Arcade (comics magazine)

Arcade: The Comics Revue is a magazine-sized comics anthology created and edited by cartoonists Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith to showcase underground comix. Published quarterly by the Print Mint, it ran for seven issues between 1975 and 1976. Arriving late in the underground era, Arcade "was conceived as a 'comics magazine for adults' that would showcase the 'best of the old and the best of the new comics'".[1] Many observers credit it with paving the way for the Spiegelman-edited anthology Raw, the flagship publication of the 1980s alternative comics movement.

| Arcade: The Comics Revue | |

|---|---|

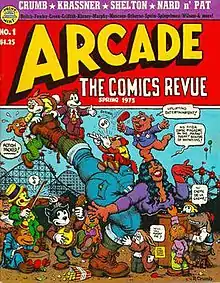

Arcade #1, artwork by R. Crumb. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Print Mint |

| Schedule | Quarterly |

| Format | Oversize |

| Genre | Underground |

| Publication date | Spring 1975 – Fall 1976 |

| No. of issues | 7 |

| Creative team | |

| Created by | Art Spiegelman & Bill Griffith |

| Written by | Steve Anker, Charles Bukowski, William S. Burroughs, Samuel Coleridge, David Cohen, George DiCaprio, Will Fowler, J. Hoberman, Paul Krassner, Jane Lynch, Michael Reynolds |

| Artist(s) | Robert Armstrong, Mark Beyer, Michele Brand, M. K. Brown, Harrison Cady, Oliver Christianson (aka Revilo), Robert Crumb, Kim Deitch, Justin Green, Bill Griffith, Geoffrey Hayes, Rory Hayes, Gerald Jablonski, Jay Kinney, B. Kliban, Aline Kominsky, George Kuchar, Bill Lynch, Jay Lynch, Curt McDowell, Michael McMillan, Victor Moscoso, Willy Murphy, Diane Noomin, James Osborne, Spain Rodriguez, Gilbert Shelton, Art Spiegelman, Lulu Stanley, Robert Williams, S. Clay Wilson |

| Editor(s) | Art Spiegelman & Bill Griffith |

Well-known creators who contributed to the anthology include R. Crumb, Kim Deitch, Jay Kinney, Aline Kominsky, Jay Lynch, Spain Rodriguez, Gilbert Shelton and S. Clay Wilson.[2]

Overview

By the mid-1970s, the underground comix movement was encountering a slowdown,[1] and Spiegelman and Griffith conceived of Arcade as a "safe berth". It stood out from similar publications by having an ambitious editorial plan, in which Spiegelman and Griffith attempted to show how comics connected to the broader realms of artistic and literary culture.[3] Arcade also introduced comic strips from ages past, as well as contemporary literary pieces by writers such as William S. Burroughs and Charles Bukowski,[4] and illustrated nonfiction pieces by writers like Paul Krassner and J. Hoberman.

Publication history

Spiegelman and Griffith, based in the San Francisco Bay Area — the epicenter of the underground movement[5] — originally conceived of a comics magazine for adults in c. 1971, planning to call it Banana Oil as an homage to Milt Gross (who originated the non-sequitur as a phrase deflating pomposity and posing).[6] The publisher, Company & Sons, they approached about it, but was unable to make it a reality.[6]

Some years later, in Spring 1975, with the help of Print Mint, they were able to launch the magazine as Arcade. Soon after, however, co-editor Spiegelman moved back to his original home of New York City,[7] which put most of the editorial work for Arcade on the shoulders of Griffith and his cartoonist wife, Diane Noomin. This, combined with distribution problems, retailer indifference, and a general failure to find a devoted audience,[1] led to the magazine's 1976 demise.

Contributors

Contributors to every issue of Arcade included Spiegelman, Griffith, Robert Armstrong, Robert Crumb, Justin Green, Aline Kominsky, Michael McMillan, Diane Noomin, and Spain Rodriguez. Crumb illustrated five of the seven front covers. Each issue contained a reprint of work by a cartoonist from the medium's Golden Age, including H. M. Bateman, Harrison Cady, Billy DeBeck, Milt Gross, and George McManus. Each issue's title page contained individual self-portraits by the contributors.

