Welsh art

Welsh art is the traditions in the visual arts associated with Wales and its people. Most art found in, or connected with, Wales is essentially a regional variant of the forms and styles of the rest of the British Isles, a very different situation from that of Welsh literature. The term Art in Wales is often used in the absence of a clear sense of what "Welsh art" is, and to include the very large body of work, especially in landscape art, produced by non-Welsh artists in Wales (or with a Welsh subject) since the later 18th century.[1]

.jpeg.webp)

Early history

Prehistoric Wales has left a number of significant finds: Kendrick's Cave, Llandudno contained the Kendrick's Cave Decorated Horse Jaw, "a decorated horse jaw which is not only the oldest known work of art from Wales but also unique among finds of Ice Age art from Europe", and is now in the British Museum.[2] In 2011 "faint scratchings of a speared reindeer" were found on a cave wall on the Gower peninsula which probably date to 12,000–14,000 BC, placing them among the earliest art found in Britain.[3] The Mold Gold Cape, also in the British Museum, and Banc Ty'nddôl sun-disc in the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff are likewise some of the most important British works of art from the Bronze Age.

Many works of Iron Age Celtic art have been found in Wales.[4] and the finds from the period shortly before and after the Roman conquest, which reached Wales in AD 74-8, are especially significant. Pieces of metalwork from Llyn Cerrig Bach on Anglesey and other sites exemplify the final stages of La Tène style in the British Isles, and the Capel Garmon Firedog is a spectacular luxury piece of ironwork, among the finest in Europe from the period.[5] The Abergavenny Leopard Cup, from the decades after the conquest, was found in 2003, and shows the presence of imported Roman luxury products in Wales, perhaps belonging to a soldier.[6]

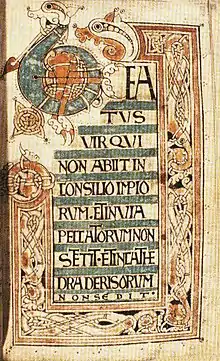

In the Early Medieval period, the Celtic Christianity of Wales participated in the Insular art of the British Isles and a number of illuminated manuscripts possibly of Welsh origin survive, of which the 8th century Hereford Gospels and Lichfield Gospels are the most notable. The 11th century Ricemarch Psalter (now in Dublin) is certainly Welsh, made in St David's, and shows a late Insular style with unusual Viking influence, which is also seen in surviving pieces of metalwork of that period.

There are only fragments of the architecture of the period remaining. Unlike Irish high cross and Pictish stones, early Welsh standing stones mainly employ geometric patterns and words, rather than figure representation; however, 10th century stones represent Christ and various saints. Little metalwork survives from the early period of the 5th–9th centuries in Wales. However, archaeological sites at Dinas Powys have revealed various artifacts such as penannular brooches and other pieces of jewellery. Similar brooches have been discovered a site at Penycorddyn-mawr, near Abergele, dating to the 8th century. During this period, the construction of Holy wells was also particularly commonplace in Wales.

Wales has rarely been very prosperous, and the most striking medieval architecture is military, often built by the Normans and English, especially the famous "Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd" and Beaumaris Castle in Anglesey, recognised as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Caerphilly Castle and the castles of the Welsh Prince Llywelyn the Great (such as Criccieth Castle and Dolbadarn Castle). There are a number of impressive monastic ruins; Welsh medieval churches are nearly all relatively modest, including the cathedrals. They very often had wall-paintings, panel altarpieces and much other religious art, but as in the rest of Britain very little has survived. Conwy, an English garrison town with its medieval walls almost entirely intact, has a notable example of a 13th-century medieval stone town-house.

The Renaissance in Wales

Peter Lord suggests that the Renaissance began in Wales around 1400.[7] Much of the art produced in this period was created in or for the church. Strata Florida Abbey, for example, retains some of its medieval decorated tiles.[8]

Despite the widespread destruction that took place during the Reformation and later the Commonwealth, a number of Welsh churches retain fragments of medieval stained glass. These include All Saints' Church, Gresford, St Michael's Church, Caerwys, St Mary's Church, Treuddyn, St Elidan's Church, Llanelidan, Church of St Mary & St Nicholas, Beaumaris, St Gwyddelan's Church, Dolwyddelan, and St David's Cathedral.[9]

