Arthur Kinnaird, 11th Lord Kinnaird

Arthur Fitzgerald Kinnaird, 11th Lord Kinnaird, KT (16 February 1847 – 30 January 1923) was a British principal of The Football Association and a leading footballer, considered by some journalists as the first football star.[2] He played in nine FA Cup Finals, a record that stands to this day.[3] His record of five wins in the competition stood until 2010, when it was broken by Ashley Cole.[4]

The Lord Kinnaird | |

|---|---|

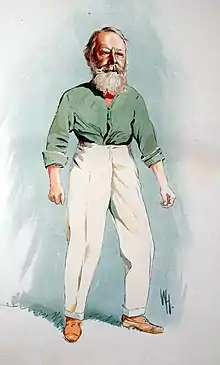

Portrait of Kinnaird by Alexander Bassano, c. 1905 | |

| Born | Arthur Fitzgerald Kinnaird 16 February 1847 Kensington, England |

| Died | 30 January 1923 (aged 75) England |

| Occupation(s) | Football player and executive |

| Known for | |

Kinnaird also served as president of The FA for 33 years.[1] For his contributions to football and the FA Cup, he was given the FA Cup trophy itself to keep in 1911 when a new trophy was commissioned.[5][6]

Life

Kinnaird's father, Arthur Kinnaird, 10th Lord Kinnaird, was a banker and MP before taking up his seat in the House of Lords. Kinnaird's mother was Mary Jane Kinnaird and he was born in London. He was educated at Cheam School, Eton College and Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating BA in 1869.[7] He worked in the family bank, becoming a director of Ransom, Bouverie & Co in 1870. This bank later merged with others in 1896 to become Barclays Bank of which he was a main board director until his death.

In 1875, he married Mary Alma Victoria Agnew (1854–1923), the daughter of Sir Andrew Agnew, 8th Baronet, and Lady Mary Noel, and had seven children, including :[8][9]

- Douglas Arthur Kinnaird, who was born on 20 August 1879 and served during the First World War as a captain in the 1st Battalion of the Scots Guards; he died on 24 October 1914 and is buried at Ypres in Belgium.[10]

- Kenneth Fitzgerald Kinnaird (1880–1972), who inherited his father's titles; he married Frances Clifton (1876–1960) and was the father of Graham Charles Kinnaird (1912–1997), 13th Lord Kinnaird, upon whose death the titles became dormant.

- Arthur Middleton Kinnaird, who was born on 20 April 1885 and served as a lieutenant in the 1st Battalion of the Scots Guards; he died on 27 November 1917 and is buried at Ruyaulcourt.[11]

- Patrick Kinnaird (1898–1948), who married, in 1921, Margaret Stella Wright (div.) and, in 1925, Violet Sandford.

Football career

Player

Kinnaird first played football while at Cheam School and was captain of the school team in 1859, aged 12, for a match against Harrow School. He continued to play football at Eton College, winning the House Cup in 1861 with Joynes's House, but was never selected for the school eleven. He first played association football, which was codified in 1863, early in 1866.

As a player, Kinnaird had a remarkable record in the FA Cup. He played in a record nine FA Cup finals. He was on the winning side three times with Wanderers and twice with the Old Etonians, and celebrated his fifth Cup Final victory by standing on his head in front of the pavilion. In the course of his career as a Cup Final player, Kinnaird played in every position, from goalkeeper to forward. It was while playing in goal for Wanderers in the 1877 final that he suffered the indignity of scoring the first significant own goal in football history, accidentally stepping backwards over his own goal line after fielding an innocuous long shot from an Oxford University forward. The match finished 1–1 and Wanderers won with a second goal in extra time. Some time after the match, for unknown reasons, the FA struck the Oxford goal from the records, changing the official score to 2–0 (although if Oxford had not scored, there would have been no reason for the game to go to extra time, so by rights they should have annulled Wanderers' second goal as well).[12] For the next century, all sources reported the score of the match as 2–0.[12] In the 1980s, after fresh research into contemporary reports of the game by football historians, the FA reinstated the Oxford goal, and now regard the official final score of the 1877 final as 2–1.[13]

Although he was born in Kensington, London, as a son of an old Perthshire family, Kinnaird also played for Scotland.[14] He played in three of Scotland's first five matches, which were subsequently classified as unofficial, and in Scotland's second official match: played on 8 March 1873 at The Oval.[14] All of these games were against England; who were the only other national team then in existence. On 13 March 1875, Arthur captained the Old Etonians team in the FA Cup final against Royal Engineers, the game ended in a draw of 1-1 after extra time. A replay was scheduled for 16 March 1875 and Old Etonians lost to the Royal Engineers (2-0) during a replay and this was the first time a replay was held.[15]

Playing style

He was renowned as perhaps the toughest tackler of his day, giving rise to the (probably apocryphal) story that his wife once expressed the fear that he would "come home one day with a broken leg." A friend is said to have responded: "You must not worry, madam. If he does, it will not be his own." Posterity has awarded Arthur Kinnaird the reputation of being fond of 'hacking', i.e. deliberately kicking his opponents. This is not entirely fair: reports from his playing days do not criticise him, and he owes his notoriety to an oft-repeated anecdote which first appeared in an October 1892 issue of Pastime magazine, a weekly sporting journal that was edited by Nicholas Lane 'Pa' Jackson, founder of the Corinthian Football Club and a committee member of the Football Association.

