Art in bronze and brass

Art in bronze and brass dates from remote antiquity. These important metals are alloys, bronze composed of copper and tin and brass of copper and zinc.

Proportions of each alloy vary slightly. Bronze may be normally considered as nine parts of copper to one of tin. Other ingredients which are occasionally found are more or less accidental. The result is a metal of a rich golden brown colour, capable of being worked by casting — a process little applicable to its component parts, but peculiarly successful with bronze, the density and hardness of the metal allowing it to take any impression of a mould, however delicate. It is thus possible to create ornamental work of various kinds.

Casting

The process of casting in bronze and brass is known as cire perdue, and is the most primitive and most commonly employed through the centuries, having been described in by the monk Theophilus, and also by Benvenuto Cellini. Briefly, it is as follows: a core, roughly representing the size and form of the object to be produced, is made of pounded brick, plaster or other similar substance and thoroughly dried. Upon this the artist overlays his wax, which he models to the degree required in his finished work. Passing from the core through the wax and projecting beyond are metal rods. The modelling being completed, called lost-wax casting, the outer covering which will form the mould has to be applied; this is a liquid formed of clay and plaster sufficiently thin to find its way into every detail of the wax model. Further coatings of liquid are applied, so that there is, when dry, a solid outer coating and a solid inner core held together by the metal rods, with the work of art modelled in wax between. Heat is applied and the wax melts and runs out, and the molten metal is poured in and occupies every detail which the wax had filled. When cool, the outer casing is carefully broken away, the core raked out as far as possible, the projecting rods are removed and the object modelled in wax appears in bronze. If further finish is required, it is obtained by tooling.[1]

Greek and Roman

Copper came into use in the Aegean area near the end of the predynastic age of Egypt about 3500 BC. The earliest known implement is a flat celt, which was found on a Neolithic house-floor in the central court of the palace of Knossos in Crete, and is regarded as an Egyptian product. Bronze was not generally used until a thousand years or more later. Its first appearance is probably in the celts and dagger-blades of the Second City of Troy, where it is already the standard alloy of 10% tin. It was not established in Crete until the beginning of the Middle Minoan age (MMI, c. 2000 BC). The Copper Age began in northern Greece and Italy c. 2500 BC, much later than in Crete and Anatolia, and the mature Italian Bronze Age of Terremare culture coincided in time with the Late Aegean (Mycenaean) civilisation (1600–1000 BC). The original sources both of tin and copper in these regions are unknown.[1]

Earliest implements and utensils

Tools and weapons, chisels and axe-heads, spearheads or dagger-blades, are the only surviving artifacts of the Copper Age, and do not show artistic treatment. But some Early Minoan pottery forms are plainly copied from metal prototypes, cups and jugs of simple construction and rather elaborate design. The cups are conical and sometimes a stem-foot; there are oval jars with long tubular spouts, and beaked jugs with round shoulders set on conical bodies. Heads of rivets which tie the metal parts together are often reproduced as a decorative element in clay. The spouted jars and pierced type of axe-head indicate that metallurgical connections of Early Minoan Crete were partly Mesopotamian.

Minoan and Mycenaean

Weapons and implements

It is known that Middle Minoan bronze work flourished as an independent native art. To the very beginning of this epoch belongs the largest sword of the age, found in the palace of Malia. It is a flat blade, 79 cm long, with a broad base and a sharp point; there is a gold and crystal hilt but no ornament on the blade. A dagger of somewhat later date, now in the Metropolitan Museum of New York is the earliest piece of decorated bronze from Crete. Both sides of the blade are engraved with drawings: bulls fighting and a man hunting boars in a thicket. Slightly later again (MM III) are a series of blades from mainland Greece, which must be attributed to Cretan craftsmen, with ornament in relief, or incised, or inlaid with gold, silver and niello. The most elaborate inlays, pictures of men hunting lions and cats hunting birds, are on daggers from the shaftgraves of Mycenae. These large designs cover the whole of the flat blade except its edge, but on swords, best represented by finds at Knossos, the ornament is restricted to the high midribs which are an essential feature of the longer blades. The type belongs to the beginning of the Late Minoan (Mycenaean) age. The hilt is made in one piece with the blade; it has a horned guard, a flanged edge for holding grip-scales, and a tang for a pommel. The scales were ivory or some other perishable substance and were fixed with bronze rivets; the pommels were often made of crystal. A rapier from Zapher Papoura (Knossos) is 91.3 cm long; its midrib and hilt-flange are engraved with bands of spiral coils, and its rivet-heads (originally gold-cased) with whorls. Ordinary Mycenaean blades are enriched with narrow mouldings, parallel to the midribs of swords and daggers, or to the curved backs of one-edged knives. The spearheads have hammered sockets. Other tools and implements are oval two-edged knives, square-ended razors, cleavers, chisels, hammers, axes, mattocks, ploughshares and saws. Cycladic and mainland Greek (Helladic) weapons show no ornament but include some novel types. A tanged spearhead has a slit (Cycladic) or slipped (Helladic) blade for securing the shaft; and the halberd, a west European weapon, was in use in the Middle Helladic Greece. There are few remains of Mycenaean metal armour; a plain cheek-piece from a helmet comes from Ialysos in Rhodes, and a pair of greaves from Enkomi in Cyprus. One of the greaves has wire riveted to its edge for fastening.[1]