Fifteenth-century wall paintings have been uncovered in several Welsh church buildings, including St Cadoc's Church, Llancarfan,[10] St Illtyd's Church, Llantwit Major (which has a painting of Saint Christopher believed to date from around 1400),[11] and St Teilo's Church, Llandeilo Tal-y-bont. The latter, during its reconstruction at St Fagans National History Museum during the 1990s, was found to contain wall paintings from several different periods, the earliest estimated as being from the first half of the fifteenth century.[12] The wall paintings at Llancarfan are said to be "beyond compare in Wales".[13]

Plas Mawr, a grand Elizabethan town-house in Conwy, built by Robert Wynn, a local man who had been English ambassador to the Holy Roman Emperor, has been extensively restored by Cadw, both inside and out, to reflect its appearance when built in the second half of the sixteenth century.[14] Wales has numerous country houses from all periods after the Elizabethan, many still containing good portraits, but these were mostly painted in London or on the Continent.[15]

Portraiture

Within Wales, portraiture is not common in the medieval and post-medieval periods, and the Welsh nobility and gentry usually went to London or other English centres to have their portraits painted; many of these remain in Welsh collections. Katheryn of Berain,[16] who claimed Tudor ancestry and earned the nickname "Mam Gymru" ("Mother of Wales") because of her network of relationships and descendants from four marriages, was painted by Adriaen van Cronenburgh, a Dutch painter. The portrait was commissioned by her husband, Sir Richard Clough, a merchant whose business caused the couple to settle briefly in Antwerp. Clough himself died before he could bring his wife to the new house he had built for her. Plas Clough, near his home town of Denbigh, includes a Flemish-style crow-stepped gable[17] The arms of the Holy Sepulchre (Clough had been made a Knight of the Holy Sepulchre earlier in his career) are painted on a plaque, but there are no surviving contemporary portraits of Clough himself.

William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke (died 1570), was one of the first Welsh nobles known to have collected paintings on a large scale. A portrait of him, dating from the 1560s, is held by the National Museum of Wales; it is attributed to Steven van Harwijck, another Dutch artist.[18]

Later, artisan painters such as William Roos and Hugh Hughes began to seek portrait commissions.[19] Roos's 1835 portrait of preacher Christmas Evans is held by the National Museum of Wales, as is Hughes' 1826 portrait of William Jenkins Rees.[20]

Landscapes

The best of the few Welsh artists of the 16th to 18th centuries tended to move elsewhere to work, but in the 18th century the dominance of landscape art in English art brought them motives to stay at home, and brought an influx of artists from outside to paint Welsh scenery, which was "discovered" by artists rather earlier than later landscape hotspots like the English Lake District and the Scottish Highlands. The Welsh painter Richard Wilson (1714–1782) is arguably the first major British landscapist, but rather more notable for Italian scenes than Welsh ones, although he did paint several on visits from London.

Wilson's pupil Thomas Jones (1742–1803), has a rather higher status today than in his own time, but mainly for his city scenes painted in Italy, though his The Bard (1774, Cardiff) is a classic work showing the emerging combination of the Celtic Revival and Romanticism.[21] He returned to live in Wales on inheriting the family estate, but largely stopped painting. For most visiting artists the main attraction was dramatic mountain scenery, in the new taste for the sublime partly stimulated by Edmund Burke's A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), though some earlier works were painted in Wales in this strain.[22] Early works tended to see the Welsh mountains through the prism of the 17th century Italianate "wild" landscapes of Salvator Rosa and Gaspard Dughet.[23]

By the 1770s a number of guide books had been published, including Joseph Cradock's Letters from Snowdon (1770) and An Account of Some of the Most Romantic Parts of North Wales (1777). Thomas Pennant wrote Tour in Wales (1778) and Journey to Snowdon (1781/1783); though Welsh himself, Pennant had published a Tour in Scotland first, in 1769.[24] The first of a series of British tours by another leading promoter of the picturesque, William Gilpin, was Observations on the River Wye and several parts of South Wales, etc. relative chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the summer of the year 1770, but not published until 1782. Paul Sandby made his first recorded visit to Wales in 1770, later (1773) touring south Wales with Sir Joseph Banks, resulting in the 1775 publication of XII Views in South Wales and a further 12 views the following year, part of a 48-plate series of aquatints of Welsh views commissioned by Banks. This was an early example of many print series and illustrated books on Wales, often as valuable in terms of income to the artists as original works.

