Venus de Milo

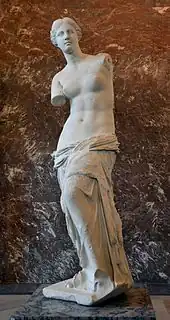

The Venus de Milo (/də ˈmaɪloʊ, də ˈmiːloʊ/ də MY-loh, də MEE-loh; Ancient Greek: Ἀφροδίτη τῆς Μήλου, romanized: Aphrodítē tēs Mḗlou) or Aphrodite of Melos is an ancient Greek sculpture that was created during the Hellenistic period. It is one of the most famous works of ancient Greek sculpture, having been prominently displayed at the Louvre Museum since shortly after the statue was rediscovered on the island of Milos, Greece, in 1820.

| Venus de Milo | |

|---|---|

| Ἀφροδίτη τῆς Μήλου | |

| |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Subject | Venus |

| Condition | Arms broken off; otherwise intact |

| Location | Louvre, Paris |

The Venus de Milo is believed to depict Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, whose Roman counterpart was Venus. Made of Parian marble, the statue is larger than life size, standing over 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) high. The statue is missing both arms, with part of one arm, as well as the original plinth, being lost after the statue's rediscovery.

Description

The Venus de Milo is an over 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) tall[lower-alpha 1] Parian marble statue[3] of a Greek goddess, most likely Aphrodite, depicted with a bare torso and drapery over the lower half of her body.[2] The figure's head is turned to the left.[5] The statue is missing both arms, the left foot, and the earlobes.[6] There is a filled hole below her right breast that originally contained a metal tenon that would have supported the right arm.[7] The Venus' flesh is polished smooth, but chisel marks are still visible on other surfaces.[8]

Stylistically, the sculpture combines elements of classical and Hellenistic art.[5] Features such as the small, regular eyes and mouth, and the strong brow and nose, are classical in style, while the shape of the torso and the deeply carved drapery are Hellenistic.[9]

Discovery and history

Discovery

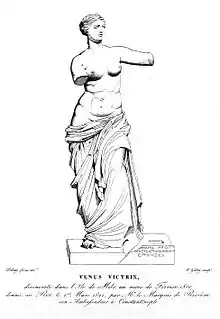

The Venus de Milo was discovered on 8 April 1820 by a Greek farmer on the island of Milos. Olivier Voutier, a French sailor interested in archaeology, witnessed the discovery and encouraged the farmer to continue digging.[10] Voutier and the farmer uncovered two large pieces of the sculpture and a third, smaller piece. A fragment of an arm, a hand holding an apple, and two herms were also found alongside the statue.[11] Two inscriptions were also apparently found with the Venus. One, transcribed by Dumont D'Urville, a French naval officer who arrived on Milos shortly after the discovery,[12] commemorates a dedication by one Bakchios son of Satios, the assistant gymnasiarch. The other, recorded on a drawing made by Auguste Debay, names Alexandros of Antioch.[13][14] Both inscriptions are now lost.[13] Other sculptural fragments found around the same time include a third herm, two further arms, and a foot with sandal.[13]

Dumont D'Urville wrote an account of the find.[10] According to his testimony, the Venus statue was found in a quadrangular niche.[4] If this findspot were the original context for the Venus, the niche and the gymnasiarch's inscription suggests that the Venus de Milo was installed in the gymnasium of Melos.[15] An alternative theory proposed by Salomon Reinach is that the findspot was instead the remains of a lime kiln, and that the other fragments had no connection to the Venus;[16] this theory is dismissed by Christofilis Maggidis as having "no factual basis".[17]

After stopping in Melos, D'Urville's ship sailed to Constantinople, where he reported the find to the Comte de Marcellus, assistant to Charles François de Riffardeau, marquis de Rivière, the French ambassador. Rivière agreed that Marcellus should go to Melos to buy the statue.[18] By the time Marcellus arrived at Melos, the farmer who discovered the statue had already received another offer to buy it, and it had been loaded onto a ship; the French intervened and Marcellus was able to buy the Venus.[19] It was brought to France, bought by Louis XVIII, and installed in the Louvre.[19]

