Anomocephalus

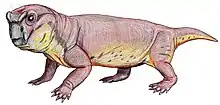

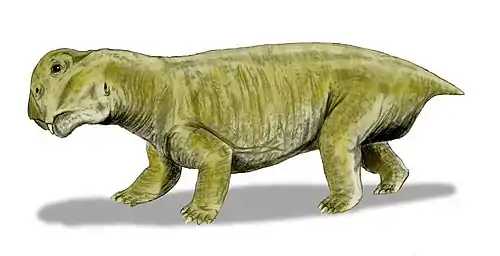

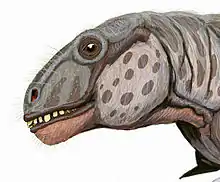

Anomocephalus is an extinct genus of primitive anomodonts and belongs to the clade Anomocephaloidea. The name is said to be derived from the Greek word anomos meaning lawless and cephalos meaning head.[1] The proper word for head in Greek is however κεφαλή (kephalē).[2] It is primitive in that it retains a complete set of teeth in both jaws, in contrast to its descendants, the dicynodonts, whose dentition is reduced to only a single pair of tusks (and in many cases no teeth at all), with their jaws covered by a horny beak similar to that of a modern tortoise. However, they are in no way closely related.

| Anomocephalus Temporal range: Middle Permian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Anomodontia |

| Clade: | †Anomocephaloidea |

| Genus: | †Anomocephalus Modesto et al., 1999 |

| Species: | †A. africanus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Anomocephalus africanus Modesto et al., 1999 | |

Its discovery in 1999 from the earliest terrestrial rocks of Gondwana (from Williston in the Karoo of the Northern Cape Province of South Africa) has shown that this group of herbivores originated in Gondwana; not Laurasia, as had previously been supposed. It lived 260 million years ago during the Permian Period, in arid areas with rivers and lakes - almost like parts of modern-day Namibia or Botswana.[1] It is most closely related to Tiarajudens from Brazil.[3]

Geology and paleoenvironment

Anomocephalus was discovered at the base of the Beaufort Group, which is a geographical stratum that consists of mostly sandstone and shales that have been deposited in the Karoo Basin.[1][4] The Beaufort Group dominated most of the basin with fluvial sedimentation, which is carried by streams and rivers that were most likely formed by ice masses such as glaciers.[5] The climate at this time during the Mid to Late Permian became warm and semi-arid with seasonal rainfall.[5] The central region of the basin is thought to have been drained by semi-permanent lakes and fine-grained meander belts.[5]

History and discovery

Anomocephalus was collected from a locality near Williston at the base of the Beaufort Group in the Karoo Basin, which is located within the Northern Cape Province of South Africa.[1] It was discovered during the continued program of B. Rubidge to determine the lateral extent of the Eodicynodon (an extinct dicynodont therapsid) Assemblage Zone.[1] It was first described by Modesto in 1999 and is known only by a partial skull with distinctive dentition and was preserved in hard mud rock.[1]

The discovery of Anomocephalus and its phylogenetic position provided compelling evidence that anomodonts initially diversified in Gondwana.[1] This conflicts with previous suggestions that anomodonts were freely dispersing between the northern and southern regions of the Late Permian Pangea or that therapsids first evolved in Euramerica and then moved to Gondwana when climate became favorable.[1][6][7] Additionally, the basal phylogenetic position of Anomocephalus suggests that herbivory was acquired initially by the anomodonts of Gondwana.[1]

Description

Skull

The premaxilla contains a deep alveolar portion with room for two teeth and the maxilla is slightly elongated in comparison to other anomodonts.[8][1] On the posterior portion of the maxilla, the characteristic anomodont curvature is seen in the zygomatic arch.[8][1] The nasal, prefrontal, and lacrimal resemble in both form and position those of other more basal anomodonts.[1] Additionally, the jugal has a greater marginal exposure than other anomodonts and it tapers posteriorly.[1] The dorsal lamella of the quadratojugal more closely resembles dicynodonts than basal anomodonts.[1] The postorbital bone tapers ventrally and is visibly flat and curved.[1] Like in other anomodonts, the dentary is dorsoventrally deep, and the squamosal is triradiate as suggested by the ventral and anterior processes.[8][1]

