Antun Vrančić

Antun Vrančić or Antonio Veranzio (30 May 1504 – 15 June 1573;[2] Lat. Antonius Vrancius, Wrancius, Verantius iWerantius, It. Antonio Veranzio, Hung. Verancsics Antal[3]) was a Croatian[1] prelate, writer, diplomat and Archbishop of Esztergom in the 16th century. Antun Vrančić was from the Dalmatian town of Šibenik (modern Croatia), then part of the Republic of Venice.[4] Vrančić is also known under his Latinized name Antonius Verantius, while Hungarian documents since the 19th century[5] refer to him as Verancsics Antal.[6][7]

His Excellency Antun Vrančić | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Esztergom Primate of Hungary | |

Engraving of Vrančić by Martin Rota | |

| Archdiocese | Archdiocese of Esztergom |

| Installed | 17 October 1569 |

| Term ended | 15 June 1573 |

| Predecessor | Miklós Oláh |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 3 August 1554 |

| Created cardinal | 5 June 1573 by Pope Gregory XIII |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 30, 1504 |

| Died | June 15, 1573 (aged 69) Eperjes, Kingdom of Hungary (today Prešov, Slovakia) |

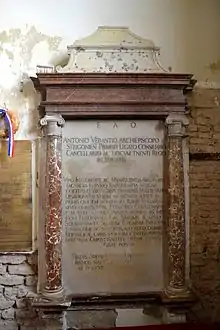

| Buried | Saint Nicolas' Church, Trnava (Slovakia) |

| Nationality | Venetian Croatian[1] |

| Occupation | Writer, diplomat and Archbishop of Esztergom |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Motto | "Ex alto omnia" |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church in Croatia |

|---|

|

Biography

Family origins

The Vrančić family name was originally recorded as Wranijchijch, Wranchijch and Veranchijch, later additionally latinized as Veranzio and Verancsics.[8][9]

According to one hypothesis it originates from Bosnia as one of the Bosnian noble families that had moved to Šibenik in the era of Ottoman military incursions of the 15th century,[10] or before due to some political events.[9] There the family was allegedly ennobled with lilies in coat of arms by Louis I of Hungary (noble status confirmed later only in the 16th century),[9] and following the Ottoman conquest of Bosnia, only certain Ivana Vrančić and his wife and children escaped.[11] However, Bosnia fell in 1463 and according to the family genealogy and Federico Antonio Galvani (1884), the Vrančić family members were citizens of Šibenik already from the 14th century, when is recorded Nicolo nicknamed Cimador (1360) who had a son Giovanni, mentioned in 1444 as member of the noble council, who in marriage with Agnesia Gambara of Venice had son Antonio (b. 1423) whose sons were Pietro (b. 1474) and Francesco (b. 1482-d. 1563).[9][12]

Antun Vrančić, in a letter to Hasan-beg Sancakbey of Hatvan in 1559, states that they both are born as Croats and shared Croatian ethnicity brings them closer together.[13][14][15] In his official talks with Rüstem Pasha, upon request of Pasha himself, spoke Croatian language because it was their mother tongue.[15][16][17]

Early years

Vrančić was born on 30 May 1504 (29 May is an erroneous date[2]), and raised in Šibenik, a city in Dalmatia in the former Republic of Venice.[4] His father was Francesco/Frane Vrančić (c. 1481/82-1563), paternal grandfather Antonio/Antun Vrančić (b. 1423) and great-grandfather Zuanne/Giovanni/Ivan Vrančić (mentioned 1444), while his mother was Marietta/Margareta Statileo/Statilić.[18] Antun had seven brothers and two sisters from his mother Margareta and stepmother Angelica/Anđelika Ferro, by letters was most closely connected to Michaele/Mihovil (1507/13-1570/71), Piero/Petar (1540-1570) and Giovanni/Ivan (1535-1558),[19][20] but also nephews Faust (1551-1617), Kazimir Vrančić (1557-1637), Jeronim Domicije-Berislavić (b. c. 1533) among others.[21]

Vrančić's uncle by mother side Ivan Statilić and his other relative, Croatian viceroy Petar Berislavić, took care of his education.[22][3] His maternal uncle, János Statileo, Bishop of Transylvania also supported him in Trogir, Šibenik, from 1514 in Hungary and in Padua, where he earned the degree of magister in 1526. After later studies at Vienna and Kraków, Vrančić entered diplomatic service, aged only 26.[4] Later in his life was guardian and took care of younger brother Jerolim and Ivan, and nephews Faust Vrančić and Jeronim Domicije education.[23]

Zápolya's service

In 1530 John Zápolya appointed him as the provost of the Buda cathedral and as a royal secretary. Between 1530 and 1539 he was also the deputy[24] of the King and after his death he remained with his widow, Isabella Jagiellon.[25] In 1541 he moved with her to Transylvania, but he mostly traveled fulfilling diplomatic services because of his disagreement with cardinal Juraj Utješinović's policy of claiming the Hungarian throne for Isabella's and Zápolya's infant son (instead of conceding it to Ferdinand I as per the Treaty of Nagyvárad). Utješinović, appointed by Zápolya as the guardian to his son, John Sigismund Zápolya, fought against Ferdinand and allied himself with the Ottoman Empire.

