Armour in the 18th century

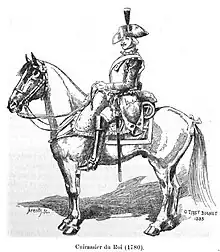

Armour in the 18th century was minimalist and restricted almost entirely to cavalry, primarily to cuirassiers and, to a lesser degree, carabiniers and dragoons. Armour had been in rapid decline since the Thirty Years' War, although some archaisms had lingered on into the early years of the 18th century, like Austrian cuirassiers with buff coats and lobster-tailed helmets or Hungarian warriors with mail armour and shields. With the exception of Poland-Lithuania, which still made use of hussars wearing suits of plate armour, armour in Europe was primarily restricted to a (sometimes blackened) breast- and backplate, the cuirass, and a simple iron skull cap worn under the hat. By the later 18th century, there were two contradicting developments. Many cuirassier regiments were discarding their cuirasses, while helmets in the form of so-called dragoon helmets, made of brass or leather, made a comeback among the cavalry and infantry.

_-_Private%252C_15th_Regiment_of_Cuirassiers_'Diemar'_-_RCIN_404295_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

Body armour after 1700

The usage of body armour in Europe had seen a steady decline since the late 16th century, adjusting to the changes in warfare caused by the increased role of infantry and firearms. The first element of body armour to fall out of use was foot and leg protection. Around the same time plate and mail horse barding was relegated to a ceremonial role until disappearing for good in the mid-17th century.[1]

In the 18th century, the only troop type to wear body armour was the cuirassier, named after their cuirass.[2] Described as "big men on big horses" whose main task was to defeat the enemy cavalry, they were the closest thing to the heavily armoured knights of old.[3] Usually painted black, their cuirass was rather uncomfortable to wear and quite heavy, as it was expected to withstand a musket shot before being accepted to service.[2] Head protection was neglected throughout much of the 18th century. After the lobster-tailed helmets had been abandoned by most European armies by the second half of the 17th century, there were no proper helmets that replaced them. Instead of helmets, both infantry and cavalry resorted to hats made of linen or cloth and fur caps. If at all, simple iron skull caps were worn under these hats.[4] Alternatively, the hats might be reinforced by an iron framework. An 18th-century commander known to have worn a skull cap was August the Strong, whose specimen weighted almost 10 kilogram.[5] In any case, they offered no protection against bullets and were only meant to protect the wearer from sword cuts. Hence, they were primarily restricted to cavalry.[4] Dragoons, mounted infantry, also often wore iron skull caps, although their battlefield purpose had become indistinguishable from that of other cavalry by around 1750.[6]

In Sweden, Charles XII (r. 1697–1718) abandoned all defensive armour for his cavalry as he favoured aggressive charges at high speed.[7] Duke Marlborough, who commanded the British troops during the War of the Spanish Succession, also ordered the abandonment of breast and back plates in 1702, although he would reissue breast plates a few years later, to be worn under the coats.[8] Russia lacked heavy cavalry in any form until von Münnich's reforms in the early 1730s, reyling entirely on dragoons and auxiliaries instead.[9]

A type of leg protection were massive leather boots for cuirassiers, protecting the wearer already during the charge, which happened knee-to-knee. However, they were so cumbersome that the soldier had trouble to mount his horse and, even more problematic, making it nearly impossible for him to walk after dismounting. Hence, a cuirassier fighting on foot "was as much use as a dead man."[2]

One piece of armour which continued to be worn was the gorget, although its size was rapidly decreasing. It was not intended to offer protection, but rather to display the high rank of its wearer.

In Poland, some gorgets had applications bearing scenes of Christian iconography, like Virgin Mary or saints. They "functioned symbolically as a 'spiritual buckler'."[10]

The cuirass of Prince Eugene of Savoy

The cuirass of Prince Eugene of Savoy Prussian cuirassier tricorne hat and skull cap from the time of Frederick the Great

Prussian cuirassier tricorne hat and skull cap from the time of Frederick the Great Iron framework for tricorne

Iron framework for tricorne Peter the Great wearing a large gorget

Peter the Great wearing a large gorget Painting of Louis XV dating from 1748. Although such suits of armour had long fallen out of use it remained fashionable for the nobility to be painted while wearing them.

Painting of Louis XV dating from 1748. Although such suits of armour had long fallen out of use it remained fashionable for the nobility to be painted while wearing them.

