Baladine Klossowska

Baladine Klossowska or Kłossowska (21 October 1886 – 11 September 1969) was a German painter. Originating from an artistic Jewish family with roots in Lithuania, she moved from Breslau, Germany, to Paris, France, at the turn of the 20th century, where she was a vivid and active participant in the explosion of artistic experiment then active in the city.

Baladine Klossowska | |

|---|---|

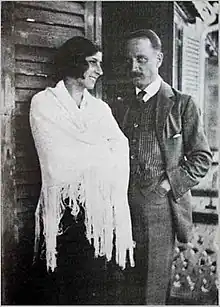

Klossowska (with Rilke) c. 1923 | |

| Born | Elisabeth Dorothea Spiro 21 October 1886 |

| Died | 21 October 1969 (aged 83) |

| Spouse | |

| Partner(s) | Rainer Maria Rilke (1919–1926, his death) |

| Children |

|

She was mother to controversial modernist painter Balthus[1] as well as the writer Pierre Klossowski,[2] and the final muse and love of the poet Rainer Maria Rilke.[3]

Biography

Early life

Born Elisabeth Dorothea Spiro in Breslau, Germany (now Polish Wrocław), to a Jewish family. Her father, Abraham Baer Spiro (Shapiro), was a Lithuanian Jewish cantor, who moved his family from Korelichi in Novogrudok district of Minsk Governorate to Breslau in 1873.[4][5][6] In Breslau, he was appointed a Chief cantor of the White Stork Synagogue – one of the two main synagogues of the city.[7][8][9] The Spiros were an artistically inclined family. Balandine's older brother Eugene Spiro became an artist-painter.

Move to Paris

Spiro married the painter and art historian Erich Klossowski in 1902. The couple left Breslau the same year, and were settled in Paris by 1903.[10] Their sons, Pierre (1905) and Balthasar (1908) were born in this new city.

Spiro embraced Paris with a new identity, becoming Baladine Klossowska (out of Balladyna, the heroine of Juliusz Słowacki's romantic drama).[11] Like many women in intellectual and artistic circles in Paris in the first decade of the new century, although preoccupied with tasks of household and home, Klossowska continued painting, if episodically.

Displacement of WWI

The Klossowskis were forced to leave France in 1914, at the start of World War I, due to their German citizenship. The couple separated permanently in 1917, and Klossowska took her sons to Switzerland. They moved to Berlin in 1921 due to financial pressures.[12] Mother and sons returned to Paris in 1924, where the three for a time lived a materially marginal existence, often dependent upon help from friends and relations, until Pierre and Balthus became established professionally. Balthus, who became rich off of his paintings, later said of these times "'I was poor. The only option was to make a scandal. It worked well. Too well.'"[13]

With Rilke in Switzerland

Klossowska met Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) in 1919. They had previously known of each other in Paris, but had not been more than acquaintances. Rilke, eleven years Klossowska's senior, had during those Paris years socialized with an older generation of artists and intellectuals, while Klossowska and Erich had been young (if well-connected) upcomers.

In 1919, Rilke was emerging from a severe depression that had limited his writing to uncollected poems and a large number of letters, both during and after World War I. Klossowska has been described as both "inspiring" Rilke in his late poetry, and "suffering emotionally in his hands."[14] The two had an intense, episodic romantic relationship that lasted until Rilke's death from leukemia in 1926.

Klossowska helped Rilke establish his residence in Muzot, Switzerland, finding and directing the renovations for him of the Château de Muzot. Her sons developed close relationships with Rilke, and Balthasar—the future Balthus—published his first book of watercolors about a lost cat, Mitsou, with text by Rilke, during this period.

In 1922, Rilke wrote, in what he called "a savage creative storm," his two most important collections of poetry, the Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus, both published in 1923. Klossowska, who gave Rilke a Christmas gift of Ovid's Metamorphisis in 1920 (a French translation which included the episodes of the Orpheus cycle) and a postcard image of Orpheus, is generally understood to have crystallized the ideas that enabled him to see this cycle in a form appropriate to his poetic voice.[14]

During their romance, Rilke called Klossowska by the pet name "Merline" (a female "Merlin," or "sorceress") in their correspondence—first published in 1954.[15][16] Rilke fans are divided in their opinions as to whether she was a positive force, or a negative force, on his life and writing, and Klossowska's reputation has been largely defined by whether or not Rilke's critics found her influence sympathetic.

Final years in France

Klossowska lived in Paris at 69 rue de la Glacière in her final years. She died at the home of her son Pierre, in Bagneux, Hauts-de-Seine.[17]

References

- Jean Clair, Balthus, London, Thames & Hudson, 2001.

- Anthony Spira and Sarah Wilson, Pierre Klossowski, Ostfildern, Germany, Hatje Cantz, 2006.

- Ralph Freedman, Life of a Poet: Rainer Maria Rilke, Evanston, IL, Northwestern University Press, 1998.

- "Balthus | French painter".

- Charles A. Riley, Aristocracy and the Modern Imagination (p. 207)

- Sabine Rewald, Balthus (p.11)

- Marmor, Prunk und große Namen

- Peter Spiro «Erinnerungen»

- Stary Cmentarz Żydowski we Wrocławiu Archived 15 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Rewald, Sabine (8 October 2013). Balthus: Cats and Girls. Yale University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-300-19701-3.

- "Baladine Klossowska", Wikipedia, wolna encyklopedia (in Polish), 1 February 2022, retrieved 5 May 2022

- Edward Lucie-Smith, Lives of the Great Twentieth Century Artists, New York, Rizzoli, 1986; p. 299.

- Glass, Nicholas (25 April 2000). "'I was poor. The only option was to make a scandal. It worked well. Too well'". the Guardian. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- Eldridge, Hannah Vandegrift; Fischer, Luke (10 May 2019). Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus: Philosophical and Critical Perspectives. Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-19-068544-7.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Baladine Klossowska, Correspondence 1920–1926, Zurich, 1954.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to Merline, 1919–1922, St. Paul, MN, Paragon House, 1989.

- "Baladine Klossowska", Wikipédia (in French), 12 February 2021, retrieved 5 May 2022