Antrectomy

Antrectomy, also called distal gastrectomy, is a type of gastric resection surgery that involves the removal of the stomach antrum to treat gastric diseases causing the damage, bleeding, or blockage of the stomach.[1][2] This is performed using either the Billroth I (BI) or Billroth II (BII) reconstruction method. Quite often, antrectomy is used alongside vagotomy to maximise its safety and effectiveness.[3] Modern antrectomies typically have a high success rate and low mortality rate, but the exact numbers depend on the specific conditions being treated.[4]

| Antrectomy | |

|---|---|

| |

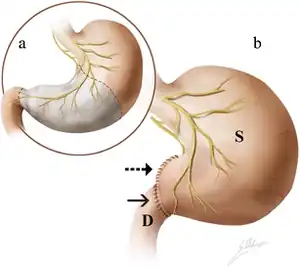

| a. Antrectomy is performed along the dashed lines, with the removal of stomach parts highlighted in gray. b. An end-to-end anastomosis is created between the remnant stomach (S) and duodenum (D). |

The history of antrectomy traces back to the 19th century, starting with the first successful gastric resection in 1810. Since then, antrectomy has undergone a magniftude of changes, where development in the field continues to this day. Even though antrectomy paired with vagotomy and anastomosis is now the established gold standard, its side effects and clinical relevance remains a controversial subject. With advancements in alternative surgeries and other non-invasive treatments, antrectomy is less common nowadays.

Purpose

Generally, an antrectomy is performed to treat bleeding and blockage of the stomach.[2] This could be caused by a variety of gastric disorders, including:

- Peptic ulcer disease (PUD): The disease is characterized by ulcers developed either by impaired mucus protection or an excess of gastric acid production.[5] Antrectomy could either lead to the reduction of gastric acid levels or the removal of the peptic ulcer altogether. Antrectomy is rarely warranted in this case since PUD rarely recurs and is usually manageable via medications.[1]

- Zollinger–Ellison syndrome: The condition features excessive gastric acid production.[6] Antrectomy removes gastrin-producing G-cells in the stomach antrum, in turn reducing gastric acid levels.

- Gastric cancer: Antrectomy could remove gastric tumors developing in the antrum.[1]

- Gastric antral vascular ectasia syndrome (GAVE): The disease is characterized by excessive bleeding in the stomach. By removing the bleeding site and reconnecting the upper stomach with the intestines, antrectomy controls chronic bleeding and ensures gastric continuity.[1]

- Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO): It is a condition where the passage between the stomach and the duodenum is blocked. Removal of the blocked stomach parts by antrectomy could ensure continuity of the gastrointestinal system.[1]

- Penetrative wounds in the duodenum, stomach, or pancreas: The removal of devitalized tissue by antrectomy could prevent continuous bleeding and inflammation from wound infection.[1]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of stomach disorders begins with the examination of the patient’s history and family history, and supplemented with a physical exam.[7] Old age and recent significant weight loss would suggest the possibility of gastric cancer.[7] A family history of duodenal or gastric ulcers would require the patient to describe the type of discomfort he/she is experiencing.[7] Different stomach disorders manifest pain at different time periods.[7]

The most common diagnostic tests for stomach disorders include endoscopy, double-contrast barium x-ray study of the upper GI tract, and the detection of H. pylori infection.[7]

Surgical procedure

A midline epigastric incision is first made from the xiphoid process of the sternum to the umbilicus.[8] The opening can be widened by extending the incision inferiorly.[8] When the abdominal organs are exposed, thorough exploration is undertaken to assess the extent of disease and, in the case of stomach cancer, to confirm resectability.[8]

Two surgical methods can then be used to perform antrectomy:[9]

- Billroth I (BI) reconstruction method: a gastroduodenostomy with end-to-end or end-to-side surgical anastomosis; the duodenal passage is preserved and remains intact.[9]

- Billroth II (BII) reconstruction method: a gastrojejunostomy with end-to-side surgical anastomosis.[9]

