Eastern South Slavic

The Eastern South Slavic dialects form the eastern subgroup of the South Slavic languages. They are spoken mostly in Bulgaria and North Macedonia, and adjacent areas in the neighbouring countries. They form the so-called Balkan Slavic linguistic area, which encompasses the southeastern part of the dialect continuum of South Slavic.

| Eastern South Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Central and Eastern Balkans |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | east2269 |

Linguistic features

Languages and dialects

Eastern South Slavic dialects share a number of characteristics that set them apart from the other branch of the South Slavic languages, the Western South Slavic languages. This area consists of Bulgarian and Macedonian, and according to some authors encompasses the southeastern dialect of Serbian, the so-called Prizren-Timok dialect.[7] The last is part of the broader transitional Torlakian dialectal area. The Balkan Slavic area is also part of the Balkan Sprachbund. The external boundaries of the Balkan Slavic/Eastern South Slavic area can be defined with the help of some linguistic structural features. Among the most important of them are: the loss of the infinitive and case declension, and the use of enclitic definite articles.[8] In the Balkan Slavic languages, clitic doubling also occurs, which is characteristic feature of all the languages of the Balkan Sprachbund.[9] The grammar of Balkan Slavic looks like a hybrid of “Slavic” and “Romance” grammars with some Albanian additions.[10] The Serbo-Croatian vocabulary in both Macedonian and Serbian-Torlakian is very similar, stemming from the border changes of 1878, 1913, and 1918, when these areas came under direct Serbian linguistic influence.

Areal

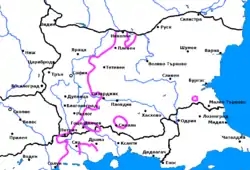

The external and internal boundaries of the linguistic sub-group between the transitional Torlakian dialect and Serbian and between Macedonian and Bulgarian languages are not clearly defined. For example, standard Serbian, which is based on its Western (Eastern Herzegovinian dialect), is very different from its Eastern (Prizren-Timok dialect), especially in its position in the Balkan Sprachbund.[11] During the 19th century, the Balkan Slavic dialects were often described as forming the Bulgarian language.[12] At the time, the areas east of Niš were considered under direct Bulgarian ethnolinguistic influence and in the middle of the 19th century, that motivated the Serb linguistic reformer Vuk Karadžić to use the Eastern Herzegovina dialects for his standardisation of Serbian.[13] Older Serbian scholars believed that the Yat border divides the Serbian and Bulgarian languages.[14] However, modern Serbian linguists such as Pavle Ivić have accepted that the main isoglosses bundle dividing Eastern and Western South Slavic runs from the mouth of the Timok river alongside Osogovo mountain and Sar Mountain.[15] In Bulgaria this isogloss is considered the eastern most border of the broader set of transitional Torlakian dialects.

In turn, Bulgarian linguists prior to World War II classified the Torlakian dialects or, in other words, all of Balkan Slavic (with the notable exception of the sub-dialects in Kosovo) as Bulgarian on the basis of their structural features, e.g., lack of case inflection, existence of a postpositive definite article and renarrative mood, use of clitics, preservation of final l, etc.[16][17][18] Individual researchers, such as Krste Misirkov, in one of his Bulgarian nationalist periods, and Benyo Tsonev have pushed the linguistic border even further west to include the Kosovo-Resava dialects or, in other words, all Serbian dialects having anlytical features.[19][20] Both countries currently accept the state border prior to 1919 to also be the boundary between the two languages.[21]

Defining the boundary between Bulgarian and Macedonian is even trickier. During much of its history, the Eastern South Slavic dialect continuum was simply referred to as "Bulgarian",[22] and Slavic speakers in Macedonia referred to their own language as balgàrtzki, bùgarski or bugàrski; i.e. Bulgarian.[23] However, Bulgarian was standardized at the end of the 19th century on the basis of its eastern Central Balkan dialect, while Macedonian was standardized in the middle of the 20th century using its west-central Prilep-Bitola dialect. Although some researchers still describe the standard Macedonian and Bulgarian languages as varieties of a pluricentric language, they have very different and remote dialectal bases.[24][17]

According to Chambers and Trudgill, the question whether Bulgarian and Macedonian are distinct languages or dialects of a single language cannot be resolved on a purely linguistic basis, but should rather take into account sociolinguistic criteria, i.e., ethnic and linguistic identity.[25] As for the Slavic dialects of Greece, Trudgill classifies the dialects in the east Greek Macedonia as part of the Bulgarian language area and the rest as Macedonian dialects.[26] Jouko Lindstedt opines that the dividing line between Macedonian and Bulgarian is defined by the linguistic identity of the speakers, i.e., the state border;[27] but has suggested the reflex of the back yer as a potential boundary if the application of purely linguistic criteria were possible.[28][29] According to Riki van Boeschoten, the dialects in eastern Greek Macedonia (around Serres and Drama) are closest to Bulgarian, those in western Greek Macedonia (around Florina and Kastoria) are closest to Macedonian, while those in the centre (Edessa and Salonica) are intermediate between the two.[30][31]

History

Some of the phenomena that distinguish western and eastern subgroups of the South Slavic people and languages can be explained by two separate migratory waves of different Slavic tribal groups of the future South Slavs via two routes: the west and east of the Carpathian Mountains.[32] The western Balkans was settled with Sclaveni, the eastern with Antes.[33] The early habitat of the Slavic tribes, that are said to have moved to Bulgaria, was described as being in present Ukraine and Belarus. The mythical homeland of the Serbs and Croats lies in the area of today Bohemia, in the present-day Czech Republic and in Lesser Poland. In this way, the Balkans were settled by different groups of Slavs from different dialect areas. This is evidenced by some isoglosses of ancient origin, dividing the western and eastern parts of the South Slavic range.

