Astor Place Riot

The Astor Place Riot occurred on May 10, 1849, at the now-demolished Astor Opera House[1] in Manhattan and left between 22 and 31 rioters dead, and more than 120 people injured.[2] It was the deadliest to that date of a number of civic disturbances in Manhattan, which generally pitted immigrants and nativists against each other, or together against the wealthy who controlled the city's police and the state militia.

| Astor Place Riot | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Theatre Riots | |||||||

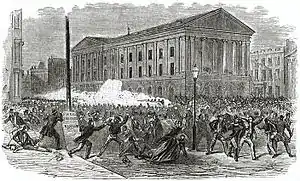

Rioters at the Astor Place Opera House on the night of the riot. In the foreground is the New York Militia firing upon rioters. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Pro-Edwin Forrest Rioters | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Captain Isaiah Rynders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 10,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

The riot resulted in the largest number of civilian casualties due to military action in the United States since the American Revolutionary War, and led to increased police militarization (for example, riot control training and larger, heavier batons).[3] Its ostensible genesis was a dispute between Edwin Forrest, one of the best-known American actors of that time, and William Charles Macready, a similarly notable English actor, which largely revolved around which of them was better than the other at acting the major roles of Shakespeare.40°43′48″N 73°59′28″W

Background

In the first half of the 19th century, theatre as entertainment was a mass phenomenon, and theatres were the main gathering places in most towns and cities. As a result, star actors amassed an immensely loyal following, comparable to modern celebrities or sports stars. At the same time, audiences had always treated theaters as places to make their feelings known, not just towards the actors, but towards their fellow theatergoers of different classes or political persuasions, and theatre riots were not a rare occurrence in New York.[4]

In the early- to mid-19th century, the American theatre was dominated by British actors and managers. The rise of Edwin Forrest as the first American star and the fierce partisanship of his supporters was an early sign of a home-grown American entertainment business. The riot had been brewing for 80 or more years, since the Stamp Act riots of 1765, when an entire theatre was torn apart while British actors were performing on stage. British actors touring around the United States had found themselves the focus of often violent anti-British anger, because of their prominence and the lack of other visiting targets.[5]

The fact that both Forrest and Macready were specialists in Shakespeare can be ascribed to the Bard's reputation in the 19th century as the icon of Anglo-Saxon culture. Ralph Waldo Emerson, for instance, wrote in his journal that beings on other planets probably called the Earth "Shakespeare."[6] Shakespeare's plays were not just the favorites of the educated: in gold rush California, miners whiled away the harsh winter months by sitting around campfires and acting out Shakespeare's plays from memory; his words were well known throughout every stratum of society.[7]

Genesis

The roots of the riot were multifold, but had three main strands:

- A dispute between Macready, who had the reputation as the greatest British actor of his generation, and Forrest, the first real American theatrical star. Their friendship became a virulent theatrical rivalry, in part because of the poisonous Anglo-American relations of the 1840s. The question of who was the greater actor became a notorious bone of contention in the British and, particularly, the American media, which filled columns with discussions of their respective merits.

- A growing sense of cultural alienation from Britain among mainly working-class Americans, along with Irish immigrants; though nativist Americans were hostile to Irish immigrants, both found a common cause against the British.

- A class struggle between those groups who largely supported Forrest, and the largely Anglophile upper classes, who supported Macready. The two actors became figureheads for Britain and the United States, and their rivalry came to encapsulate two opposing views about the future of American culture.

According to historian Nigel Cliff in The Shakespeare Riots, it was ironic that both were famous as Shakespearean actors: in an America that had yet to establish its own theatrical traditions, one way to prove its cultural prowess was to do Shakespeare as well as the British, and even to claim that Shakespeare, had he been alive at the time, would have been, at heart at least, an American.[8]

Proximate causes

Macready and Forrest each toured the other's country twice before the riot broke out. On Macready's second visit to America, Forrest had taken to pursuing him around the country and appearing in the same plays to challenge him. Given the tenor of the time, most newspapers supported the "home-grown" star Forrest.[9] On Forrest's second visit to London, he was less popular than on his first trip, and he could only explain it to himself by deciding that Macready had maneuvered against him. He went to a performance of Macready playing Hamlet and loudly hissed him. For his part, Macready had announced that Forrest was without "taste".[4] The ensuing scandal followed Macready on his third and last trip to America, where half the carcass of a dead sheep was thrown at him on the stage.[10] The climate worsened when Forrest instigated divorce proceedings against his English wife for immoral conduct, and the verdict came down against Forrest on the day that Macready arrived in New York for his farewell tour.