Utensils

Middle and Late Minoan and Mycenaean vessels are many. First in size are some basins found at Tylissos in Crete, the largest measuring 1.40 metres in diameter. They are shallow hemispherical bowls with two or three loop-handles riveted on their edges, and are made in several sections. The largest is composed of seven hammered sheets, three at the lip, three in the body, and one at the base. This method of construction is usual in large complicated forms. The joints of necks and bodies of jugs and jars were often masked with a roll-moulding. Simpler and smaller forms were also cast. The finest specimens of such vases come from houses and tombs at Knossos. Their ornament is applied in separate bands, hammered or cast and chased, and soldered on the lip or shoulder of the vessel. A richly decorated form is a shallow bowl with wide ring-handle and flat lip, on both of which are foliate or floral patterns in relief.[1]

A notable shape, connecting prehistoric with Hellenic metallurgy is a tripod-bowl, a hammered globular body with upright ring-handles on the lip and heavy cast legs attached to the shoulder.

Statuettes

Purely decorative work is rare among Minoan bronzes, and is comparatively poor in quality. There are several statuettes, very completely modelled but roughly cast; they are solid and unchased, with blurred details. Well known are a figure of a praying or dancing woman from the Troad, now at Berlin, and another from Hagia Triada; praying men from Tylissos and Psychro, another in the British Museum, a flute-player at Leyden, and an ambitious group of a man turning a somersault over a charging bull, known as the Minoan Bull-leaper. This last was perhaps a weight; there are smaller Mycenaean weights in the forms of animals, filled with lead, from Rhodes and Cyprus. Among the latest Mycenaean bronzes found in Cyprus are several tripod-stands of simple openwork construction, a type that has also been found with transitional material in Crete and in Early Iron Age (Geometric) contexts on the Greek mainland. Some more elaborate pieces, cast in designs of ships and men and animals, belong to a group of bronzes found in the Idaean cave in Crete, most of which are Asiatic works of the 9th or 8th centuries BC. The openwork tripods may have had the same origin. They are probably not Greek.

Hellenic and Italian

Geometric Period

During the Dark Ages of the transition from bronze to iron, the decorative arts stood almost still but industrial metalwork was freely produced. There are a few remains of Geometric bronze vessels, but as in the case of the Early Minoan material, metal forms are recorded in their pottery derivatives. Some vase-shapes are clearly survivals from the Mycenaean repertory, but a greater number are new, and these are elementary and somewhat clumsy, spherical or biconical bodies, huge cylindrical necks with long band-handles and no spouts. Ceramic painted ornament also reflects originals of metal, and some scraps of thin bronze plate embossed with rows of knobs and lightly engraved in hatched or zig-zag outline doubtless represent the art which the newcomers brought with them to Greek lands. This kind of decorative work is better seen in bronzes of the closely related Villanova culture of north and central Italy. A novel feature is the application of small figures in the round, particularly birds and heads of oxen, as ornaments of handles, lids and rims. The Italian Geometric style developed towards complication, in crowded narrow bands of conventional patterns and serried rows of ducks; but contemporary Greek work was a refinement of the same crude elements.

Engraving appears at its best on the large catch-plates of fibulae, some of which bear the earliest known pictures of Hellenic mythology. Small statuettes of animals were made for votive use and also served as seals, the devices being cast underneath their bases. There is a large series of such figures, mostly horses, standing on engraved or perforated plates, which were evidently derived from seals; among the later examples are groups of men and centaurs. Pieces of tripod-cauldrons from Olympia have animals lying or standing on their upright ring-handles, which are steadied by human figures on the rims. Handles and legs are cast, and are enriched with graceful geometric mouldings. The bowls are wrought, and their shape and technique are pre-Hellenic. Here are two of the elements of classical Greek art in full course of development: the forms and processes of earlier times invigorated by a new aesthetic sense.[1]

Oriental influence

A third element was presently supplied in the rich repertory of decorative motives, Egyptian and Assyrian, that was brought to Europe by Phoenician traders or fetched from Asia by adventurous Greeks. A vast amount of oriental merchandise found its way into Greece and Italy around 800 BC. There is some uncertainty about the place of manufacture of much of the surviving bronze work, but the same doubt serves to emphasize the close resemblance that these pieces, Phoenician, Greek or Etruscan, bear to their Assyrian or Egyptian models. Foremost among them are the bowls and shields from the Idaean cave in Crete. These interesting bowls are embossed with simple bands of animals, the shields with bold and complicated designs of purely oriental character. It is unlikely that a Greek craftsman in this vigorous Geometric age could suppress his style and produce mechanical copies such as these. So in Etruscan graves beside inscribed Phoenician bowls there have been found great cauldrons, adorned with jutting heads of lions and griffins, and set on conical stands which are embossed with Assyrian winged monsters.