Early archaisms and exceptions to the rule

Commanders still would occasionally wear body armour during the early decades of the 18th century.

Hungarian general János Bottyán, for example, wore a breastplate during a siege in 1705, which saved his life after being hit by a bullet.[11]

Another archaism during the early years of the 18th century were Hungarian horsemen known as Panzerstecher ("armour piercer"), equipped with an armour piercing sword, mail armour, an iron skull cap with mail aventail and a small shield.[12] Initially, the Hungarian aristocracy did not normally wear mail armour on its own but under a cuirass,[13] but this had changed by the second half of the 17th century,[11] while their old lobster-tailed helmet had made place to the new, simple skull cap with aventail around 1630.[14] Contributing many thousand fighters, the Panzerstecher successfully fought in the Great Turkish War,[15] but after the defeat of the Hungarian uprising of Francis II Rákóczi in 1711, mail armour was restricted to a few hussar captains.[11] It finally disappeared for good after the war of the Austrian succession.[16]

A unique Polish development is a form of scale armour, the karacena, that developed in the last quarter of the 17th century and remained is use until the middle of the 18th century. Being a product of Polish Sarmatism, it was inspired by ancient Sarmatian, Scythian, Dacian and late ancient Roman armour. Karacena helmets were either based on the lobster-tailed helmet or the Muslim turban. It was a display of ideology rather than a practical armour, being extremely heavy and expensive. Therefore, it was limited to the upper stratum of the Polish aristocracy and high-ranking cavalry officers.[17]

In eastern Europe, Russia maintained close ties with the Kalmyk Khanate at the shores of the Caspian Sea and enlisted its horsemen for various campaigns like the Russo-Persian war of 1722-1723,[18] although they proved to be more useful against other steppe armies.[19] Most of them fought as light cavalry, but the nobility wore various kinds of armour, like heavy wool kaftans with metal plates sewn on or Persian-style armour. Greatly appreciated by the Kalmyks, armour remained an important status symbols even though its practical use was declining. In the later 18th century, a fine piece of armour would still be worth over 50 horses.[20]

An Austrian general from the beginning of the 18th century wearing a cuirass and additional steel plates for shoulder protection.

An Austrian general from the beginning of the 18th century wearing a cuirass and additional steel plates for shoulder protection..jpg.webp)

_(cropped).tiff.jpg.webp) Austrian cavalry officer in 1716

Austrian cavalry officer in 1716

.png.webp) August the Strong leading his heavily armoured Polish hussars to victory at the battle of Kalisz in 1706

August the Strong leading his heavily armoured Polish hussars to victory at the battle of Kalisz in 1706 The scale armour (karacena) of Jan Sobieski. This type of armour was a uniquely Polish development, although its usage was restricted to the elite.

The scale armour (karacena) of Jan Sobieski. This type of armour was a uniquely Polish development, although its usage was restricted to the elite. Papal cuirassiers with body armour and helmets, 1721

Papal cuirassiers with body armour and helmets, 1721.jpg.webp) Saxon cuirassier wearing parade armour, 1730

Saxon cuirassier wearing parade armour, 1730

Developments during the second half of the 18th century

By the French Revolutionary Wars at the end of the 18th century, the use of body armour had declined to virtual extinction. Of all principal European armies, it was only the Austrian one that continued to employ armoured cuirassiers en masse.[21] However, except when confronting the Ottomans like during the war of 1788-1791, only a breastplate was worn.[22] The Austrian reform of 1798 even increased the number of cuirassier regiments by three,[23] although the state of the cuirass itself was not altered, not abandoning it, but also not readding the backplate of old. This would eventually proof fatal during the battle of Eckmühl in 1809, when the French cuirassiers with their full cuirasses decisively defeated the Austrian cuirassiers.[24] Indeed, Napoleonic France would eventually put much emphasis on armoured cavalry, although the former Cuirassiers du Roi regiment, known after the revolution as Cavalerie-Cuirassiers, would continue to be the sole French regiment using body armour until the reforms of 1802/1803.[25]

By the order of king Frederick William II, Prussian cuirassiers were discarding their armour. This was the case first for a few regiments participating in the Prussian invasion of Holland in 1787 and then completely in 1790. They were not reintroduced until 1814/1815.[26] Meanwhile, most German minor states had no cuirassiers regiments at all, and those of the Electorate of Hanover did not make use of armour.[27] The Russians discarded their breast plates after 1774, during the reforms of Grigory Potemkin, who preferred cavalry to be as light as possible.[28]

The last decades of the 18th century saw the introduction of helmets made of leather. The French introduced a dragoon regiment wearing Pseudo-Phryrian brass helmets with horse hair crests in 1743. Two decades later this helmet type was adopted by all dragoons.

