Atyap subgroups and clans

The subgroups of the Atyap ethnolinguistic group as suggested by Meek (1931:2) include the Katab (Atyap) proper, Morwa (Asholyio), Ataka (Atakad) and Kagoro (Agworok) which he deems may be regarded as a single tribe and each division/unit as a sub-tribe because they speak a common tongue and show cultural trait uniformity. McKinney (1983:290), thereafter, opined that Kaje (Bajju) should likewise be included with the above, rather than with the Kamantan (Anghan), Jaba (Ham), Ikulu (Bakulu) and Kagoma (Gwong) due to the linguistic and cultural similarities they share with the 'Katab' group, adding that Jaba and Kagoma seem farther away linguistically and culturally to the aforementioned.[1][2] The clans may refer to further grouping within each subgroup.

Groupings

[3] According to James (2000), subgroups in the Nerzit (also Nenzit, Netzit) or Kataf (Atyap) group are as follows:

- Atyap (Kataf, Katab)

- Bajju (Kaje, Kajji)

- Aegworok (Kagoro, Oegworok, Agorok)

- Sholio (Moro'a, Asholio)

- Fantswam (Kafanchan)

- Bakulu (Ikulu)

- Angan (Kamantan, Anghan)

- Attakad (Attakar, Attaka, Takad)

- Tyacherak (Kachechere, Attachirak, Atacaat)

- Terri (Challa, Chara)

[4] However, Akau (2014:xvi) gave the list of the constituent sub-groups of the Atyap group as follows:

- The A̠gworok sub-group

- The A̠sholyo (A̠sholyio) sub-group

- The A̠takat sub-group

- The A̠tuku (A̠tyuku) sub-group

- The A̠tyecharak (A̠tyeca̠rak) sub-group

- The A̠tyap Central sub-group

- The Ba̠jju sub-group

- The Fantswam sub-group

- The Anghan sub-group (also related to the Ham group)

- The Bakulu sub-group (also related to the Adara group)

[5] In terms of spoken language, nevertheless, only seven of the sub-groups given by both James (2000) and Akau (2014) are listed by Ethnologue as speakers of the Tyap language with SIL code: "kcg". Those seven are:

- Tyap: central (Tyap spoken by the Atyap of Atyap Chiefdom, "Atyap Mabatado")

- Tyap: Fantswam (spoken by the Fantswam)

- Tyap: Gworok (spoken by the Agworok or Oegworok)

- Tyap: Sholyio (spoken by the Asholyo

- Tyap: Takad (spoken by the Atakad or Atakad or Takad)

- Tyap: Tuku (spoken by the Atuku or Atyuku)

- Tyap: Tyecarak (spoken by the Atyecharak).

The other four, namely:

- Jju (spoken by the Bajju has the SIL code: "kaj";

- Nghan (spoken by the Anghan has the SIL code: "kcl"; and

- Kulu (spoken by the Bakulu has the SIL code: "ikl".)

- Cara (spoken by the Cara or Chara has the SIL code: "cfd".)

Of these four, only Jju is a Tyapic language. For the other, Nghan is Gyongic, Kulu is of Northern plateau i.e. the Adara-ic languages, and Cara Beromic just like Iten and Berom itself.

Atyap "proper" sub-group

Clans

One feature of the Atyap (a subgroup in the larger Atyap/Nenzit also spelled Netzit, Nietzit, Nerzit ethnolinguistic group) is the manner in which responsibilities are shared among its four clans, some of which has sub-clans and sub-responsibilities. The possession of totems, taboos and emblems which come in form of designs, structures, and animals is another important aspect in the history and tradition of the Atyap people. According to oral tradition, all the four clans of the Atyap people have different emblems, totem, and taboo and they vary from clan to clan and from sub-clan to sub-clan. This is considered a common practice among the people because they most of the time used these emblems as a way of identification. Apart from the emblems and totems, some clans have certain animals or plants which they also consider as taboos and in some cases also used them for rituals. Oral tradition further has it that such animals are usually reverend in the area to date.