What might fifty years earlier have been merely regarded as inconvenience in travel could now be seen as an exciting adventure worth making the subject of a painting, as in Julius Caesar Ibbetson's Phaeton in a Thunderstorm (1798, now Temple Newsam, Leeds) which shows a carriage struggling up a rough mountain road. It has a label on the back by the artist, recording that the incident occurred when he was travelling in Wales with the artist John "Warwick" Smith and the aristocrat Robert Fulke Greville.[25] Ibbetson visited Wales often, and was also one of the first artists to record the Welsh Industrial Revolution, and scenes of Welsh life.

North Wales tended to be more visited; the young watercolourist John Sell Cotman embarked on his "first extended sketching tour" in 1800, starting from Bristol then following "a well-trodden path into the Wye Valley, through Brecknockshire to Llandovery and north to Aberystwyth. In Conway he joined a group of artists gathered around the amateur Sir George Beaumont" perhaps meeting Thomas Girtin there, and continuing to Caernarvon and Llangollen. A second trip followed in 1802; he continued to use motifs from his sketches throughout his career.[26] Other artists often in Wales in this period included Francis Towne, the brothers Cornelius and John Varley and John's pupils Copley Fielding and David Cox (for whose lifelong attachment to Wales see below). Even the caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson visited with Henry Wigstead, a colleague, and they published Remarks on a Tour to North and South Wales, in the Year 1797, an illustrated book.[27][28]

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars made continental travel impossible for long periods, increasing the visitors to Wales and other parts of Britain. The young J. M. W. Turner made his first extended tour to South and mid-Wales in 1792, followed by North Wales in 1794, and a seven-week tour of Wales in 1798. He also visited Yorkshire and Scotland in the 1790s, but was unable to visit Europe until after the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, when he reached the Alps; he did not visit Italy until 1819.[29] Many of his key early works drew on his Welsh travels, although they were painted back in London. His "first large classicising watercolour, a Claudeian view of Caernarvon Castle at sunset" was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1799, along with an oil of the same subject, and the next year he showed another view of the castle, this time with small foreground figures of "a bard singing to his followers of the destruction of Welsh civilization by the invading armies of Edward I", another Claudeian formula that he was to repeat many times in major works for the rest of his career, and was arguably the first large "exhibition watercolour", reaching into the realm of history painting.[30]

Expansion

It remained difficult for artists relying on the Welsh market to support themselves until well into the 20th century. The 1851 census records only 136 people describing their occupation as "artist" out of a population of 945,000, with a further 50 engaged in fine arts-related occupations such as engraving.[31] An Act of Parliament in 1857 provided for the establishment of a number of art schools throughout the United Kingdom, and the Cardiff School of Art opened in 1865. Prior to that the annual report for 1855 of the government Science and Art Department shows a list of the larger type of Art School in many British cities, but none in Wales.[32] Under a recently introduced new system "Local Schools of Art" had been established in 1853 in Llanelly and Merthyr, but had already closed; those in Swansea and Carmarthen continued, and Flint had applied to establish a school. There were "Drawing Schools" in Aberdare and Bangor, but apparently nothing at all in Cardiff.[33] However all these pre-1857 schools, except perhaps Swansea, were mainly teaching school age children, usually in their normal schools, and training in industrial design or teacher-training under the elementary stages of the "South Kensington system".[34]

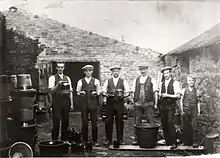

Graduates of the new fine arts Welsh colleges still very often had to leave Wales to work. Established artists continued to move in the opposite direction, at least for the summer. David Cox was an English 19th century landscapist who spent much time in Wales, for many years spending the summer based in Betws-y-Coed, a popular centre for artists, including the English Henry Clarence Whaite and the German Hubert von Herkomer, one of whose wives was Welsh. Landscape continued to be the main focus, although the Welsh artist Charles William Mansel Lewis was among those who painted common working people, with varying measures of realism or picturesqueness. The "Betws-y-Coed artist's colony" was one of the groups forming the Royal Cambrian Academy of Art in 1881; this was always a group for exhibiting rather than a teaching institution, based in Conwy, until 1994 in Plas Mawr (see above).