Identification

The Venus de Milo is probably a sculpture of the goddess Aphrodite, but its fragmentary state makes secure identification difficult.[20] The earliest written accounts of the sculpture, by a French captain and the French vice-consul on Melos, both identify it as representing Aphrodite holding the apple of discord, apparently on the basis of the hand holding an apple found with the sculpture.[21] An alternative identification proposed by Reinach is that she represents the sea-goddess Amphitrite, and was originally grouped with a sculpture of Poseidon from Melos, discovered in 1878.[22] Other proposed identifications include a Muse, Nemesis, or Sappho.[23]

The authorship and date of the Venus de Milo were both disputed from its discovery. Within a month of its acquisition by the Louvre, three French scholars had published papers on the statue, disagreeing on all aspects of its interpretation: Toussaint-Bernard Éméric-David thought it dated to c. 420 BC – c. 380 BC, between Phidias and Praxiteles; Quatremère de Quincy attributed it to the mid-fourth century and the circle of Praxiteles; and the Comte de Clarac thought it a later copy of a work by Praxiteles.[24] The scholarly consensus in the 19th century was that the Venus dated to the fourth century BC. At the end of the 19th century, Adolf Furtwängler was the first to argue that it was in fact late Hellenistic, dating to c. 150 BC – c. 50 BC,[25] and this dating continues to be widely accepted.[26]

One of the inscriptions discovered with the statue, which was drawn by Debay as fitting into the missing section of the statue's base, names the sculptor as Alexandros of Antioch on the Maeander. The inscription must therefore date to after 280 BC, when Antioch was founded; the lettering of the inscription suggests a date of 150–50 BC.[27] Maggidis argues based on this inscription, as well as the style of the statue and the increasing prosperity of Melos in the period due to Roman involvement on the island which he suggests is a plausible context for the commissioning of the sculpture, that it probably dates to c. 150 BC – c. 110 BC.[28] Rachel Kousser, though doubting the association of the Alexandros plaque with the Venus,[29] agrees with Furtwängler's dates for the sculpture.[30] Marianne Hamiaux suggests c. 160 BC – c. 140 BC.[31] Jean-Luc Martinez argues that the Alexandros inscription was not part of the Venus.[32]

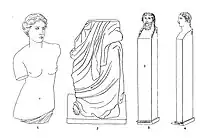

Reconstructions

Without arms, it is unclear what the statue originally looked like. The original appearance of the Venus has been disputed since 1821, with de Clarac arguing that the Venus was a single figure holding an apple, whereas Quatremere held that she was part of a group, with her arms around another figure.[33] Other proposed restorations have included the Venus holding wreaths, a dove, or spears.[34]

Wilhelm Fröhner suggested in 1876 that the Venus de Milo's right hand held the drapery slipping down from her hips, while the left held an apple; this theory was expanded on by Furtwängler.[35] Kousser considers this the "most plausible" reconstruction.[36]

Hamiaux suggests that the Venus de Milo is of the same sculptural type as the Capuan Venus and another sculpture of Aphrodite from Perge. She argues that all derive from the cult statue in the temple of Aphrodite on the Acrocorinth, which depicted Aphrodite admiring herself in a shield.[37]

Fame

Upon its discovery in 1820, the Venus de Milo was considered to be a significant artistic finding, but did not gain its status as an icon until later on. The Louvre and in turn, French art as a whole, had suffered great losses when Napoleon Bonaparte's looted art collection was returned to their countries of origin. The museum lost some of its most iconic pieces, such as the Vatican Museums' Laocoön and His Sons and the Uffizi Gallery's Venus de' Medici. The hole that the restitutions left in French culture allowed the perfect path for the Venus de Milo to become an international icon. Based on early drawings, the plinth that had been detached from the statue was known to have dates on it, which revealed that it was created after the Classical period, which was the most desirable artistic period. This caused the French to hide the plinth, in an effort to conceal this fact before the statue's introduction to the Louvre in 1821. The Venus de Milo held a prime spot in the gallery, and became iconic, mostly due to the Louvre's branding campaign and emphasis on the statue's importance in order to regain national pride.

