Anthony Haswell (printer)

Anthony Haswell (6 April 1756 – 26 May 1816) was an English immigrant to New England, where he became a newspaper, almanac, and book publisher, the Postmaster General of Vermont and one of the Jeffersonian printers imprisoned under the Sedition Act of 1798.

Anthony Haswell | |

|---|---|

| Born | 6 April 1756 Portsmouth, England |

| Died | 26 May 1816 (aged 60) |

| Occupation(s) | printer, journalist, postmaster |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | William Pritchard, Anthony Johnson, Elizabeth, David Russel, Nathan Baldwin, Mary, William, Eliza, Susanna, Lydia, Eliza, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, John Clark, and Charles Salem Haswell, Alvah Rice (adopted), Betsy Rice/Haswell (adopted) |

| Relatives | Susanna (Haswell) Rowson Robert Haswell |

Immigration and revolution

Anthony Haswell was born in or near Portsmouth, England, on 6 April 1756, the second son of shipwright William Haswell and his first wife Elizabeth Dawes.[1] The father had been employed at the royal dockyard, but in 1769 resigned his position with the intention of emigrating.[2] He took Anthony and his brother William with him to Boston and likely immediately apprenticed Anthony with a potter while young William trained as a shipwright under his father. Within a year, the father decided to return to England, apprenticing William to a Boston shipwright.[2] Anthony's brother would return to England for a visit on the eve of the Revolutionary War, the outbreak of which prevented his return to Boston, and he would serve for four decades in the Royal Navy.[2] Also in the Boston area at this time was his father's cousin, Customs Service officer and Royal Navy Lieutenant William Haswell, who had a young daughter Susanna Haswell (later Rowson) and son Robert Haswell.[1][2][3]

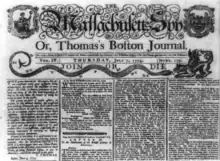

It is not known when, or under what circumstances, Anthony's first apprenticeship came to a premature end but in August 1771 he was apprenticed by Boston's Overseers of the Poor until the age of 21 to printer Isaiah Thomas,[2][3] who published the radical Massachusetts Spy at the Boston location currently occupied by the Union Oyster House. Anthony had witnessed the Boston Massacre and developed an interest in the politics of the time, becoming a member of the Sons of Liberty and composing ballads for the movement.[3] In April 1775 Thomas was forced to evacuate his press from Boston, moving to Worcester where publication continued,[3] but within a year Haswell bought his way out of his apprenticeship early. He served in the Revolutionary War although the details of this service have been lost.[2][3][4] During Thomas's own service, the paper was leased, and from August 1777 to June 1778 Anthony Haswell published it under the banner of Haswell's Massachusetts Spy. He would initiate a plan to buy the press from Thomas, but skyrocketing labor costs, problems acquiring materiel, and difficulties receiving timely payment from subscribers would force him to return the paper to Thomas, who then rehired Haswell as his assistant.[2]

In 1778 Anthony married Worcester native Lydia Baldwin and Haswell the next year worked for several weeks in Providence as a journeyman printer with the Providence Gazette, before moving his family to Hartford to work for the publisher of the Connecticut Courant. There he formed a partnership with Elisha Babcock and the two relocated to Springfield, where in 1782 they founded the Massachusetts Gazette.[2][3] The following spring, however, he was enticed by the government of Vermont to relocate to Bennington. He took the press by wagon to Bennington, and acquired his type by digging up a set that had been buried in Albany at the time of the French and Indian War.[2]

Vermont

Haswell arrived in Bennington in 1783, becoming the second printer in Vermont. He had been offered the postal franchise and was shortly appointed Postmaster General of Vermont, in which role he continued until Vermont's admission to the Union in 1791 placed the mail under Federal control.[5] He alternated with a Windsor colleague as official government printer. In Bennington, he and David Russell founded the Vermont Gazette, which Haswell published with several breaks until the time of his death. The pair built the state's first paper mill.[2] Haswell shortly gained a certain notoriety by publishing Ethan Allen's controversial deist tract, Reason, the Only Oracle of Man: Or, A Compendious System of Natural Religion in 1785. Over the following years he tried to extend his business, opening offices in Vergennes and Litchfield, Connecticut and founding the first Rutland newspaper, The Herald of Rutland, in 1792 only to have the printing office burn after just fourteen issues, dooming the project.[2][6] An attempt at a monthly magazine also failed.