Jackson wrote: 'The keen rivalry which at one time existed between the Old Etonians and Old Harrovians lent an additional zest to the matches between them, and in one of these Lord Kinnaird's energy was expended as much on the shins of his opponents as on the ball. This at length caused a protest from the captain of the Harrovians, who asked, 'Are we going to play the game, or are we going to have hacking?' 'Oh, let us have hacking!' was the noble reply.' Jackson later reveals that the opposing captain was Charles Alcock, which pinpoints the likely origin of the anecdote to a game on 16 November 1872, described as 'a friendly, but most vicious game of football' by The Graphic newspaper. Alcock and Morton Peto Betts were sufficiently disabled to be unable to play for England in the first official international, two weeks later.

Sportswriters and fellow internationals queued to pay tribute to Kinnaird's skill as a footballer both during and after his career. He was, according to "Tityrus" (J.A.H. Catton), editor of the Athletic News:

"of yeoman build and shaggy auburn beard, [and] did not quite look the part of a Scottish laird, until one spoke to him, and heard his rich, resonant voice and his short ejaculatory sentences. Of course, he had the voice and manner of an educated man of distinction.

"He was a leader, and above all things, a muscular type of Christian... As a player, in any position, [he] was an examplar of manly robust football. He popularised the game by his activity as a footballer among every class. He was at much at home with the boys of the Polytechnic, London, as he was with the Old Etonians.

"There was a time when the white ducks of Kinnaird, for he always wore trousers in a match, and his blue and white quartered cap were as familiar on the field as the giant figure of W.G. Grace with his yellow and red cricket cap... Lord Kinnaird used to say that he played four or five matches a week and never grew tired, but he added, late in life, that he would never have been allowed to stay on the field five minutes in these latter days. Nevertheless, he was fair, above board, and was prepared to receive all the knocks that came his way without a trace of resentment."

Administrator

As an administrator, Kinnaird was an FA committeeman at the age of 21, in 1868. He became treasurer nine years later and president 13 years after that, replacing Major Francis Marindin in 1890. He was to remain president for the next 33 years, serving alongside long-serving vice-president Charles Crump, until their deaths in 1923, just days before the opening of Wembley Stadium.

He was an all-round sportsman, twice winning a blue at tennis, in 1868 and 1869, while at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was first in an international canoe race at the 1867 Paris Exhibition.[16] He was Cambridge University swimming and fives champion, and won the Eton College 350 yards race in 1864.

Other interests

Outside of sport, he was president of the YWCA and the YMCA in England,[17] a director of Barclays Bank and Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1907, 1908 and 1909. He was Honorary Colonel of the Tay Division Submarine Miners a Volunteer unit of the Royal Engineers based in Dundee.[18]

Honours

Wanderers

Old Etonians

He was appointed a Knight of the Thistle by George V in the 1914 Birthday Honours.[19][20] This gave him the Post Nominal Letters "KT" for Life.

Portrayals

Kinnaird is one of the main characters in the Netflix mini-series, The English Game (2020), portrayed by Edward Holcroft.[21][22]

Bibliography

- Arthur Kinnaird: First Lord of Football, Andy Mitchell. CreateSpace, 2011. ISBN 978-1-4636-2111-7. (Revised and republished in 2020).

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- The Official History Of The Football Association, Bryon Butler, ISBN 0-356-19145-1

- Association Football and the Men Who Made It, William Pickford and Alfred Gibson. London: Caxton 1906.

- The Story of Association Football, "Tityrus" (J.A.H. Catton). Cleethorpes: Soccer Books, 2006 reprint of 1926 original. ISBN 1-86223-119-2.

- Burke's Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage, 100th Edn, London, 1953.

- Hesilrige, Arthur G. M. (1921). Debrett's Peerage and Titles of courtesy. 160A, Fleet street, London, UK: Dean & Son. p. 526.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)

References

- "Poly History – Arthur Kinnaird – Polytechnic Football Club". polytechnicfc.co.uk. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- "Arthur Kinnaird: First Lord of Football". Scottish Sport History – devoted to our sporting heritage.

- "Kinnaird's FA Cup". Scottish Sport History - devoted to our sporting heritage.

- "100 years on, the man so great he was given the Cup to keep". The Independent. 20 February 2011.

- "100 years on, the man so great he was given the Cup to keep". The Independent. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- "Birmingham's proud trophy-making history". BBC News. 23 June 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- "Kinnaird, the Hon. Arthur Fitzgerald (KNRT864AF)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Arthur Fitzgerald Kinnaird, 11th Baron Kinnaird". geni.com.

- Hesilrige 1921, p. 527.

- "We Remember The Hon. Douglas Arthur Kinnaird". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- The Hon. Arthur Middleton Kinnaird on Lives of the First World War

- Warsop, Keith (2004). The Early FA Cup Finals and the Southern Amateurs. SoccerData. p. 47. ISBN 1-899468-78-1.

- "Cup Final Statistics". The Football Association. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- Brown, Alan; Tossani, Gabriele (19 September 2019). "Scotland – International Matches 1872–1880". RSSSF. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Lewis, Rhett (7 April 2022). "Arthur Kinnaird: Soccer's First Superstar Winning 5 FA Cups". History Of Soccer. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- "Kinnaird the canoeist". Scottish Sport History – devoted to our sporting heritage.

- Brown, Paul (29 May 2013). The Victorian Football Miscellany. Superelastic. ISBN 978-0-9562270-5-8.

- Burke's.

- Mitchell, Molli (25 March 2020). "The English Game: Who was Arthur Kinnaird? Was he real?". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- "No. 28842". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 June 1913. pp. 4875–4882.

- "Who stars in Netflix's 'The English Game'?". Newsweek. 20 March 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- Anderson, Hayley (20 March 2020). "The English Game cast: Who is in the cast of The English Game?". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

External links

![]() Media related to Arthur Kinnaird, 11th Lord Kinnaird at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Arthur Kinnaird, 11th Lord Kinnaird at Wikimedia Commons