Bangime language

Bangime (/ˌbæŋɡiˈmeɪ/; bàŋɡí–mɛ̀, or, in full, Bàŋgɛ́rí-mɛ̀)[2] is a language isolate spoken by 3,500[1] ethnic Dogon in seven villages in southern Mali, who call themselves the bàŋɡá–ndɛ̀ ("hidden people"). Bangande is the name of the ethnicity of this community and their population grows at a rate of 2.5% per year.[3] The Bangande consider themselves to be Dogon, but other Dogon people insist they are not.[4][5] Bangime is an endangered language classified as 6a - Vigorous by Ethnologue.[6] Long known to be highly divergent from the (other) Dogon languages, it was first proposed as a possible isolate by Blench (2005). Heath and Hantgan have hypothesized that the cliffs surrounding the Bangande valley provided isolation of the language as well as safety for Bangande people.[7] Even though Bangime is not closely related to Dogon languages, the Bangande still consider their language to be Dogon.[4] Hantgan and List report that Bangime speakers seem unaware that it is not mutually intelligible with any Dogon language.[8]

| Bangime | |

|---|---|

| Baŋgɛri-mɛ | |

| Native to | Mali |

| Region | Dogon cliffs |

Native speakers | 3,500 (2017)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | dba |

| Glottolog | bang1363 |

| ELP | Bangime |

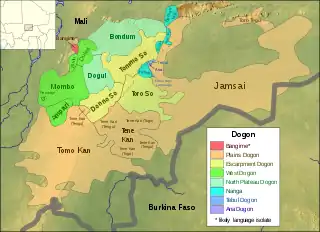

Bangi-me, among the Dogon languages | |

Bangime Location in Mali | |

| Coordinates: 14.81°N 3.77°W | |

Roger Blench, who discovered the language was not a Dogon language, notes,

- This language contains some Niger–Congo roots but is lexically very remote from all other languages in West Africa. It is presumably the last remaining representative of the languages spoken prior to the expansion of the Dogon proper,

which he dates to 3,000–4,000 years ago.

Bangime has been characterised as an anti-language, i.e., a language that serves to prevent its speakers from being understood by outsiders, possibly associated with the Bangande villages having been a refuge for escapees from slave caravans.[8]

Blench (2015) speculates that Bangime and Dogon languages have a substratum from a "missing" branch of Nilo-Saharan that had split off relatively early from Proto-Nilo-Saharan, and tentatively calls that branch "Plateau".[9]

Locations

Health and Hantgan report that Bangime is spoken in the Bangande valley, which cuts into the western edge of the Dogon high plateau in eastern Mali. Blench reports that Bangime is spoken in 7 villages east of Karge, near Bandiagara, Mopti Region, central Mali (Blench 2007). The villages are:

Morphology

Bangime uses various morphological processes, including clitics, affixation, reduplication, compounding, and tone change.[11] It does not use case-marking for noun phrase subjects and objects.[12] Bangime is a largely isolating language. The only productive affixes are the plural and a diminutive, which are seen in the words for the people and language above.

Affixation

Bangime has both prefixation and suffixation. The following chart provides examples of affixation.[13]

| Suffixation | Prefixation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possessor-of-X Derivative Suffix | Agentive Suffix | Causative Suffix | Pluralization Suffix | 'Thing' Prefix to Nouns |

sjɛ̀ɛ̀ⁿ-tjɛ́ɛ́ⁿ force, power-possessor-of-X derivative ‘soldier, policeman’[14] |

ɲɔ̀ŋɔ̀ndɔ̀-ʃɛ̀ɛ̀ⁿ write-AGT ‘writer, scribe’[15] |

twàà-ndà arrive-CAUS ‘deliver (message, object)’[16] |

bùrⁿà-ndɛ́ stick-PL ‘sticks’[17] |

kì-bɛ́ndɛ́ thing-long ‘something long, a long one’[18] |

Compounding

Bangime creates some words by compounding two morphemes together. A nasal linker is often inserted between the two morphemes. This linker matches the following consonant's place of articulation, with /m/ used before labials, /n/ before alveolars, and /ŋ/ before velars.[19] Below are examples of compound words in Bangime.

tàŋà-m̀-bógó

ear-(linker)-wide

‘elephant’[20]

náá-ḿ-bííⁿ

bush/outback-(linker)-goat

'wild goat’[21]