Classical Greek and Etruscan

The bowl and stand were favourite archaic forms. The Greek stand was a fusion of the cast-rod tripod and the embossed cone. Some early examples have large triangular plates between the legs, worked in relief; but the developed type has separate legs and stays of which the joints are masked with decorative rims and feet and covering-plates. These ornaments are cast and chased, and are modelled in floral, animal and human forms. The feet are lions' paws, which sometimes clasp a ball or stands on toads; the rims and plaques bear groups of fighting animals, warriors, revelles or athletes, nymphs and satyrs, or mythological subjects in relief. Feasters recline and horsemen gallop on the rims of bowls; handles are formed by single standing figures, arched pairs of wrestlers, lovers holding hands, or two vertical soldiers carrying a horizontal comrade. Nude athletes serve as handles for all kinds of lids and vessels, draped women support mirror-disks around which love-gods fly, and similar figures crown tall shafts of candelabra. Handle-bases are modelled as satyr-masks, palmettes and sphinxes. This is Greek ornament of the 6th and later centuries. Its centres of manufacture are not precisely known, but the style of much archaic work points to Ionia.

Etruscan fabrics approach their Greek originals so closely that it is not possible to separate them in technique or design, and the Etruscan style is no more than provincial Greek. Bronze was quite plentiful in Italy, the earliest Roman coinage was of heavy bronze, and there is literary evidence that Etruscan bronzes were exported. The process of line engraving seems to have been a Latin speciality; it was applied in pictorial subjects on the backs of mirrors and on the sides large cylindrical boxes, both of which are particularly connected with Praeneste. The finest of all such boxes, the Firconi cista in the Villa Giulia at Rome, bears the signature of a Roman artist. These belong to the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. Greek mirrors of the same period are seldom engraved; the disk is usually contained in a flat box which has a repoussé design on its lid.[1]

Hellenistic and Roman

Hellenistic and Graeco-Roman forms are more conventional, and the new motives that belong to these periods are mostly floral. Busts and masks are the usual handle-plaques and spouts; heads and limbs of various animals are allotted certain decorative functions, as for instance the spirited mules' heads mentioned by Juvenal, which formed the elbow-rests of dining couches. These structural pieces are frequently inlaid with silver and niello. Bronze chairs and tables were commonly used in Hellenistic and Roman houses, and largely took the place of monumental vases that were popular in earlier days. Small household articles, such as lamps, when made of bronze are usually Roman, and a peculiarly Roman class of personal ornaments is a large bronze brooch inlaid with coloured enamels, a technique which seems to have had a Gaulish origin.

Fine art

Bronze statuettes were also made in every period of antiquity for votive use, and at least in Hellenistic and Roman times for domestic ornaments and furniture of household shrines. But the art of bronze statuary hardly existed before the introduction of hollow casting, about the middle of the 6th century BC. The most primitive votive statuettes are oxen and other animals, which evidently represent victims offered to the gods. They have been found abundantly on many temple sites. But classical art preferred the human subject, votaries holding gifts or in their ordinary guise, or gods themselves in human form. Such figures are frequently inscribed with formulas of dedication. Gods and goddesses posed conformably with their traditional characters and bearing their distinctive attributes are the most numerously represented class of later statuettes. They are a religious genre, appearing first in 4th-century sculpture and particularly favoured by Hellenistic sentiment and Roman pedantry. Many of them were doubtless votive figures, others were images in domestic shrines, and some were certainly ornaments. Among the cult-idols are the dancing Lares, who carry cornucopias and libation-bowls. The little Heracles that Lysippus made for Alexander was a table-ornament (epitrapezios): he was reclining on the lion's skin, his club in one hand, a wine-cup in the other.

Technique

With the invention of hollow casting bronze became the most important medium of monumental sculpture, largely because of its strength and lightness, which admitted poses that would not be possible in stone. But the value of the metal in later ages has involved the destruction of nearly all such statues. The few complete figures that survive, and a somewhat more numerous series of detached heads and portrait-busts, attest the excellence of ancient work in this material. The earliest statuettes are chiselled, wrought and welded; next in time come solid castings, but larger figures were composed of hammered sections, like domestic utensils, each part worked separately in repoussé and the whole assembled with rivets (σφυρήλατα). Very little of this flimsy fabric is extant, but chance has preserved one bust entire, in the Polledrara Tomb at Vulci. This belongs to the early 6th century BC, the age of repoussé work.

The process was soon superseded in such subjects by hollow casting, but beaten reliefs, the household craft from which Greek bronze work sprang, persisted in some special and highly perfected forms, as handle-plates on certain vases, emblemata on mirror-cases, and particularly as ornaments of armour, where light weight was required. The Siris bronzes in the British Museum are shoulder-pieces from a 4th-century cuirass. Casting was done by the cire perdue process in clay moulds, but a great deal of labour was spent on finishing. The casts are very finely chased, and most large pieces contain patches, inserted to make good the flaws. Heads and limbs of statues were cast separately and adjusted to the bodies: besides the evidence of literature and of the actual bronzes, there is an illustration of a dismembered statue in the making on a painted vase in Berlin.[1]

Pliny and other ancient writers have much to say in regard to various alloys of bronze — Corinthian, Delian, Aeginetan, Syracusan — in regard to their composition and uses and particularly to their colour effects, but their statements have not been confirmed by modern analyses and are sometimes manifestly false. Corinthian bronze is said to have been first produced by accident in the Roman burning of the city (146 BC) when streams of molten copper, gold and silver mingled. Similar tales are told by Plutarch and Pliny about the artists' control of colour: Silanion made a pale-faced Jocasta by mixing silver with his bronze, Aristonidas made Athamas blush with an alloy of iron. There is good evidence that Greek and Roman bronzes were not artificially patinated, though many were gilt or silvered. Plutarch admires the blue colour of some very ancient statues at Delphi, and wonders how it was produced; Pliny mentions a bitumen wash, but this was doubtless a protective lacquer; and a 4th-century inscription from Chios records the regulations made there for keeping a public statue clean and bright.[1]

