Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen, BWV 56

Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen (lit. 'I will gladly carry the cross-staff'), BWV 56, is a church cantata composed by Johann Sebastian Bach for the 19th Sunday after Trinity. It was first performed in Leipzig on 27 October 1726. The composition is a solo cantata (German: Solokantate) because, apart from the closing chorale, it requires only a single vocal soloist (in this case a bass). The autograph score is one of a few cases where Bach referred to one of his compositions as a cantata. In English, the work is commonly referred to as the Kreuzstab cantata. Bach composed the cantata in his fourth year as Thomaskantor; it is regarded as part of his third cantata cycle.

| Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen | |

|---|---|

BWV 56 | |

| Church cantata by J. S. Bach | |

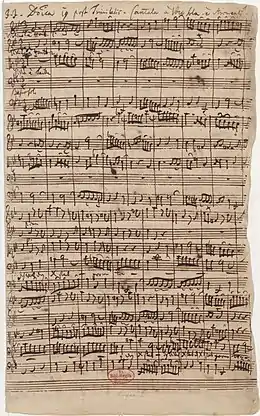

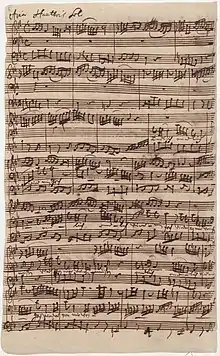

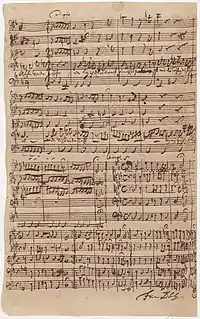

Autograph manuscript of opening bass aria from BWV 56[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Occasion | 19th Sunday after Trinity |

| Cantata text | by Christoph Birkmann |

| Chorale | "Du, o schönes Weltgebäude" by Johann Franck |

| Performed | 27 October 1726: Leipzig |

| Duration | 21 minutes |

| Movements | five |

| Vocal | |

| Instrumental | |

The text was written by Christoph Birkmann, a student of mathematics and theology in Leipzig who collaborated with Bach. He describes in the first person a Christian willing to "carry the cross" as a follower of Jesus. The poet compares life to a voyage towards a harbour, referring indirectly to the prescribed Gospel reading which says that Jesus travelled by boat. The person, at the end, yearns for death as the ultimate destination, to be united with Jesus. This yearning is reinforced by the closing chorale: the stanza "Komm, o Tod, du Schlafes Bruder" ('Come, o death, you brother of sleep') from Johann Franck's 1653 hymn "Du, o schönes Weltgebäude", which uses the imagery of a sea voyage.

Bach structured it in five movements, alternating arias and recitatives for a bass soloist, and closing with a four-part chorale. He scored the work for a Baroque instrumental ensemble of three woodwind instruments, three string instrument parts and continuo. An obbligato cello features in the first recitative and an obbligato oboe in the second aria, resulting in different timbres in the four movements for the same voice part. The autograph score and the performance parts are held by the Berlin State Library. The cantata was published in 1863 in volume 12 of the Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe (BGA). The Neue Bach-Ausgabe (NBA) published the score in 1990. A critical edition was published by Carus-Verlag in 1999.

In his biography of Bach, Albert Schweitzer said the cantata placed "unparalleled demands on the dramatic imagination of the singer," who must "depict convincingly this transition from the resigned expectation of death to the jubilant longing for death."[1] Beginning with a live broadcast in 1939, the cantata has been frequently recorded, with some soloists recording it several times. The closing chorale features in Robert Schneider's 1992 novel, Schlafes Bruder, and its film adaptation, Brother of Sleep.

Background

In 1723, Bach was appointed Thomaskantor (director of church music) of Leipzig. The position gave him responsibility for the music at four churches, and the training and education of boys singing in the Thomanerchor.[2] Cantata music was required for two major churches, Thomaskirche and Nikolaikirche, and simpler church music for two smaller churches, Neue Kirche and Peterskirche.[3][4]

Bach took office on the first Sunday after Trinity, in the middle of the liturgical year. In Leipzig, cantata music was expected on Sundays and feast days except for the "silent periods" (tempus clausum) of Advent and Lent. In his first year, Bach decided to compose new works for almost all liturgical events; these works became known as his first cantata cycle.[5] He continued the following year, composing a cycle of chorale cantatas with each cantata based on a Lutheran hymn.[6]

Third Leipzig cantata cycle

The third cantata cycle encompasses works composed during Bach's third and fourth years in Leipzig, and includes Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen.[7][8] One characteristic of the third cycle is that Bach performed more works by other composers, and repeated his own, earlier works.[8] His new works have no common theme, as the chorale cantatas did.[9] Bach demonstrated a new preference for solo cantatas, dialogue cantatas and cantatas dominated by one instrument (known as concertante cantatas).[9] During the third cycle, he repeated performances of solo cantatas from his Weimar period based on texts by Georg Christian Lehms: Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut, BWV 199, and Widerstehe doch der Sünde, BWV 54. He used more texts by Lehms in the third cycle before turning to other librettists.[9]

Bach's solo cantatas are modelled after secular Italian works by composers such as Alessandro Scarlatti. Like the models, even church cantatas do not contain biblical text and very few close with a chorale.[9] His writing for solo voice is demanding and requires trained singers. Richard D. P. Jones, a musicologist and Bach scholar, assumes that Bach "exploited the vocal technique and the interpretative skills of particular singers".[9] Jones describes some of these solo cantatas, especially Vergnügte Ruh, beliebte Seelenlust, BWV 170; Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen; and Ich habe genug, BWV 82; as among Bach's "best loved" cantatas.[9]