With end-to-end surgical anastomosis

The gastrocolic ligament of the greater omentum is incised at the middle of the greater curvature of the stomach, which opens the lesser sac.[9] The dissection for gastric ulcers can be done between the gastroepiploic vessels and the gastric wall.[9] In carcinoma, the greater omentum corresponding to the extent of the resection of the greater curvature must be removed at the same time.[9] The incision continues along the greater curvature towards the duodenum.[9] Near the pylorus of the stomach, the greater omentum becomes thick and divides into the front and back layer.[9] Dissection should be continued bluntly and the right gastroepiploic vessels running between the two layers are ligated.[9]

The Kocher manoeuver is used at a position above or just below the descending (second) part of the duodenum from a lateral direction.[9] The duodenum is mobilised to achieve a good general exposure, which facilitates the subsequent gastroduodenostomy.[9] The preparation of the free superior (first) part of the duodenum is then continued.[9] By stretching the stomach, the dissection proceeds along the greater curvature toward the left medial duodenal wall, then toward the back wall, and finally toward the lateral duodenal wall of the superior part as far as the beginning of the hepatoduodenal ligament.[9] This way, 3 to 5 cm of the back wall of the duodenum can be exposed.[9]

Dissection is then performed along the lesser curvature of the stomach.[9] The right gastric artery is divided between clamps and ligated.[9] The front and back layer of the lesser (gastrohepatic) omentum is severed individually.[9]

The actual resection starts with the cutting of the duodenum between holding or guy sutures.[9] The duodenum is temporarily closed with a sponge; the resection borders of the stomach are then determined.[9]

A sewing instrument facilitates the final step of stomach removal.[9] The incision follows at an angle of 45 degrees to the lesser curvature.[9] The staple line can, but need not, be oversewn.[9] After removal of the distal portion (including the antrum and the pylorus) of the stomach, a clamp is fitted at right angles to the greater curvature.[9] The clamp is pushed far enough orally (towards the mouth) for the removal level to correspond in size to the duodenal lumen.[9] The remaining aboral (away from the mouth) end is cut off after stay sutures are placed at each cut edge.[9] The anastomosis should be performed without clamps.[9]

The end-to-end gastroduodenostomy is accomplished by anastomosing the duodenum to the end of the greater curvature.[9] For this purpose, the two cut surfaces are placed adjacent to each other and two corner stitches are placed, starting at the stomach through the seromuscular layers with tangential grasping of the mucosa.[9] At the duodenum, this stitch is done from inside to outside.[9] The corner suture at the lesser curvature is tied, whereas the suture on the opposite side is left open.[9] The back wall is reconstructed by interrupted back stitches.[9] These stitches start through all layers of the back wall at the cut edge of the lesser curvature from inside to outside and go through all layers of the posterior wall of the duodenum from outside to inside.[9] The suture is led back grasping only the mucosa, first of the duodenum and then of the stomach.[9] Knotting these sutures leads to an exact coaptation, especially at the level of the mucosa.[9] The front wall is best closed with one row of interrupted sutures through all layers with tangential stitches of the mucosa with the same technique as the corner stitches.[9] Special attention must be paid to the Jammerecke (angle of sorrow) on the lesser curvature.[9]

Finally, the anastomosis is checked for patency with the thumb and index finger.[9] The position of the stomach tube is also checked to ensure it crosses the anastomosis.[9] A double-lumen gastric tube is placed across the anastomosis for 2 to 3 days, allowing early enteral nutrition via the distal lumen.[9]

With end-to-side surgical anastomosis

In difficult duodenal ulcers, it can be impossible to preserve enough duodenal wall to be able to construct a tension-free anastomosis.[9] In this situation, it is safer to staple close the duodenum and reconstruct the intestinal passage by end-to-side anastomosis.[9] For this purpose, the stomach is removed as previously described; the dissected stomach lumen is then anastomosed onto the front wall of the duodenum.[9]