[35] The sculptors John Evan Thomas (1810–1873) and Sir William Goscombe John (1860–1952) made many works for Welsh commissions, although they had settled in London. Even Christopher Williams (1873–1934), whose subjects were mostly resolutely Welsh, was based in London. Thomas E. Stephens (1886–1966) and Andrew Vicari (b. 1938) had very successful careers as portraitists based respectively in the United States and France. Sir Frank Brangwyn was Welsh by origin, but spent little time in Wales.

Perhaps the most famous Welsh-born painters were Augustus John and his sister Gwen John, though they mostly lived in London and Paris; however the landscapists Sir Kyffin Williams (1918–2006) and Peter Prendergast (1946–2007) remained living in Wales for most of their lives, though well in touch with the wider art world. Ceri Richards was very engaged in the Welsh art scene as a teacher in Cardiff, and even after moving to London; he was a figurative painter in international styles including Surrealism. Various artists have moved to Wales, usually the countryside, though paintings of Cardiff of around 1893–97 by the American artist Lionel Walden are in museums in Cardiff and Paris.[36] These included Eric Gill, whose colony included for his most artistically productive period (1924–1927) the London-born Welshman David Jones, and the sculptor Jonah Jones. The Kardomah Gang was an intellectual circle centred on the poet Dylan Thomas and poet and artist Vernon Watkins in Swansea, which also included the painter Alfred Janes; the eponymous cafe was destroyed by a German bomb in 1941.

The situation gradually improved after World War II, with the appearance of new art groups. The South Wales Group was established in 1948 (and continues today as The Welsh Group with membership from across Wales).[37][38][39][40] The group's initial conception was in response to the Royal Cambrian Academy's relatively weak representation from south Wales at the time. In 1956 when the South Wales Group failed to become a southern Academy, the 56 Group Wales also emerged,[41] with the aim of promoting modern Welsh art beyond Wales' borders.[42] Also in the industrial valleys the Dowlais Settlement, delivering art classes and activities was established in the 1940s by artists including Heinz Koppel and Arthur Giardelli and the Rhondda Group was formed in the 1950s, a loose group of art students whose most notable member was Ernest Zobole, whose expressionist work was deeply rooted in the juxtaposition of the industrialised buildings of the valleys set against the green hills that surround them.[43] In the 1970s, Paul Davies formed Beca, a radical Welsh group whose founding was in part a reaction to the drowning of Capel Celyn.[44] Beca used a mixture of artistic expression, including installation, painting, sculpture and performance, engaging with language, environmental and land rights issues.[45]

Decorative arts

_LACMA_55.101.4b.jpg.webp)

South Wales had several notable potteries in the late 18th and 19th centuries, beginning with the Cambrian Pottery (1764–1870, also known as "Swansea pottery") and including Nantgarw Pottery near Cardiff, which was in operation from 1813 to 1822 making fine porcelain, usually painted to a very high standard with flowers, and then utilitarian pottery until 1920. Portmeirion Pottery (from 1961) has never in fact been made in Wales.

Despite the fact that considerable quantities of silver (in association with lead), and much smaller amounts of gold, were mined in Wales, there was little silversmithing in Wales in the Early Modern period. It did not help that the Crown gave itself ownership of mines of precious metals, which were largely used for minting currency, some of which was marked with the Prince of Wales's feathers to show its origin. The Welsh gentry mostly had their silver made in English cities.

Arts and Crafts Movement

The Arts and Crafts movement (c. 1880–1920), with its devotion to the local, gave spark to the development of conceptually independent and identifiable Welsh art. Two elements of the movement were particularly amenable to the Welsh arts situation. First, the movement aspired to elevate the applied arts (pottery, furniture, etcetera) to the status of fine art.[46] Second, the development of Romantic nationalism, which drew from the Arts and Crafts Movement via its "advocacy of indigenous design, traditional ways of making objects, and the use of local materials."[47]

In Wales, at least until World War I, a genuine craft tradition still existed. Local materials, stone or clay, continued to be used as a matter of course.[48] Horace W. Elliot, an English gallery owner, visited the Ewenny Pottery (which dated back to the 17th century) in 1885, to both find local pieces and encourage a style compatible with the movement.[49] The pieces he brought back to London for the next twenty years revivified interest in Welsh pottery. The heavy salt glazes used for generations by local craftsmen had gone out of fashion, but the Arts and Crafts Movement brought new appreciation to their work.