Although dialogue cantatas also appear earlier in Bach's works, all four dialogues between Jesus and the Soul (Anima)—based on elements of the Song of Songs—are part of the third cycle.[10] The only chorale cantata of the third cycle, Lobe den Herren, den mächtigen König der Ehren, BWV 137, follows the omnes versus style and sets all stanzas of a hymn unchanged; Bach rarely used this style in his chorale cantatas, except in the early Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4, and later chorale cantatas.[11]

Occasion, readings and text

.jpg.webp)

Bach wrote the cantata for the 19th Sunday after Trinity, during his fourth year in Leipzig.[12] The prescribed readings for that Sunday were from Paul's epistle to the Ephesians—"Put on the new man, which after God is created" (Ephesians 4:22–28)—and the Gospel of Matthew: healing the paralytic at Capernaum (Matthew 9:1–8).[12] For the occasion, Bach had composed in 1723 Ich elender Mensch, wer wird mich erlösen, BWV 48 (Wretched man that I am, who shall deliver me?),[13] and in 1724 the chorale cantata Wo soll ich fliehen hin, BWV 5 (Where shall I flee), based on Johann Heermann's penitential hymn of the same name.[14]

Poet, theme and text

Until 2015 the librettist was unknown (as for most of Bach's Leipzig cantatas), but in that year researcher Christine Blanken from the Bach Archive[15] published findings suggesting that Christoph Birkmann wrote the text of Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen.[16] Birkmann was a student of mathematics and theology at the University of Leipzig from 1724 to 1727. During that time, he also studied with Bach and appeared in cantata performances.[17] He published a yearbook of cantata texts in 1728, Gott-geheiligte Sabbaths-Zehnden (Sabbath Tithes Devoted to God), which contains several Bach cantatas—including Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen.[18][19] Birkmann has been generally accepted as the author of this cantata.[20]

.jpg.webp)

The librettist built on Erdmann Neumeister's text from "Ich will den Kreuzweg gerne gehen", which was published in 1711.[12] Kreuzweg, the Way of the Cross, refers to the Stations of the Cross and more generally to the "cross as the burden of any Christian".[21] Here Kreuzweg is replaced with Kreuzstab, which can refer to both a pilgrim's staff (or bishop's crosier) and a navigational instrument known as a cross staff or Jacob's staff.[22] Birkmann had an interest in astronomy and knew the second meaning from his studies.[23] In the cantata's text, life is compared to a pilgrimage and a sea voyage.[24]

Birkmann's text alludes to Matthew's gospel; although there is no explicit reference to the sick man, he speaks in the first person as a follower of Christ who bears his cross and suffers until the end, when (in the words of Revelation 7:17) "God shall wipe away the tears from their eyes". The cantata takes as its starting point the torments that the faithful must endure.[12]

The text is also rich in other biblical references. The metaphor of life as a sea voyage in the first recitative comes from the beginning of that Sunday's Gospel reading: "There He went on board a ship and passed over and came into His own city" (Matthew 9:1).[24] Affirmations that God will not forsake the faithful on this journey and will lead them out of tribulation were taken from Hebrews 13:5 and Revelation 7:14.[12]

The third movement expresses joy at being united with the saviour, and its text refers to Isaiah 40:31: "Those that wait upon the Lord shall gain new strength so that they mount up with wings like an eagle, so that they run and do not grow weary".[12] The theme of joy, coupled with a yearning for death, runs through the cantata.[12]

The final lines of the opening aria ("There my Saviour himself will wipe away my tears") are repeated just before the closing chorale. This uncommon stylistic device appears several times in Bach's third cantata cycle.[12]

On the title page, Bach replaced the word "Kreuz" with the Greek letter χ, a rebus he used to symbolize the paradox of the cross.[25]

Chorale

The final chorale is a setting of the sixth stanza of Johann Franck's "Du, o schönes Weltgebäude",[20] which contains ship imagery: "Löse meines Schiffleins Ruder, bringe mich an sichern Port" ("Release the rudder of my little ship, bring me to the secure harbour").[26] The hymn was published in 1653 with a 1649 melody by Johann Crüger. Its text describes (in the first person) renouncing the beautiful dwelling place of the world ("schönes Weltgebäude"), only longing so dearly for the most cherished Jesus ("allerschönstes Jesulein").[27] This phrase recurs, with slight variations, at the end of each stanza.[27]

First performance

Bach conducted the cantata's first performance on 27 October 1726.[20] The soloist may have been Johann Christoph Samuel Lipsius.[28] The performance followed another of his solo cantatas the previous Sunday, Gott soll allein mein Herze haben, BWV 169, which also, unusually for a solo cantata, ends with a chorale.[29]