Forrest's connections were substantial with working people and the gangs of New York: he had made his debut at the Bowery Theatre, which had come to cater mostly to a working class audience, drawn largely from the violent, immigrant-heavy Five Points neighborhood of lower Manhattan a few blocks to the west. Forrest's muscular frame and impassioned delivery were deemed admirably "American" by his working-class fans, especially compared to Macready's more subdued and genteel style.[4] Wealthier theatergoers, to avoid mingling with the immigrants and the Five Points crowd, had built the Astor Place Opera House near the junction of Broadway (where the entertainment venues catered to the upper classes) and the Bowery (the working-class entertainment area). With its dress code of kid gloves and white vests, the very existence of the Astor Opera House was taken as a provocation by populist Americans for whom the theater was traditionally the gathering place for all classes.[11]

.jpg.webp)

Macready was scheduled to appear in Macbeth at the Opera House, which had opened itself to less elevated entertainment, unable to survive on a full season of opera, and was operating with the name "Astor Place Theatre".[12] Forrest was scheduled to perform Macbeth on the same night, only a few blocks away at the huge Broadway Theater.[13]

Riot

On May 7, 1849, three nights before the riot, Forrest's supporters bought hundreds of tickets to the top level of the Astor Opera House, and brought Macready's performance of Macbeth to a grinding halt by throwing at the stage rotten eggs, potatoes, apples, lemons, shoes, bottles of stinking liquid, and ripped up seats. The performers persisted in the face of hissing, groans, and cries of "Shame, shame!" and "Down with the codfish aristocracy!", but were forced to perform in pantomime, as they could not make themselves heard over the crowd.[4] Meanwhile, at Forrest's May 7 performance, the audience rose and cheered when Forrest spoke Macbeth's line "What rhubarb, senna or what purgative drug will scour these English hence?"[14]

After his disastrous performance, Macready announced his intention to leave for Britain on the next boat, but he was persuaded to stay and perform again by a petition signed by 47 well-heeled New Yorkers – including authors Herman Melville and Washington Irving – who informed the actor that "the good sense and respect for order prevailing in this community will sustain you on the subsequent nights of your performance."[4] On May 10, Macready once again took the stage as Macbeth.[14]

On the day of the riot, police chief George Washington Matsell informed Caleb S. Woodhull, the new Whig mayor, that there was not sufficient manpower to quell a serious riot, and Woodhull called out the militia. General Charles Sandford assembled the state's Seventh Regiment in Washington Square Park, along with mounted troops, light artillery, and hussars, a total of 350 men who would be added to the 100 policemen outside the theater in support of the 150 inside. Additional policemen were assigned to protect the homes in the area of the city's "uppertens", the wealthy and elite.[4]

On the other side, similar preparations took place. Tammany Hall man Captain Isaiah Rynders was a fervent backer of Forrest and had been one of those behind the mobilization against Macready on May 7. He was determined to embarrass the newly ensconced Whig powers, and distributed handbills and posters in saloons and restaurants across the city, inviting working men and patriots to show their feelings about the British, asking "Shall Americans or English Rule This City?" Free tickets were handed out to Macready's May 10 show, as well as plans for where people should deploy.[4]

By the time the play opened at 7:30 as scheduled, up to 10,000 people[4] filled the streets around the theater. One of the most prominent among those who supported Forrest's cause was Ned Buntline, a dime novelist who was Rynders' chief assistant.[4][15] Buntline and his followers had set up relays to bombard the theater with stones, and fought running battles with the police. They and others inside tried (but failed) to set fire to the building, many of the anti-Macready ticket-holders having been screened and prevented from coming inside in the first place.[4] The audience was in a state of siege; nonetheless, Macready finished the play, again in "dumb show", and only then slipped out in disguise.

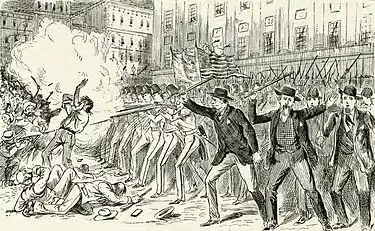

Fearing they had lost control of the city, the authorities called out the troops, who arrived at 9:15, only to be jostled, attacked, and injured. Finally, the soldiers lined up and, after unheard warnings, opened fire, first into the air[4] and then several times at point blank range into the crowd. Many of those killed were innocent bystanders, and almost all of the casualties were from the working class; seven of the dead were Irish immigrants.[4] Dozens of injured and dead were laid out in nearby saloons and shops, and the next morning mothers and wives combed the streets and morgues for their loved ones.[16]

_-p152_New_York_-_the_fight_between_Rioters_and_Militia.jpg.webp)