Habsburg service

In 1549 Vrančić entered Ferdinand's service. In parallel to his diplomatic duties, he held important positions in the Catholic Church (chief dean of Szabolcs County and abbot of Pornó Abbey). In 1553 he was appointed bishop of Pécs and sent to Constantinople to conduct negotiations with sultan Suleiman I on Ferdinand's behalf. That mission was previously declined by many other diplomats as an earlier negotiator was imprisoned by the Ottomans. Vrančić spent four years in Asia Minor and finally concluded a peace treaty. After his return he was appointed bishop of Eger (17 July 1560 – 25 September 1570). After the Battle of Szigetvár in 1566, as one of Maximilian's ambassadors, Vrančić was sent to Turkey to negotiate peace again; he arrived in Constantinople on 26 August 1567.[26] After five months of negotiations with Sokollu Mehmed Pasha and Selim II, agreement was reached by 17 February, and the Treaty of Adrianople was signed on 21 February 1568, ending the war between the Holy Roman Empire and Ottoman Empire.[26] In appreciation of his diplomatic work, the king named him archbishop of Esztergom (17 October 1569 – 15 June 1573).

During his stay in Istanbul, together with Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq, Vrančić discovered Res Gestae Divi Augusti (Eng. The Deeds of the Divine Augustus), a Roman monument in Ankara. His travels throughout Transylvania, the Balkans and Asia Minor resulted in his writing extensive travel accounts.

In 1573 he urged Maximilian II to be conciliatory toward the rebellious serfs during Croatian–Slovene Peasant Revolt. He remained very critical towards the Croatian magnates, stressing their responsibility in the revolt and claiming that the Croatian nobles oppress their serfs in ways equal to the Turkish yoke.[27] This attitude was in stark contrast with cardinal Juraj Drašković, ban of Croatia.

On 25 September 1573, he crowned Rudolf II king of Hungary and Croatia in Pressburg.

Death

He died in Eperjes, Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Prešov, Slovakia), just days after having learned that the Pope appointed him cardinal.[22] Following his own wish, Vrančić was buried in Saint Nicholas church in Nagyszombat, Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Trnava, Slovakia).[22]

Influences

Vrančić was in touch with German philosopher, theologian and reformer Philipp Melanchthon (1497–1560); and with Nikola Šubić Zrinski (1508–1566), Croatian ban, poet, statesman and soldier. In Viaggio in Dalmazia ("Journey to Dalmatia", 1774), Alberto Fortis noted that Vrančić's descendants still kept a letter to Vrančić from Dutch philosopher, humanist and writer Erasmus (1465–1536), but no other evidence of correspondence between the two exists today, and modern scholars find it unlikely.[28]

Legacy

After Vrančić's death, his nephew Faust, who was a well known humanist, linguist and lexicographer of the Renaissance, took over writings from his estate.[4] Two years later, in 1575, he wrote Life of Antun Vrančić, a biography of his uncle, but did not manage to have it published.[29]

Croatian poet Brne Karnarutić dedicated his version of Pyramus and Thisbe to Vrančić in 1586. Antun Vrančić High School in Vrančić's native Šibenik has been named after him since 1991, while a street in the old town centre also bears his name. Many other towns in Croatia have a street named after Vrančić. Croatian Post issued a stamp depicting Vrančić in 2004 honoring the 500th anniversary of his birth.[30]

Bibliography

- De situ Transylvaniae, Moldaviae et Transalpinae

- Vita Petri Berislavi

- De rebus gestis Ioannis, regis Hungariae

- De itinere et legatione sua Constantinopolitana cum fratre Michaele dialogus

- Iter Buda Hadrianopolium

References

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The Sixteenth Century. Vol. IV. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. p. 921. ISBN 0-87169-162-0.

- Sorić 2015, p. 37.

- Blažević & Vlašić 2018, p. 28.