Reduplicative compounds

Some compound words in Bangime are formed by full or partial reduplication. The following chart contains some examples. In the chart, v indicates a vowel (v̀ is a low tone, v̄ is a mid tone, v́ is a high tone), C indicates a consonant, and N indicates a nasal phoneme. Subscripts are used to show the reduplication of more than one vowel (v1 and v2). The repeated segment is shown in bold.[22] Partial reduplication is also seen alongside a change in vowel quality.[23] The chart also displays a few examples of this.

| Reduplication Structure | Reduplication Type | Example | Loose English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cv̀Cv̀-Cv́Cɛ̀ɛ̀ | Partial | dɔ̀rɔ̀-dɔ̀rɛ̀ɛ̀ | 'sand fox'[24] |

| Cv́N-CV(C)ɛ̀ɛ̀ | Partial | bóm-bòjɛ̀ɛ̀ | 'frog'[24] |

| Cv́1NCv́1-N-Cv́2NCɛ̀(ɛ̀) | Partial | béndé-ḿ-bándɛ̀ɛ̀ | 'vine'[24] |

| Cv̀N-Cv̀(C)ɛ̀ɛ̀ | Partial | pàm-pàⁿɛ̀ɛ̀ | 'stirring stick'[24] |

| Cv̀Cv̀-Cv́Cv́ | Full | jɔ̀rɔ̀-jɔ́rɔ́ | 'herb (Blepharis)'[25] |

| Cv̀1Cv̀1-Cv́2Cv̀2(C)ɛ̀ | Partial | jìgì-jágàjɛ̀ | 'chameleon'[25] |

| Cv̀N-Cv́NCv̄ | Partial | kɔ̀ŋ-kɔ́mbɛ̄ | 'pied crow'[26] |

| Cv́Cv́-NCv́Cv̀ | Partial | tímé-ń-tímɛ́ɛ̀ | 'bush (Scoparia)'[26] |

| Cv́1Cv́1-NCv́2Cv̀2 | Partial | kéré-ŋ́-kɑ́rⁿà | 'forked stick'[26] |

| Càà-Cɛ́ɛ́ | Partial | sààⁿ-sɛ́ɛ́ⁿ | 'Vachellia tortilis'[27] |

| Cìì-Cáá | Partial | ʒììⁿ-ʒááⁿ | 'tree (Mitragyna)'[25] |

| Cìì-CáCɛ̀ɛ̀ | Partial | ʒììⁿ-ʒáwⁿɛ̀ɛ̀ | 'bush (Hibiscus)'[25] |

Tone changes

Another morphological process used in Bangime is tone changes. One example of this is that the tones on vowels denote the tense of the word. For example, keeping the same vowel but changing a high tone to a low tone changes the tense from future to imperfective 1st person singular.[28]

dɛ́ɛ́ cultivate.FUT ‘cultivate (future tense)’ |

dɛ̀ɛ̀ cultivate.IPFV.1SG ‘I am cultivating’ |

Low tone is used for the tenses of imperfective 1st person singular, deontic, imperative singular, and perfective 3rd person singular. They are also used for perfective 3rd person singular along with an additional morpheme. High tone is used for the future tense.[28]

Phonology

Vowels

Bangime has 28 vowels. The chart below lists 7 short oral vowels, each of which can be long, nasalized, or both. All these vowel types can occur phonetically, but short nasalized vowels are sometimes allophones of oral vowels. This occurs when they are adjacent to nasalized semivowels (/wⁿ/ [w̃] and /jⁿ/ [j̃]) or /ɾⁿ/ [ɾ̃]. Long nasalized vowels are more common as phonemes than short nasalized vowels.[29]

Vowels have an ±ATR distinction, which affects neighbouring consonants, but unusually for such systems, there is no ATR vowel harmony in Bangime.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close-mid | e | o | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a |

Consonants

Bangime has 22 consonant phonemes, shown in the chart below. Consonants that appear in square brackets are the IPA symbol, when different from the symbol used by A Grammar of Bangime. A superscript "n" indicates a nasalized consonant. Sounds in parentheses are either allophones or limited to use in loanwords, onomatopoeias, etc.[30]

| Labial | Alveolar | Alveopalatal | Velar | Laryngeal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Stops/ Affricates |

plain | p [pʰ] | t [tʰ] | (tʃ) | k [kʰ] | |

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | g | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | (f) | s | (ʃ) | h | |

| voiced | (z) | ʒ | (ɣ) | |||

| Sonorants | oral | (ʋ) w | ɾ | j ɥ | ||

| nasal | wⁿ [w̃] | ɾⁿ [ɾ̃] | jⁿ [j̃] | |||

| Lateral | l | |||||

NC sequences tend to drop the plosive, and often lenite to a nasalized sonorant: [búndà] ~ [búr̃a] ~ [bún] 'finish', [támbà] ~ [táw̃à] ~ [támà] 'chew'.