Music

Structure and scoring

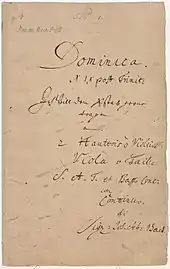

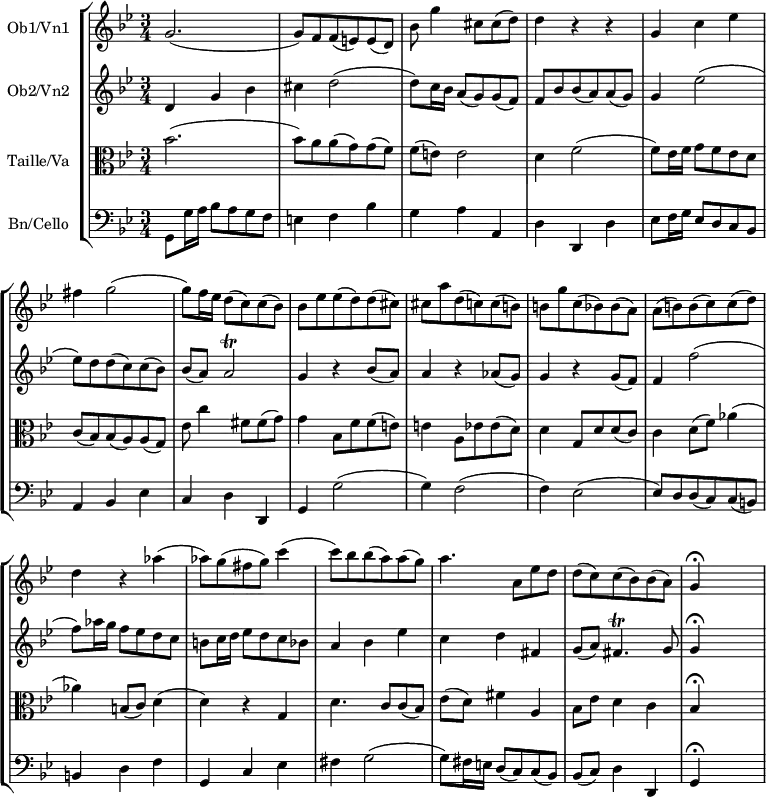

The cantata is structured in five movements, with alternating arias, recitatives and a four-part chorale. Bach scored for a bass soloist, a four-part choir (SATB) in the closing chorale, and a Baroque instrumental ensemble of two oboes (Ob), taille (Ot), two violins (Vl), viola (Va), cello (Vc), and basso continuo.[20] Except for the obbligato oboe in the third movement, the three oboes double the violins and viola colla parte. The title page of the autograph score reads: "Domin. 19 post Trinit. / Ich will den Xstab gerne tragen / a / 2 / Hautb. o Viol. / Viola o / Taille / 4 Voci / Basso solo / e / Cont. / di / J.S.Bach". The score begins with the line "J.J.Dominica 19 post trinitatis. Cantata à Voce sola. è stromenti"[30] ("J.J. Sunday 19 after Trinity, Cantata for solo voice, and instruments"), making it one of the few works Bach termed a cantata.[12] It is 21 minutes long.[31]

In the following table, the scoring follows the Neue Bach-Ausgabe (New Bach Edition). The keys and time signatures are from Alfred Dürr, and use the symbol for common time.[32] The continuo, played throughout, is not shown.

| No. | Title | Text | Type | Vocal | Winds | Strings | Key | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen | Birkmann | Aria | Bass | 2Ob Ot | 2Vl Va | G minor | 3 4 |

| 2 | Mein Wandel auf der Welt / ist einer Schiffahrt gleich | Birkmann | Recitative | Bass | Vc | B-flat major | ||

| 3 | Endlich, endlich wird mein Joch / wieder von mir weichen müssen | Birkmann | Aria | Bass | Ob | B-flat major | ||

| 4 | Ich stehe fertig und bereit | Birkmann | Recitative | Bass | 2Vl Va | G minor | ||

| 5 | Komm, o Tod, du Schlafes Bruder | Franck | Chorale | SATB | 2Ob Ot | 2Vl Va | C minor |

Movements

Musicologist and Bach scholar Christoph Wolff wrote that Bach achieves "a finely shaded series of timbres" in Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen.[33] The four solo movements are scored differently: all instruments accompany the opening aria; only the continuo is scored for the secco recitative, an obbligato oboe adds colour to the central aria, and strings intensify for the accompagnato recitative. All instruments return for the closing chorale.[34]

In his biography of Bach, Albert Schweitzer points out that Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen is among the few works in which Bach carefully marked the phrasing of the parts; others are the Brandenburg Concertos, the St Matthew Passion, the Christmas Oratorio and a few other cantatas, including Ich habe genug and O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort, BWV 60.[35]

1

| External audio | |

|---|---|

The opening aria begins with "Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen, er kömmt von Gottes lieber Hand" ("I will my cross-staff gladly carry, it comes from God's beloved hand."[36]).[21]

The German text with Henry Drinker's English translation reads:

Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen, |

I will my cross-staff gladly carry; |

It is in bar form (AAB pattern), with two stollen (A) followed by an abgesang (B). The first stollen begins with a ritornello for full orchestra—with the theme initially heard in the second oboe and violin parts—anticipating in counterpoint the rising and falling motif of the bass soloist. An augmented second C♯ emphasises the word Kreuzstab, followed by descending sighing figures symbolizing the bearing of the cross.[37]