Dentition

Anomocephalus possess five upper incisors that have an ovoid-shaped crown when observed from the occlusal view.[9] The dentition of the maxilla begins as tiny peg-like elements that become buccolingually wide and mesiodistally short.[9] Six teeth are located on the pterygoid/ epipterygoid with four additional empty/damaged alveoli which suggests that there were at least ten teeth that made up the right palatal dentition.[9] These palatal teeth have long, curved roots and the crowns are rectangular with an occlusal basin.[9] There are two in situ lower incisiforms that are followed by two displaced lower teeth, the second of these teeth is transversally expanded and shows a saddle-like crown just like the palatal teeth.[1][9] Additionally, there are three posterior lower teeth on the dentary with an unerupted, replacement tooth evident below the last lower tooth, which is evidence of at least a second wave of tooth replacement.[9]

Post-cranial skeleton

Although a post-cranial skeleton was not found with the partial skull of Anomocephalus, its sister taxa Tiarajudens eccentricus was discovered in 2011 with a partial left pectoral girdle and its left limb, an isolated left tibia with the pes, and foot elements.[9][3] Of the axial elements, only two fragmentary ribs of parallel margin were found with no clear curvature and the most complete fragment was 8 mm wide and 86 mm long.[9] The humerus that was found with T. eccentricus is approximately 177 mm in length and displayed well-expanded proximal and distal portions.[9] The radius is 128 mm in length with expanded, flat proximal and distal surfaces, and the ulna is more robust than the radius and slightly longer at 137 mm.[9] The pes showed five partial digits and they were all robust with arthrodial joints between the distal metatarsals and proximal phalanges as well as between the phalanges.[9] Additionally, 15 left and three right gastralia were preserved as long, thin, and delicate bones.[9]

Paleobiology

Anomocephalus exhibits palatal teeth and the morphology of the teeth is consistent with a high-fiber herbivorous diet.[9] Cisneros and colleagues suggested that Anomocephalus had an incipient propaliny during the occlusions due to the longitudinal dimensions of each facet of the quadrate being twice as large as the transversal dimension.[9][1] They suggest that this would allow for forward and backward movement of the lower jaw during chewing.[9] Propaliny is also suggested to be linked to improved capability for processing plant material.[10][11][12]

See also

References

- Modesto, S.; Rubidge, B.; Welman, J. (1999). "The most basal anomodont therapsid and the primacy of Gondwana in the evolution of the anomodonts". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 266 (1417): 331–337. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0642. PMC 1689688.

- Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Cisneros, J.C.; Abdala, F.; Rubidge, B.S.; Dentzien-Dias, D.; Bueno, A.O. (2011). "Dental Occlusion in a 260-Million-Year-Old Therapsid with Saber Canines from the Permian of Brazil". Science. 331 (6024): 1603–1605. Bibcode:2011Sci...331.1603C. doi:10.1126/science.1200305. PMID 21436452. S2CID 8178585.

- Hamilton (1928). "Outline of Geology for South African Students". Central News Agency LTD, Johannesburg.

- Smith, R. M. H. (1990). "A review of stratigraphy and sedimentary environments of the Karoo Basin of South Africa". Journal of African Earth Sciences (and the Middle East). 10 (1–2): 117–137. Bibcode:1990JAfES..10..117S. doi:10.1016/0899-5362(90)90050-o.

- Rubidge, B. S., B. S.; Hopson, J.A. (1990). "A new anomodont therapsid from South Africa and its bearing on the ancestry of Dicynodontia". S. Afr. J. Sci. 86: 43–45.

- Boonstra, L.D. (1971). "The early therapsids". Ann. S. Afr. Mus. 59: 17–46.

- Rubidge, B; Modesto, Sean (2000). "A basal anomodont therapsid from the lower Beaufort Group, Upper Permian of South Africa". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (3): 515–521. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0515:ABATFT]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 131397425.

- Cisneros, J.C.; Abdala, F; Dentzien-Dias, P; De Oliveira Bueno, A. (2015). "Tiarajudens eccentricus and Anomocephalus africanus, two bizarre anomodonts (Synapsida, Therapsida) with dental occlusion from the Permian of Gondwana". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (7): 150090. Bibcode:2015RSOS....250090C. doi:10.1098/rsos.150090. PMC 4632579. PMID 26587266.

- Reisz, R. R. (2006). "Origin of dental occlusion in tetrapods: signal for terrestrial vertebrate evolution?". J. Exp. Zoolog. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 306B (3): 261–277. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21115. PMID 16683226.

- Angielczyk, KD (2004). "Phylogenetic evidence for and implications of a dual origin of propaliny in anomodont therapsids (Synapsida)". Paleobiology. 30 (2): 268–296. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0268:pefaio>2.0.co;2. S2CID 86147610.

- King, DM (1990). "The dicynodonts: a study in palaeobiology". London, UK: Chapman and Hall.