The extinct Old Church Slavonic, which survives in a relatively small body of manuscripts, most of them written in the First Bulgarian Empire during the 10th century, is also classified as Eastern South Slavic. The language has an Eastern South Slavic basis with small admixture of Western Slavic features, inherited during the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius to Great Moravia during the 9th century.[34] New Church Slavonic represents a later stage of the Old Church Slavonic, and is its continuation through the liturgical tradition introduced by its precursor. Ivo Banac maintains that during the Middle Ages, Torlak and Eastern Herzegovinian dialects were Eastern South Slavic, but since the 12th century, the Shtokavian dialects, including Eastern Herzegovinian, began to separate themselves from the other neighboring Eastern dialects, counting also Torlakian.[35]

The specific contact mechanism in the Balkan Sprachbund, based on the high number of second Balkan language speakers there, is among the key factors that reduced the number of Slavic morphological categories in that linguistic area.[36] The Primary Chronicle, written ca. 1100, claims that then the Vlachs attacked the Slavs on the Danube and settled among them. Nearly at the same time are dated the first historical records about the emerging Albanians, as living in the area to the west of the Lake Ohrid. There are references in some Byzantine documents from that period to "Bulgaro-Albano-Vlachs" and even to "Serbo-Albano-Bulgaro-Vlachs".[37] As a consequence, case inflection, and some other characteristics of Slavic languages, were lost in Eastern South Slavic area, approximately between the 11th–16th centuries. Migratory waves were particularly strong in the 16th–19th century, bringing about large-scale linguistic and ethnic changes on the Central and Eastern Balkan South Slavic area. They reduced the number of Slavic-speakers and led to the additional settlement of Albanian and Vlach-speakers there.

Separation between Macedonian and Bulgarian

The rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire began to degrade its specific social system, and especially the so-called Rum millet, through constant identification of the religious creed with ethnicity.[38] The national awakening of each ethnic group was complex and most of the groups interacted with each other.

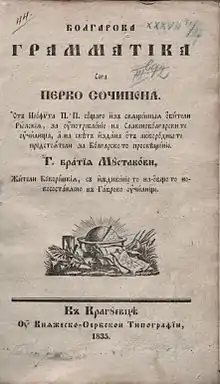

During the Bulgarian national revival, which occurred in the 19th century, the Bulgarian and Macedonian Slavs under the supremacy of the Greek Orthodox clergy wanted to create their own Church and schools which would use a common modern "Macedono-Bulgarian" literary standard, called simply Bulgarian.[39] The national elites active in this movement used mainly ethnolinguistic principles to differentiation between "Slavic-Bulgarian" and "Greek" groups.[40] At that time, every ethnographic subgroup in the Macedonian-Bulgarian linguistic area wrote in their own local dialect and choosing a "base dialect" for the new standard was not an issue. Subsequently, during the 1850s and 1860s a long discussion was held in the Bulgarian periodicals about the need for a dialectal group (eastern, western or compromise) upon which to base the new standard and which dialect that should be.[41] During the 1870s this issue became contentious, and sparked fierce debates.[42] The general opposition arose between Western and Eastern dialects in the Eastern South Slavic linguistic area. The fundamental issue then was in which part of the Bulgarian lands the Bulgarian tongue was preserved in a most true manner and every dialectal community insisted on that. The Eastern dialect was proposed then as a basis by the majority of the Bulgarian elite. It was claiming that around the last medieval capital of Bulgaria Tarnovo, the Bulgarian language was preserved in its purest form. It was not a surprise, because the most significant part of the new Bulgarian intelligentsia came from the towns of the Eastern Sub-Balkan valley in Central Bulgaria. This proposal alienated a considerable part of the then Bulgarian population and stimulated regionalist linguistic tendencies in Macedonia.[43] In 1870 Marin Drinov, who played a decisive role in the standardization of the Bulgarian language, practiclaly rejected the proposal of Parteniy Zografski and Kuzman Shapkarev for a mixed eastern and western Bulgarian/Macedonian foundation of the standard Bulgarian language, stating in his article in the newspaper Makedoniya: "Such an artificial assembly of written language is something impossible, unattainable and never heard of." and instead suggested that authors themselves use dialectal features in their work, thus becoming role models and allowing the natural development of a literary language.[44][45][46] In turn, this position was heavily criticised by Eastern Bulgarian scholars and authors such as Ivan Bogorov and Ivan Vazov, the latter of whom noting that "Without the beautiful words found in the Macedonia dialects, we will be unable to make our language either richer or purer."[47]

In this connection, it must be noted that the "Macedonian dialects" at the time generally referred to the Western Macedonian dialects rather than to all Slavic dialects in the geographic region of Macedonia. For example, scholar Yosif Kovachev from Štip in Eastern Macedonia proposed in 1875 that the "Middle Bulgarian" or "Shop dialect" of Kyustendil (in southwestern Bulgaria) and Pijanec (in eastern North Macedonia) be used as a basis for the Bulgarian literary language as a compromise and middle ground between what he himself referred to as the "Northern Bulgarian" or Balkan dialect and the "Southern Bulgarian" or "Macedonian" dialect.[48][45] Moreover, Southeastern Macedonia east of the ridges of the Pirin and then of a line stretching from Sandanski to Thessaloniki, which is located east of the Bulgarian Yat boundary and speaks Eastern Bulgarian dialects that are much more closely related to the Bulgarian dialects in the Rhodopes and Thrace than to the neighbouring Slavic dialects in Macedonia, largely did not participate at all in the debate as it was mostly Hellenophile at the time.[49][26][50]

In 1878, a distinct Bulgarian state was established. The new state did not include the region of Macedonia which remained outside its borders in the frame of the Ottoman Empire. As a consequence, the idea of a common compromise standard was finally rejected by the Bulgarian codifiers during the 1880s and the eastern Central Balkan dialect was chosen as a basis for standard Bulgarian.[51] Macedono-Bulgarian writers and organizations who continued to seek greater representation of Macedonian dialects in the Bulgarian standard were deemed separatists.[lower-alpha 1] One example is the Young Macedonian Literary Association, which the Bulgarian government outlawed in 1892. Though standard Bulgarian was taught in the local schools in Macedonia till 1913,[57] the fact of political separation became crucial for the development of a separate Macedonian language.[58]

With the advent of Macedonian nationalism, the idea of linguistic separatism emerged in the late 19th century,[59] and the need for a separate Macedonian standard language subsequently appeared in the early 20th century.[60] In the Interwar period, the territory of today's North Macedonia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Bulgarian was banned for use and the local vernacular fell under heavy influence from the official Serbo-Croatian language.[61] However, the political and paramilitary organizations of the Macedonian Slavs in Europe and the Americas, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) and the Macedonian Patriotic Organization (MPO), and even their left-wing offsets, the IMRO (United) and the Macedonian-American People's League continued to use literary Bulgarian in their writings and propaganda in the interbellum. During the World wars Bulgaria's short annexations over Macedonia saw two attempts to bring the Macedonian dialects back towards Bulgarian. This political situation stimulated the necessity of a separate Macedonian language and led gradually to its codification after the Second World War. It followed the establishment of SR Macedonia, as part of Communist Yugoslavia and finalized the progressive split in the common Macedonian–Bulgarian language.[62]