John Eliot Gardiner, who conducted the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage in 2000, described the beginning of the bass melody as a musical rebus, or conjunction of two words, Kreuz-stab, with the upward part "a harrowing arpeggio to a sharpened seventh (of the sort Hugo Wolf might later use)",[38] and the downward part as "six and a half bars of pained descent to signify the ongoing burden of the Cross".[39] After the soloist sings a series of melismatic lines, groups of strings and oboes are introduced as counterpoint, echoing motifs from the opening ritornello. The refrain is again taken up in the second stollen, but with significant variations due to the differing text: "It leads me after my torments to God in the Promised Land". After a repeat of the opening ritornello, the final abgesang contains the words, "There at last I will lay my sorrow in the grave, there my Saviour himself will wipe away my tears" ("Da leg ich den Kummer auf einmal ins Grab, da wischt mir die Tränen mein Heiland selbst ab").[26]

Declamatory triplets, spanning the bass register, are responded to in the accompaniment by sighing motifs. A reprise of the orchestral ritornello ends the aria.[37]

In his book L'esthétique de J.-S. Bach, André Pirro describes Bach's use of prolonged notes and sighing motifs, reflecting the suffering on the cross (Kreuz). They give an impression of resistance, of hesitation and hindrance, as the rhythm is arduously dragged along, breaking the momentum of the melody: "They take on a faltering demeanour, both uncertain and overwhelmed, like the stride of a man enchained in shackles."[40] Pirro continues that in the soloist's opening phrases of the aria, the repeated notes have particular importance; the motif not only conveys an impression of encumbrance but also of unrelieved distress; the melismatic vocalise displays an unsure hesitant feeling, like that of a sick pilgrim struggling to make his way along the dark recesses of an unfamiliar flight of steps; it conveys weakness and anxiety; the aria, constantly drawn out, seems imbued with an infinite weariness.[40]

2

| External audio | |

|---|---|

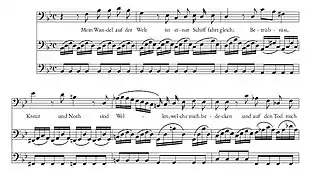

In the second movement, the recitative "Mein Wandel auf der Welt ist einer Schiffahrt gleich" ("My pilgrimage in the world is like a sea voyage"),[26] the sea is evoked by the undulating cello accompaniment of the semiquaver arpeggiation.[41][42] The German text and Drinker's English translation read:

Mein Wandel auf der Welt |

My journey through the world |

In his 1911 biography of Bach, Schweitzer wrote that the composer was often inspired by a single word to create an image of waves,[43] and recommended augmenting the cello with a viola and bassoon to give more weight to the image.[1] According to Gardiner, the style harks back to the 17th-century music of Bach's forebears—the assuring words from the Book of Hebrews, "Ich bin bei dir, Ich will dich nicht verlassen noch versäumen" ("I am with you, I will not leave nor forsake you"), are a "whispered comfort".[39]

3

| External audio | |

|---|---|

The third movement, the da capo aria "Endlich, endlich wird mein Joch wieder von mir weichen müssen" ("Finally, finally my yoke must fall away from me"),[26] illustrates a passage from Isaiah. The full German text with Drinker's English translation reads:

Endlich, endlich wird mein Joch |

Joyful, joyful now am I, |

The lively and joyous concertante is written as a duet for obbligato oboe, bass soloist and continuo, and is full of elaborate coloraturas in the solo parts.[12] According to Gardiner, in the aria "one senses Bach bridging the gap between living and dying with total clarity and utter fearlessness".[39]

4

| External audio | |

|---|---|

The fourth movement, "Ich stehe fertig und bereit, das Erbe meiner Seligkeit mit Sehnen und Verlangen von Jesus Händen zu empfangen" ("I stand ready to receive the inheritance of my divinity with desire and longing from Jesus' hands"),[26] is a recitativo accompagnato with strings.[41] The German text and Drinker's translation read:

Ich stehe fertig und bereit, |

Here ready and prepared I stand |

It begins as an impassioned recitative, with sustained arioso string accompaniment. After seven bars the time signature changes from 4/4 to 3/4, resuming a simple, calm version of the second half of the abgesang from the first movement[44] and repeating words related to the Book of Revelation in a triplet rhythm: "Da wischt mir die Tränen mein Heiland selbst ab" ("There my Saviour Himself wipes away my tears").

According to William G. Whittaker, in an unusual departure from music of that period, Bach displayed "a remarkable stroke of genius" in the reprise of the abgesang for the recitative, marked adagio. It is heard like a distant memory of the cantata's beginning, when the anguished Pilgrim yearned for the Promised Land. Now, however, the mood is of joyful ecstasy; it reaches a climax when the word "Heiland" is heard on a high note in a moment of sustained exaltation; finally, "above a pulsating bassi C, the tear-motive in the upper strings sinks slowly in the depths".[46] Gardiner describes this change similarly: " ... now slowed to adagio and transposed to F minor, and from there by means of melisma floating effortlessly upwards, for the first time, to C major".[39]

5

| External audio | |

|---|---|

The final four-part chorale,[lower-alpha 3] "Komm, o Tod, du Schlafes Bruder" ("Come, o death, brother of sleep"),[26] with the orchestra doubling the vocal parts, is regarded as an inspired masterpiece.[12] The imagery of the sea from the first recitative is revisited in what Whittaker calls an "exquisite hymn-stanza".[47] Death is addressed as a brother of sleep and asked to end the voyage of life by loosening the rudder of the pilgrim's boat or 'little ship' (Schifflein) and bringing it safely to harbour; it marks the end of the cantata's metaphorical journey.[41]

A metrical translation into English was provided by Drinker:[36][48]

Komm, o Tod, du Schlafes Bruder, |

Come, O death, to sleep a brother, |

The melody was written by Johann Crüger and published in 1649.[49]