The exogamous belief within the clans that members of a clan had a common descent through one ancestor, prevented inter-marriages between members of the same clan. Inter-clan and inter-state marriage were encouraged.

Aminyam clan

Not much is known about this clan but it has 2 sub-clans:

- Aswon (Ason)

- Afakan (Fakan)

Cows are considered as the Minyam's totem but the people have mystified a cow by seeing it as a hare with its ear as horns. These "horns" of the hare are locally called A̱ta̱m a̱swom and the Minyam clan members have high respect for them because they always touch the "horns" and swear by them when an offense is committed. Once the accused person swears, then nothing will be said or done again but to just wait for the outcome.

A̱gbaat clan

It has 3 sub-clans:

- Akpaisa

- Akwak (Kakwak) and

- Jei

They had primacy in both cavalry and archery warfare and handled the army. The Agbaat clan, especially the Jei sub-clan, was considered the best warriors both in Cavalry and archery warfare. Agbaat clan leader, therefore, became the commander-in-chief of the Atyap army. The post of "A̱tyutalyen", a military public relations officer who announced the commencement and termination of each war, was held by a member of the Agbaat clan The totem for the Agbaat clan is the large crocodile called Tsang. Oral tradition has it that the Agbaat consider the Tsang as their ‘friend’ and ‘brother’ and the relationship is also said to have developed when the Atyap people were fleeing from their enemies. As they moved, they got to a very big river that they could not cross, and suddenly crocodiles appeared and formed a bridge for them to cross. When the other clans tried to cross by the same means, the crocodile swam away. This, according to oral tradition, explains why today, it is said that the Agbaat people can play with a crocodile without being harmed, and given the respect the Agbaat people have for the crocodile, they bury its dead body when they find it killed anywhere. Similarly, when an Agbaat man accidentally kills a crocodile (Tsang), he must hurriedly run to a forest for some special medicine and ritual. But if the killing is by design, then it is believed that the entire clan will perish.

A̱ku clan

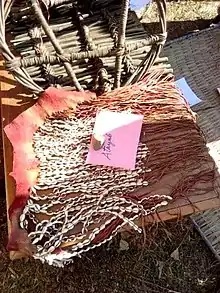

The Aku clans were the custodians of the paraphernalia of the A̱bwoi and led in the rites for all New initiates and ceremonies. They performed initiation rites for all new initiates. To prepare adherents for initiations, their bodies were smeared with mahogany oil (A̱myia̱ a̱koo) and were forced to take exhaustive exercise before they were ushered into the shrine. They had to swear to keep all secrets related to the Abwoi. Abwoi communicated to the people using a dry shell of bamboo having two open ends. One end was covered with spider's web while the other end was blown. It produced a mysterious sound interpreted by the people as the voice of a deceased ancestor. This human manipulation enabled the male elders of the society to control the behaviour and conscience of society. Abwoi leaves (Na̱nsham) a species of shea, were placed on farms and housetops to scare away thieves since the Abwoi was believed to be omnipresent and omniscient. Abwoi was thus, a unifying religious belief among the Atyap that wedded immense powers in a society whose secrets were kept through a web of spies and informants who reports the activities of saboteurs. Any revelation of Abwoi secrets could be meted with capital punishment. Women were also implored to keep society's secrets, particularly, those related to way. To ensure that war secrets did not leak to the opponents, women were made to wear tswa a̱ywan (woven raffia ropes) for 6 months in a year. During this period, they were to refrain from gossip, "foreign" travel, and late cooking. At the end of the period, it was marked by Song-A̱yet (or Swong A̱yet) also known as the Ayet festival, celebrated in April, when women were free to wear fashionable dresses.

These fashionable dresses included the A̱ta̱yep made of strips of leader and decorated with cowrie shells.