- Cvitan, Grozdana (May 19, 2005). "Kako sam služio ugarskog kralja". Zarez (in Croatian) (132). Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- László Szalay, Gusztáv Wenzel: Magyar történelmi emlékek, Verancsics Antal összes munkái, 1858 (The Works of Antal Verancsics)

- Google Books Andrew L. Simon: Made in Hungary: Hungarian contributions to universal culture

- The Hungarian Quarterly, Vol. XLII * No. 162 *, Summer 2001 Archived 2011-07-12 at the Wayback Machine László Sipka: Innovators and Innovations

- Verancsics (Vrančić), Antal (Antun) (1860). Monumenta Hungariae historica. Magyar törtenelmi emlekek ... (in Latin). Pest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia. pp. 360–372.

- Galvani, Federico Antonio (1884). Il re d'armi di Sebenico con illustrazioni storiche (in Latin). Venezia (Venice): Prem. stabil. tip. di Pietro Naratovich. pp. 215–223.

- Morić, Živana (June 12, 2004). "Europski obzori hrvatskoga humanista" (PDF). Vjesnik (in Croatian). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2007. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- Podhradczky, József (1857). Néhai Werancsics Antal esztergami érseknek példás élete (in Hungarian). Pest. pp. 11–12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sorić 2014, p. 38.

- "Monumenta Hungariae historica" 2. osztály, Irók, Volumes 19-20 (in Latin). Pest: Magyar tudományos akadémia történelmi bizottmány. 1868. pp. 77–78.

maxime ob propinquitatem nostrae nationis Croatae, unde et nos natos ... cuius non modo Croatici generis propinquitas ... pro ea vicinitate, et nostrae gentis Croaticae propinquitate, quae nobis ambobus grata est, velit remissius

- Veljko Gortan, Vladimir Vratović, ed. (1969). Hrvatski latinisti (in Croatian). Vol. I. Zagreb: Matica hrvatska. p. 636, 638.

- Tunjić, Andrija (21 November 2019). "Mario Grčević - Hrvatski studiji postat će fakultet već ove akademske godine". Vijenac (in Croatian). Zagreb: Matica hrvatska. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Sorić 2009, p. 91.

- Blažević & Vlašić 2018, pp. 42–87.

- Sorić 2014, pp. 37–38, 41, 43.

- Lončar & Sorić 2013, p. 1.

- Sorić 2014, pp. 36–39.

- Sorić 2014, pp. 36, 41–42.

- "Na današnji dan: Umro Antun Vrančić" (in Croatian). Croatian Radiotelevision. June 15, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- Sorić 2014, pp. 44–45.

- "Verancsics – Magyar Katolikus Lexikon". lexikon.katolikus.hu.

- http://www.biolex.ios-regensburg.de/BioLexViewview.php?ID=1861 here

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571: The Sixteenth Century. Vol. IV. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. pp. 921–922. ISBN 0-87169-162-0.

- Bogo Grafenauer, Boj za staro pravdo na Slovenskem (Ljubljana, 1973), 147-48.

- Lučin 2004, pp. 11–12.

- Lisac, Josip (December 22, 2001). "Svestranik iz Šibenika" (PDF). Vjesnik (in Croatian). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2004. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- "Postage stamp overview: FAMOUS CROATS, Faust Vrančić". posta.hr. Croatian Post. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

Sources

- Stoy, Manfred (1981). "Vrančić, Antun". Biographisches Lexikon zur Geschichte Südosteuropas (in German). Vol. 4. Munich: R. Oldenbourg. pp. 442–444 – via Leibniz Institute for East and Southeast European Studies.

- Lučin, Branislav (December 2004). "Erazmo i Hrvati XV. i XVI. stoljeća" [Erasmus and Croats in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries] (PDF). Prilozi za istraživanje hrvatske filozofske baštine (in Croatian). Zagreb: Institute of Philosophy. 30 (1–2 (59–60)): 5–29. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- Sorić, Diana (2009). "Klasifikacija pisama Antuna Vrančića". Colloquia Maruliana (in Croatian). 18 (18).

- Lončar, Milenko; Sorić, Diana (2013). "Using Script Against Undesirable Readers: The Coded Messages of Mihovil and Antun Vrančić". Sic. 4 (1).

- Sorić, Diana (2014). "Obiteljski korespondenti Antuna Vrančića (1504.-1573.): Biografski podaci i lokacija rukopisne građe". Povijesni Prilozi. 33 (47): 35–62.

- Sorić, Diana (2015). "The question of the birth date of Croatian humanist and Hungarian primas Antun Vrančić (1504 – 1573)". Croatica Christiana periodica. 39 (75): 37–48.

- Blažević, Zrinka; Vlašić, Anđelko, eds. (2018). Carigradska pisma Antuna Vrančića: Hrvatski i engleski prijevod odabranih latinskih pisama [The Istanbul Letters of Antun Vrančić: Croatian and English Translation of Selected Latin Letters] (PDF) (in Croatian and English). Zagreb, Istanbul: HAZU. ISBN 978-9752439061.