European brass and bronze

This section is not concerned with sculpture in bronze, but rather with the many artistic applications of the metal in connection with architecture, or with objects for ecclesiastical and domestic use. Why bronze was preferred in Italy, iron in Spain and Germany and brass in the Low Countries cannot be satisfactorily determined; national temperamente is impressed on the choice of metals and also on the methods of working them. Centres of artistic energy shift from one place to another owing to wars, conquests or migrations.[2]

Roman and Byzantine Empires

Leaving alone remote antiquity and starting with Imperial Rome, the working of bronze, inspired probably by conquered Greece, is clearly seen. There are ancient bronze doors in the Temple of Romulus in the Roman Forum; others from the baths of Caracalla are in the Lateran Basilica, which also contains four fine gilt bronze fluted columns of the Corinthian order. The Naples Museum contains a large collection of domestic utensils of bronze, recovered from the buried towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which show a high degree of perfection in the working of the metal, as well as a wide application of its use. A number of moorings in the form of finely modelled animal heads, made in the 1st century AD, and recovered from Lake Nemi in the Alban hills some years ago, show a further acquaintance with the skilful working of this metal. The throne of Dagobert in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, appears to be a Roman bronze curule chair, with back and part of the arms added by the Abbot Suger in the 12th century.

Byzantium, from the time when Constantine made it the seat of empire, in the early part of the 4th century, was for 1,000 years renowned for its works in metal. Its position as a trade centre between East and West attracted all the finest work provided by the artistic skills of craftsmen from Syria, Egypt, Persia, Asia Minor and the northern shores of the Black Sea, and for 400 years, until the beginning of the Iconoclastic period in the first half of the 8th century, its output was enormous. Several Italian churches still retain bronze doors cast in Constantinople in the later days of the Eastern Empire, such as those presented by the members of the Pantaleone family, in the latter half of the 11th century, to the churches at Amalfi, Monte Cassino, Atrani and Monte Gargano. Similar doors are at Salerno; and St Mark's, Venice, also has doors of Greek origin.

Germany

.JPG.webp)

The period of the iconoclasts synchronised with the reign of the Frankish emperor Charlemagne, whose power was felt throughout western Europe. Some of the craftsmen who were forced to leave Byzantium were welcomed by him in his capitals of Cologne and Aix-la-Chapelle and their influence was also felt in France. Another stream passed by way of the Mediterranean to Italy, where the old classical art had decayed owing to the many national calamities, and here it brought about a revival. In the Rhineland and elsewhere in Europe the terms "Rhenish-Byzantine" and "Romanesque" applied to architecture and works of art generally, testify to the provenance of the style of this and the succeeding period. The bronze parapet of Aachen Cathedral is of classic design and probably dates from Charlemagne's time.

All through the Middle Ages the use of bronze continued on a great scale, particularly in the 11th and 12th centuries. Bernward, bishop of Hildesheim, a great patron of the arts, had bronze doors, the Bernward Doors, made for St Nicholas' church (afterwards removed to the cathedral) which were set up in 1015; great doors were made for Augsburg somewhere between 1060 and 1065, and for Mainz[3] shortly after the year 1000. A prominent feature on several of these doors is seen in finely modelled lion jaws, with conventional manes and with ring hanging from their jaws. These have their counterpart in France and Scandinavia as well as in England, where they are represented by the so-called Sanctuary Knocker at Durham Cathedral.[4]

Provision of elaborate tomb monuments and church furniture gave much work to German and Netherlandish founders. Mention may be made of the seven-branch candlestick at Essen Cathedral made for the Abbess Matilda about the year 1000, and another at Brunswick completed in 1223; also of the remarkable font of the 13th century made for Hildesheim Cathedral at the charge of Wilbernus, a canon of the cathedral. Other fonts are found at Brandenburg and Würzburg. Vast numbers of bronze and brass ewers, holy-water vessels, reliquaries and candelabra were produced in the Middle Ages. In general, most of the finest work was executed for the Church.[2] An important centre of medieval copper and brass casting (Dutch: geelgieten; literally "yellow casting") was the Meuse Valley, especially in the 12th century. The city of Dinant gave its name to the French term for all types of artistic copper and brass work: dinanderie (see also section "Brass"). After the destruction of the town by Charles the Bold in 1466, many brass workers moved to Maastricht, Aachen and other towns in Germany and even England.

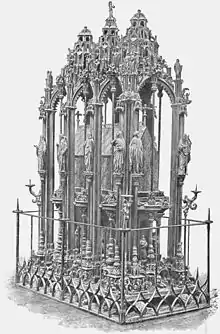

The end of the Gothic period saw some great craftsmen in Germany and the Habsburg Netherlands. The brass worker Aert van Tricht was based in Maastricht but worked in St. John's Cathedral, 's-Hertogenbosch and Xanten Cathedral. A bronze lectern for St. Peter's Church, Leuven is now in the collection of The Cloisters in New York. Peter Vischer of Nuremberg, and his sons, working on the bronze reliquary of Saint Sebald, a finely conceived monument of architectural form, with rich details of ornament and figures; among the latter appearing the artist in his working dress. The shrine was completed and set up in the year 1516. This great craftsman executed other fine works at Magdeburg, Römhild and Breslau. Reference should be made to the colossal monument at Innsbruck, the tomb of the Emperor Maximilian I, with its 28 bronze statues of more than life size. Large fountains in which bronze was freely employed were set up, such as those at Munich and Augsburg. The tendency was to use this metal for large works of an architectural or sculpturesque nature; while at the same time smaller objects were produced for domestic purposes.[2] By the late 15th to 16th centuries, a style of ornamental brass bowls called Beckenschlägerschüssel had developed.