The British followed the French example and raised light dragoon regiments wearing brass helmets with green (later scarlet) turbans and crests with red horse hair in 1759. The helmet came soon to be associated with Emsdorf due to the outstanding service of the 15th Light Dragoons regiment at the Battle of Emsdorf in 1760, just a year after their raising. From around 1780 it fell out of use in favour of the so-called "Tarleton helmets". Made out of leather, it had "a peak over the eyes, a turban round the heapiece, and a black fur crest over the top from front to rear." The 15th dragoon regiment, however, kept the old "Emsdorf helmets" until at least 1789.[29] While brass and boiled leather helmets were incapable of deflecting bullets they were sufficient enough to stop sword blows, which were the preferred cavalry weapons.[30]

Over the course of the Napoleonic wars in the early 19th century, this generation of helmets fell out of use in most European armies in favour of shako hats. Exceptions were the heavy French cavalry or the Bavarians with their unique raupenhelm, which they retained until the second half of the 19th century.

.jpg.webp) A dragoon of the Volontaires de Saxe (1743–1750) regiment wearing a pseudo-Phrygian helmet made of brass.

A dragoon of the Volontaires de Saxe (1743–1750) regiment wearing a pseudo-Phrygian helmet made of brass..jpg.webp) British lieutenant of the 15th dragoons with silver helmet, 1768

British lieutenant of the 15th dragoons with silver helmet, 1768.jpg.webp) British dragoon wearing a brass or leather helmet with Totenkopf, 1775

British dragoon wearing a brass or leather helmet with Totenkopf, 1775.jpg.webp) British commander Banastre Tarleton wearing the eponymous leather helmet with large plume, 1782

British commander Banastre Tarleton wearing the eponymous leather helmet with large plume, 1782 French dragoon in 1786 wearing a helmet that already resembles those of the Napoleonic wars

French dragoon in 1786 wearing a helmet that already resembles those of the Napoleonic wars_(cropped).tiff.jpg.webp) Belgian revolutionary cavalry wearing a leather helmet with colourful plume, 1789

Belgian revolutionary cavalry wearing a leather helmet with colourful plume, 1789.jpg.webp) Bavarian infantry after the reform of 1790, wearing leather helmets designed by Lord Rumford, therefore also known as "Rumford-Kasket".

Bavarian infantry after the reform of 1790, wearing leather helmets designed by Lord Rumford, therefore also known as "Rumford-Kasket"..jpg.webp) Russian Potemkin-uniforms worn between 1786 and 1796

Russian Potemkin-uniforms worn between 1786 and 1796 Austrian cuirassier with breastplate and leather helmet after the reform of 1798

Austrian cuirassier with breastplate and leather helmet after the reform of 1798 Bavarian flag bearer after the reform of 1800, wearing the iconic "Raupenhelm"

Bavarian flag bearer after the reform of 1800, wearing the iconic "Raupenhelm"

Usage of armour in tournaments

From 1776, Sweden saw several pseudo-medieval festivals that also included jousting tournaments. To protect themselves, the participants wore plate armour inspired by late medieval models.

Outside of Europe

While its use was in continuous decline body armour continued to be worn throughout most non-European cultures.

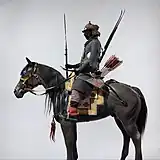

In Tibet it was around the 18th century when mail completely replaced lamellar armour as the preferred protection for cavalrymen, which may be attributed to Chinese influence.[31] Known as a lung gi khrab, most of it was imported from India and the Middle East. Horse armour also continued to be utilized, albeit rarely, until the early 20th century.[32] The lamellar armour, byang bu'i khrab, continued to be worn by infantry. Helmets were either of a simple spherical type made out of one piece or segmented.[33]

Qing officer wearing blue lamellar armour, late 18th century

Qing officer wearing blue lamellar armour, late 18th century.jpg.webp) Qing officer wearing mail shirt, late 18th century

Qing officer wearing mail shirt, late 18th century Set of Tibetan cavalry armour, 18th–19th centuries

Set of Tibetan cavalry armour, 18th–19th centuries

Notes

- Breiding 2005, pp. 16–17.