/b/ and /ɡ/ appear as [ʋ] and [ɣ], depending on the ATR status of the adjacent vowels.

/s/ appears as [ʃ] before non-low vowels, /t/ and /j/ as [tʃ] and [ʒ] before either of the high front vowels. /j/ is realized as [dʒ] after a nasal.

Tone

Bangime uses high, mid, and low tone levels as well as contoured tones (used in the last syllable of a word).[31] There are three tones on moras(short syllables): high, low and rising. In addition, falling tone may occur on long (bimoraic) syllables. Syllables may also have no inherent tone. Each morpheme has a lexical tone melody of /H/, /M/, or /L/ (high, mid, or low, respectively) for level tones or /LH/, /HL/, or /ML/ for contoured tones.[31] Nouns, adjectives, and numerals have lexical tone melodies. Terracing can also occur, giving a single level pitch to multiple words.[32] Stem morphemes (such as nouns and verbs) may contain tonal ablaut/stem-wide tone overlays.[31] For example, in nouns with determiners (definite or possessor), the determined form of the noun uses the opposite tone of the first tone in the lexical melody. A few examples of this process are listed in the chart below.[33]

| Melody | Undetermined Singular | Determined Plural | Loose English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| /L/ | bùrⁿà | DET búrⁿá-ndɛ̀ | 'stick' |

| /LH/ | dʒɛ̀ndʒɛ́ | DET dʒɛ́ndʒɛ́-ndɛ̀ | 'crocodile' |

| /M/ | dījà | DET dìjà-ndɛ́ | 'village' |

| /ML/ | dāndì | DET dàndì-ndɛ́ | 'chilli pepper' |

| /H/ | párí | DET pàrì-ndɛ́ | 'arrow' |

| /HL/ | jáámbɛ̀ | DET jàà-ndɛ́ | 'child' |

Phrases and clauses can show tone sandhi.[32]

Syllable structure

Bangime allows for the syllable types C onset, CC onset, and C code, giving a syllable structure of (C)CV(C). The only consonants used as codas are the semivowels /w/ and /j/ and their corresponding nasalized phonemes. Usually, only monosyllabic words end in consonants.[30] The following chart displays examples of these syllable types. For words with multiple syllables, syllables are separated by periods and the syllable of interest is bolded.

| Syllable Type | Example | Loose English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| CV | kɛ́ | 'thing'[34] |

| CCV | bɔ̀.mbɔ̀.rɔ̀ | 'hat'[35] |

| CVC | dèj | 'grain'[36] |

Syntax

Basic word order

The subject noun phrase is always clause-initial in Bangime, apart from some clause-initial particles. In simple transitive sentences, SOV (subject, object, verb) word order is used for the present tense, imperfective and SVO (subject, verb, object) word order is used for the past tense, perfective.[12]

Examples of SOV word order

S

séédù

S

.

[∅

[3SG

.

dà]

IPFV]

.

[ā

[DEF

O

būrⁿà]

stick]

.

[ŋ̀

[3SG

V

kùmbò]

look.for.IPFV]

'Seydou is looking for the stick'

S

séédù

S

.

[∅

[3SG

.

dà]

IPFV]

.

[à

[DEF

O

dwàà]

tree]

.

[ŋ̀

[3SG

V

sɛ̀gɛ̀ɛ̀]

tilt.IPFV]

'Seydou is tilting the tree'

Examples of SVO word order

Intransitive sentences

.

[à

[DEF

S

jìbɛ̀-ndɛ́]

person-PL]

.

[∅

[3PL

.

kóó]

Pfv]

.

[ŋ́

[3PL

V

ʃààkā]

disperse]

.

[∅

[3PL

.

wāj̀]

Rslt]

'The people dispersed'

Word order in phrases

Below are some examples of word order in various phrases.