Italy

By the 12th century the Italian craftsmen had developed a style of their own, as may be seen in the bronze doors of Saint Zeno, Verona (which are made of hammered and not cast bronze), Ravello, Trani and Monreale. Bonanno da Pisa made a series of doors for the duomo of that city, one pair of which remains. The 14th century witnessed the birth of a great revival in the working of bronze, which was destined to flourish for at least four centuries. Bronze was a metal beloved of the Italian craftsman; in that metal he produced objects for every conceivable purpose, great or small, from a door-knob to the mighty doors by Lorenzo Ghiberti at Florence, of which Michelangelo remarked that they would stand well at the gates of Paradise. Nicola, Giovanni and Andrea Pisano, Ghiberti, Brunelleschi, Donatello, Verrocchio, Cellini, Michelangelo, Giovanni da Bologna — these and many others produced great works in bronze.

Benedetto da Rovezzano came to England in 1524 to execute a tomb for Cardinal Wosley, part of which, after many vicissitudes, is now in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral. Pietro Torrigiano of Florence executed the tomb of Henry VII in Westminster Abbey. Alessandro Leopardi, at the beginning of the 16th century, completed the three admirable sockets for flag-staffs which still adorn the Piazza San Marco, Venice. A further development showed itself in the production of portrait medals in bronze, which reached a high degree of perfection and engaged the attention of many celebrated artists. Bronze plaquettes for the decoration of large objects exhibit a fine sense of design and composition. Of smaller objects, for church and domestic use, the number was legion. Among the former may be mentioned crucifixes, shrines, altar and paschal candlesticks, such as the elaborate examples at the Certosa of Pavia; for secular use, mortars, inkstands, candlesticks and a large number of splendid door-knockers and handles, all executed with consummate skill and perfection of finish. Work of this kind continued to be made throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.[2]

France

The Candelabro Trivulzio in the Milan Cathedral, a seven-branch bronze candlestick measuring 5 meters in height, has a base and lower part decorated with intricately designed ornament which is considered by many to be French work of the 13th century; the upper part with the branches was added in the second half of the 16th century. A portion of a similar object showing the same intricate decoration existed formerly at Reims, but was unfortunately destroyed during World War I.

In the 16th century the names of Germain Pilon and Jean Goujon are sufficient evidence of the ability to work in bronze. A great outburst of artistic energy is seen from the beginning of the 17th century, when works in ormolu or gilt bronze were produced in huge quantities. The craftsmanship is magnificent and of the highest quality, the designs at first refined and symmetrical; but later, under the influence of the rococo style, introduced in 1723, aiming only at gorgeous magnificence. It was all in keeping with the spirit of the age, and in their own sumptuous setting these fine candelabra, sconces, vases, clocks and rich mountings of furniture are entirely harmonious. The "ciseleur" and the "fondeur", such as Pierre Gouthière and Jacques Caffieri, associated themselves with the makers of fine furniture and of delicate Sèvres porcelain, the result being extreme richness and handsome effect. The style was succeeded after the French Revolution by a stiff, classical manner which, although having a charm of its own, lacks the life and freedom of earlier work. In London the styles may be studied in the Wallace collection, Manchester Square, and at the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington; in New York at the Metropolitan Museum.[2]

England

Casting in bronze reached high perfection in England, where a number of monuments yet remain. William Torel, goldsmith and citizen of London, made a bronze effigy of Henry III, and later that of Queen Eleanor for their tombs in Westminster Abbey; the effigy of Edward III was probably the work of one of his pupils. No bronze fonts are found in English churches, but a number of processional crucifixes have survived from the 15th century, all following the same design and of crude execution. Sanctuary rings or knockers exist at Norwich, Gloucester and elsewhere; the most remarkable is that on the north door of the nave of Durham Cathedral which has sufficient character of its own to differentiate it from its Continental brothers and to suggest a Northern origin.

