–2010). "Varahi Anugrahashtakam". Vedanta Spiritual Library. Celextel Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- Ramachander (Translation), P. R. (2002–2010). "Varahi Nigrahashtakam (The Octet of Death Addressed to Varahi)". Vedanta Spiritual Library. Celextel Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- "Destinations: Konark". Tourism Department, Government of Orissa. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- "ராமநாதபுரம் வராஹி அம்மன் கோவிலில் வருடாபிஷேக விழா || Varahi Amman temple festival". Maalaimalar. 4 February 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- "இழந்த செல்வத்தை வழங்கும் வராகி அம்மன் || varahi amman". Maalaimalar. 10 April 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- "Barahi Temple on Phewa Lake". Channel Nepal site. Paley Media, Inc. 1995–2010. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- Reed, David; McConnachie, James (2002). "The Kathmandu Valley: Bhaktapur". The Rough Guide to Nepal. Rough Guides. London: Rough Guides. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-85828-899-4.

- English, Elizabeth (2002). "The Emergence of Vajrayogini". Vajrayoginī: Her Visualizations, Rituals and Forms. Boston: Wisdom Publications. pp. 47–9, 66. ISBN 978-0-86171-329-5.

References

- Bandyopandhay, Sudipa (1999). "Two Rare Matrka Images from Lower Bengal". In Mishra, P. K. (ed.). Studies in Hindu and Buddhist Art. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-368-7.

- Donaldson, Thomas Eugene (1995). "Orissan Images of Vārāhī, Oḍḍiyāna Mārīcī and Related Sow-Faced Goddesses". Artibus Asiae. Artibus Asiae Publishers. 55 (1/2): 155–182. doi:10.2307/3249765. JSTOR 3249765. OCLC 483899737.

- Kinsley, David (1987). Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0394-9.

- Pal, P. (1997). "The Mother Goddesses According to the Devipurana". In Singh, Nagendra Kumar (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism. New Delhi: Anmol Publications. ISBN 81-7488-168-9.