Usually, an oblique incision should be made on the duodenal front wall so that the incision level starts from oral–medial and goes to aboral–lateral.[9] The suturing technique is the same as for the end-to-side anastomosis.[9] In technically difficult duodenal stump closures, additional coverage of the stump with the back wall of the stomach can be obtained.[9]

Billroth II (BII) reconstruction method

_CRUK_281.svg.png.webp)

Both the left gastric and left gastroepiploic artery are preserved in this method, although the resection is more extended.[9]

At the oral margin of the dissection line, usually covering two-thirds of the stomach, the resection is completed by transverse application of a linear stapler in a way that the complete stomach is divided between one stapler application.[9] The staple line can be oversewn.[9]

The first or second loop of the jejunum is then mobilised and placed tension-free and in a retrocolonic fashion opposite the greater curvature of the remaining stomach.[9] The loop should be long enough and should have a Braun jejunojejunostomy between the ascending and the descending loop.[9]

The last 4 to 5 cm of the stapler line towards the greater curvature should be excised with the help of an electrocautery device in order to form a slim opening for the subsequent gastrojejunostomy.[9] Stay sutures are placed on both sides of the anastomosis.[9] The jejunum is incised with the electrocautery device opposite the mesentery.[9]

The gastrojejunostomy is performed by single interrupted sutures with resorbable suture material and, as the anastomosis cannot be turned, the back wall is sutured by interrupted mattress sutures and the front wall by extramucosal interrupted sutures.[9] Alternatively, continuous suturing with a monofilament resorbable thread on both sides of the anastomosis is possible.[9] Before finalisation of the front wall, a double-lumen gastric tube is placed distally to the anastomosis, allowing early enteral nutrition.[9] In order to prevent enterogastric (bile) reflux, the formation of a jejunojejunostomosis (Braun anastomosis), side-to-side, and 30 cm aborally of the gastrojejunostomy is mandatory.[9] This anastomosis can be either hand-sewn (interrupted or continuous technique, resorbable suture material) or stapled.[9]

Supplementary operations

Supplementary operations can be applied alongside antrectomy to maximise its success and effectiveness. One commonly performed is vagotomy (the removal of the vagus nerve), since the vagus nerve also plays a key role in gastric juice regulation. While performed separately, vagotomy and antrectomy reduce stomach acid secretion by up to 60%.[10] Combining both practices could reduce stomach acid secretion by up to 80% through an additive effect.[10] In some cases, antrectomy can be used alongside laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy to facilitate weight loss.[11] Yet, the clinical relevance of including antrectomy in this procedure remains to be seen.[11]

Outcome

The success rate of antrectomy is dependent on the rationale of the surgery. For example, antrectomies that are done to overcome peptic ulcer disease (PUD) have a 95% success rate, while the percentage is higher for gastric antral vascular ectasia syndrome (GAVE).[4] However, antrectomies that deal with gastric cancer or penetrative wounds are not as successful.[4] One possible explanation is that these symptoms are usually more severe and therefore harder to treat, no matter the kinds of surgery used.[4]

Nowadays, the mortality rates for antrectomy are typically low. The death rate of antrectomy for ulcer treatment is 1-2%, while it is 1-3% for gastric cancer.[4] Similarly, the chances of developing complications after surgery depend on the reason for the surgery and the type of complication in question. For example, antrectomy for peptic ulcers has a 1-5% chance for the condition to recur, a 12% chance of developing diarrhea, and a 30-35% chance of developing Dumping syndromes.[4]