Sedition

As the politics of the early Republic developed, Haswell fell into the camp of Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party, becoming one of the leading printers of the movement. As such, he was targeted under the Sedition Act of 1798. Specifically, following the arrest of Congressman Matthew Lyon, Haswell published an advertisement for a lottery intended to raise the fine levied against Lyon, decrying the "oppressive hand of usurped power" from a "hard-hearted savage."[7] Haswell also republished a claim made in Benjamin Franklin Bache's Philadelphia Aurora that the government had employed Tories.[8] Though in neither case was the offending text of his own composition, his long-standing Jeffersonian partisanship marked him for prosecution. As a result, he was arrested, taken from his house in the middle of the night by Federalist marshal Jabez Fitch (the same "oppressive hand" Haswell had condemned) and immediately taken by horse to a jail in Rutland, some 50 miles away, to await adjudication.[3] In a trial conducted at Windsor on 5 May 1800 by Supreme Court Justice William Paterson he was found guilty of seditious libel, sentenced to a two-month imprisonment, and fined $200.[9]

The Haswell case has since been frequently mentioned in studies relating to freedom of the press, specifically with regard to the responsibilities of those who publish or repeat the words of others. It was cited by Justice Goldberg in his concurring opinion to the Supreme Court's New York Times Co. v. Sullivan decision. Haswell's release was heralded by the residents of Bennington who, it is said, had delayed the Fourth of July celebration several days so that it would coincide with Haswell's liberation.[10]

Subsequent life

Haswell's arrest occurred during a period of crisis for himself and his family. His first wife, Lydia, had died the year before, in April 1799, and Anthony had remarried in September to Betsy Rice, adopting her two children. However, the death of their mother, along with his legal and financial problems led to his daughters by Lydia having been adopted out, and three died during this period.[1][2][3]

In 1801, Haswell sent letters to Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, requesting government printing work. He reported that while his paper's circulation had once been 1400 per week, "[t]he unhappy political divisions which for some years past have afflicted our country, have been peculiarly injurious to me," and that he had been "reduced to distress, and almost to penury."[2][11] He indicated that, in spite of some community support, personal and family illness as well as the effects of his imprisonment left him unable to pay for new type, and he was considering abandoning printing in favor of becoming a farmer, although his concept of farming was more akin to that of the southern planter gentleman, envisioning long philosophical discussions while others supervised the farm work.[2][12] He did receive the government printing concession,[2] and continued as a printer for another decade and a half, briefly attempting another magazine as well as producing several books, notably Memoirs and Adventures of Captain Matthew Phelps.

Haswell took an interest in his community, allowing his son to be used as a test subject for smallpox vaccination in 1801.[2][13] He experienced a religious conversion in 1803, joining the Bennington church after 20 years as a non-participant.[14] In the same year, he became Clerk of the Vermont House of Representatives, serving for one year. He was also active in the Vermont Masonic movement. In April 1815, his wife Betsy died, never having recovered from the delivery of her youngest child just over a month before, and Anthony followed her the next year, dying 26 May 1816.[1][2][3] He and both his wives are buried in the cemetery of the Old First Church of Bennington.

Haswell's children included Nathan Baldwin Haswell, a noted Vermont Masonic leader, James Madison Haswell, a Baptist missionary to Burma,[14] and doctor and preacher Charles Salem Haswell of the California State Senate.[2]

References

- Farmerie (2001)

- Farmerie (2015)

- Spargo

- A published biography of a grandson reports that he served in the Siege of Boston, and at the Battle of White Plains (Jonathan Fairbanks and Clyde Edwin Tuck, Past and Present of Greene County Missouri, vol. 1 (1915), pp. 720–722) but at least the first seems unlikely on chronological grounds. Farmerie (2015)

- Duffy, et al., Ullery, et al.

- Duffy, et al.; Ullery, et al. Haswell also twice lost his Bennington homes to fire, one destroying the unsold copies of Allen's Reason and being viewed at the time as divine retribution.

- "Workshops & Classes".

- Wharton, Stone

- Stone. The fine, with interest, was returned to the Haswell family in 1844, by act of Congress. Farmerie (2015)

- Stone

- Brugger, vol. 1, p. 58

- Oberg, vol. 34, pp. 75–77, 601–2

- Jennings, 223

- Jennings

Bibliography

- Robert J. Brugger, et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison, Secretary of State Series, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, vol. 1, p. 58

- John J. Duffy, Samuel B. Hand, Ralph H. Orth, The Vermont Encyclopedia, UPNE, 2003, p. 153

- Todd A. Farmerie, "The Family of William Haswell, Father of Immigrant Anthony Haswell of Bennington, Vermont", New England Historical and Genealogical Register, vol. 155, pp. 341–352 (October 2001)

- Todd A. Farmerie, "Episodes in the Life of Anthony Haswell, Postmaster of the Vermont Republic", Vermont Genealogy, vol. 20, pp. 167–191 (July 2015)

- Isaac Jennings, Memorials of a Century, Boston: Gould and Lincoln, 1869, pp. 303–307

- Barbara B. Oberg, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Princeton: Princeton University Press, vol. 34, pp. 75–77, 601–601.

- John Spargo, Anthony Haswell: Printer — Patriot — Ballader: A Biographical Study with a Selection of his Ballads and an Annotated Bibliographical List of his Imprints. Rutland, VT: The Tuttle Co., 1925.

- Geoffrey R. Stone, Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism, W. W. Norton & Company, 2004, pp. 63–64.

- Jacob G. Ullery, Redfield Proctor, Charles H. Davenport, Hiram Augustus Huse, Levi Knight Fuller, Men of Vermont: An Illustrated Biographical History of Vermonters and Sons of Vermont, Brattleboro, Vt.:Transcript Publishing Company, 1894, p. 64

- Francis Wharton, State Trials of the United States during the Administrations of Washington and Adams, Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1849, pp. 684–687.