Retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukoencephalopathy and systemic manifestations

Retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukocencephalopathy and systemic manifestations (RVCL or RVCL-S, also previously known as retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy, RVCL; or cerebroretinal vasculopathy, CRV; or hereditary vascular retinopathy, HVR; or hereditary endotheliopathy, retinopathy, nephropathy, and stroke, HERNS) is an inherited condition resulting from a frameshift mutation in the C-terminal region of the TREX1 gene.[1] This disease affects small blood vessels, leading to damage of multiple organs including but not limited to the retina and the white matter of the central nervous system. Patients with RVCL develop vision loss, brain lesions, strokes, brain atrophy, and dementia. Patients with RVCL also exhibit other organ involvement, including kidney, liver, gastrointestinal tract, thyroid, and bone disease. Symptoms of RVCL commonly begin between ages 35 and 55, although sometimes disease onset occurs earlier or later. The overall prognosis is poor, and death can sometimes occur within 5 or 10 years of the first symptoms appearing, although some patients live more than 20 years after initial symptoms.[2] Clinical trials are underway, as are efforts to develop personalized medicines for patients with RVCL.

| Retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukocencephalopathy (RVCL or RVCL-S) | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukoencephalopathy (RVCL or RVCL-S) |

| |

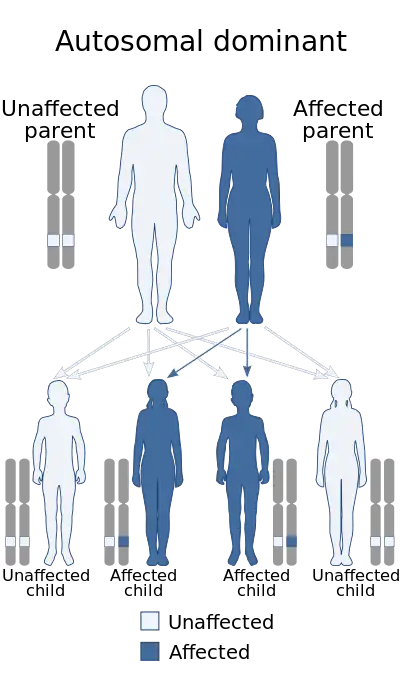

| Diagram depicts the mode of inheritance of this condition | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, neurology, ophthalmology, genetics |

| Usual onset | Onset usually around age 35-55. |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | This disease is inherited (genetic). |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing confirming a C-terminal frameshift mutation between the exonuclease domain and transmembrane domain--on only one allele--of the TREX1 gene. |

Presentation

- For most patients, disease onset is between ages 35 and 55. Earliest onset is usually not before age 35. Late onset is usually not after age 55.[3]

- RVCL affects multiple organs. All patients develop brain and eye disease, leading to disability, vision loss, and premature death.

- All patients with RVCL develop kidney and liver disease, with elevated alkaline phosphatase.[3] Some patients develop bone lesions (osteonecrosis) as well as hypothyroidism.[3] Sometimes patients also develop gastrointestinal symptoms or bleeding.[3]

- RVCL is associated with progressive deterioration in visual acuity due to multifocal microvascular disease, retinal neovascularization leading, and/or glaucoma. Retinal microvascular disease is noninflammatory and resembles that of diabetic retinopathy. This leads to partial or complete vision loss.[3]

- Headaches due to multiple factors including brain lesions, edema, and papilledema.

- Mental confusion, loss of cognitive function, loss of memory, slowing of speech and hemiparesis due to brain lesions. Some patients have Jacksonian seizures or grand mal seizures.

- Progressive neurologic deterioration unresponsive to systemic immunosuppression including corticosteroid therapy and chemotherapeutic agents.

- Autopsy typically demonstrates discrete, often confluent, foci of coagulative necrosis in the cerebral white matter, with intermittent findings of fine calcium deposition within necrotic foci. Additionally, tissues exhibit vasculopathic changes involving both arteries and veins of medium and small caliber in the cerebral white matter. There is fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls with extravasation of fibrinoid material into adjacent parenchyma present in both necrotic and non-necrotic tissue. Vessels can exhibit obliterative fibrosis in all the layers of vessel walls, as well as perivascular, adventitial fibrosis with limited intimal thickening.

- In rare cases, RVCL has been associated with severe disease involving other organs outside the brain and the eye (e.g., osteonecrosis requiring joint replacement, gastrointestinal ischemia leading to bowel resection, or liver failure requiring liver transplantation).

Genetics

RVCL is caused by mutations in the TREX1 gene.[3] The official name of the TREX1 gene is "three prime repair exonuclease 1". The normal function of the TREX1 gene is to provide instructions for making the 3-prime repair exonuclease 1 enzyme. This enzyme is a DNA exonuclease, which means it trims molecules of DNA by removing DNA building blocks (nucleotides) from the ends of the molecules. In this way, it breaks down unneeded DNA molecules or fragments that may be generated during genetic material in preparation for cell division, DNA repair, cell death, and other processes.

Changes (mutations) to the TREX1 gene can result in a range of conditions, one of which is RVCL. The mutant TREX1 protein is produced and mislocalized.[4] Haploinsufficiency of TREX1 does not explain the disease, since the parents of patients with Aicairdi-Goutieres syndrome, a disease characterized by insufficient TREX1 activity, are completely healthy with only one functional TREX1 allele.

Different mutations in the TREX1 gene have also been identified in people with disorders involving the immune system. These disorders include a chronic inflammatory disease called Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome, as well as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), including a rare form of SLE called chilblain lupus that mainly affects the skin. Those diseases, which are inflammatory, likely have a completely distinct mechanism compared with that of RVCL.