Bach set the tune in a four-part setting, BWV 301,[50] and introduced dramatic syncopation for the beginning "Komm" ("come").[41] At the end of the penultimate line, torment and dissonance are transformed into glory and harmony and illuminate the words "Denn durch dich komm ich herein / zu dem schönsten Jesulein" ("For through you I will come to my beloved Jesus").[26] As Whittaker comments: "The voices are low-lying, the harmonies are richly solemn; it makes a hushed and magical close to a wonderful cantata."[47] Gardiner notes that it is Bach's only setting of Crüger's melody, which recalls the style of his father's cousin Johann Christoph Bach whom Bach regarded as a "profound composer".[39]

Psychologist and gerontologist Andreas Kruse notes that the chorale conveys the transformation and transition from earthly life to an eternal harbour.[51] He compares the setting to "Ach Herr, laß dein lieb Engelein", the closing chorale of Bach's St John Passion, which is focused on sleep and awakening. Both settings end their works with "impressive composure" ("eindrucksvolle Gefasstheit").[52]

Manuscripts and publication

The autograph score and parts are held by the Berlin State Library, which is part of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. The fascicle numbers are D-B Mus.ms. Bach P 118 for the score (Partitur)[30] and D-B Mus.ms. Bach ST 58 for the parts (Stimmen).[53] It was published in 1863 in volume 12 of the Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe (BGA), edited by Wilhelm Rust. The New Bach Edition (Neue Bach-Ausgabe, NBA) published the score in 1990, edited by Matthias Wendt, and issued critical commentary a year later.[20] It was later published by Carus-Verlag in 1999 as part of Stuttgarter Bach-Ausgaben, a complete edition of Bach's vocal works.[48][54]

Recordings

According to musicologist Martin Elste, the most frequently recorded Bach cantatas are three virtuoso solo cantatas: the Kreuzstab cantata, Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen, BWV 51, for soprano and obbligato trumpet, and Ich habe genug, BWV 82, for bass or soprano.[55] As a vocally demanding and expressive Bach cantata, it has attracted soloists beyond Bach specialists to record it.[55] As of 2022, the Bach Cantatas website lists more than 100 recordings.[56]

Early recordings

An early extant recording of the Kreuzstab cantata was a live concert performance, broadcast in 1939, sung by Mack Harrell with Eduard van Beinum conducting the Concertgebouw Orchestra.[57][58] In 1950, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau was the soloist in the cantata as part of Karl Ristenpart's project to record all Bach church cantatas with the RIAS Kammerchor and its orchestra, broadcast live in church services.[59] A reviewer described the singer at age 26 as "in wonderful voice, even throughout its compass and with a lovely ease at the top of his register", "natural and spontaneous", compared to a 1969 recording with Karl Richter, when the singer put more emphasis on the enunciation of the text.[59]

In 1964, Barry McDaniel was the soloist for a recording in a series of Bach cantatas of Fritz Werner with oboist Pierre Pierlot, the Heinrich-Schütz-Chor Heilbronn and the Pforzheim Chamber Orchestra. A reviewer described it as "a dignified and elevated account of this moving cantata",[60] praising the singer's even and full tone, the sensitivity and intelligence of his interpretation, and the oboists sprightly performance, making the cantata "one of the highlights of the collection".[60]

Complete cycles

In the first complete recording of Bach's sacred cantatas in historically informed performances with all-male singers and period instruments, conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Gustav Leonhardt and known as the Teldec series,[61] the Kreuzstab cantata was recorded in 1976 by soloist Michael Schopper, the Knabenchor Hannover and the Leonhardt-Consort, conducted by Leonhardt. Helmuth Rilling, who recorded all Bach cantatas from 1969 with the Gächinger Kantorei and Bach-Collegium Stuttgart, completing in time for Bach's tricentenary in 1985; they recorded the cantata in 1983, also with Fischer-Dieskau.[61][62] Pieter Jan Leusink conducted all Bach church cantatas with the Holland Boys Choir and the Netherlands Bach Collegium in historically informed performance, but with women for the solo parts. He completed the project within a year on the occasion of the Bach Year 2000.[63] A reviewer from Gramophone wrote: "Leusink's success elsewhere comes largely through his admirably well-judged feeling for tempos and a means of accentuation which drives the music forward inexorably".[64] He recorded the cantata in 1999 with his regular bass Bas Ramselaar. In the cycle by Ton Koopman and the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir, Klaus Mertens was always the soloist, recording the Kreuzstab cantata in 2001. Reviewer Jonathan Freeman-Attwood from Gramophone noted that he gave a sensitive, cultivated rendition, but lacked the dramatic and emotional impact, which he found in McDaniel's 1964 recording with Werner.[65]

Masaaki Suzuki, who studied historically informed practice in Europe, began recording Bach's church cantatas with the Bach Collegium Japan in 1999, at first not aiming at a complete cycle, but completing all of them in 2017. They recorded the cantata in 2008, with Peter Kooy as the singer.[66]

Bass solo works

The Kreuzstab cantata has been coupled with other works by Bach for solo bass, especially Ich habe genug, BWV 82—a paraphrase of the Song of Simeon—and an impassioned cantata taking longing for death as its theme.[67] Sometimes the fragmentary cantata Der Friede sei mit dir, BWV 158, related to peace (Friede) has been added.[28][68][69][70]

