Atari 1050

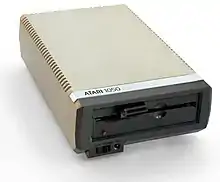

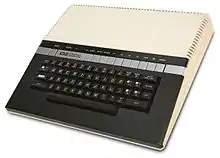

The Atari 1050 was a floppy disk drive for the Atari 8-bit family home computers, released in June 1983. It was compatible with the 90 kB single-density mode of the original Atari 810 it replaced, and added a new "enhanced" or "dual density" mode that provided 130 kB. Based on a half-height Tandon mechanism, it was much smaller than the 810 and matched the styling of the new 600XL and 800XL machines.

By the time it was available, a wide variety of third party drives had been introduced for the 8-bit platform, many of which were faster and offered true double-density support for 180 kB. The lack of double-density support on the 1050 was a mystery to onlookers at the time, as the hardware had full support for this format. The launch was further marred by releasing it with the older Atari DOS 2.0S, S for "single", which did not support the 130 kB capacity. Atari replaced 2.0 with DOS 3.0 which supported the enhanced density mode, but used an entirely new format that was incompatible with earlier disks. The release of DOS 2.5 in 1985 finally addressed these issues.

The 1050 was launched directly into the rise of the Commodore 64 and the videogame crash of 1983 when sales of the entire 8-bit line plummeted. When Jack Tramiel purchased Atari in 1984 there were warehouses filled with unsold 1050s, which delayed production of a replacement. It was not until 1987 that the Atari XF551 was introduced, offering both double-density and double-sided capabilities and a double-speed transfer mode.

History

810 and 815

When the 8-bit series was first announced in 1978 it was often shown with two floppy disk drive systems, the 810 and 815. The 810 was an entry-level model, supporting only single-density FM encoding at 90 kB total storage. The 815 used two double-density MFM encoding drives in a single large housing, each drive offering 180 kB of storage. For reasons unknown, the 815 was produced only in small numbers starting in 1980 and then abandoned, leaving the platform only with the 810 which were described by InfoWorld as "noisy, slow and inefficient."[1]

New design

In April 1982, Atari began the process of designing an improved version of the 8-bit series, which were to be known as the 1000 and 1000XL. Among the changes was a new design language from Regan Cheng using off-white and black plastics with brushed metal overlay on switches and other fixtures. Along with the machines, a new line of peripherals would be released with matching styling, numbered in the 1000's in the same fashion that earlier devices had been numbered in the 400 and 800 series.

For reasons unknown, Atari abandoned these plans and instead introduced only one model, now known as the 1200XL. When it was introduced at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in December 1982, it was shown with the new Atari 1010 cassette deck, and the 1020 plotter and 1025 printers.[2][lower-alpha 1] There was no sign of a new floppy drive, and one reviewer noted that when he went looking all he could find was the "old model 810 clunkers", speculating that "we will be seeing a new drive from Atari within the next half year".[2]

This prediction came true; when the 1200XL finally reached the market in June 1983, it was accompanied by the new Atari 1050. It offered the new "enhanced" or "dual density" option that improved formatted capacity to 130 kB, and replaced the 810 in the market.[3] To take advantage of the new enhanced density mode, a new version of Atari DOS was needed, 3.0. This was not available at launch, and the early examples shipped with DOS 2.0S instead, meaning they could not take advantage of the new features.[4]

The required DOS 3.0 eventually shipped several months later. However, it used an entirely new format using 1 kB "blocks" rather than the standard 128 byte "sectors", meaning that disks that were formatted with DOS 3 could not be read or written on other machines unless they also updated to 3.0. The move to blocks meant that the minimum file size was also 1 kB, and in the era of small files this resulted in significant wasted space. This led most users to shun 3.0, and reviewers to state flatly that "This product should be avoided. It's a shame so many newer Atari users have been saddled with it."[4]

By this time, increasing sales of the 400 and 800 and the failure of a new drive to appear from Atari led to a thriving market for third-party drives and alternative DOSes, many of which provided true double-density support using the format originally introduced on the 815. An August 1984 review in Antic compared the 1050 with four 3rd party drives and the 810; the 1050 was beaten by all but the 810 in both capacity and speed. The 1050 was described as "a no-frills drive", especially compared to the Rana 1000 and Indus GT, which offered double-density, various high-speed modes, front-panel displays, and many other features. The lack of double density support was described as "a mystery".[5][lower-alpha 2]

The problems with DOS 3.0 were finally addressed in 1984 with the introduction of the "long awaited" DOS 2.5.[6] This returned to the 2.0-style formatting even for enhanced density, allowing DOS 2 and 2.5 users to swap disks as long as they were in single-density format. By this time, most of the 3rd party DOSes had already added support for enhanced mode.[7]

Modifications

As was the case for the 810 before it, the 1050 was the subject of a number of 3rd party upgrades that improved performance in various ways. Notable among these was the ICD Doubler, which added true double-density support allowing it to store 180 kB of data. This also added a high-speed mode that had been originally introduced in the Happy 810 modifications for the 810, increasing transfers from 19.2 kbps to 52 kbps. Happy also updated their original system for the 1050, becoming the Happy 1050, and like the Doubler it provided double-density support and its Warp Speed system. SpartaDOS, also from ICD, supported both the Doubler and Happy systems, offering much better performance from such systems.[8] Both were also supported by most other 3rd party DOSes on the platform.[4]

Price war

The new XL series machines were launched into the middle of a price war between Commodore International and Texas Instruments, which quickly drove everything but the Commodore 64 and Apple II from the market.[9] Sales of the 8-bits plummeted. At the same time, the videogame crash of 1983 was in full-swing. By the start of 1984, Atari was losing millions of dollars a day,[10] and their owners, Warner Communications, became desperate to sell off the "loss-plagued" company.[11]