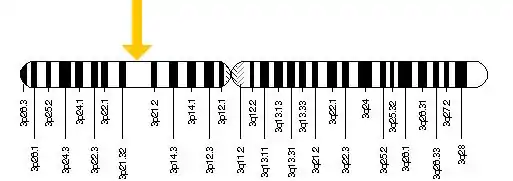

The TREX1 gene is located on chromosome 3: base pairs 48,465,519 to 48,467,644

Pathogenesis

The main pathologic process centers on small blood vessels that prematurely "drop out" and disappear. The retina of the eye and white matter of the brain appear to be among the most sensitive to this pathologic process. Over a five- to ten-year period, this vasculopathy (blood vessel pathology) results in vision loss and destructive brain lesions with neurologic deficits and death.

Although brain and eye disease are universally present in patients with RVCL, the disease is truly a multi-system disorder characterized by chronic kidney disease, liver disease, and frequently other manifestations including gastrointestinal disease, osteonecrosis, and hypothyroidism.[5]

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

- Brain tumors

- Diabetes

- Macular degeneration

- Telangiectasia (Spider veins)

- Hemiparesis (Stroke)

- Glaucoma

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE (same original pathogenic gene, but definitely a different disease because of a different mutation in TREX1))

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Behçet's disease

- Lymphomatoid granulomatosis

- Vasculitis

Treatment

Currently, there is no therapy that is proven to prevent the blood vessel deterioration. In 2021, Dr. Jonathan Miner of the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) in Philadelphia, and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (Penn Medicine), initiated a clinical trial of crizanlizumab for RVCL.[6] The University of Pennsylvania also sponsors RVCL patient support groups, and collaborates with the RVCL Research Center at Washington University (WashU) on clinical trials and longitudinal studies.

Miner also established a large RVCL Research Center, which is conducting clinical trials, performing basic research, and developing novel personalized therapies for RVCL. This includes small molecular inhibitors (to be taken as pills) and gene therapy approaches, with the goal of fully correcting the disease-causing mutation.[6] Developing these personalized therapies is a challenging process that will take years.

History

- 1985–1988: CRV (Cerebral Retinal Vasculopathy) was discovered by multiple investigators including Dr. Gil Grand, Dr. John P. Atkinson, and colleagues at Washington University School of Medicine (WashU).

- 1988: 10 families worldwide were identified as having CRV (now known as RVCL or RVCL-S)

- 1991: Related disease reported, HERNS (Hereditary Endiotheliopathy with Retinopathy, Nephropathy and Stroke – UCLA

- 1998: Related disease reported, HRV (Hereditary Retinal Vasculopathy) – Leiden University, Netherlands

- 2001: Localized to Chromosome 3.

- 2007: The specific genetic defect in all of these families was discovered in a single gene called TREX1 on chromosome 3.

- 2008: Name changed to AD-RVCL Autosomal Dominant-Retinal Vasculopathy with Cerebral Leukodystrophy (one of several name changes)

- 2009: Testing for the disease becomes available to persons 21 and older.

- 2011: Approximately 20 families worldwide were identified as having RVCL

- 2012: Obtained mouse models for further research and to test therapeutic agents

- 2021: At least 42 families and 200 patients worldwide are known to have RVCL (or RVCL-S).

- 2021: Dr. Jonathan Miner of the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) initiates the second clinical trial for RVCL, in collaboration with Dr. Rennie Rhee and Dr. Andria Ford. Miner also establishes an International Registry in collaboration with colleagues.[7]

- 2022: The RVCL Research Center at Penn announces successful preclinical development of gene therapies for RVCL.[6] A multi-year process to prepare for clinical trials begins.[8]

- 2023: The University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia) announces more progress in the ongoing development of personalized medicine for patients with RVCL.[9] Dr. Miner reports that the RVCL Research Center at Penn has now identified 60 families worldwide.

References

- "What is RVCL? (also known as RVCL-S, CRV, or HERNS) | RVCL Research Center | Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania". www.med.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-31.

- "Retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program".

- "What is RVCL? (also known as RVCL-S, CRV, or HERNS) | RVCL Research Center | Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania". www.med.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-31.

- Richards, Anna; van den Maagdenberg, Arn M. J. M.; Jen, Joanna C.; Kavanagh, David; Bertram, Paula; Spitzer, Dirk; Liszewski, M. Kathryn; Barilla-Labarca, Maria-Louise; Terwindt, Gisela M.; Kasai, Yumi; McLellan, Mike (2007). "C-terminal truncations in human 3'-5' DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause autosomal dominant retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy". Nature Genetics. 39 (9): 1068–1070. doi:10.1038/ng2082. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 17660820. S2CID 3475346.

- "What is RVCL? (also known as RVCL-S, CRV, or HERNS) | RVCL Research Center | Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania". www.med.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-31.

- "Finding a Cure for RVCL | RVCL Research Center | Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania". www.med.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-31.

- "What is RVCL? | RVCL Research Center | Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania". www.med.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-31.

- Miner, Jonathan J.; Fitzgerald, Katherine A. (March 2023). "A path towards personalized medicine for autoinflammatory and related diseases". Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 19 (3): 182–189. doi:10.1038/s41584-022-00904-2. ISSN 1759-4804. PMC 9904876.

- "Treating Retinal Vasculopathy with Cerebral Leukoencephalopathy". www.pennmedicine.org. Retrieved 2023-07-16.