History

The clinical basis of antrectomy was laid in the 19th century with the birth of its father - gastric resection. The first attempt at gastric resection was by German professor and surgeon Christian Michaelis, whose experiment on removing pylorus in animals to resolve gastric obstruction failed.[12] In 1810, his student Daniel Merrem successfully performed the resection of the distal stomach and reconnected the duodenum to the stomach in animal experiments.[12] The first clinical attempt of a gastric resection occurred in 1879 by French surgeon Jules-Émile Péan, who unsuccessfully carried out a pylo-rectomy for a cancer patient.[12] This was followed by the attempt of Polish surgeon Ludwik Rydygier, whose gastric resection also ended in the death of his patient.[12] It was not until 1881 was the first successful gastrectomy carried out by German physicianTheodor Billroth. Billroth first tested gastrectomy surgery on animals in an experiment known as ‘Billroth I gastrectomy’, which resulted in the long-term survival of two out of seven dogs.[12] This eventually led to the first successful gastric resection in a patient with stomach cancer, in which the duodenum was cut 1.5 cm away from the tumor and reattached to the stomach with carbolized silk.[12] The practice was then quickly applied to Billroth’s clinics, with 19 successful operations out of 41 gastrectomies by 1890.[12]

Following the success of the first gastric resection, the birth of antrectomy is attributed to a better understanding of the gastrointestinal system in the early 20th century. Upon the discovery of gastrin by John S. Edkins in 1906, E. Klein published the first report combining vagotomy with gastrectomy to ease symptoms of excessive gastric juice secretion.[13] By 1946, American physicians Farmer and Smithwick performed the first vagotomy with hemigastrectomy (the removal of one-half of the stomach).[13] In the following year, Herrington of Vanderbilt University similarly combined vagotomy with the removal of the lower stomach to improve operational effectiveness, sparking the earliest resemblance to the antrectomy performed today.[13] During the same period, other variations of Billroth's gastrectomy such as concurrent gastrojejunal anastomosis were also transforming the landscape of gastrectomy, with the most notable contributions by surgeons Hofmeister, Polya, von Haberer, and Finsterer.[12] These variations influenced the way antrectomy is practiced, specifically the type of surgeries that antrectomy is paired with.

In the subsequent decades, antrectomy continued to evolve with advancements in surgical techniques. The 1950s marked the popularization of diagnostic and operational laparoscopy in hospitals and medical training.[14] This meant that antrectomy could be performed in a minimally invasive manner. However, complications such as diarrhea in antrectomy continue to be a problem, with a 1952 edition of The Lancet Review commenting, 'fashions in the treatment of peptic ulcer come and go, and the surgical problem remains unsolved.'[15] Hence the 1950s and 60s also marked the era of comparative studies of stomach surgery in an attempt of finding an effective method with the least side effects. Most notably, the 1968 Leads-York controlled trial published by The British Medical Journal found that the combination of vagotomy and gastrectomy is superior to other forms of surgery such as gastroenterostomy on the Visick grading (scoring system to quantify the symptomatic outcome of peptic ulcer surgery).[16]

The decades leading up to the present featured shifting applications of antrectomy. With the commercialization of acid-reducing medications such as antacids in the late 1970s, the incidence and prevalence of gastric ulcers fell, hence reducing the need for antrectomy. At the same time, British physician David Cowley became the first person to diagnose and treat pseudo-Zollinger-Ellison syndromes (stomach ulceration and excessive gastric acid production) using antrectomy and vagotomy.[17] In the subsequent decades, a better understanding of the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome led to antrectomy becoming one of the key treatment methods for the ailment.

Despite this, advent of newer non-invasive methods of resolving gastric disorders have made antrectomy less relevant nowadays. By 2003, antrectomy is no longer recognized as the first-line treatment for gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) and peptic ulcer disease.[4]

Benefits

Antrectomy can reduce acid secretion in PUD and remove premalignant tissue to reduce gastric cancer odds.[1] This offers a permanent method that has a 95% success rate. It also alleviates pain, hemorrhage, and anemia from recurring stomach ulcers. For localized cancer cases, antrectomy can eliminate early-stage cancer in the third (lower) portion of the stomach. Moreover, antrectomy is able to treat PUD and GOO by the removal of malignant tissues which controls early-stage gastric cancer while retaining sufficient portions of the stomach for adequate digestion and nutrition uptake. Furthermore, treating obesity with antrectomy is also becoming more common. Antrectomy is also the immediate and only approach to reconstructing organs from injuries such as stabbing in the lower portion of the stomach.