A key promoter of the Arts and Crafts movement in Wales was Owen Morgan Edwards. Edwards was a reforming politician dedicated to renewing Welsh pride by exposing its people to their own language and history. For Edwards, "There is nothing that Wales requires more than an education in the arts and crafts."[50]—though Edwards was more inclined to resurrecting Welsh Nationalism than admiring glazes or rustic integrity.[51]

In architecture, Clough Williams-Ellis sought to renew interest in ancient building, reviving "rammed earth" or pisé construction in Britain. In 1925, In 1925 he began "his most famous creation, the village of Portmeirion, Merioneth, Wales, a Picturesque composition of individual buildings incorporating Classical details, salvaged fragments, and vernacular elements."[52] His daughter, Susan Williams-Ellis, would found the Portmeirion Pottery in the next generation (although none of this was ever made in Wales).

Contemporary Welsh Art

Today Welsh and Wales based artists, including members of The Welsh Group, the 56 Group Wales, the Royal Cambrian Academy and artists not affiliated with any particular group, provide a varied contemporary tapestry of art across Wales. From the Abstract Art of Brendan Stuart Burns[53] or Martyn Jones, to the expressive, modern figurative art of Shani Rhys James or Clive Hicks-Jenkins, from the politically charged work of Iwan Bala or Ivor Davies to the Pop Art of Ken Elias. The contemporary art of Wales is noted perhaps more for its variety, rather than having a single set agenda. However, perhaps due to market forces or the inspirational shapes and changing light, the Welsh landscape is still particularly well represented in commercial galleries throughout Wales and beyond, either through the expressive, almost abstract, techniques used by artists like David Tress or the more traditional approaches used by others like Rob Piercy.

Conceptual art in Wales

Conceptual art is represented in Wales with a number of successful artists including Bedwyr Williams and David Garner together with performance artists like the group TRACE,[54][55] creating and showing work in Wales and beyond. A number of Welsh galleries focus on conceptual art, with the most significant perhaps being Mostyn[56] in north Wales and Chapter Arts Centre and g|39[57] in south Wales. The Gold Medal at 'Y Lle Celf' in the National Eisteddfod of Wales has seen a notable trend towards more conceptual approaches over the last ten or so years, with Installation work being the usual focal point.[58] The 2003 development of the Artes Mundi prize and Wales's presence at the Venice Biennale has strengthened the country's international reputation for Conceptual and Installation art.

Artes Mundi and Wales at the Venice Biennale

Since 2003 the Artes Mundi biennial art prize has been held at the National Museum Cardiff. The prize is the biggest art prize in the United Kingdom with £40,000 for each year's winner.[59] Though the prize has included artists who use traditional media, like paint, this is usually only part of their practice, with the focus being very much on conceptual approaches. Though the exhibition takes place in Cardiff, the focus is on international artists,[60][61][62] with Tim Davies from Pembrokeshire [63] and Cornwall born Sue Williams[64] being the only Wales based artists to have featured to date.

Also adding to the international flavour in 2003, Wales took part in the Venice Biennale with its own pavilion[65][66] and has continued to do so ever since, showing work by conceptual Welsh artists including John Cale in 2009,[67] Tim Davies in 2011[68] and Bedwyr Williams in 2013.[69]

Welsh artists

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Wales |

|---|

|

| People |

| Art |

A selected list; for many more, see Category:Welsh artists or List of Welsh artists

- Barry Flanagan, (1941–2009), sculptor

- John Gibson, (1790–1866), sculptor

- Nina Hamnett (1890–1956), painter

- Augustus John (1878–1961), painter

- Gwen John (1876–1939), painter

- Sir William Goscombe John (1860–1952), sculptor

- David Jones (1895–1974), artist and poet

- Thomas Jones (1742–1803), painter

- Ceri Richards (1903–1971), painter

- Andrew Vicari (born 1938), painter

- Kyffin Williams (1918–2006), painter

- Richard Wilson (1714–1782), painter

See also

- Architecture of Wales

- Arts Council of Wales

- National Museum of Wales

- Welsh Artist of the Year

- Art in Cardiff

- Art of the United Kingdom

- Celtic art

- Irish art

- Scottish art

- Welsh Eisteddfod Gold Medal winners

References

- Houseley explores the lack of a clear sense of "Welsh art" among contemporary artists and in Wales generally. See also Morgan, 371–372.