In 1977, Max van Egmond was the soloist of BWV 56 and BWV 82, with oboist Paul Dombrecht and Frans Brüggen conducting a Baroque ensemble on period instruments.[67][71] Singer Peter Kooy recorded all three works in 1991, with La Chapelle Royale, conducted by Philippe Herreweghe. A reviewer noted his well focused voice in an intimate rendering full of devotion.[69] The baritone Thomas Quasthoff recorded them in 2004, with oboist Albrecht Mayer, members of the RIAS Kammerchor, the Berliner Barock Solisten with Rainer Kussmaul as concertmaster. A reviewer observed his clear diction and phrasing, and his expressiveness.[69] In 2007, a recording of the three works was released sung by Gotthold Schwarz with the Thomanerchor and the ensemble La Stagione Frankfurt, conducted by Michael Schneider; Schwarz had been a Thomaner, and would later become the 17th Thomaskantor.[72]

In 2013, Dominik Wörner was the soloist for the three cantatas and also the secular cantata Amore traditore, BWV 203, with the ensemble Il Gardellino and oboist Marcel Ponseele, conducted by concertmaster Ryo Terakado. A reviewer characterized Wörner as having a sonorous and free low register and secure high register, with excellent diction and lyrical flow, and able to structure the action well.[68] In 2017, Matthias Goerne recorded BWV 56 and BWV 82 with oboist Katharina Arfken and the Freiburger Barockorchester, conducted by concertmaster Gottfried von der Goltz.[28] A reviewer was impressed by Goerne's "dry" powerful voice, but preferred Harrell's and Fischer Dieskau's "lulling resonance".[73]

Legacy

Albert Schweitzer was an expert on Bach; his organ performances in Strasbourg churches raised funds for his hospital work in West Africa recognized 50 years later by his Nobel Peace Prize. In 1905, Schweitzer wrote a French-language biography of Bach, "J. S. Bach, le musicien poète", published by Breitkopf & Härtel in Leipzig; it was expanded in 1908 to a two-volume German-language version, J. S. Bach; and Ernest Newman produced an English translation in 1911. Schweitzer writes of the cantata: "This is one of the most splendid of Bach's works. It makes unparalleled demands, however, on the dramatic imagination of the singer, who would depict convincingly this transition from the resigned expectation of death to the jubilant longing for death."[74][lower-alpha 4]

Novel

Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen appears in Robert Schneider's 1992 novel, Schlafes Bruder. The protagonist, Elias, improvises on the chorale and decides to end his life.[76] The improvisation is described by the first-person narrator, who refers to the chorale's text. The narrator describes its emotional impact on listeners, hearing a young woman say "Ich sehe den Himmel" ("I see heaven") and saying that his playing could move a listener to the core of their soul (" ... vermochte er den Menschen bis in das Innerste seiner Seele zu erschüttern").[77]

Film

Schlafes Bruder inspired the 1995 film Brother of Sleep, directed by Joseph Vilsmaier.[76] Enjott Schneider composed a toccata for the pivotal scene when Elias improvises during an organ competition at the Feldberg Cathedral, "hypnotising his listeners with demonic organ sounds" ("mit dämonischen Orgelklängen hypnotisiert").[78] Schneider's toccata quotes the chorale "Komm, o Tod, du Schlafes Bruder". The composition is dedicated to Harald Feller, an organist and professor in Munich who supplied ideas and recorded the film's music.[78] It premiered at Feldafing's Heilig-Kreuz-Kirche in 1994, and became an internationally played concert piece.[78]

Opera

The novel inspired a Herbert Willi opera, commissioned by the Opernhaus Zürich, which premiered on 19 May 1996.[79]

Notes

- The header reads: "J. J. Do(min)ica 19 post Trinitatis. Cantata à Voce Sola. è Stromenti." ("J(esu) J(uva) 19th Sunday after Trinity. Cantata for solo voice, and instruments.")

- In his essay on Bach's cantata chorales and autograph manuscripts, Robert G. Marshall explains how the rhythmic character of this particular chorale was "strikingly recast": the stollen melody that conventionally would have started on the downbeat or after a minim rest, now begins with a crotchet rest, cramped into the manuscript; the resulting distinctive syncopation, with two exhortations "Komm" off the beat, was thus "an afterthought".[45]

- The chorale appeared as No. 87 of Bach's "371 Four-part Chorales", edited by Carl Ferdinand Becker and published in 1831 by Breitkopf & Härtel. See 371 Vierstimmige Choralgesänge: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project.

- In German: "Dieses Werk gehört zum Herrlichsten, was Bachs Vermächtnis an uns birgt. Es stellt aber auch Anforderungen ohnegleichen an die dramaturgische Gestaltungskraft des Sängers, der dieses Aufsteigen von der resignierten Todeserwartung zum jubelnden Todessehnen miterleben und gestalten soll".[75]

References

- Schweitzer 1911, p. 255.

- Wolff 2002, pp. 237–257.

- Dürr & Jones 2006, pp. 23–26.

- Buelow 2016, p. 272.

- Dürr & Jones 2006, pp. 22–28.

- Dürr & Jones 2006, pp. 29–35.

- Wolff 2001, p. 7.

- Jones 2013, p. 169.

- Jones 2013, p. 170.

- Jones 2013, pp. 171–172.

- Jones 2013, pp. 175–176.

- Dürr & Jones 2006, p. 582.

- Bach Digital 48 2022.

- Bach Digital 5 2022.

- Bach Archive 2022.