Risks and complications

Antrectomy results in the removal of parts of the stomach, reducing the functions of a normal stomach. Around 30% of patients develop Dumping syndrome, a condition where food entering the stomach enters the intestines prematurely due to a partially removed stomach not maximizing its digestive function. It causes heartburn, nausea, fatigue, and vomiting after meals.[4] In addition, other side effects include dysphagia, which is when digestive juices in the duodenum flow upward to the esophagus, thus esophageal lining is irritated. Diarrhea is common, especially in patients who had vagotomy in addition to an antrectomy because the damage of nerves to the liver and gallbladder causes excess bile salt release.

Due to a decrease in gastric function, patients have to adjust to a diet composed of high protein and low carbohydrates.[4] They must take more liquids when eating and have small and frequent meals. The decreased gastric function also leads to malabsorption and malnutrition, especially for iron, folate, and calcium because acid is important for assimilating these substances.[18] Therefore, weight loss due to decreased food intake and malnutrition is common in patients in recovery, especially in elderly patients. Additionally, Bezoar development obstruction of the digestive tract is also seen in postoperative patients because the fiber and more solid food are not fully digested by the shrunk stomach.[4]

Other than side effects, the success of antrectomy in treating the target condition is also debatable. Antrectomy removing a part of the stomach does not treat later-stage cancer.[19] For PUD patients, antrectomy alone could still cause the recurrence of gastric ulcers,[18] even if paired with a vagotomy. Leakage from anastomosis of the resected stomach and small intestines can also occur in some patients

Alternatives and medication

Antrectomy is an invasive surgery that is only performed when patients experience bleeding, perforation, obstruction, and malignancy. Treatment alternatives are based on their diagnosis.

For gastric outlet obstruction (GOO), balloon dilation is a new option for treatment. Endoscopic stenting is also used as an alternative but due to the chance of re-obstruction and stent migration,[20] it is usually performed on patients with shorter life expectancies.

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD)

Antrectomy is often not considered a first-line treatment for PUD due to the high success rate of medication and antibiotics.[21] Suitable candidates are those who failed to recover from treatment with over-the-counter NSAID and have severe damage to the stomach lining.[22]

“Triple therapy” is a combination of antibiotics to rid bacterium, protect the stomach lining and reduce stomach acid production.[4] The drug types include:

- Sucralfate, a compound of sucrose, and aluminum that coats ulcers allowing eroded tissues to recover.

- Antibiotics to treat H. pylori if it is detected, such as Bismuth subsalicylate which can also protect the stomach lining

- NSAIDS (Prostaglandins) to reduce pain and protect the stomach lining and reduce acid secretion. Misoprostol is the most effective choice

Other medications for managing PUD

Antacids are used to neutralize gastric acid but require a large dose which could lead to diarrhea.[23] Histamine (H2) blockers reduce gastric acid by blocking the H2 receptors, a safe option for patients.[23] Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) block major pathways of acid production. It is more specific than H2 blockers and is considered a “gold standard”.[23] Examples are omeprazole and lansoprazole.

Cancer

For cancer, chemotherapy is the most common alternative to antrectomy. Antrectomy is suitable for early-stage gastric cancer as complete removal can stop cancer spread. With advancements in endoscopic surgeries, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is a non-invasive choice that is safer than antrectomy for small tumor removals in the distal portion of the stomach.[19] For late-stage cancer where malignancy is spread to other organs, chemotherapy is preferred as surgery cannot eliminate cancer.[4] Cancer patients’ condition is also considered when making surgical decisions.

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO)

Other surgeries can manage GOO. Surgical approaches are decided based on the patient’s condition and the development of the condition. Enteral stents are used to expand the obstruction of the pylorus. Medication is used to protect the stomach lining.