During the first half of the 20th century the national identity of the Macedonian Slavs shifted from predominantly Bulgarian to ethnic Macedonian and their regional identity had become their national one.[63][64][65] Although, there was no clear separating line between these two languages on level of dialect then, the Macedonian standard was based on its westernmost dialects. Afterwards, Macedonian became the official language in the new republic, Serbo-Croatian was adopted as a second official language, and Bulgarian was proscribed. Moreover, in 1946–1948 the newly standardized Macedonian language was introduced as a second language even in Southwestern Bulgaria.[66] Subsequently, the sharp and continuous deterioration of the political relationships between the two countries, the influence of both standard languages during the time, but also the strong Serbo-Croatian linguistic influence in Yugoslav era, led to a horizontal cross-border dialectal divergence.[67] Although some researchers have described the standard Macedonian and Bulgarian languages as varieties of a pluricentric language,[68] they in fact have separate dialectal bases; the Prilep-Bitola dialect and Central Balkan dialect, respectively. The prevailing academic consensus (outside of Bulgaria and Greece) is that Macedonian and Bulgarian are two autonomous languages within the eastern subbranch of the South Slavic languages.[69] Macedonian is thus an ausbau language; i.e. it is delimited from Bulgarian as these two standard languages have separate dialectal bases.[70][71][72] The uniqueness of Macedonian in comparison to Bulgarian is a matter of political controversy in Bulgaria.[73][74][75]

Differences between Macedonian and Bulgarian

Phonetics

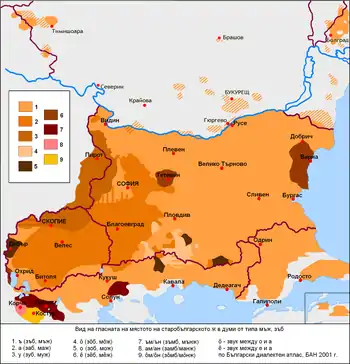

- Word stress in Macedonian is antepenultimate, meaning it falls on the third from last syllable in words with three or more syllables, on the second syllable in words with two syllables and on the first or only syllable in words with one syllable.[76] This means that Macedonian has fixed accent and for the most part automatically determined. Word stress in Bulgarian, just like Old Church Slavonic, is free and can fall on almost any syllable of the word, as well as on various morphological units like prefixes, roots, suffixes and articles. However, the easternmost dialects in North Macedonia like the Maleshevo dialect, the Dojran dialect and most Slavic dialects in Greece have free word stress.[77]

| Macedonian | Bulgarian | English |

|---|---|---|

| грáд | грáд | city |

| грáдот | градъ́т | the city |

| грáдови | градовé | cities |

| градóвите | градовéте | the cities |

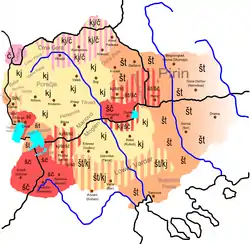

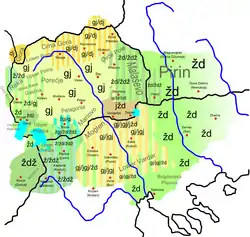

- Reflexes of Pra-Slavic *tʲ/kt and *dʲ: Bulgarian has kept the Old Church Slavonic reflexes щ /ʃt/ and жд /ʒd/ for Pra-Slavic *tʲ/kt and *dʲ, whereas Macedonian developed the velar ќ /c/ and ѓ /ɟ/ in their place under Serbian influence in the Late Middle Ages. However, many dialects in North Macedonia and the wider Macedonian region have retained the consonants or use the transitional шч /ʃtʃ/ and жџ /ʒdʒ/.

| Bulgarian | Macedonian | English |

|---|---|---|

| пращам [praʃtam] | праќам [pracam] | send |

| нощ [noʃt] | ноќ [noc] | night |

| раждам [raʒdam] | раѓам [raɟam] | give birth |

- Vowels: There are six vowels in Bulgarian, compared to five in Macedonian. While the schwa (ъ (/ɤ/) is part of standard Bulgarian phonology, it use in standard Macedonian is marginal.[78] Nevertheless, the schwa is phonemic in a number of Macedonian dialects, e.g. the Northern Macedonian dialects, the Ohrid dialect, the Upper Prespa dialect, etc., while it is missing from the phonetic inventory of a number of Western Bulgarian dialects, e.g., the Elin Pelin dialect, Vratsa dialect, Samokov dialect.[79][80][81] In other words, the difference is owing to a specific choice made during codification.

| Bulgarian | Macedonian | English |

|---|---|---|

| път [pɤt] | пат [pat] | road |

| сън [sɤn] | сон [sɔn] | dream |

| България [bəɫˈɡarijə] | Бугарија [buˈɡaɾi(j)a] | Bulgaria |

- Loss of х [h] in Macedonian: The development of the Macedonian dialects since the 16th century has been marked by the gradual disappearance of the x sound or its replacement by в [v] or ф [f] (шетах [šetah] → шетав [šetav]), whereas standard Bulgarian, just like Old Bulgarian/Old Church Slavonic, has kept х in all positions. However, most Bulgarian dialects, except for the southern Rup dialects, have lost х in most positions, as well.[83][84] The consonant was kept in the literary language for the sake of continuity with Old Bulgarian, i.e., the difference is again owing to a choice made during codification.

| Macedonian | Bulgarian | English |

|---|---|---|

| убава [ubava] | хубава [hubava] | beautiful |

| снаа [snaa] | снаха [snaha] | daughter-in-law |

| бев [bev] | бях [byah] | I was |

- Hard and palatalized consonants: Many consonant phonemes in the Slavic languages come in "hard" and "soft" pairs. However, at present, only four consonants in Macedonian have a "soft pair": /k/-/kʲ/, /g/-/gʲ/, /n/-/nʲ/, /l/-/lʲ/ plus the stand-alone glide j. At the same time, the situation in Bulgarian is extremely unclear, with older phonology handbooks claiming that almost every consonant in Bulgarian has a palatalised equivalent, and newer research asserting that this palatalisation is very weak and that the so-called "palatal consonants" in the literary language are actually pronounced as a sequence of consonant + glide j.[85][86] The reanalysis means that Bulgarian has only one palatal consonant, the semivowel j, which makes it the least palatal Slavic language.

| Bulgarian | Macedonian | English |

|---|---|---|

| бял [bʲa̟ɫ] or [bja̟ɫ] | бел [bɛɫ] | white |

| дядо [ˈdʲa̟do] or [ˈdja̟do] | дедо [ˈdɛdɔ] | grandfather |

| кестен [kɛstɛn] | костен [ˈkɔstɛn] | chestnut |

- The consonant group чр- [t͡ʃr-] in the beginning of the word, which was present in the Old Church Slavonic, predominantly was replaced with чер- in Bulgarian. In Macedonian this consonant group is replaced with цр-. There are examples that this process of replacing чр- with цр- was already happening in the 14th century in the Northern and Western Macedonian dialects.