- Blanken 2015, pp. 1–2.

- Blanken 2015, pp. 4–6.

- Blanken 2015, pp. 8–11.

- Bachfest 2016.

- Bach Digital 2018.

- Corall 2015, p. 11.

- Corall 2015, pp. 2, 6–7.

- Blanken 2015, pp. 27.

- Gardiner 2013, p. 349.

- Unger 1997.

- Dellal 2018.

- Chorale Bach Digital 2018.

- Wollny 2017, p. 5.

- Dürr & Jones 2006, pp. 570–572.

- Staatsbibliothek Score 2018.

- Dürr & Jones 2006, p. 580.

- Dürr & Jones 2006, pp. 580–581.

- Wolff 2001, p. 8.

- Wolff 2001, pp. 8–9.

- Schweitzer 1911, p. 380.

- Drinker 1942.

- Dürr & Jones 2006, pp. 582–583.

- Gardiner 2013, pp. 349–350.

- Gardiner 2013, p. 350.

- Pirro 2014, p. 96.

- Dürr & Jones 2006, p. 583.

- Schweitzer 1911, p. 75.

- Schweitzer 1911, p. 75.

- Traupman-Carr 2006.

- Marshall 1970, p. 206.

- Whittaker 1978, p. 278.

- Whittaker 1978, p. 378.

- Carus 2000.

- Chorale 2018.

- Chorale BWV 301 2018.

- Kruse 2014, p. 239.

- Kruse 2014, pp. 239–240.

- Staatsbibliothek Parts 2018.

- Carus Stuttgarter 2000.

- Elste 2000.

- Oron 2022.

- Muziekweb 2022.

- Oron 2016.

- Quinn 2012.

- Quinn 2005.

- McElhearn 2002.

- Barfoot 2002.

- Brilliant Classics 2022.

- Freeman-Attwoood 2000.

- Freeman-Attwoood 2005.

- BIS 2005.

- Anderson 1989.

- Lange 2013.

- Cookson 2010.

- Challenge 2001.

- Shiloni 2014.

- JPC 2007.

- Lemco 2015.

- Schweitzer 1911, pp. 255–256.

- Keuchen 2004, pp. 129–130.

- Spitz 2007.

- Keuchen 2004, p. 136.

- Schott 2018.

- Griffel 2018, p. 427.

Cited sources

Bach Digital

- "Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen BWV 56; BC A 146". Bach Digital. 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz / D-B Mus.ms. Bach P 118". Bach Digital. 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz / D-B Mus.ms. Bach St 58". Bach Digital. 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "Du, o schönes Weltgebäude". Bach Digital. 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Wo soll ich fliehen hin BWV 5; BC A 145". Bach Digital. 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- "Ich elender Mensch, wer wird mich erlösen BWV 48; BC A 144". Bach Digital. 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

Books

- Buelow, George J., ed. (2016). "Leipzig: a Cosmopolitan Trade Cenre". The Late Baroque Era: Vol. 4. From The 1680s To 1740. Berlin: Springer. pp. 254–295. ISBN 978-1-34-911303-3.

- Drinker, Henry S. (1942). Texts of the Choral Works of Johann Sebastian Bach in English translation. Vol. 1. Cantatas 1 to 100. New York City: The Association of American Colleges Arts Program.

- Dürr, Alfred; Jones, Richard D. P. (2006). The Cantatas of J. S. Bach: With Their Librettos in German-English Parallel Text. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929776-4.

- Elste, Martin (2000). "Die geistlichen Kantaten BWV 1–200" [Sacred cantatas BWV 1–200]. Meilensteine der Bach-Interpretation 1750–2000 [Milestones in Bach interpretation 1750–2000] (in German). Berlin: Springer. pp. 151–169. doi:10.1007/978-3-476-03792-3_14. ISBN 978-3-47-603792-3.

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2013). Music in the Castle of Heaven: A Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach. London: Penguin UK. pp. 349–350. ISBN 978-1-84-614721-0.

- Griffel, Margaret Ross (2018). Operas in German: A Dictionary. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-44-224797-0.

- Jones, Richard D. P. (2013). 1717–1750: Music to Delight the Spirit. Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 168–295. ISBN 978-0-19-150384-9.

- Keuchen, Marion (2004). Die "Opferung Isaaks" im 20. Jahrhundert auf der Theaterbühne: Auslegungsimpulse im Blick auf "Abrahams Zelt" (Theater Musentümpel – Andersonn) und "Gottesvergiftung" (Choralgraphisches Theater Heidelberg – Grasmück) (in German). Münster: LIT Verlag. pp. 128–134. ISBN 978-3-82-587196-3.

- Kruse, Andreas (2014). "Zwei Schlusschoräle als Beispiele für den Ausdruck der Erlösungserwartung". Die Grenzgänge des Johann Sebastian Bach: Psychologische Einblicke (in German). Berlin: Springer. pp. 239–243. ISBN 978-3-64-254627-3.

- Pirro, André (2014). The Aesthetic of Johann Sebastian Bach. Translated by Joe Armstrong. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442232914.

- Schweitzer, Albert (1911). J. S. Bach. Vol. 2. Translated by Newman, Ernest. London: Adam and Charles Black. pp. 75, 255–256, 380.

- Spitz, Markus Oliver (2007). Robert Schneider's Novel Schlafes Bruder in the Light of its Screen Version by Joseph Vilsmaier. pp. 319–332. ISBN 978-9-40-120501-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Whittaker, William Gillies (1978). The Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach: Sacred and Secular. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 373–378. ISBN 0-19-315238-X.