Other symptom-managing choices

Other medications including acupuncture, ayurvedic medication, and herbal preparations used based on the individual’s physique are given as non-invasive treatments in Asian countries and have successful outcomes.[4] To manage pain from ulcer and obstruction symptoms, herbalist approaches include licorice, bupleurum, fennel, fenugreek, slippery elm, and marshmallow root.[4]

Recent development

With advancements in endoscopy, traditional antrectomy is a less popular surgical choice for gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) and peptic ulcer disease (PUD).[20]

In the past, 89-90% of ulcer-related GOO patients required surgery.[24] As the development of endoscopic procedures advances, recent reports suggest that endoscopic balloon dilation is an effective treatment option for GOO and PUD.

For Type I, II, and III ulcers, robot-assisted gastric antrectomy and vagotomy are gaining popularity. This method reduces blood loss and length of stay but the operation duration is longer.[21] It carries out exact dissections in a scarred stomach and duodenum and offers magnification and smooth articulation of instruments.[25]

Robotic antrectomy first involves a dissection along the greater curvature of the stomach, from the pylorus to the cephalad followed by mobilizing the lesser curvature and ligating the right gastric artery.[25] The duodenal bulb is removed from the pancreas.[25] At this point, the proximal transection should extend from the indentation of the lesser curvature to the terminal branch of the right gastroepiploic artery on the greater curvature.[25] The distal transection should be done on the duodenum.[25] The antrectomy ends by creating an anastomosis for gastrointestinal continuity, usually gastroduodenal or gastrojejunal anastomosis.[25]

As robotic antrectomy is not popularized in most hospitals, intracorporeal antrectomy and anastomosis are the most common for tumor removal and curing complicated PUD as it is comparatively less invasive and minimizes blood loss. The first case of single-incision laparoscopic antrectomy for type I gastric neuroendocrine tumor was reported in 2021.[26]

In recent years, antrectomy has been used to control obesity.[27] There are debates on the safety and efficiency of this procedure regarding the distance from the pylorus of which the resection takes place. Trials and reviews have been done on exploring the postoperative effects, nausea and vomiting, and chance of leakage from anastomosis when antrectomy is done 2 cm or less from the pylorus.[28] Developments aim to reduce the stomach volume in obese patients while retaining digestive function and ensuring safety.

References

- Hiam, Deirdre (2020). The Gale Encyclopedia of Surgery and Medical Tests (4th ed.). America: Gale. p. 126. ISBN 978-0028666518.

- "Antrectomy with Vagotomy - What You Need to Know". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- "Anastomosis Information | Mount Sinai - New York". Mount Sinai Health System. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- Mishra, Dr R. K. "Antrectomy". www.laparoscopyhospital.com. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- "Peptic ulcer - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- "Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2020-07-20. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- The Gale Encyclopedia of Surgery and Medical Tests (4th ed.). Gale Research Inc. March 20, 2020. ISBN 978-0028666518.

- Grant, C. N. (March 8, 2023). "Antrectomy (Distal Gastrectomy) Technique". Medscape.

- Fischer, Josef E.; Ellison, E. Christopher; Upchurch, Jr., Gilbert R.; Galandiuk, Susan; Gould, Jon C.; Klimberg, V. Suzanne; Henke, Peter; Hochwald, Steven N.; Tiao, Gregory M.; Slavin, Erica N. (May 18, 2018). Fischer's Mastery of Surgery (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1469897189.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Leth, R.; Elander, B.; Fellenius, E.; Olbe, L.; Haglund, U. (December 1984). "Effects of proximal gastric vagotomy and antrectomy on parietal cell function in humans". Gastroenterology. 87 (6): 1277–1282. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(84)90193-8. ISSN 0016-5085. PMID 6092196 – via PubMed.

- Yu, Qian; Saeed, Kashif; Okida, Luis Felipe; Gutierrez Blanco, David Alejandro; Lo Menzo, Emanuele; Szomstein, Samuel; Rosenthal, Raul (March 2022). "Outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with and without antrectomy in severely obese subjects. Evidence from randomized controlled trials". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 18 (3): 404–412. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2021.11.016. ISSN 1878-7533. PMID 34933811. S2CID 244472108.