| Macedonian | Bulgarian | English |

|---|---|---|

| цреша [ˈt͡srɛʃa] | череша [t͡ʃeˈrɛʃə] | cherry |

| црн [t͡sr̩n] | черен [ˈt͡ʃerɛn] | black |

| црта [ˈt͡sr̩ta] | черта [t͡ʃerˈta] | line |

Morphology

- Definite article: The Macedonian language has three definite articles pertaining to position of the object: unspecified, proximate (or close), and distal (or distant). All three have different gender forms, for masculine, feminine, and neuter nouns and adjectives. Bulgarian has only one definite article pertaining to unspecified position of the object. The difference is owing again to a choice made during codification: dialects in eastern North Macedonia have only one definite article, while there are dialects in Bulgarian that have triple definite article, such as the Tran dialect, Smolyan dialect, etc. Torlak dialects in Serba also have triple definite article.[87]

| Position | Macedonian | Bulgarian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| unspecified | собата | стаята | the room |

| proximate | собава | - | this room |

| distal | собана | - | that room |

| unspecified | собите | стаите | the rooms |

| proximate | собиве | - | this rooms |

| distal | собине | - | that rooms |

- Short and long definite articles: In Bulgarian, the masculine gender has two forms of definite articles: long (-ът, -ят) and short (-а, -я), depending on whether the noun has the role of subject or object in the sentence. The long form is used for a noun that's the subject of a sentence, while the short form is used for nouns that are direct/indirect objects. In Macedonian language, such a distinction is not made, and there is only the -от form for masculine nouns, besides, of course, the other two forms (-ов, -он) of the triple definite article.

- Example:

- Bulgarian

- Професорът е много умен. -The professor is very smart. (The professor is a subject → long form -ът)

- Видях професора. -I saw the professor. (The professor is a direct object → short form -а)

- Macedonian

- Професорот е многу паметен. -The professor is very smart.

- Го видов професорот. -I saw the professor.

- However, no Bulgarian dialect has both a short and a long definite article—all of them have either or. The rule is an entirely artificial construct suggested by one of the earliest Bulgarian men of letters, Neofit Rilski, himself from Pirin Macedonia, in an attempt to preserve the case system in Bulgarian.[88][89] For more than a century, this has been one of the most reviled grammatical rules in Bulgarian and has consistently been described as artificial, unnecessary and snobbish.

- Demonstrative pronouns: Similar to the article, the demonstrative pronouns in the Macedonian standard language have three forms: for pointing close objects and persons (овој, оваа, ова, овие), distant objects and persons (оној, онаа, она, оние) and pointing without spatial and temporal determination (тој, таа, тоа, тие). There are only two categories in the Bulgarian standard language: closeness (този/тоя, тази/тая, това/туй, тези/тия) and distance (онзи/оня, онази/оная, онова/онуй, онези/ония). For pointing objects and persons without spatial and temporal determination are used the same forms for closeness.

| Speaker | close distance | without spatial and temporal determination | farther away | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macedonian | Го гледам | ова дете | тоа дете | она дете |

| Bulgarian | Виждам | това дете | това дете | онова дете |

| English | I see | this child | the child | that child |

- Plural with the suffix -иња [inja] for neuter nouns: In the standard Macedonian language, some neuter nouns ending in -e form the plural with the suffix -иња.[90] In the Bulgarian language, neuter nouns ending in -e usually form the plural with the suffix -е(та) [-(e)ta] or -е(на) [-(e)na], and the suffix -иња does not exist at all.

| Macedonian | Bulgarian | English |

|---|---|---|

| море [more] мориња [morinja] | море [more] морета [moreta] | sea seas |

| име [ime] имиња [iminja] | име [ime] имена [imena] | name names |

- Present tense : Verbs of all three conjugations in Macedonian have unified ending -ам in 1st person singular: (пеам, одам, имам) for 1st person singular. In Bulgarian, 1st and 2nd conjugation use -а (-я): пея, ходя, and only 3rd conjugation uses - ам: имам.

- Past indefinite tense with има (to have): The standard Macedonian language is the only standard Slavic language in which there is a past indefinite tense (the so-called perfect), which is formed with the auxiliary verb to have and a verbal adjective in the neuter gender.[91] This grammatical tense in linguistics is called have-perfect and it can be compared to the present perfect tense in English, Perfekt in German and passé composé in French. This construction of има with a verbal adjective also exists in some non-standard forms of the Bulgarian language, but it is not part of the standard language and is not as developed and widespread as in Macedonian.

- Example: Гостите имаат дојдено. - The guests have arrived.

- Changing the root in some imperfect verb forms is characteristic only for the Bulgarian language. Like all Slavic languages, Macedonian and Bulgarian distinguish perfect and imperfect verb forms. However, in the Macedonian standard language, the derivation of imperfect verbs from their perfect pair takes place only with a suffix, and not with a change of the vowel in the root of the verb, as in the Bulgarian language.

| Bulgarian | Macedonian |

|---|---|

| отвори → отваря | отвори → отвора |

| скочи → скача | скокне → скока |

| изгори → изгаря | изгори → изгорува |

- Clitic doubling: Clitic doubling in the standard Macedonian language is always obligatory with definite direct and indirect objects, which contrasts with standard Bulgarian where clitic doubling is mandatory in a more limited number of cases.[92] Non-standard dialects of Macedonian and Bulgarian have differing rules regarding clitic doubling.

- Present active participle: All Slavic dialects in Bulgaria and Macedonia lost the Old Bulgarian present active participle ('сегашно деятелно причастие') in the Late Middle Ages. New Bulgarian readopted the participle from Church Slavonic in the 1800s, and it is currently used in the literary language. In spoken Bulgarian, it is replaced by a relative clause. Macedonian only uses a relative clause with the relative pronoun што.