The great fame of the Venus de Milo during the 19th century owed much to a major propaganda effort by the French authorities. In 1815, France had returned the Venus de' Medici (also known as the Medici Venus) to the Italians. The Medici Venus, regarded as one of the finest classical sculptures in existence, caused the French to promote the Venus de Milo as a greater treasure than that which they recently had lost. The statue was praised dutifully by many artists and critics as the epitome of graceful female beauty. However, Pierre-Auguste Renoir was among its detractors, calling it "as beautiful as a gendarme".[38]

Second World War

During the beginning of the German invasions during World War II, Jacques Jaujard, the director of the French Musées Nationaux, anticipating the fall of France, decided to organize the evacuation of the Louvre art collection to the provinces.[39] Venus de Milo, along with The Winged Victory of Samothrace, was kept at Château de Valençay. In August 1944, the Château was the site of combat between maquis, Vichy and German forces, and at one point German soldiers forced their way into the Château.[40]

Reception

The Venus de Milo is perhaps the most famous ancient Greek statue in the world, seen by more than seven million visitors every year.[41]

The statue has greatly influenced masters of modern art. French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne drew the Venus in 1881. René Magritte painted a reduced-scale version of plaster, with bright pink and dark blue, entitled Les Menottes de Cuivre or The Copper Handcuffs in 1931. Several of Salvador Dalí's works reference the sculpture, including the 1936 statue Venus de Milo with Drawers, a half-size plaster cast, painted and covered the slightly open drawers with metal knobs and fur pom-poms. This recreation of the famous sculpture was meant to display the "goddess of love as a fetishistic anthropomorphic cabinet with secret drawers filled with a maelstrom of mysteries of sexual desires that only a modern psychoanalyst can interpret" (Oppen & Meijer, 2019).[42] Dalí also painted The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1969–70) with its repeated images of the statue. More recently the Neo-Dada Pop artist Jim Dine has often utilized the Venus de Milo in his sculptures and paintings since the 1970s.

The statue was formerly part of the seal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), one of the oldest associations of plastic surgeons in the world.[43]

In February 2010, the German magazine Focus featured a doctored image of this Venus giving Europe the middle finger, which resulted in a defamation lawsuit against the journalists and the publication.[44] They were found not guilty by the Greek court.[45]

The image of the Venus de Milo is often seen in modern culture, whether it be in magazines, advertisements, or home decor.

The Venus de Milo, as one of the world's most recognized artworks, has often been referenced in popular culture.

A common comedic gag is depicting how the statue allegedly lost its arms. In 1960, Charlie Drake performed a comedy sketch which showed museum employees accidentally breaking off the arms while packing it.[46] The 1964 film Carry On Cleo similarly featured a skit which purported to show how the statue lost its arms. In the 1997 Disney film Hercules, the title character skips a stone and inadvertently breaks both arms off the statue.

A plot to steal the statue is at the center of the 1966 spoof spy film The Last of the Secret Agents?, starring Marty Allen and Steve Rossi.

The Venus de Milo is often featured and parodied in television shows, such as The Tick episode "Armless but Not Harmless", in which villains "Venus and Milo" rob an art museum, and the BBC sitcom Only Fools and Horses, where Del Boy shows Rodney a model of the statue claiming there are sick-minded people in the world who would make such a statue of a disabled person.

See also

Notes

References

- Curtis 2003, p. xvii.

- Hinz 2006.

- "statue; Vénus de Milo". Musée du Louvre. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- Maggidis 1998, p. 177.

- Kousser 2005, p. 238.

- Curtis 2003, p. xii.

- Curtis 2003, p. 189.

- Kousser 2005, p. 234.

- Kousser 2005, p. 239.

- Kousser 2005, p. 230.

- Curtis 2003, pp. 6–7.

- Curtis 2003, p. 16.

- Kousser 2005, p. 231.