The Gloucester Candlestick in the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington, displays the power and imagination of the designer as well as an extraordinary manipulative skill on the part of the founder.[5] According to an inscription on the object, this candlestick, which stands some 2 ft (61 cm) high and is made of an alloy allied to bronze, was made for Abbot Peter who ruled from 1109 to 1112. While the outline is carefully preserved, the ornament consists of a mass of figures of monsters, birds and men, mixed and intertwined to the verge of confusion. As a piece of casting it is a triumph of technical ability.[5] For secular use the mortar was one of the commonest of objects in England as on the Continent; early examples of Gothic design are of great beauty. In later examples a mixture of styles is found in the bands of Gothic and Renaissance ornament, which are freely used in combination. Bronze ewers must have been common; of the more ornate kind two may be seen, one at South Kensington and a second at the British Museum. These are large vessels of about 2 ft (61 cm) in height, with shields of arms and inscriptions in bell-founders' lettering. Many objects for domestic use, such as mortars, skillets, etc., were produced in later centuries.[1][2]

Bells

In northern Europe, France, Germany, England and the Netherlands, bellfounding has been an enormous industry since the early part of the Middle Ages. Unfortunately a large number of medieval bells have been melted down and recast, and in times of warfare many were seized to be cast into guns. Early bells are of graceful outline, and often have simple but well-designed ornaments and very decorative inscriptions; for the latter a separate stamp or die was used for each letter or for a short group of letters. In every country bell-founders were an important group of the community; in England a great many of their names are known and the special character of their work is recognizable. Old bells exist in the French cathedrals of Amiens, Beauvais, Chartres and elsewhere; in Germany at Erfurt, Cologne and Halberstadt. The bell-founding industry has continued all through the centuries, one of its later achievements being the casting of "Big Ben" at Westminster in 1858, a bell of between 13 and 14 tons in weight.[1][2]

In more recent years, bronze has to some extent replaced iron for railings, balconies and staircases, in connection with architecture; the style adopted is stiffly classical, which does not call for a very large amount of ornamentation, and the metal has the merit of pleasant appearance and considerable durability.

Brass

Brass is an alloy composed of copper and zinc, usually for sheet metal, and casting in the proportion of seven parts of the former to three of the latter. Such a combination secures a good, brilliant colour. There are, however, varieties of tone ranging from a pale lemon colour to a deep golden brown, which depends upon a smaller or greater amount of zinc. In early times this metal seems to have been sparingly employed, but from the Middle Ages onward the industry in brass was a very important one, carried out on a vast scale and applied in widely different directions. The term "latten", which is frequently met with in old documents, is rather loosely employed, and is sometimes used for objects made of bronze; its true application is to the alloy we call brass. In Europe its use for artistic purposes centered largely in the region of the Meuse valley in south-east Belgium, together with north-eastern France, parts of the Netherlands and the Rhenish provinces of which Cologne was the center.

As far back as the 11th century the inhabitants of the town of Huy and Dinant are found working this metal; zinc they found in their own country, while for copper they went to Cologne or Dortmund, and later to the mines of the Harz Mountains. Much work was produced both by casting and repoussé, but it was in the former process that they excelled. Within a very short time the term "dinanderie" was coined to designate the work in brass which emanated from the foundries of Dinant and other towns in the neighbourhood. Their productions found their way to France, Spain, England and Germany. In London the Dinant merchants, encouraged by Edward III, established a "Hall" in 1329 which existed until the end of the 16th century; in France they traded at Rouen, Calais, Paris and elsewhere. The industry flourished for several centuries, but was weakened by quarrels with their rivals at the neighboring town of Bouvignes; in 1466 the town was sacked and destroyed by Charles the Bold. The brass-founders fled to Huy, Namur, Middleburg, Tournai and Bruges, where their work was continued.[1][2]

The earliest piece of work in brass from the Meuse district is the baptismal font at St Bartholomew's Church, Liège (cf. Fig. 1 in Gallery), a large vessel resting on oxen, the outside of the bowl cast in high relief with groups of figures engaged in baptismal ceremonies; it was executed between 1113 and 1118 by Renier of Huy, the maker of a notable censer in the museum of Lille.

From this time onward a long series of exceptional works were executed for churches and cathedrals in the form of fonts, lecterns, paschal and altar candlesticks, tabernacles and chandeliers; fonts of simple outline have rich covers frequently adorned with figure subjects; lecterns are usually surmounted by an eagle of conventional form, but sometimes by a pelican (cf. Fig. 2); a griffin surmounts the lectern at Andenne. The stands which support these birds are sometimes of rich Gothic tracery work, with figures, and rest upon lions; later forms show a shaft of cylindrical form, with mouldings at intervals, and splayed out to a wide base. A number are found in Germany in the Cologne district, which may be of local manufacture; some remain in Venice churches. About a score have been noted in English churches, as at Norwich, St Albans, Croydon and elsewhere. For the most part they follow the same model, and were probably imported from Belgium. Fine brass chandeliers exist, at the Temple Church, Bristol (cf. Fig. 3), at St Michael's Mount, Cornwall, and in North Wales. The lecterns must have set the fashion in England for this type of object; for several centuries they are found, as at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, King's College Chapel, Cambridge, St Paul's Cathedral and some London churches (cf. Fig. 4). In the region of Cologne much brass-work was produced and still remains in the churches; mention must be made of the handsome screen in the Xanten Cathedral, the work, it is said, of a craftsman of Maastricht, the Netherlands, at the beginning of the 16th century. A modern example is the Hereford Screen in the Hereford Cathedral, made by George Gilbert Scott in 1862 in a variety of metals where brass dominates (cf. Fig. 5)

The Netherlands, Norway and Sweden also produced chandeliers, many of great size: the 16th- and 17th-century type is the well known "spider", large numbers of which were also made in England and still hang in many London and provincial churches. The Netherlands also showed a great liking for hammered work, and produced a large number of lecterns, altar candlesticks and the like in that method. The large dishes embossed with Adam and Eve and similar subjects are probably of Dutch origin, and found in neighbouring countries. These differ considerably from the brass dishes in which the central subject – the Annunciation, St George, St Christopher, the Agnus Dei, a mermaid or flowers – is surrounded by a band of letters, which frequently have no significance beyond that of ornamentation; the rims are stamped with a repeating pattern of small designs. This latter type of dish was probably the work of Nuremberg or Augsburg craftsmen, and it should be noticed that the whole of the ornament is produced by hammering into dies or by use of stamps; they are purely mechanical pieces.