- Example:

- Уплаших се от лаещите кучета. / Уплаших се от кучетата, които лаеха. - I was scared by the barking dogs./I was scared by the dogs that barked. (Bulgarian)

- Се исплашив од кучињата што лаеја - I was scared by the dogs that barked. (Macedonian)

- Conditional mood: In Bulgarian it is formed by a special form of the auxiliary 'съм' (to be) in conjugated form, and the aorist active participle of the main verb, while in Macedonian it is formed with the unconjugated form 'би' (would), and the aorist active participle of the main verb.

| person | gender and number | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m.sg. | f.sg. | n.sg. | pl. | |

| 1st | бѝх чѐл | бѝх чѐла | (бѝх чѐло) | бѝхме чѐли |

| 2nd | бѝ чѐл | бѝ чѐла | (бѝ чѐло) | бѝхте чѐли |

| 3rd | бѝ чѐл | бѝ чѐла | бѝ чѐло | бѝха чѐли |

| person | gender and number | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m.sg. | f.sg. | n.sg. | pl. | |

| 1st | би читал | би читала | би читало | би читале |

| 2nd | би читал | би читала | би читало | би читале |

| 3rd | би читал | би читала | би читало | би читале |

- Future-in-the-past: Both languages have this complex verb tense, but its formation differs.

In Bulgarian it is made up of the past imperfect of the verb ща (will, want) + the particle да (to) + the present tense of the main verb.

In Macedonian it is formed with the clitic ќе + imperfect of the verb.

Example (чета/чита, to read):

| person | number | |

|---|---|---|

| sg. | pl. | |

| 1st | щях да чета | щяхме да четем |

| 2nd | щеше да четеш | щяхте да четете |

| 3rd | щеше да чете | щяха да четат |

| person | number | |

|---|---|---|

| sg. | pl. | |

| 1st | ќе читав | ќе читавме |

| 2nd | ќе читаше | ќе читавте |

| 3rd | ќе читаше | ќе читаа |

Vocabulary

A primary objective of Bulgarian men of letters in the 1800s was to restore the Old Church Slavonic/Old Bulgarian vocabulary that had been lost or replaced with Turkish or Greek words during Ottoman rule through the mediation of Church Slavonic. Thus, originally Old Bulgarian higher-style lexis such as безплътен (incorporeal), въздържание (temperance), изобретател (inventor), изтребление (annihilation), кръвопролитие (bloodshed), пространство (space), развращавам (debauch), създание (creature), съгражданин (fellow citizen), тщеславие (vainglory), художник (painter), was re-borrowed in the 1800s from Church Slavonic and Russian, where it had been adopted in the Early Middle Ages.[93][94][95]

There are 12 phono-morpohological that point at the Old Bulgarian origin of a word in Church Slavonic or Russian:[96]

- Use of the Bulgarian reflexes щ and жд for Pra-Slavic *tʲ/kt and *dʲ instead of the native Russian ones ч /tɕ/ and ж /ʑ/, e.g., заблуждать (mislead), влагалище (vagina);

- Replacement of East Slavic pleophonic -olo/-oro with -la/-ra. Thus, East Slavic forms such as голова (head) and город (city) exist side by side with Old Bulgarian главный (primary) and гражданин (citizen);

- Use of word-initial a, e, ю, ра and la, e.g., единовластие (absolutism) rather than одиноволостие, which would be the expected form based on East Slavic phonology, юность (youth), which replaced Old Russian ѹность, работа (work), which replaced Old Russian робота;

- Use of prefixes such as воз- and пре- instead of the native East Slavic вз- and пере-, e.g., воздержание (abstention) or преображать/преобразить (transform);

- Use of Old Bulgarian suffixes such as -тель, -тельность, -ствие, -енство, -ес, -ание, -ащий, -ущий, -айший, -ение, -ейший, e.g., благоденствие (prosperity), упражнение (exercise), пространство (space), стремление (aspiration), etc. etc. that can be traced back to use in Old Bulgarian manuscripts.

- Etc.

Nevertheless, none of this went without a problem. In the end, a number of Russified Old Bulgarisms replaced preserved native Old Bulgarisms, e.g., the Russified невежа and госпожа ("ignoramus" & "Madam") replaced the native невежда and госпожда, a number of other words were adopted with Russified phonology, e.g., утроба (O.B. ѫтроба, "uterus") rather than ътроба or вътроба, свидетел (O.B. съвѣдѣтель, "withness") rather than сведетел, началник (O.B. начѧльникъ, "superior") rather than начелник—which is what would have been expected given the phonetic development of the Bulgarian language, others had changed their meaning completely, e.g., опасно (O.B. опасьно) readopted in the meaning of "dangerously" rather than "meticulously", урок (O.B. ѹрокъ) readopted in the meaning of "lesson" rather than "condition"/"proviso", yet many, many others that ended up being Russian or Church Slavonic new developments on the basis of Old Bulgarian roots, suffixes, prefixes, etc.

Unlike Bulgarian, Macedonian has borrowed mostly from Serbian and has used the wealth of its dialects.

See also

References

- Balkan Syntax and Semantics, John Benjamins Publishing, 2004, ISBN 158811502X, The typology of Balkan evidentiality and areal linguistic, Victor Friedman, p. 123.

- Цонев, Р. 2008: Говорът на град Банско. Благоевград: Унив. изд. Неофит Рилски, 375 с. Заключение + образци; ISBN 978-954-9438-04-8

- Simeon Radev. Македония и Българското възраждане, Том I и II (Macedonia and the Bulgarian Revival), Издателство „Захарий Стоянов“, Фондация ВМРО, Sofia, 2013, pp. 119

- When Blaze Koneski, the founder of the Macedonian standard language, as a young boy, returned to his Macedonian native village from the Serbian town where he went to school, he was ridiculed for his Serbianized language.Cornelis H. van Schooneveld, Linguarum: Series maior, Issue 20, Mouton., 1966, p. 295.

- ...However this was not at all the case, as Koneski himself testifies. The use of the schwa is one of the most important points of dispute not only between Bulgarians and Macedonians, but also between Macedonians themselves – there are circles in Macedonia who in the beginning of the 1990s denounced its exclusion from the standard language as a hostile act of violent serbianization... For more see: Alexandra Ioannidou (Athens, Jena) Koneski, his successors and the peculiar narrative of a “late standardization” in the Balkans. in Romanica et Balcanica: Wolfgang Dahmen zum 65. Geburtstag, Volume 7 of Jenaer Beiträge zur Romanistik with Thede Kahl, Johannes Kramer and Elton Prifti as ed., Akademische Verlagsgemeinschaft München AVM, 2015, ISBN 3954770369, pp. 367–375.

- Kronsteiner, Otto, Zerfall Jugoslawiens und die Zukunft der makedonischen Literatursprache : Der späte Fall von Glottotomie? in: Die slawischen Sprachen (1992) 29, 142–171.