The New York Tribune reported: "As one window after another cracked, the pieces of bricks and paving stones rattled in on the terraces and lobbies, the confusion increased, till the Opera House resembled a fortress besieged by an invading army rather than a place meant for the peaceful amusement of civilized community."[17]

The next night, May 11, a meeting was called in City Hall Park which was attended by thousands, with speakers crying out for revenge against the authorities whose actions they held responsible for the fatalities. During the melée, a young boy was killed. An angry crowd headed up Broadway toward Astor Place and fought running battles with mounted troops from behind improvised barricades,[4] but this time the authorities quickly got the upper hand.[18]

Consequences

Between 22 and 31 rioters were killed, and 48 were wounded. Fifty to 70 policemen were injured.[19] Of the militia, 141 were injured by the various missiles.[20] Three judges presided over a related trial, including Charles Patrick Daly, a judge on the New York Court of Common Pleas,[1] who pressed for convictions.[4]

The city's elite were unanimous in their praise of the authorities for taking a hard line against the rioters. Publisher James Watson Webb wrote:

The promptness of the authorities in calling out the armed forces and the unwavering steadiness with which the citizens obeyed the order to fire on the assembled mob, was an excellent advertisement to the Capitalists of the old world, that they might send their property to New York and rely upon the certainty that it would be safe from the clutches of red republicanism, or chartists, or communionists [sic] of any description.[4]

Astor Opera House did not survive its reputation as the "Massacre Opera House" at "DisAstor Place," as burlesques and minstrel shows called it. It began another season, but soon gave up the ghost, the building eventually going to the New York Mercantile Library. The elite's need for an opera house was met with the opening of the Academy of Music, farther uptown at 15th Street and Irving Place, away from the working-class precincts and the rowdiness of the Bowery. Nevertheless, the creators of that theater learned at least one lesson from the riot and the demise of the Astor Opera House: the new venue was less strictly divided by class than the old one had been.[4] Though Forrest's reputation was badly damaged,[21] his heroic style of acting can be seen in the matinee idols of early Hollywood and performers such as John Barrymore.[22]

According to Cliff, the riots furthered the process of class alienation and segregation in New York City and America; as part of that process, the entertainment world separated into "respectable" and "working-class" orbits. As professional actors gravitated to respectable theaters and vaudeville houses responded by mounting skits on "serious" Shakespeare, Shakespeare was gradually removed from popular culture into a new category of highbrow entertainment.[23]

In popular culture

- Richard Nelson's play Two Shakespearean Actors deals mainly with the events surrounding and leading up to the riot.[24]

- The riot was featured in a 2006 episode of Weekend Edition on NPR.[25]

- The riot is mentioned in Booth, a 2022 novel by Karen Joy Fowler. This novel tells the story of the Booth family of American Shakespearean actors whose members included John Wilkes Booth.[26]

References

Notes

- Staff (September 20, 1899). "Charles P. Daly Dead" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- Cliff, pp. 228, 241

- Cliff, pp. 241, 245

- Burrows & Wallace, pp.761–766

- Cliff, pp. 8, 125–9

- Cliff, p. 264

- Cliff, pp. 13–18, 260–263

- Cliff, pp. 120–121

- Cliff 2007, pp. 133–137.

- Cliff, pp. 150–164, 176

- Cliff, pp. xiv–xvi

- Cliff, p. 205

- Cliff, pp. 165–184

- Levine, Lawrence W. (1988). Highbrow/lowbrow : the emergence of cultural hierarchy in America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39076-8. OCLC 17804284.

- Cliff, pp. 196–199

- Cliff, pp. 209–233

- Staff (11 May 1849) New York Tribune (supplement)

- Cliff, pp. 234–239

- Gilge, Paul A. "Riots" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366. pp.1006–1008

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- Cliff 2007, p. 248.

- Morrison 1999, p. xii, 177.

- Cliff 2007, pp. 263–265.

- Rich, Frank (17 January 1992). "War of Hams Where the Stage Is All". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- "Remembering New York City's Opera Riots". NPR.org. 13 May 2006. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Fowler, Karen Joy (2022). Booth. Putnam. ISBN 978-0593331439.

Bibliography

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

- Cliff, Nigel (2007). The Shakespeare Riots: Revenge, Drama, and Death in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-345-48694-3.

- Morrison, Michael A. (1999). John Barrymore, Shakespearean Actor. Cambridge Studies in American Theatre and Drama. Vol. 10. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521629799.

External links

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Account of the Terrific and Fatal Riot at the New-York Astor Place Opera House (1849) by H.M. Ranney at the Internet Archive.

- Kellem, Betsy Golden (19 July 2017). "When New York City Rioted Over Hamlet Being Too British". Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian Institution.