The A̱yiyep, another version of this, had dyed ropes of raffia sewn together into loin cloth. Women also wore the Gyep a̠ywan (written "oyam" by Tremearne (1914) and Meek (July 1928), a lumber ornament which they considered phallic in origin, and Wilson-Haffenden (1929:173-173) reported that it was often smeared with red oil and was said to have previously consisted of the stalk only and considers it a sign of "fertility" or a "good luck" charm)[6] for the Song-A̱yet ceremony.

It was woven from palm fibre into a thick made in the shape of a truncated cone or mushroom. It was tied around the waist using a projection from a cord. For men, the muzurwa was the major dress, which was made of tanned leather and properly oiled. The rich in society had the edges of this dress adorned with beads and cowries. The dress was tied around the waist with the aid of gindi (leather strap). By the late 18th century, a pair of short knickers called Dinari, made of cloth, became part of the men's attire. Men also had their hair plaited and at times decorated with cowrie shells. They wore raffia caps (A̱ka̱ta) decorated with dyed wool and ostrich feathers. Their bodies were painted with white chalk (A̱bwan) and red ochre (tswuo)

For the Aku clan, oral tradition has it that their emblem or totem is the ‘Male’ shea Tree (locally called Na̱nsham). The people's belief about this tree was that the tree can be felled, but its wood is not to be used for making fire for cooking. It is believed that if an Aku man eats food cooked with Na̱nsham wood his body would develop sores. Also, if a bunch of Na̱nsham leaves was placed at the door of a house, no Aku woman dared entered such a house because it was also considered a serious taboo. Nevertheless, if these inadvertently happen, Dauke (2004) explained that certain rituals would be performed to cleanse the victims from such curses otherwise they would die.

A̱shokwa (Shokwa) clan

The A̱shokwa clan was in charge of rainmaking and flood control rites. It also has no sub-clans. The A̱shokwa for example, was in-charge of rites associated with rainmaking and control of floods. During dry spells in the rainy season, the A̱shokwa clan leader, the chief priest, and Rainmaker had to perform rites for rainmaking. When rainfall was too high resulting in floods and the destruction of houses and crops, the same officers of the clan were called up to perform rites related to controlling rain.

According to Achi (1981), the emblem or totem of the A̱shokwa clan was a lizard known as Tatong (ant-eater). According to them, A̱shokwa, the founder of the clan, was trying to light his house, when suddenly the Tatong (appeared and asked) who he was and where his relatives were. A̱shokwa told the Tatong that he had no relatives or kindred. The Tatong sympathized with A̱shokwa and assured him that ‘God’ would increase his family. This prophesy later came true, and A̱shokwa ordered all his children to rever the Tatong at all times. Henceforth, tradition also has it that the A̱shokwa clan began to regard the Tatong as a ‘relative’, and if they found its dead body anywhere they would bury it and give it all the respect it deserves, holding a funeral for it as they do for their elderly persons.

Oral tradition further confirmed that, should an A̱shokwa man kill a Tatong accidentally, rain would fall, even in the middle of the dry season. This respect shown to the Tatong by the A̱shokwa is shared by most of the Atyap clans, these members of another clan who lived near the A̱shokwa and who accidentally killed a Tatong took its body to the A̱shokwa people for burial. It is claimed that the most binding oath an A̱shokwa can make is by the Tatong and they also do not name their siblings after their emblem animal.[7]

Relationship between the clans

According to Gaje and Daye (Pers. Comm. 2008), the Aku and Ashokwa clans share a closer affinity in contradistinction with their relationship with the other clans and sub-clans. Aku and Ashokwa clans have no subclans probably because they chose not to emphasize the issue of subdivisions amongst themselves. This close relationship is traceable to their early arrival to their present settlement; the Aku and the Ashokwa were said to have arrived at their present abode before the other clans and sub-clans. Dauke (2004) further pointed out that the Aku and the Ashokwa were legendarily "discovered" because they were "met" there by the other Atyap people who arrived later.