- Curtis 2003, pp. 75–77.

- Kousser 2005, p. 236.

- Kousser 2005, p. 233.

- Maggidis 1998, p. 176.

- Curtis 2003, pp. 23–25.

- Kousser 2005, p. 232.

- Curtis 2003, p. 169.

- Curtis 2003, pp. 14–15.

- Curtis 2003, pp. 154–156.

- Prettejohn 2006, p. 230.

- Prettejohn 2006, pp. 232–234.

- Maggidis 1998, pp. 194–195.

- Prettejohn 2006, p. 240.

- Maggidis 1998, p. 192.

- Maggidis 1998, p. 196.

- Kousser 2005, pp. 235–236.

- Kousser 2005, p. 227.

- Hamiaux 2017, n. 24.

- Martinez 2022, p. 49.

- Martinez 2022, p. 46.

- Suhr 1960, p. 259.

- Maggidis 1998, p. 182.

- Kousser 2005, p. 235.

- Hamiaux 2017, p. 65.

- Bonazzoli, Francesca; Robecchi, Michele (2014). Mona Lisa to Marge: How the World's Greatest Artworks Entered Popular Culture. New York: Prestel. p. 32. ISBN 978-3791348773.

- "Saviour of France's art: how the Mona Lisa was spirited away from the Nazis". The Guardian. 22 November 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

On 25 August 1939, Jaujard closed the Louvre for three days, officially for repair work. For three days and nights, hundreds of staff, art students and employees of the Grands Magasins du Louvre department store carefully placed treasures in white wooden cases.

- Simon, Matila (1971). The Battle of the Louvre: The Struggle to Save French Art in World War II. pp. 123–124.

- Martinez 2022, p. 7.

- "Venus de Milo with Drawers (and PomPoms)". archive.thedali.org. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Brent, Burt (2008). "The Reconstruction of Venus: Following Our Legacy". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 121 (6): 2170–2171. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e318170a7b6.

- Diehn, Sonya Angelica (1 December 2011). "Greece Pursues Venus Defamation Case". Courthouse News Service. Archived from the original on 7 December 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- "Griechisches Gericht spricht Focus – Journalisten frei" [Greek Court acquits Focus journalists]. Burda Newsroom (in German). 3 April 2012. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012.

- "Charlie Drake's Christmas Show". 26 December 1960. p. 25 – via BBC Genome.

Sources

- Curtis, Gregory (2003). Disarmed: The Story of the Venus de Milo. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0375415234. OCLC 51937203.

- Hamiaux, Marianne (2017). "Le type statuaire de la Venus de Milo". Revue archéologique. 1 (63).

- Hinz, Berthold (2006). "Venus de Milo". Brill's New Pauly: Classical Tradition. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e15308860.

- Kousser, Rachel (2005). "Creating the Past: The Vénus de Milo and the Hellenistic Reception of Classical Greece". American Journal of Archaeology. 109 (2): 227–250. doi:10.3764/aja.109.2.227. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 40024510. S2CID 36871977.

- Maggidis, Christofilis (1998). "The Aphrodite and the Poseidon of Melos: A Synthesis". Acta Archaeologica. 69.

- Martinez, Jean-Luc (2022). La Vénus de Milo. Paris: Louvre éditions. ISBN 9-788412-154832.

- Prettejohn, Elizabeth (2006). "Reception and Ancient Art: The Case of the Venus de Milo". In Martindale, Charles; Thomas, Richard (eds.). Classics and the Uses of Reception. Blackwell.

- Suhr, Elmer G. (1960). "The Spinning Aphrodite in Sculpture". American Journal of Archaeology. 64 (3). JSTOR 502465.

- Venus de Milo: The Oxford Dictionary of Art

- James Grout, Venus de Milo, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

External links

- "Ideal Greek Beauty: Venus de Milo and the Galerie des Antiques", Louvre Museum

- 3D model of Venus de Milo, produced from the plaster cast at Skulpturhalle Basel

- "How the Venus de Milo got so famous", Vox

.jpg.webp)