- Wolff, Christoph (2002). "Redefining a Venerable Office / Cantor and Music Director in Leipzig: 1720s". Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 237–288. ISBN 978-0-393-32256-9.

Journals

- Blanken, Christine (2015). "A Cantata-Text Cycle of 1728 from Nuremberg: A preliminary report on a discovery relating to J. S. Bach's so-called "Third Annual Cycle"" (PDF). Bach Network. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- Corall, Georg (2015). "Johann Sebastian Bach's Kreuzstab Cantata (BWV 56): Identifying the Emotional Content of the Libretto" (PDF). Limina. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- Marshall, Robert L. (1970). "How J. S. Bach Composed Four-Part Chorales". The Musical Quarterly. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 56 (2): 198–220. doi:10.1093/mq/LVI.2.198. JSTOR 740990.

- Unger, Melvin P. (1997). "Bach's First Two Leipzig Cantatas: The Question of Meaning Revisited". Bach. Riemenschneider Bach Institute. 28 (1/2): 87–125. JSTOR 41640435.

Online sources

- Anderson, Nicholas (1989). "Bach Cantatas 56 & 82". Gramophone. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Barfoot, Terry (February 2002). "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) / Cantatas". musicweb-international.com. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Cookson, Michael (10 March 2010). "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) / Cantatas for Bass". musicweb-international.com. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- Dellal, Pamela (2018). "BWV 56 – Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen". Emmanuel Music. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Freeman-Attwoood, Jonathan (November 2000). "Bach Edition, Volume 4". Gramophone. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Freeman-Attwoood, Jonathan (2005). "Bach Cantatas, Vol. 17". Gramophone. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- Lange, Matthias (2013). "Bach, Johann Sebastian – Solokantaten für Bass / Kernbestand". magazin.klassik.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Lemco, Gary (15 November 2015). "Bach: Cantatas for Bass/ Concerto for Oboe d'amore = Ich hatte viel Bekuemmernis, BWV 21: Sinfonia; Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen, BWV 56; Concerto in A Major for Oboe d'amore, after BWV 1055; Ich habe genug, BWV 82". Audiophile Editions (in German). Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- McElhearn, Kirk (2 April 2002). "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) / Cantatas for Bass". musicweb-international.com. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Oron, Aryeh (2016). "Cantata BWV 56 / Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen / Discography - Part 1". Bach Cantatas Website. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Oron, Aryeh (2022). "Cantata BWV 56 Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen". Bach Cantatas Website. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- Quinn, John (2005). "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) The Cantatas". musicweb-international.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Quinn, John (2012). "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) / The RIAS Bach Cantatas Project". musicweb-international.com. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Shiloni, Ehud (2014). "Kantaten: "Kreuzstab"&"Ich Habe Genug"". jsbach.org. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Traupman-Carr, Carol (2006). "Cantata BWV 56 Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen". The Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Wolff, Christoph (2001). "Bach's Third Yearly Cycle of Cantatas from Leipzig (1725–1727), II" (PDF). Bach Cantatas Website. pp. 7–9. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Wollny, Peter (2017). "Johann Sebastian Bach: Cantatas for Bass" (PDF). Harmonia Mundi. Translated by Charles Johnston. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- "Bachs Kantatendichter identifiziert". Bachfest Leipzig (in German). 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Bachs Kantatendichter identifiziert". Bach Archive (in German). July 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- "J. S. Bach – Cantatas, Vol. 41 (BWV 56, 82, 158, 84)". BIS. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- "J.S. Bach: Complete Sacred Cantatas - Sämtliche geistliche Kantaten". Brilliant Classics. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Stuttgart Bach Edition – Bach vocal". Carus-Verlag. 2000. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Johann Sebastian Bach / Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen / Kantate zum 19. Sonntag nach Trinitatis / BWV 56, 1726". Carus-Verlag. 2000. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Ton Koopman / Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir / Solo Cantatas for Bass". Challenge Records. 2001. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- "BWV 56.5". bach-chorales.com. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "BWV 301". bach-chorales.com. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Johann Sebastian Bach: Kantaten BWV 56,82,158". jpc.de. 2006. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Eduard van Beinum / Live : The radio recordings; live : the radio recordings; vol.1". Muziekweb. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- "Toccata "Schlafes Bruder"". Schott Music. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

Further reading

- Mincham, Julian (2010). "Chapter 29 Bwv 56 – The Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach". jsbachcantatas.com.

External links

- Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen, BWV 56: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Komm, o Tod, du Schlafes Bruder noten.bplaced.net

- Cantate voor bas, koor en orkest BWV.56, "Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen" muziekweb.nl

- Ambrose, Z. Philip. "BWV 56 Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen". University of Vermont. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- Dagmar Hoffmann-Axthelm: Bachkantaten in der Predigerkirche / BWV 56 / Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen bachkantaten.ch

- BWV 56, performed by Peter Kooy (bass), Marcel Ponseele (oboe) and Collegium Vocale Gent, directed by Philippe Herreweghe on YouTube

- Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen, BWV 56: performance by the Netherlands Bach Society (video and background information)

- Audio recordings of BWV 56 sung by William Parker, baritone, and the Arcadian Academy and Baroque Choral Guild, directed by Nicholas McGegan: BWV 56/1, BWV 56/2, BWV 56/3, BWV 56/4, BWV 56/5