- Victor Friedman, The Typology of Balkan Evidentiality and Areal Linguistics; Olga Mieska Tomic, Aida Martinovic-Zic as ed. Balkan Syntax and Semantics; vol. 67 от Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today Series; John Benjamins Publishing, 2004; ISBN 158811502X; p. 123.

- Jouko Lindstedt, Conflicting Nationalist Discourses in the Balkan Slavic Language Area in The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders with editors: Tomasz Kamusella, Motoki Nomachi and Catherine Gibson; Palgrave Macmillan; 2016; ISBN 978-1-137-34838-8; pp. 429–447.

- Olga Miseska Tomic, Variation in Clitic-doubling in South Slavic in Article in Syntax and Semantics 36: 443–468; January 2008; doi:10.1163/9781848550216_018.

- Jouko Lindstedt, Balkan Slavic and Balkan Romance: from congruence to convergence in Besters-Dilger, Juliane & al. (eds.). 2014. Congruence in Contact-induced Language Change. Berlin – Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 3110373017; pp. 168–183.

- Motoki Nomachi, “East” and “West” as Seen in the Structure of Serbian: Language Contact and Its Consequences; p. 34. in Slavic Eurasian Studies edited by Ljudmila Popović and Motoki Nomachi; 2015, No.28.

- Friedman V A (2006), Balkans as a Linguistic Area. In: Keith Brown, (Editor-in Chief) Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Second Edition, volume 1, pp. 657–672. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Drezov, Kyril (1999). "Macedonian identity: An overview of the major claims". In Pettifer, James (ed.). The New Macedonian Question. MacMillan Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780230535794.

- Roland Sussex, Paul Cubberley, The Slavic Languages, Cambridge Language Surveys, Cambridge University Press, 2006; ISBN 1139457284, p. 510.

- Ivic, Pavle, Balkan Slavic Migrations in the Light of South Slavic Dialectology in Aspects of the Balkans. Continuity and change with H. Birnbaum and S. Vryonis (eds.) Walter de Gruyter, 2018; ISBN 311088593X, pp. 66–86.

- Lindstedt, Jouko (2016). "Conflicting Nationalist Discourses in the Balkan Slavic Language Area". The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders: 429–447. doi:10.1007/978-1-137-34839-5_21. ISBN 978-1-349-57703-3.

- Tomasz Kamusella, Motoki Nomachi, Catherine Gibson as ed., The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders, Springer, 2016; ISBN 1137348399, p. 434.

- Mladenov, Stefan (1914). "К вопросу о границе между болгарским и сербским языком" [On the Border of the Bulgarian and the Serbian language]. Русский филологический вестник (72): 383–408.

- Misirkov, Krste (September 1898). "Значение на Моравското или ресавското наречие, за съвременната и историческата етнография на Балканския полуостров" [The Significance of the Morava or Resava Dialect to the Modern and Historical Ethnography of the Balkan Peninsula]. Български преглед. Sofia. V: 121–127.

- Tsonev, Benyo (1916). "Научно пътешествие в Поморавието и Македония" [Scientific Exploration of the Pomoravlje and Macedonia]. Научна експедиция в Македония и Поморавието, 1916 г.: 153–154.

- Стойков (Stoykov), Стойко (2002) [1962]. Българска диалектология [Bulgarian Dialectology] (in Bulgarian). София: Акад. изд. "Проф. Марин Дринов". pp. 163–164. ISBN 954-430-846-6. OCLC 53429452.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (1995). Conflict and Chaos in Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 143. ISBN 0312121164.

The obviously plagiarized historical argument of the Macedonian nationalists for a separate Macedonian ethnicity could be supported only by linguistic reality, and that worked against them until the 1940s. Until a modern Macedonian literary language was mandated by the communist-led partisan movement from Macedonia in 1944, most outside observers and linguists agreed with the Bulgarians in considering the vernacular spoken by the Macedonian Slavs as a western dialect of Bulgarian

- Shklifov, Blagoy; Shklifova, Ekaterina (2003). Български деалектни текстове от Егейска Македония [Bulgarian dialect texts from Aegean Macedonia] (in Bulgarian). Sofia. pp. 28–36.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ammon, Ulrich; de Gruyter, Walter (2005). Sociolinguistics: an international handbook of the science of language and society. p. 154. ISBN 3-11-017148-1. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- Chambers, Jack; Trudgill, Peter (1998). Dialectology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 7.

Similarly, Bulgarian politicians often argue that Macedonian is simply a dialect of Bulgarian – which is really a way of saying, of course, that they feel Macedonia ought to be part of Bulgaria. From a purely linguistic point of view, however, such arguments are not resolvable, since dialect continua admit of more-or-less but not either-or judgements.

- Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press, p.259.

- Lindstedt, Jouko (2016). "Conflicting Nationalist Discourses in the Balkan Slavic Language Area". The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders: 429–447. doi:10.1007/978-1-137-34839-5_21. ISBN 978-1-349-57703-3.

- Tomasz Kamusella, Motoki Nomachi, Catherine Gibson as ed., The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders, Springer, 2016; ISBN 1137348399, p. 436.

- Lindstedt, Jouko (2016). "Conflicting Nationalist Discourses in the Balkan Slavic Language Area". The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders: 429–447. doi:10.1007/978-1-137-34839-5_21. ISBN 978-1-349-57703-3.

- Boeschoten, Riki van (1993): Minority Languages in Northern Greece. Study Visit to Florina, Aridea, (Report to the European Commission, Brussels) "The Western dialect is used in Florina and Kastoria and is closest to the language used north of the border, the Eastern dialect is used in the areas of Serres and Drama and is closest to Bulgarian, the Central dialect is used in the area between Edessa and Salonica and forms an intermediate dialect"

- Ioannidou, Alexandra (1999). "Questions on the Slavic Dialects of Greek Macedonia". Ars Philologica: Festschrift für Baldur Panzer zum 65. Geburstag. Karsten Grünberg, Wilfried Potthoff. Athens: Peterlang: 59, 63. ISBN 9783631350652.

In September 1993 ... the European Commission financed and published an interesting report by Riki van Boeschoten on the "Minority Languages in Northern Greece", in which the existence of a "Macedonian language" in Greece is mentioned. The description of this language is simplistic and by no means reflective of any kind of linguistic reality; instead it reflects the wish to divide up the dialects comprehensibly into geographical (i.e. political) areas. According to this report, Greek Slavophones speak the "Macedonian" language, which belongs to the "Bulgaro-Macedonian" group and is divided into three main dialects (Western, Central and Eastern) - a theory which lacks a factual basis.