Atari was purchased by Jack Tramiel, formerly of Commodore, in June 1984.[12] The new management arrived to find warehouses filled with XL systems and peripherals. They put the existing stock on the market for fire-sale prices while they developed new very-low-cost versions of the machines. These emerged as the XE series, which were presented at the January 1985 Consumer Electronics Show, along with a restyled 1050 called the XF521. They continued to show the new drive through 1985 and 1986, but it disappeared without ever shipping.[13][14]

By 1986 the new Atari ST series was doing well in the market and interest in the 8-bit platforms waned. Even as stocks of the 1050 dwindled and then ran out entirely, no new drive was launched. An even further upgraded model, the double-sided, double-density XF551 was being teased through this period, but again the drive was not released. It was not until 1987, six months after 1050s had run out, that the XF551 finally shipped, and only after the threat of a lawsuit from Nintendo forced their hand.[15]

Design

The 1050 moved to a half-height mechanism, 1+5⁄8 inches (41.3 mm) tall, compared to the 810's full-height 3+1⁄4 inches (82.6 mm). Its new case was designed by Tom Palecki. In keeping with most of Tandon's mechanisms, a rotating arm on the front of the drive was used to lock the floppy into place. The drive also had its own read/write LED beside the down position of the latch. The power switch was located directly below the LED, with a power indicator LED to its right. The back held the two drive number selection switches on the left, two SIO ports in the center, and the power ring jack on the right.[16]

The drive controller was a single card, unlike the two or three of the 810. It used a MOS 6507 as the SIO bus controller, running at 1 MHz rather than 500 kHz of the 810. The 6507 was aided by a MOS 6532 RIOT/PIA and a 6810 static RAM. The drive controller was the Western Digital WD2793 using MFM encoding for double-density support, although units built starting in the fall of 1985 used the WD2797. The drive ignored the alignment hole, and thus did not need the two-hole "flippy disk" to use the second side. It did respect the write-protect notch, so using the back side of a disk required another notch to be punched in the disk, or the drive to be slightly modified to ignore the notch.[16]

When used in 810 compatible mode, the drive formatted disks with 40 tracks and 18 sectors per track, for a total of 720 sectors per disk. Each sector held 128 bytes, for a total storage of 92,160 bytes/disk (90 kB). This was the normal FM encoded single-density format used by most machines of the late 1970s. Normally, when used with MFM encoding for double-density, the number of bytes per sector was doubled to 256 and the layout was otherwise unchanged. Instead, Atari's format retained the original 128 byte sectors and increased the number per track to 26, thereby providing 40 x 26 x 128 = 133,120 bytes per side, 130 kB. While Atari's documentation referred to this as double density, users used the term "enhanced" or "dual density" to distinguish it from the true double-density systems already in the market.[16]

In contrast to the 810, which saw several upgrades during its time on the market, the 1050 saw only one major change. Production was first set up in Singapore in May 1983 and ran until December 1984, accounting for the majority of the production run. These units used the Tandon mechanism. In November 1984, production moved to Hong Kong, changing to a largely identical mechanism from World Storage Technology. Production returned to Singapore for the final run using Tandon from October 1985 to December 1985.[16]

Notes

- The 1025 was a relabeled Okidata Microline 80.

- Double-density requires no change to the disk mechanism, it is accomplished entirely within the drive controller electronics and was fully supported by the 1050s hardware.

References

Citations

- DeWitt, Robert (26 July 1982). "Percom double-density disk drive for Atari micros". InfoWorld. p. 48.

- Anderson 1983, p. 116.

- Current 2021, p. 3.2.1.

- Clausen 1985, p. 41.

- Dziefielewski 1984, p. 80.

- Clausen 1985, p. 40.

- Clausen 1985, pp. 40–45.

- Clausen 1985, p. 43.

- Nocera, Joseph (April 1984). "Death of a Computer". Texas Monthly. Vol. 12, no. 4. Emmis Communications. pp. 136–139, 216–226. ISSN 0148-7736.

Once before, Commodore had put out a product in a market where it chief competitor was TI: a line of digital watches. TI started a price war and drove Commodore out of the market. Tramiel was not about to let that happen again.

- Shrage, Michael (15 October 1983). "Atari Sends Warner Loss to $122 Million". The Washington Post.

...which reported a $180 million loss this quarter...

- "Warner sells Atari operations". UPI. 2 July 1984.

- Sanger, David (3 July 1984). "Warner Sells Atari To Tramiel". The New York Times. p. D1.

- Floyd, Bob (11 January 1985). "XF521 Disk Drive". Saint Paul Computer Enthusiasts.

- Friedland, Nat (April 1985). "First Look Inside the New Atari Super Computers". ANTIC. p. 19.

- Ratcliff 1989, p. 9.

- Current 2021, p. 3.2.2.

Bibliography

- Clausen, Eric (July 1985). "Everything you wanted to know about every DOS". ANTIC. p. 40-45.

- Current, Michael (12 October 2021). "atari-8-bit/faq".

- Dziefielewski, Lawrence (August 1984). "Disk Drive Survey". ANTIC. pp. 36–39, 80–81.

- Kruse, Richard (August 1984). "Do More With DOS 2.0: The Atari 1050 does the trick". ANTIC. pp. 31–32.

- Ratcliff, Matthew (February 1989). "Atari XF551 Disk Drive". ANALOG. No. 69. pp. 9, 40.

- Anderson, John (1983). "New Member of the Family: Atari 1200". In Small, David; Small, Sandy; Blank, George (eds.). The Creative Atari. Creative Computing. pp. 116–117.