Brass was widely used for smaller objects in churches and for domestic use. Flemish and German pictures show candlesticks, holy water stoups, reflectors, censers and vessels for washing the hands as used in churches. The inventories of Church goods in England made the time of the Reformation disclose a very large number of objects in latten which were probably made in the country. In general use was an attractive vessel known as the aquamanile (cf. Fig. 6); this is a water-vessel usually in the form of a standing lion, with a spout projecting from his mouth; on the top of the head is an opening for filling the vessel, and a lizard-shaped handle joins the back of the head with the tail. Others are in the form of a horse or ram; a few are in the form of a human bust, and some represent a mounted warrior. They were produced from the 12th to the 15th centuries. Countless are the domestic objects: mortars, small candlesticks, warming pans, trivets, fenders; these date mainly from the 17th and 18th centuries, when brass ornamentation was also frequently applied to clockdials, large and small. Two English developments during the 17th century call for special notice. The first was an attempt to use enamel with brass, a difficult matter, as brass is a bad medium for enamel.

A number of objects exist in the form of firedogs, candlesticks, caskets, plaques and vases, the body of which is of brass roughly cast with a design in relief; the hollow spaces between the lines of the design are filled in with patches of white, black, blue or red enamel, with very pleasing results (cf. Fig. 7). The nearest analogy is found in the small enamelled brass plaques and icons produced in Russia in the 17th and 18th centuries. The second use of brass is found in a group of locks of intricate mechanism, the cases of which are of brass cast in openwork with a delicate pattern of scroll work and bird forms sometimes engraved. A further development shows solid brass cases covered with richly engraved designs (cf. Fig. 8). The Victoria and Albert Museum of London, contains a fine group of these locks; others are in situ at Hampton Court Palace and in country mansions.[1][2]

During the 18th century brass was largely used in the production of objects for domestic use; the manufacture of large hanging chandeliers also continued, together with wall-sconces and other lighting apparatus. In the latter half of the 19th century there came an increasing demand for ecclesiastical work in England; lecterns, alms dishes, processional crosses and altar furniture were made of brass; the designs were for the greater part adaptations of older work and without any great originality.

Monumental brasses

The working of memorial brasses is generally considered to have originated in north-western Germany, at least one centre being Cologne, where were manufactured the latten or Cullen plates for local use and for exportation. But it is certain that from medieval times there was an equal production in the towns of Belgium, when brass was the favoured metal for other purposes. Continental brasses were of rectangular sheets of metal on which the figure of the deceased was represented, up to life-size, by deeply incised lines, frequently filled with mastic or enamel-like substance; the background of the figures was covered with an architectural setting, or with ornament of foliage and figures, and an inscription. In England, possibly because the metal was less plentiful, the figures are usually accessories, being cut out of the metal and inserted in the matrices of stone or marble slabs which form part of the tomb; architectural canopies, inscriptions and shields of arms are affixed in the same way. Thus the stone or marble background takes the place of the decorated brass background of the Continental example. The early method of filling in the incisions has suggested some connection with the methods of the Limoges enamellers of the 13th century. The art was introduced into England from the Low Countries, and speedily attained a high degree of excellence. For many centuries it remained very popular, and a large number of brasses still remain to witness to a very beautiful department of artistic working.[2]

The earliest existing brass is that of Bishop Ysowilpe at Verden, in Germany, which dates from 1231 and is on the model of an incised stone, as if by an artist accustomed to work in that material. In England the oldest example is at Stoke D'Abernon church, in Surrey, to the memory of Sir John D'Abernon, who died in 1277. Numerous brasses are to be found in Belgium, and some in France and the Netherlands. Apart from their artistic attractiveness, these ornamental brasses are of the utmost value in faithfully depicting the costumes of the period, ecclesiastical, civil or military; they furnish also appropriate inscriptions in beautiful lettering (cf. Brass Gallery).[1][2]

South Asia

Excavations from sites where Indus Valley civilisation once flourished reveal usage of bronze for various purposes. Earliest known usage of bronze for art form can be traced back to 2500 BC. Dancing Girl of Mohenjo Daro is attributed for the same. Archaeologists working on excavation site at Kosambi in Uttar Pradesh unearthed a bronze figure of a Girl riding two bulls which is dated approximately between 2000 - 1750 BC further reveals the usage of bronze for casting into an art form during the Late Harappan period. Another such instance of a Late Harappan period bronze artifact was found at Daimbad in Maharashtra suggesting a possibility of a more widespread usage of bronze then localised to places around Indus Valley alone.

Bronze continued to be used as a metal for various statues and statuettes during Classical Period as can be seen from the Bronze hoard discovered in Chausa Bihar, which consisted of bronze statuettes dating between 2nd BC to 6th Century AD.