- Kendrick's Cave BM touring exhibition, BM Highlights

- "Carving found in Gower cave could be oldest rock art", BBC News online, South-West Wales, July 25, 2011

- "Celtic Art in Iron Age Wales". National Museum of Wales. 3 May 2007. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- "Stunning ironwork firedog uncovered in farmers field". National Museum of Wales. 4 May 2007. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- "Exquisite Roman treasure gives up its secrets". National Museum of Wales. 9 September 2007. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- "Art historian Peter Lord talks The Tradition: A New History of Welsh Art: "It's a book for everyone" ", South Wales Evening Post, 7 March 2016. Accessed 3 April 2016

- "Strata Florida Abbey". Cadw. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "Medieval fragments". Stained Glass in Wales. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "Welsh church uncovers stunning medieval wall paintings", BBC News, 6 December 2013. Accessed 3 April 2016

- Llantwit Major Historical Society. "St. Illtud's Church". Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Tom Organ, "Reconstructing Medieval Wall Paintings at St Teilo's", www.building.conservation.com. Accessed 3 April 2016

- Claire Miller (28 March 2013). "'Mind-blowing' medieval art is unveiled in church". WalesOnline. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Cadw: Plas Mawr. Accessed 3 April 2016

- ""Faces of Wales" from the National Museum of Wales". Archived from the original on 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- National Museum of Wales: Katheryn of Berain. Accessed 2 April 2016

- British Listed Buildings: Plas Clough, Denbigh. Accessed 3 April 2016

- National Museum of Wales – William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke. Accessed 3 April 2016

- National Library of Wales: Paintings and Drawings. Accessed 18 April 2016

- Art Collections Online: Hugh Hughes. National Museum of Wales. Accessed 18 April 2016

- NMOW, Welsh Artists of the 18th Century. Though mainly known as a portraitist, John Downman, born and died in Wales, is also noted for unusually realistic Italian townscape studies, and some Welsh landscapes.

- Rosenthal, 52–64

- Rosenthal, 56

- Rosenthal, 61

- Rosenthal, 52 & 54. Image of Phaeton in a Thunderstorm Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Holcomb, 8

- Wigstead, Henry (1800). Remarks on a Tour to North and South Wales: In the Year 1797. W. Wigstead.

- Hayes, John. "Rowlandson, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24221. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Wilton & Lyles, 326-7

- Wilton & Lyles, pp. 176 & 260. Respectively: Private Collection, Mellon Centre for British Art, Tate.

- Harvey, John, The art of piety: the visual culture of Welsh Nonconformity, p.75, University of Wales Press, 1995, ISBN 0-7083-1298-5, ISBN 978-0-7083-1298-8

- 1855, Table p. xxii

- 1855, Appendix A, pp. 21–26

- 1855, pp. xxii–xxx

- "Royal Cambrian Academy".

- "National Museum of Wales, Walden". Archived from the original on 2014-01-06. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- The Welsh Group website. Retrieved 2015-01-20.

- Karen Price, "Art group marking 60 creative years", WalesOnline, 21 November 2008. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- David Moore, Mapping the Welsh Group at Sixty: The Exhibition, Planet Online. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- "Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru - National Library of Wales : Mapping the Welsh Group at 60". Archived from the original on 2012-12-18. Retrieved 2013-04-28.

- Peter Wakelin, “50 years of the Welsh Group", National Museum of Wales (1999), ISBN 0-7200-0472-1

- Peter Wakelin, "50 years of the Welsh Group", National Museum of Wales (1999), pp. 39–43, ISBN 0-7200-0472-1

- "Walesart, Ernest Zobole". BBC Wales online. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "Art in Wales: Politics of Engagement or Engagement with Politics?". artcornwall.org. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- Davies (2008) p. 56

- MacCarthy, Fiona (1994). William Morris. Faber and Faber. p. 593. ISBN 0-571-17495-7.

- "The Arts and Crafts Movement in Europe and America, 1880–1920: Design for the Modern World". Milwaukee Art Museum. 2005.

