Bairagi Brahmin (caste)

Bairagi Brahmin is a Hindu caste. They are also called by different names that are Swami, Bairagi, Mahant, Vaishnav, Vairagi, Ramanandi, Shami, Vaishnav, Pujari. They are Vaishnav, and wear the sacred thread. A majority of Bairagi Brahmin is found in West Bengal, Assam, Odisha, Bihar and the eastern parts of Uttar Pradesh. Bairagi are considered as part of the upper castes of Bengal – Brahmin, Rajput, Chatri, Grahacarya and Baidya.[2]

| Bairagi | |

|---|---|

| Swami • Vaishnav • Mahant | |

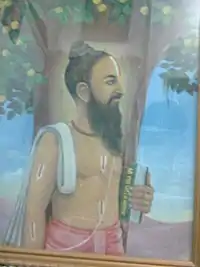

A Portrait of Bairagi Mahant (Tilak of Ramanandi Sampradaya on his body) | |

| Classification | Ramanandi Sampradaya • Nimbarka Sampradaya • Vishnuswami Sampradaya • Madhvacharya Sampradaya[1] |

| Kuladevta (male) | Rama • Krishna • (Avatars of Vishnu) • Hanuman |

| Kuladevi (female) | Sita • Radha• Tulsi • (Avtars of Lakshmi) |

| Guru | Ramananda • Tulsidas • Ramanuja |

| Nishan | Kapidhwaj (Hanuman on Flag) |

| Religions | |

| Languages | Hindi • Awadhi • Bhojpuri • Braj Bhasha • Maithili • Magahi • Angika • Bajjika • Nagpuri • Bagheli • Bundeli • Kannauji • Kauravi • Haryanvi • Bagri• Punjabi • Rajasthani • Gujarati • Chhattisgarhi • Odia • Bengali • Marathi |

| Country | India • Nepal |

| Populated states | India Uttar Pradesh • Bihar • Jharkhand • Madhya Pradesh • Himachal Pradesh • Uttarakhand • Rajasthan • Punjab • Maharastra • Gujarat • Chhattisgarh • Odisha • West Bengal • Haryana Nepal Madhesh |

| Feudal title | Mahant/Swami/Bawa |

| Color | Bhagwa or White |

| Historical grouping | Brahmin • |

| Status | Monasterial Community |

Bairagi Brahmin belong to the Brahmin varna. Senugupta describes them as a High caste group.[3] William Pinch believes that the Bairagi branch of Vaishnavas is the result of the Galta conference of 17th Century.[4]

Bairagi brahmin caste is formed of Brahmins and Kshatriya. In 1713 a meeting was held of all Vaishnava (Bairagis) in Galta Temple and it was decided that only Brahmins and Kshatriya would be part of bairagis. And they excluded other castes.[5] In 1720, Maharaja Jai Singh II, king of Jaipur State held a meeting with all vaishnava mahants and was decided that other castes would not be part of bairagis. Maharaja Jai Singh II obtained pledges from Ramanandi mahants and other vaishnava to maintain strict caste rules.[6]

According to Mayer, the Bairagis were one of a few sectarian castes which accepted admissions from higher castes. He states that they Bairagis had a worldly and celibate branches of the caste. He states they were considered of equal status with Brahmins, Rajputs, and Jats.[7]

Structure

Bairagis brahmins are divided into four Sampradayas - often referred to collectively as the 'Chatur-Sampradaya'. 1. Rudra Sampradaya (Vishnuswami), 2. Sri Sampradaya (Ramanandi), 3. Nimbarka Sampradaya and 4. Brahma Sampradaya (Madhvacharya).[8]

Dynasties

Nandgaon

The first ruler Mahant Ghasi Das of Nandgaon State, was recognized as a feudal chief by the British government in 1865 and was granted a sanad of adoption. Later the British conferred the title of raja on the ruling mahant.[9][10]

Chhuikhadan

The chiefs of Chhuikhadan State were originally under the Bhonsles of Nagpur, the first Chief being Mahant Rup Das in 1750. However, after defeat of Marathas, they were recognized by British as feudatory chiefs in 1865 conferring the title and sanad to Mahant Laxman Das.[11]

Mahabharat

The Mahabharata says that once, after Babruvahana dug a dry pond, a Bairagi Brahmin reached the centre of pond and instantly water came out of the pond with a thunderous noise.[15]

References

- Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- Nirmal Kumar Bose, Some Aspects of Caste in Bengal, p.399, Vol. 71, No. 281, Traditional India: Structure and Change, American Folklore Society

- Senugupta, Parna (2011). Pedagogy for Religion: Missionary Education and the Fashioning of Hindus and Muslims in Bengal. University of California Press. pp. 104, 112.

- Choubey, Devendra. Sahitya Ka Naya Soundaryashastra (in Hindi). Kitabghar Prakashan. p. 282. ISBN 978-81-89859-11-4.

- Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- Mayer, Adrian C. (1960). Caste and Kinship in Central India. Routledge. pp. 28–29. 36–39.

- Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- Chhattisgarh ki Riyaste/Princely stastes aur Jamindariyaa. Raipur: Vaibhav Prakashan. 2011. ISBN 978-81-89244-96-5.

- Chhattisgarh ki Janjaatiyaa/Tribes aur Jatiyaa/Castes. Delhi: Mansi publication. 2011. ISBN 978-81-89559-32-8.

- Princely states of India: a guide to chronology and rulers by David P. Henige - 2004 - Page 48

- [South Asian Religions on Display: Religious Processions in South Asia and in the Diaspora, Knut A. Jacobsen, ISBN hardback 978-0-415-4373-3, ISBN ebook ISBN hardback 978-0-203-93059-5]

- Jāyasavāla, Akhileśa (1991). 18vīṃ śatābdī meṃ Avadha ke samāja evaṃ saṃskr̥ti ke katipaya paksha: śodha prabandha (in Hindi). Śāradā Pustaka Bhavana.

- "बाकी अखाड़ों से अलग कैसे है 'दिगंबर अखाड़ा'?". News18 India. 19 December 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- Makhan Jha (1998), India and Nepal : Sacred Centres and Anthropological Researches, p. 100, ISBN 81-7533-081-3