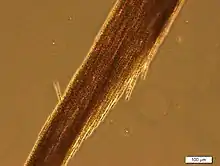

Aphanizomenon flos-aquae

Aphanizomenon flos-aquae is a brackish and freshwater species of cyanobacteria found around the world, including the Baltic Sea and the Great Lakes.

| Aphanizomenon flos-aquae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Cyanobacteria |

| Class: | Cyanophyceae |

| Order: | Nostocales |

| Family: | Aphanizomenonaceae |

| Genus: | Aphanizomenon |

| Species: | A. flos-aquae |

| Binomial name | |

| Aphanizomenon flos-aquae (Linnaeus) Ralfs ex Bornet & Flahault, 1888 | |

Ecology

Aphanizomenon flos-aquae can form dense surface aggregations in freshwater (known as "cyanobacterial blooms").[1] These blooms occur in areas of high nutrient loading, historical or current.

Toxicity

Aphanizomenon flos-aquae has both toxic and nontoxic forms.[2] Most sources worldwide are toxic, containing both hepatic and neuroendotoxins.[3]

Most cyanobacteria (including Aphanizomenon) produce BMAA, a neurotoxin amino acid implicated in ALS/Parkinsonism.[4][5][6]

Toxicity of A. flos-aquae has been reported in Canada,[7] Germany[8][9] and China.[10]

Aphanizomenon flos-aquae is known to produce endotoxins, the toxic chemicals released when cells die. Once released (lysed), and ingested, these toxins can damage liver and nerve tissues in mammals. In areas where water quality is not closely monitored, the World Health Organization has assessed toxic algae as a health risk, citing the production of anatoxin-a, saxitoxins, and cylindrospermopsin.[11] Dogs have been reported to have become ill or have fatal reactions after swimming in rivers and lakes containing toxic A. flos-aquae.

Microcystin toxin has been found in all 16 samples of A. flos-aquae products sold as food supplements in Germany and Switzerland, originating from Lake Klamath: 10 of 16 samples exceeded the safety value of 1 μg microcystin per gram.[12] University professor Daniel Dietrich warned parents not to let children consume A. flos-aquae products, since children are even more vulnerable to toxic effects, due to lower body weight, and the continuous intake might lead to accumulation of toxins. Dietrich also warned against quackery schemes selling these cyanobacteria as medicine against illnesses such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, causing people to omit their regular drugs.

Medical research

A Canadian study studying the effect of A. flos-aquae on the immune and endocrine systems, as well as on general blood physiology, found that eating it had a profound effect on natural killer cells (NKCs).[13] A. flos-aquae triggers the movement of 40% of the circulating NKCs from the blood to tissues.

As a food supplement

Some compressed tablets of powdered A. flos-aquae cyanobacteria (named as "blue green algae") have been sold as food supplements, notably those filtered from Upper Klamath Lake in Oregon.[14]

See also

References

- "Cyanobacteria/Cyanotoxins". US EPA. 2 January 2014. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Carmichael, Wayne W. (January 1994). "The Toxins of Cyanobacteria". Scientific American. 270 (1): 78–86. Bibcode:1994SciAm.270a..78C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0194-78. ISSN 0036-8733. PMID 8284661.

- Karina Preußela, Fastnera Jutta; Federal Environmental Agency, FG II 3.3, Corrensplatz 1, 14195 Berlin, Germany; Department of Limnology of Stratified Lakes, Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Alte Fischerhütte 2, 16775 Stechlin, Germany; 15 October 2005

- Cox, PA; Sacks, OW (2002). "Cycad neurotoxins, consumption of flying foxes, and ALS-PDC disease in Guam". Neurology. 58 (6): 956–9. doi:10.1212/wnl.58.6.956. PMID 11914415. S2CID 12044484.

- Holtcamp W (2012). "The Emerging Science of BMAA: Do Cyanobacteria Contribute to Neurodegenerative Disease?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 120 (3): 110–16. doi:10.1289/ehp.120-a110. PMC 3295368. PMID 22382274.

- Jonasson S, Eriksson J, Berntzon L, Spácil Z, Ilag LL, Ronnevi LO, Rasmussen U, Bergman B (2010). "Transfer of a cyanobacterial neurotoxin within a temperate aquatic ecosystem suggests pathways for human exposure". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (20): 9252–7. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.9252J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914417107. PMC 2889067. PMID 20439734.

- Saker ML, Jungblut AD, Neilan BA, Rawn DF, Vasconcelos VM (October 2005). "Detection of microcystin synthetase genes in health food supplements containing the freshwater cyanobacterium Aphanizomenon flos-aquae" (PDF). Toxicon. 46 (5): 555–62. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.06.021. PMID 16098554.

- Preussel K, Stüken A, Wiedner C, Chorus I, Fastner J (February 2006). "First report on cylindrospermopsin producing Aphanizomenon flos-aquae (Cyanobacteria) isolated from two German lakes". Toxicon. 47 (2): 156–62. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.10.013. PMID 16356522.

- Toxin content and cytotoxicity of algal dietary supplements Archived 19 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, by Dr. Alexandra H. Heussner

- Chen Y, Liu J, Yang W (May 2003). "Effect of Aphanizomenon flos-aquae toxins on some blood physiological parameters in mice". Wei Sheng Yan Jiu [Journal of Hygiene Research] (in Chinese). 32 (3): 195–7. PMID 12914277.

- World Health Organization (2006). Guidelines for drinking-water quality. First addendum to third edition. Volume 1. Recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154674-4. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017.

- "AFA-Algen – Giftcocktail oder Gesundheitsbrunnen?" [AFA algae - toxic cocktail fountain or health?] (Translated from German). Universität Konstanz. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Effects of the Blue Green Algae Aphanizomenon flos-aquae on Human Natural Killer Cells. – Chapter 3.1 of the IBC Library Series, Volume 1911, Phytoceuticals: Examining the health benefit and pharmaceutical properties of natural antioxidants and phytochemicals

- Spolaore P, Joannis-Cassan C, Duran E, Isambert A (February 2006). "Commercial applications of microalgae". Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 101 (2): 87–96. doi:10.1263/jbb.101.87. PMID 16569602. S2CID 16896655.

External links

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. "Aphanizomenon flos-aquae". AlgaeBase. World-wide electronic publication, National University of Ireland, Galway.