- The Slavic Languages, Roland Sussex, Paul Cubberley, Publisher Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 1139457284, p. 42.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 1-4039-6417-3

- Lunt, Horace G. (2001). Old Church Slavonic Grammar (7th ed.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; p.1; ISBN 978-3-110-16284-4.

- Ivo Banac, The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics, Cornell University Press, 1988, ISBN 0801494931, p. 47.

- Wahlström, Max. 2015. The loss of case inflection in Bulgarian and Macedonian (Slavica Helsingiensia 47); University of Helsinki, ISBN 9789515111852.

- John Van Antwerp Fine, The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, 1994, ISBN 0472082604, p. 355.

- Detrez, Raymond; Segaert, Barbara; Lang, Peter (2008). Europe and the Historical Legacies in the Balkans. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-90-5201-374-9. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Bechev, Dimitar (2009-04-13). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia Historical Dictionaries of Europe. Scarecrow Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8108-6295-1. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- From Rum Millet to Greek and Bulgarian Nations: Religious and National Debates in the Borderlands of the Ottoman Empire, 1870–1913. Theodora Dragostinova, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH.

- "Венедиктов Г. К. Болгарский литературный язык эпохи Возрождения. Проблемы нормализации и выбора диалектной основы. Отв. ред. Л. Н. Смирнов. М.: "Наука"" (PDF). 1990. pp. 163–170. (Rus.). Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Ц. Билярски, Из българския възрожденски печат от 70-те години на XIX в. за македонския въпрос, сп. "Македонски преглед", г. XXIII, София, 2009, кн. 4, с. 103–120.

- Neofit Rilski, Bulgarian Grammar in Late Enlightenment: Emergence of the Modern 'National Idea', Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945) with editors Balázs Trencsényi and Michal Kopeček, Central European University Press, 2006, ISBN 6155053847, pp. 246–251

- Makedoniya July 31st 1870

- Tchavdar Marinov. In Defense of the Native Tongue: The Standardization of the Macedonian Language and the Bulgarian-Macedonian Linguistic Controversies. in Entangled Histories of the Balkans – Volume One. doi:10.1163/9789004250765_010 p. 443

- Благой Шклифов, За разширението на диалектната основа на българския книжовен език и неговото обновление. "Македонската" азбука и книжовна норма са нелегитимни, дружество "Огнище", София, 2003 г. . стр. 7–10.

- Благой Шклифов, За разширението на диалектната основа на българския книжовен език и неговото обновление. "Македонската" азбука и книжовна норма са нелегитимни, дружество "Огнище", София, 2003 г. . стр. 9.

- https://www.strumski.com/books/Josif_Kovachev_za_Obshtia_Bulgarski_Ezik.pdf

- Stoykov, Stoyko Stoykov (1962). Bulgarian dialectology. Sofia: Prof. Marin Drinov University Press. pp. 185, 186, 187.

- Schmieger, R. 1998. "The Situation of the Macedonian Language in Greece: Sociolinguistic Analysis", International Journal of the Sociology of Language 131, 125–55.

- Clyne, Michael G., ed. (1992). Pluricentric languages: differing norms in different nations. Walter de Gruyter & Co. p. 440. ISBN 3110128551. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- "Macedonian Language and Nationalism During the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries", Victor Friedman, p. 286

- Nationalism, Globalization, and Orthodoxy: The Social Origins of Ethnic Conflict in the Balkans, p. 145, at Google Books, Victor Roudometof, Roland Robertson, p. 145

- "Though Loza adhered to the Bulgarian position on the issue of the Macedonian Slavs' ethnicity, it also favored revising the Bulgarian orthography by bringing it closer to the dialects spoken in Macedonia." Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0-8108-6295-6, p. 241.

- The Young Macedonian Literary Association's Journal, Loza, was also categorical about the Bulgarian character of Macedonia: "A mere comparison of those ethnographic features which characterize the Macedonians (we understand: Macedonian Bulgarians), with those which characterize the free Bulgarians, their juxtaposition with those principles for nationality which we have formulated above, is enough to prove and to convince everybody that the nationality of the Macedonians cannot be anything except Bulgarian." Freedom or Death, The Life of Gotsé Delchev, Mercia MacDermott, The Journeyman Press, London & West Nyack, 1978, p. 86.

- "Macedonian historiography often refers to the group of young activists who founded in Sofia an association called the ‘Young Macedonian Literary Society’. In 1892, the latter began publishing the review Loza [The Vine], which promoted certain characteristics of Macedonian dialects. At the same time, the activists, called ‘Lozars’ after the name of their review, ‘purified’ the Bulgarian orthography from some rudiments of the Church Slavonic. They expressed likewise a kind of Macedonian patriotism attested already by the first issue of the review: its materials greatly emphasized identification with Macedonia as a genuine ‘fatherland’. In any case, it is hardly surprising that the Lozars demonstrated both Bulgarian and Macedonian loyalty: what is more interesting is namely the fact that their Bulgarian nationalism was somehow harmonized with a Macedonian self-identification that was not only a political one but also demonstrated certain ‘cultural’ contents. "We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe", Diana Miškova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 963-97762-8-9, p. 120.

- Banač, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 317. ISBN 0-8014-9493-1. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Fisiak, Jacek (1985). Papers from the Sixth International Conference on Historical Linguistics, v. 34. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 13–14. ISBN 90-272-3528-7. ISSN 0304-0763. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Fishman, Joshua A.; de Gruyter, Walter (1993). The Earliest Stage of Language Planning: The "First Congress" Phenomenon. pp. 161–162. ISBN 3-11-013530-2. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Danforth, Loring M. (1995). The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world. Princeton University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-691-04356-6. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (1995-03-15). Conflict and Chaos in Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 143. ISBN 0-312-12116-4. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Busch, Birgitta; Kelly-Holmes, Helen (2004). Language, discourse and borders in the Yugoslav successor states – Current issues in language and society monographs, Birgitta Busch, Helen Kelly-Holmes, Multilingual Matters. pp. 24–25. ISBN 1-85359-732-5. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- "Up until the early 20th century and beyond, the international community viewed Macedonians as a regional variety of Bulgarians, i.e. Western Bulgarians." Nationalism and Territory: Constructing Group Identity in Southeastern Europe, Geographical perspectives on the human past : Europe: Current Events, George W. White, Rowman & Littlefield, 2000 at Google Books, ISBN 0-8476-9809-2.