Bronze art picked up in South India during the Middle Ages during the rule of Pallava's, 8th Century Ardhaparyanka asana icon of Shiva is one notable artifact from this period. Bronze sculpting however peaked during the reign of Cholas (c. 850 CE - 1250 CE). Many of the bronze sculptures from this period are now present in various museums around the world. Nataraja statue found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City is a remarkable piece of sculpting from this period.

Brass gallery

Fig. 1 – The Liège font by Renier of Huy

Fig. 1 – The Liège font by Renier of Huy Fig. 2 – Lectern surmounted by a pelican (symbol of Christ), Church of Saint-Julien-Chapteuil

Fig. 2 – Lectern surmounted by a pelican (symbol of Christ), Church of Saint-Julien-Chapteuil Fig. 3 – Brass Chandelier in the Temple Church, Bristol

Fig. 3 – Brass Chandelier in the Temple Church, Bristol Fig. 4 – Lectern at St Mary, Lansdowne Road, London

Fig. 4 – Lectern at St Mary, Lansdowne Road, London Fig. 5 – The Hereford Screen, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and made of wrought and cast iron, brass, copper, semi-precious stones, and mosaics

Fig. 5 – The Hereford Screen, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and made of wrought and cast iron, brass, copper, semi-precious stones, and mosaics Fig. 6 – Brass aquamanile from Lower Saxony, Germany, c. 1250

Fig. 6 – Brass aquamanile from Lower Saxony, Germany, c. 1250 Fig. 7 – Casket with Scenes of Ancient Lion Hunts, gilt on painted enamel, gilded brass by French enamelist Pierre Reymond

Fig. 7 – Casket with Scenes of Ancient Lion Hunts, gilt on painted enamel, gilded brass by French enamelist Pierre Reymond Fig. 8 – Reliquary casket with combination lock made of gilded brass with Arab letters, ca. 1200. Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius, Maastricht

Fig. 8 – Reliquary casket with combination lock made of gilded brass with Arab letters, ca. 1200. Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius, Maastricht

Memorial brass of the Swift family, 16th century, All Saints Church, Rotherham, later owners of Broom Hall, Sheffield

Memorial brass of the Swift family, 16th century, All Saints Church, Rotherham, later owners of Broom Hall, Sheffield Monumental brass grave plate for bishops Ludolf (d. 1339) and Heinrich (d. 1347) von Bülow in the Schwerin Cathedral

Monumental brass grave plate for bishops Ludolf (d. 1339) and Heinrich (d. 1347) von Bülow in the Schwerin Cathedral

See also

References

- This article is mainly based on specialised literature from the following sources: 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica – especially the information s.v. "Metallic Ornamental Work" written by William Walter Watts, with relevant bibliography; H.W. Macklin, Monumental Bronzes, 1913 and Monumental Brasses, ed. J. P. Phillips, London (repr. 1969); Paris, Musée des Arts décoratifs, Le Métal, 1939; "Antiquaries and Historians: The Study of Monuments", OUP, retrieved 28 March 2013; M. W. Norris, Monumental Brasses: The Memorials, 2 vols., London, 1977; idem, Monumental Brasses: The Craft, London, 1978; F. Haskell, History and its Images: Art and the Interpretation of the Past, New Haven and London, 1993, pp. 131–5.

- For this section cf. free text from the following publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition. Cambridge University Press – and article reproduction at Archived 3 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- The Market Portal of the Mainz Cathedral. The huge bronze gates were cast on behalf of Archbishop Willigis. Archbishop Adalbert of Mainz ordered the engraving of the city rights in the upper part in 1135.

- John MacLean, ed. (1889–1890). "Sanctuary Knockers". Transactions - Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. Bristol: C. T. Jefferies and Sons, Limited. pp. 131–140. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "The Gloucester Candlestick, decoration". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

Bibliography

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Metal-Work". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 205–215.

- Bayley, J. (1990) "The Production of Brass in Antiquity with Particular Reference to Roman Britain" in Craddock, P.T. (ed.) 2000 Years of Zinc and Brass London: British Museum

- Craddock, P.T. and Eckstein, K (2003) "Production of Brass in Antiquity by Direct Reduction" in Craddock, P.T. and Lang, J. (eds) Mining and Metal Production Through the Ages London: British Museum

- Day, J. (1990) "Brass and Zinc in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 19th century" in Craddock, P.T. (ed.) 2000 Years of Zinc and Brass London: British Museum

- Day, J (1991) "Copper, Zinc and Brass Production" in Day, J and Tylecote, R.F (eds) The Industrial Revolution in Metals London: The Institute of Metals

- Martinon Torres, M. & Rehren, T. (2002). Historical Metallurgy. 36 (2): 95–111.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Rehren, T. and Martinon Torres, M. (2008) "Naturam ars imitate: European brassmaking between craft and science" in Martinon-Torres, M and Rehren, T. (eds) Archaeology, History and Science Integrating Approaches to Ancient Material: Left Coast Press

- Scott, David A. (2002). Copper and bronze in art: corrosion, colorants, conservation. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-638-5.

External links

- "Lost Wax, Found Bronze": lost-wax casting explained

- "Flash animation of the lost-wax casting process". James Peniston Sculpture. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- Viking Bronze – Ancient and Early Medieval bronze casting

- Bronze bells

- Brass.org

- Monumental Brass Society

- European sculpture and metalwork, a collection catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on bronze and brass ornamental work