- Hilling, John B. (2018-08-15). The Architecture of Wales: From the First to the Twenty-First Century. University of Wales Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-78683-285-6. 'Arts and Crafts' to Early Modernism, 1900 to 1939

- Aslet, Clive (2010-10-04). Villages of Britain: The Five Hundred Villages that Made the Countryside. A&C Black. p. 477. ISBN 978-0-7475-8872-6.

- Davies, Hazel; Council, Welsh Arts (1988-01-01). O. M. Edwards. University of Wales Press on behalf of Welsh Arts Council. p. 28. ISBN 9780708309971. Sec. 3

- Rothkirch, Alyce von; Williams, Daniel (2004). Beyond the Difference: Welsh Literature in Comparative Contexts : Essays for M. Wynn Thomas at Sixty. University of Wales Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7083-1886-7.

- "Sir Clough Williams-Ellis". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- "Brendan Stuart Burns". Arts Council in Wales. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "TRACE: Displaced – Gwaith/Work". August 1, 2008.

- "what's welsh for performance? : trace dis:placed". www.performance-wales.org.

- "MOSTYN". MOSTYN.

- "g | 39". g39.org.

- "Art at the National Eisteddfod of Wales". August 1, 2008.

- "Artes Mundi 5 at the National Museum of Art, Cardiff". BBC. October 10, 2012.

- "Home". Artes Mundi.

- Simpson, Penny (November 1, 2012). "Artes Mundi 5". Wales Arts Review.

- "Artes Mundi - News, views, gossip, pictures, video - Wales Online".

- "Artes Mundi - Artes Mundi 1". Archived from the original on 2016-03-18. Retrieved 2015-07-27.

- "BBC Wales - Arts - Sue Williams". www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Arts Council of Wales | Cymru yn Fenis / Wales in Venice". Archived from the original on 2016-01-06. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "British Council − British Pavilion in Venice". Archived from the original on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "British Council − British Pavilion in Venice". Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "Wales Arts International | Wales at the Venice Biennale of Art". Archived from the original on 2018-09-29. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- "Venice Biennale: Bedwyr Williams looks to the stars". BBC News. June 1, 2013.

Sources

- Adele M Holcomb, John Sell Cotman, 1978, British Museum Publications ISBN 0714180041/5x

- Housley, William. Artists, Wales, Narrative and Devolution, in Devolution and identity, eds John Wilson, Karyn Stapleton, 2006, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-4479-0, ISBN 978-0-7546-4479-8, google books

- Morgan, Kenneth O., Rebirth of a Nation: Wales 1880–1980, Volume 6 of History of Wales, Oxford University Press, 1982, ISBN 0-19-821760-9, ISBN 978-0-19-821760-2, google books

- Rosenthal, Michael, British Landscape Painting, 1982, Phaidon Press, London

- Wakelin, Peter, Creu cymuned o arlunwyr: 50 mlynedd o'r Grŵp Cymreig/Creating an Art Community, 50 Years of the Welsh Group, National Museum of Wales, 1999, ISBN 0-7200-0472-1, ISBN 978-0-7200-0472-4, google books

- "1855" – Report of the Department of Science and Art of the Committee of Council on Education: with appendix : presented to both Houses of Parliament by command of Her Majesty, Department of Science and Art, H.M.S.O., 1855, online text

- Andrew Wilton & Anne Lyles, The Great Age of British Watercolours (1750–1880), 1993, Prestel, ISBN 3-7913-1254-5

Further reading

- Lord, Peter, Imaging the nation, Volume 2 of Visual culture of Wales, University of Wales Press, 2000, ISBN 0-7083-1587-9, ISBN 978-0-7083-1587-3

- Lord, Peter, The Betws y Coed Artists' Colony: Clarence Whaite and the Welsh Art World, 2009, Coast and Country Productions Ltd, ISBN 1-907163-06-9

- Rowan, Eric, Art in Wales: an illustrated history, 1850–1980, Welsh Arts Council, University of Wales Press, 1985,

Alan Torjussen, "A Wales Art Collection – Casgliad Celf Cymru", bilingual art education project for schools and adults (A3 cards, A6 cards, CD Rom), Genesis 2014, ISBN 978-0-9535202-7-5 etc.

Alan Torjussen, "Teaching Art in Wales – Dysgu Celf yng Nghymru", bilingual art education project for schools and adults (A3 cards, teachers book, videos), Genesis & University of Wales Press 1997