The Shokwa were aboriginal, having allegedly emerged from out of the Kaduna river, and were considered rainmakers. The Aku was also aboriginal, having been associated with the Shokwa but emerging later. The others were strangers adopted into the society, forming sub-clans.

Several other legendary versions of oral tradition also exist in Atyap's history of migration and settlement. First, it is said that after the Agbaat clan came and settled in their new place, one of the sub-clans of the Agbaat went on a hunting expedition and accidentally "came across" the Ashokwa clan along the River Kaduna performing certain religious rites. When the Ashokwa saw the Agbaat coming their way, they fled out of fear and the Agbaat pursued them. When the Agbaat finally caught the Ashokwa, they discovered that they speak the same (Tyap) language and share the same belief and thus accepted them as their brothers. Dauke (2004) also gave another version of the tradition on the "discovery" of the Aku and Ashokwa clans. According to him, the Aku was proverbially said to have "sprung out" from the hoof marks of the Agbaat horsemen as they pursued the Ashokwa. In other words, while the Agbaat were pursuing the Ashokwa, the hooves of their horsemen opened a termite's mound from where the Aku emanated. This explains why the Aku to date bears the nickname of "Bi̠n Cíncai", which means, "relatives of the termites". The above traditions and stories of the "discovery" of the Aku and Ashokwa clans portray the fact that these two clans can likely be reconsidered as those representing the earlier migrants who first came and occupied the present Atyap land. However, oral tradition also has it that all the four clans and sub-clans of the Atyap people are presently found in their large numbers in many villages within the Atyap Chiefdom largely due to population increase and the need to stay closer to farmlands. They also intermingle with one another within most of the villages in Atyap land where the Akpaisa, the Jei, and the Akwak (Kakwak) sub-clans of the Agbaat clan are found, including the Minyam villages.

Atyecharak sub-group

The Atyecharak or A̠tyeca̠rak (Tyap: central: A̠tyecaat; Hausa: Kachechere or Kacecere) were the original inhabitants of the land presently occupied by the Agworok (another Atyap subgroup), scattered by the latter about as a result of a war fought between the two, waged by the Agworok against the Atyecharak who took two of Agworok's people as slaves annually as taxation for occupying their territory. A part of the Atyecharak moved north to Atyap (central/proper) land where they had been since then, in and around the village bearing their name in the Atyap Chiefdom and today form a part of the Atyap Traditional Council. The others are found in the Tachirak area of Gworok (Kagoro) Chiefdom also a part of the traditional council there.[8]

Agworok "Oegworok" sub-group

Asholyio sub-group

Fantswam sub-group

Bajju group

References

- In-citations

- McKinney, C. (1983). "A Linguistic Shift in Kaje, Kagoro, and Katab Kinship Terminology". Ethnology. 22 (4): 281–293. doi:10.2307/3773677. JSTOR 3773677. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- Meek, C. K. (1931), p.59

- James, Ibrahim (2000). The Settler Phenomenon in the Middle Belt and the Problem of National Integration in Nigeria: The Middle Belt (Ethnic Composition of the Nok Culture).

- Akau, K. T. L. (2014). The Tyap-English Dictionary (in Tyap and English). Benin City. p. xvi. ISBN 978-978-0272-15-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Tyap". Ethnologue. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Wilson-Haffenden, J. (1929). "132. Some Notes on Fork Guards in Nigeria". Man. 29: 172–174. doi:10.2307/2789646. JSTOR 2789646. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- Ninyio, Y. S. (2008). Pre-colonial History of Atyab (Kataf). Ya-Byangs Publishers, Jos. p. 93. ISBN 978-978-54678-5-7.

- Afuwai, Yanet. The Place of Kagoro in the History of Nigeria.

- Bibliography

- Meek, C. K. (1931). Tribal Studies in Northern Nigeria. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., Broadway House, London. pp. 58–76.