DETERMINER + NOUN PHRASE

POSSESSOR + POSSESSEE

NOUN PHRASE + ADPOSITION

Focalization

Bangime allows for the focalization of noun phrases, prepositional phrases, adverbs, and verbs.[51]

Verb focalization

gìgɛ̀ndì

sweep.VblN

[ŋ̀

[1SG

dá]

IPFV]

[ŋ́

[1SG

gìjɛ̀ndɛ̀]

sweep.Deon]

'Sweep(ing) [focus] is what I am doing/what I did'

Noun phrase focalization (Nonsubject)

séédù

Seydou

mí

1SGO

[ŋ́

[3SG

dɛ̄gɛ̀]

hit.Pfv1]

'It was me [focus] that I Seydou hit' Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Noun phrase focalization (Demonstrative)

Noun phrase focalization (Subject)

Adverbial focalization

ŋìjɛ̀

yesterday

[ŋ̀

[1SG

máá-rà]

build.Ipfv1]

[à

[DEF

kùwò]

house]

'It was yesterday [focus] that I built the house'

Prepositional phrase focalization

Polar interrogatives

Bangime uses [à], a clause-final particle, after a statement to make it a yes/no question. This particle is glossed with a Q. Below are some examples.[56]

[kúúⁿ

[market

ŋ́-kò]

Link-in]

[à

[2SG

wóré]

go.Pfv1]

à

Q

'Was it to the market [focus] that you-Sg went?'

séédù

S

à

Q

"Is it Seydou?'

[ŋ̀

[1SG

núú]

come.Pfv2]

má

here

à

Q

'Did I come here?'

Wh-questions

Wh-words are focalized in Bangime.[57] Below are some examples for these interrogatives.

Topic particle

The topic particle is [hɔ̀ɔ̀ⁿ] and this morpheme follows a noun phrase. The following example shows a topical constituent preceding a clause.[60]

[nɛ̀

[1PL

hɔ̀ɔ̄ⁿ]

TOP]

nɛ̀

1PL

[∅

[1PL

bè]

NEG]

[∅

[1PL

wóré]

go.IPFV]

'As for us, we aren't going'

"Only" particle

The morpheme [pàw] can mean either 'all' or 'only.' The following example shows this morpheme as an 'only' quantifier.[61]

[ŋ̀

[1SG

tí-jè]

sit.Pfv2]

pàw

only

'I merely sat down'

See also

- Bangime word list (Wiktionary)

References

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 3.

- Hantgan 2010.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 1-3.

- Hantgan, Abbie. “An Introduction to the Bangande People and the Bangime Phonology and Morphology.” 14 Aug. 2013.

- Hantgan-Sonko, Abbie (2013-08-14). "Introduction to the Bangime Language and Speakers". Indiana University Bloomington.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Bangime". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2019-03-22.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 5.

- Hantgan, Abbie; List, Johann-Mattis (2018-09-03), Bangime: Secret Language, Language Isolate, or Language Island?, retrieved 2021-10-29

- Blench, Roger. 2015. Was there a now-vanished branch of Nilo-Saharan on the Dogon Plateau? Evidence from substrate vocabulary in Bangime and Dogon. In Mother Tongue, Issue 20, 2015: In Memory of Harold Crane Fleming (1926-2015).

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 1.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 15.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, pp. 66, 97, 98, 211, 320.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 97.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 98.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 211.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 66.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 320.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 134.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 135.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 140.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 135-140.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 137-138.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 136.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 138.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 139.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 137.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 250.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 23.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 19.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 29.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 12.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 30.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 18.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 21.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 24.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 344.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 212.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 188.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 340.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 327.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 273.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 57.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 67.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 170.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 186.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 325.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 36.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 43.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 348.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 334.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 336.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 337.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 339.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 338.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 349.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 350.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 351.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 352.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 447.

- Heath & Hantgan 2018, p. 451.

Bibliography

- Blench, Roger, Bangime description and word list (2005)(2007)

- Hantgan, Abbie (2010). "A Grammar of Bangime (draft)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-06-18. Retrieved 2017-12-29.

- Hantgan, Abbie (July 2013). Aspects of Bangime phonology, morphology, and morphosyntax (Ph.D. thesis). Indiana University. hdl:2022/18024. OCLC 893980514.

- Heath, Jeffrey; Hantgan, Abbie (2018). A Grammar of Bangime. Mouton Grammar Library. ISBN 9783110557497. OCLC 1015349027.

External links

- Bangime Archived 2018-03-17 at the Wayback Machine at the Dogon languages and Bangime project