- Duffy 1987, p. 88.

- Duffy 1987, p. 85.

- Jordan 1989, p. 102.

- Demmin 1870, pp. 242–243.

- Childs 1982, p. 108.

- Childs 1982, p. 130.

- Falkner 2014, pp. 101–102.

- Konstam 1996, pp. 7–8.

- Ostrowski 1999, p. 213.

- Kovács 2010, p. 254.

- von Leber 1846, pp. 280–281, note 183.

- Kovács 2010, p. 248.

- Kovács 2010, pp. 246–247.

- Kovács 2010, p. 253, note 825.

- von Leber 1846, p. 502.

- Ostrowski 1999, p. 209.

- Khodarkovsky 1992, p. 167.

- Khodarkovsky 1992, p. 55.

- Khodarkovsky 1992, pp. 49–50.

- Haythornthwaite 2013, p. 16.

- Haythornthwaite 1986, p. 9.

- Haythornthwaite 1986, p. 5.

- Haythornthwaite 1986, p. 12.

- Haythornthwaite 2013, p. 18.

- Hofschröer 1985, p. 15.

- Wilson 2015, p. 197.

- Menning 2004, pp. 279–280.

- Matthews 1964, pp. 175–177.

- Peterson 2000, p. 315.

- LaRocca 2006, p. 9.

- LaRocca 2006, p. 5.

- LaRocca 2006, pp. 4–5.

Literature

- Breiding, Dirk H. (2005). "Horse Armor in Medieval and Renaissance Europe: An Overview". The Armored Horse in Europe, 1480-1620. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 8–18.

- Childs, John (1982). Armies and Warfare in Europe. 1648-1789. Manchester University.

- Demmin, Auguste (1870). Weapons of War. Being a History of Arms and Armour from the Earliest Period to the Present Time. Bell & Daldy.

- Duffy, Christopher (1987). The Military Experience in the Age of Reason. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Falkner, James (2014). Marlborough's War Machine 1702-1711. Pen & Sword Military.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (1986). Austrian Army of the Napoleonic Wars (2). Cavalry. Osprey.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip (2013). Napoleonic Heavy Cavalry & Dragoon Tactics. Osprey.

- Hofschröer, Peter (1985). Prussian Cavalry of the Napoleonic Wars (1). 1792-1807. Osprey.

- Jordan, Klaus (1989). "Die Helmentwicklung vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart". Burgen und Schlösser. Zeitschrift für Burgenforschung und Denkmalpflege (in German). Deutsche Burgenvereinigung e.V. 30 (2): 99–106.

- Khodarkovsky, Michael (1992). Where Two Worlds Met: The Russian State and the Kalmyk Nomads, 1600-1771. Cornell University.

- Konstam, Angus (1996). Russian Army of the Seven Years War (2). Osprey.

- Kovács, Tibor (2010). Huszárfegyverek a 15–17 században (in Hungarian). Martin Opitz Kiadó.

- LaRocca, Donald J. (2006). Warriors of the Himalayas. Rediscovering the Arms and Armor of Tibet. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Matthews, A.S. (1964). "The Uniform of the 15th (or King's) Light Dragoons, 1789". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. Society for Army Historical Research. 42 (172): 175–178.

- Menning, Bruce W. (2004). "G. A. Potemkin and A. I. Chernyshev. Two Dimensions of Reform and Russia's Military Frontier". Reforming the Tsar's Army Military Innovation in Imperial Russia from Peter the Great to the Revolution. Cambridge University. pp. 273–291.

- Ostrowski, Jan K. (1999). Art in Poland, 1572-1764. Land of the Winged Horsemen. Yale University Press.

- Peterson, Harold Leslie (2000). Arms and Armor in Colonial America, 1526-1783. Dover.

- von Leber, Fr. (1846). Wien's kaiserliches Zeughaus (in German).

- Wilson, Peter H. (2015). "The Armies of the German Princes". In Frederick C. Schneid (ed.). European Armies of the French Revolution. 1789–1802. University of Oklahoma. pp. 182–210.

.jpg.webp)