- Macintyre, I. M. (May 2000). "Peptic ulcer surgery - an obituary". Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 30 (2): 158–163. ISSN 0953-0932. PMID 11624510.

- Blalock, J. B. (March 1981). "History and evolution of peptic ulcer surgery". American Journal of Surgery. 141 (3): 317–322. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(81)90187-2. ISSN 0002-9610. PMID 7011076.

- Says, Daniel Tsin (2010-05-19). "Laparoscopic Surgery History". News-Medical.net. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- McConville, Sharon; Crookes, Peter (Jan 2007). "The History of Gastric Surgery: the Contribution of the Belfast School". Ulster Medical Journal. 76 (1): 31–36. PMC 1940305. PMID 17288303.

- Macintyre, I. M. (August 2000). "Peptic ulcer surgery - an obituary (part two)". Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 30 (3): 245–251. ISSN 0953-0932. PMID 11640174.

- Kaplan, Edwin L.; Tanaka, Reiko; Ito, Koichi; Younes, Nidal; Friesen, Stanley R. (October 1994). "The discovery of the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome". Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 1 (5): 509–516. doi:10.1007/BF01211912. ISSN 0944-1166.

- "Stomach Ulcer Surgery and its Complications (Peptic Ulcer) | Doctor". patient.info. 26 August 2022. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- "Surgery for Stomach Cancer & Possible Side Effects". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- Miller, Amie; Schwaitzberg, Steven (2014-03-01). "Surgical and Endoscopic Options for Benign and Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction". Current Surgery Reports. 2 (4): 48. doi:10.1007/s40137-014-0048-z. ISSN 2167-4817. S2CID 71372592.

- Laparoscopic antrectomy and vagotomy for stenotic pyloric peptic ulcer, retrieved 2023-03-28

- "Antrectomy (Distal Gastrectomy): Background, Indications, Contraindications". reference.medscape.com. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- "Peptic Ulcer Disease Treatment". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2021-10-01. Retrieved 2023-03-28.

- Weiland, Douglas; Dunn, Daniel H.; Humphrey, Edward W.; Schwartz, Michael L. (1982-01-01). "Gastric outlet obstruction in peptic ulcer disease: An indication for surgery". The American Journal of Surgery. 143 (1): 90–93. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(82)90135-0. ISSN 0002-9610. PMID 7053661.

- Moghul, Fazaldin; Ali, Abubaker A. (2022), Kudsi, Omar Yusef; Grimminger, Peter P. (eds.), "Robotic Truncal Vagotomy and Antrectomy", Atlas of Robotic Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 91–101, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-86578-8_10, ISBN 978-3-030-86578-8, S2CID 244049139, retrieved 2023-03-28

- Kitadani, Junya; Ojima, Toshiyasu; Hayata, Keiji; Katsuda, Masahiro; Tominaga, Shinta; Fukuda, Naoki; Motobayashi, Hideki; Nagano, Shotaro; Nakamura, Masaki; Yamaue, Hiroki (2021-01-12). "Single-incision laparoscopic antrectomy for type I gastric neuroendocrine tumor: a case report". Surgical Case Reports. 7 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/s40792-021-01109-7. ISSN 2198-7793. PMC 7803843. PMID 33433761.

- Yu, Qian; Saeed, Kashif; Okida, Luis Felipe; Gutierrez Blanco, David Alejandro; Lo Menzo, Emanuele; Szomstein, Samuel; Rosenthal, Raul (March 2022). "Outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with and without antrectomy in severely obese subjects. Evidence from randomized controlled trials". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 18 (3): 404–412. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2021.11.016. ISSN 1878-7533. PMID 34933811. S2CID 244472108.

- Mayir, Burhan (June 2022). "Starting Antrectomy in Less than 2 cm from Pylorus at Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy". Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan: JCPSP. 32 (6): 701–705. doi:10.29271/jcpsp.2022.06.701. ISSN 1681-7168. PMID 35686399. S2CID 249543842.