Issue guide

| # | Date | Cover artist | Back cover artist | Contributors | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spring 1975 | Robert Crumb | Victor Moscoso | Aldo Bobbo (Robert Armstrong), Robert Crumb, Kim Deitch, Will Fowler, Justin Green, Bill Griffith, Jay Kinney, Aline Kominsky, Paul Krassner, George Kuchar, Jay Lynch, Curt McDowell, Michael McMillan, Willy Murphy, Diane Noomin, James Osborne, Spain Rodriguez, Gilbert Shelton, Art Spiegelman, and S. Clay Wilson; plus a Harrison Cady reprint | |

| 2 | Summer 1975 | Robert Crumb | Art Spiegelman | Armstrong, David Cohen, Crumb, Deitch, Green, Griffith, Rory Hayes, Kinney, Kominsky, Krassner, Kuchar, Lynch, McMillan, Murphy, Noon, Osborne, Shelton, Spain, and Spiegelman; plus a W. E. Hill reprint | |

| 3 | Fall 1975 | Robert Crumb | Gilbert Shelton | Armstrong, Charles Bukowski/Crumb, Sally Cruikshank, Green, Griffith, Hayes, Denis Kitchen, Kominsky, Kuchar, Jane Lynch, McMillan, Murphy, Noomin, Jim Osborne, Joe Schenkman, Shelton, Spain, Spiegelman, Wilson; plus a Milt Gross reprint | |

| 4 | Winter 1975 | Robert Crumb | Justin Green | Armstrong, William S. Burroughs, Crumb, Deitch, Green, Griffith, Hayes, J. Hoberman, Kominsky, Bill Lynch, Curt McDowell, McMillan, Murphy, Noomin, Michael Reynolds, Schenkman, Shelton, Spain, Spiegelman, Robert Williams, Wilson; plus a George McManus reprint | |

| 5 | Spring 1976 | Jay Lynch | Robert Williams | Armstrong, Michele Brand, M. K. Brown, Dirk Burhans, Crumb, Deitch, George DiCaprio, Green, Griffith, Hayes, Hoberman, Kominsky, McDowell, McMillan, Murphy, Noomin, Spain, Spiegelman, Wilson, Williams; plus a Billy DeBeck reprint | |

| 6 | Summer 1976 | Robert Crumb | Michael McMillan | Armstrong, Mark Beyer, Brown, Crumb, Deitch, Green, Griffith, Geoffrey Hayes, Hayes, Hoberman, Gerald Jablonski, Kominsky, McMillan, Murphy, Noomin, Larry Rippee, Spain, Spiegelman, Wilson; plus a H. M. Bateman reprint | Includes a tribute to the recently deceased Willy Murphy by Ted Richards. |

| 7 | Fall 1976 | M. K. Brown | B. Kliban | Armstrong, Beyer, Brand, Oliver Christianson (aka Revilo), Crumb, Deitch, Green, Griffith, Rory Hayes, Hoberman, B. Kliban, Kominsky, McMillan, Noomin, Spain, Lulu Stanley, Williams; plus "Sex Comics of the Thirties" (Tijuana bible) section |

Legacy

Although short-lived, Arcade still has admirers. Famed comics writer Alan Moore said it was "the only truly worthwhile material produced during the 1970s".[1] With the general waning of the underground scene, however, Spiegelman despaired that comics for adults might fade away for good. Frustrated with editing his peers because of the tension and jealousies involved, for a time Spiegelman swore he would never edit another magazine.[8] Nonetheless, by 1980, Spiegelman and his wife/collaborator Françoise Mouly launched Raw, a "graphix magazine", hoping their unprecedented approach would bypass readers' prejudices against comics and force them to look at the work with new eyes.

References

- Fox, M. Steven. "Arcade, The Comics Revue", ComixJoint. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Sacks, Jason; Dallas, Keith (2014). American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1970s. TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-1605490564.

- Grishakova, Marina; Ryan, Marie-Laure (2010). Intermediality and Storytelling. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-023774-0,pp=67–68.

- Buhle, Paul (2004). From the Lower East Side to Hollywood: Jews in American Popular Culture. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-598-1, p. 252.

- Lopes, Paul. Demanding Respect: The Evolution of the American Comic Book (Temple University Press, 2009), p. 77.

- "Bill Griffith: Politics, Pinheads, and Post-Modernism", The Comics Journal #157 (Mar. 1993), p. 73.

- Witek, Joseph, ed. (2007). "Chronology". Art Spiegelman: Conversations. University Press of Mississippi. pp. xvii–xiii. ISBN 978-1-934110-12-6, p. xix.

- Kaplan, Arie (2006). "Art Spiegelman". Masters of the Comic Book Universe Revealed!. Chicago Review Press. pp. 99–124. ISBN 978-1-55652-633-6, p. 108.