- "At the end of the WWI there were very few historians or ethnographers, who claimed that a separate Macedonian nation existed... Of those Slavs who had developed some sense of national identity, the majority probably considered themselves Bulgarians, although they were aware of differences between themselves and the inhabitants of Bulgaria... The question as of whether a Macedonian nation actually existed in the 1940s when a Communist Yugoslavia decided to recognize one is difficult to answer. Some observers argue that even at this time it was doubtful whether the Slavs from Macedonia considered themselves a nationality separate from the Bulgarians." The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world, Loring M. Danforth, Princeton University Press, 1997, p. 66, at Google Books, ISBN 0-691-04356-6

- "During the 20th century, Slavo-Macedonian national feeling has shifted. At the beginning of the 20th century, Slavic patriots in Macedonia felt a strong attachment to Macedonia as a multi-ethnic homeland. They imagined a Macedonian community uniting themselves with non-Slavic Macedonians... Most of these Macedonian Slavs also saw themselves as Bulgarians. By the middle of the 20th. century, however Macedonian patriots began to see Macedonian and Bulgarian loyalties as mutually exclusive. Regional Macedonian nationalism had become ethnic Macedonian nationalism... This transformation shows that the content of collective loyalties can shift." Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe, Ethnologia Balkanica Series, Klaus Roth, Ulf Brunnbauer, LIT Verlag Münster, 2010, p. 147, at Google Books, ISBN 3-8258-1387-8.

- Performing Democracy: Bulgarian Music and Musicians in Transition, Donna A. Buchanan, University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 260, at Google Books, ISBN 0-226-07827-2.

- Kortmann, Bernd; van der Auwera, Johan; de Gruyter, Walter (2011-07-27). The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide. p. 515. ISBN 978-3-11-022026-1. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Ammon, Ulrich; de Gruyter, Walter (2005). Sociolinguistics: an international handbook of the science of language and society. p. 154. ISBN 3-11-017148-1. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Trudgill, Peter (1992), "Ausbau sociolinguistics and the perception of language status in contemporary Europe", International Journal of Applied Linguistics 2 (2): 167–177

- The Slavic Languages, Roland Sussex, Paul Cubberley. Cambridge University Press. 2006-09-21. p. 71. ISBN 1-139-45728-4. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- The Changing Scene in World Languages: Issues and Challenges, Marian B. Labrum. John Benjamins Publishing. 1997. p. 66. ISBN 90-272-3184-2. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- Fishman, Joshua. "Languages late to literacy: finding a place in the sun on a crowded beach". In: Joseph, Brian D. et al. (ed.), When Languages Collide: Perspectives on Language Conflict, Competition and Coexistence; Ohio State University Press (2002), pp. 107–108.

- Mirjana N. Dedaić, Mirjana Misković-Luković. South Slavic discourse particles (John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2010), p. 13

- Victor Roudometof. Collective memory, national identity, and ethnic conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian question (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002), p. 41

- Language profile Macedonian Archived 2009-03-11 at the Wayback Machine, UCLA International Institute

- G. Lunt, Horace (1952). A Grammar of the Macedonian Literary Language. Skopje. p. 21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stoykov, Stoyko Stoykov (1962). Bulgarian dialectology. Sofia: Prof. Marin Drinov University Press. pp. 172, 181, 183.

- Friedman (2001), p. 10.

- Stoykov, Stoyko Stoykov (1962). Bulgarian dialectology. Sofia: Prof. Marin Drinov University Press. pp. 148–159, 169–170, 176–179.

- "Български диалектен атлас. Обобщаващ том. I-III. Фонетика. Акцентология. Лексиология" [Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects.Generalizing Volume. I-III. Phonetics. Accentology. Lexicology]. Sofia: Trud. 2001. p. 58.

- "Български диалектен атлас. Обобщаващ том. I-III. Фонетика. Акцентология. Лексиология" [Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects.Generalizing Volume. I-III. Phonetics. Accentology. Lexicology]. Sofia: Trud. 2001. p. 77.

- Кочев (Kochev), Иван (Ivan) (2001). Български диалектен атлас (Bulgarian dialect atlas) (in Bulgarian). София: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 954-90344-1-0. OCLC 48368312.

- "Български диалектен атлас. Обобщаващ том. I-III. Фонетика. Акцентология. Лексиология" [Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects.Generalizing Volume. I-III. Phonetics. Accentology. Lexicology]. Sofia: Trud. 2001. p. 191.

- "Български диалектен атлас. Обобщаващ том. I-III. Фонетика. Акцентология. Лексиология" [Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects.Generalizing Volume. I-III. Phonetics. Accentology. Lexicology]. Sofia: Trud. 2001. p. 194.

- Tsoneva, Dimitrina. "Отново за палаталността на българските съгласни" [Again on the Palatalisation of Consonants in Bulgarian] (PDF) (in Bulgarian). pp. 1–6.

- Choi, Gwon-Jin. "Фонологичността на признака мекост в съвременния български език" [The Phonological Value of the Feature [Palatalness] in Contemporary Bulgarian].

- "Български диалектен атлас. Обобщаващ том. IV. Морфология" [Atlas of Bulgarian Dialects.Generalizing Volume. IV. Morphology]. Sofia: Prof. Marin Drinov Publishing House of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. 2016. p. 79.

- Stancheva, Ruska (2017). "За кодификацията на правилото за пълен и кратък член" [On the Codification of the Long and Short Article in Modern Bulgarian] (PDF).

- http://christotamarin.blogspot.com/2016/10/BulgarianLongShortArticle.html#ProblemDefinition-3

- G. Lunt, Horace (1952). A Grammar of the Macedonian Literary Language. Skopje. p. 31.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - G. Lunt, Horace (1952). A Grammar of the Macedonian Literary Language. Skopje. p. 99.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schick, Ivanka; Beukema, Frits (2001). "Clitic doubling in Bulgarian". Linguistics in the Netherlands. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Filkova, Penka (1986), Староболгаризмы и церковнославянизмы в лексике русского литературного языка [Old Bulgarianisms and Church Slavonisms in the Russian Literary Language], vol. 1, Sofia

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Filkova, Penka (1986), Староболгаризмы и церковнославянизмы в лексике русского литературного языка [Old Bulgarianisms and Church Slavonisms in the Russian Literary Language], vol. 2, Sofia

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Filkova, Penka (1986), Староболгаризмы и церковнославянизмы в лексике русского литературного языка [Old Bulgarianisms and Church Slavonisms in the Russian Literary Language], vol. 3, Sofia

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Filkova, Penka (1986), Староболгаризмы и церковнославянизмы в лексике русского литературного языка [Old Bulgarianisms and Church Slavonisms in the Russian Literary Language], vol. 1, Sofia, pp. 47–50

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Bibliography

- Friedman, Victor (2001), Macedonian, SEELRC