Annery kiln

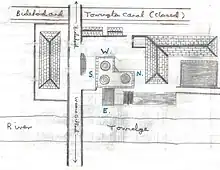

Annery kiln is a former limekiln of the estate of Annery, in the parish of Monkleigh, North Devon. It is situated on the left bank of the River Torridge near Half-Penny Bridge, built in 1835,[2] which connects the parishes of Monkleigh and Weare Giffard. Running by it today is A386 road from Bideford to Great Torrington. Weare Giffard is the start of the tidal section of the River Torridge, and thus the kiln was sited here to import by river raw materials for the kiln, the product of which was lime fertiliser for use on inland agricultural fields. The old lime kiln is thus situated between the River Torridge and the now filled-in Rolle Canal built circa 1827[3] and railway that ran formerly from Bideford to Torrington, opened in 1872 and closed in 1966.[4] The old trackbed now forms a stretch of the Tarka Trail.

History

Weare Giffard is situated near the tidal limit of the River Torridge, and coal and limestone had been brought up-stream by boat for a long time previously to the building of the Rolle Canal in 1823 - 1827.[5] Due to the corrosive properties of quick lime, the product of the kiln, it was essential that kilns should be situated as closely as possible to the agricultural fields on which it was to be spread. Should the quick lime become wet during transport by the farmer to his farm, it would corrode its container and damage the wagon or pack-animal on which it was being transported. Culm, a form of imperfect anthracite, was mined in Devon at Tavistock and Chittlehampton as well as being imported from South Wales via Bideford.[1] The limestone largely came from Caldey Island off the South Wales coast,[6] although Devon had quarries at Landkey, Swimbridge, Filleigh, South Molton and Combe Martin.[1]

The lime kiln complex comprised the kiln itself, a pond for slaking the calcium oxide from the kiln to produce the slaked lime, hydrated lime, or pickling lime. Several cottages were built nearby for the lime-burners, shipbuilders and blacksmiths, etc. and storage buildings. The main set of cottages are neither evidenced on any maps nor in census returns until after 1851, indicating that they were not built until later and only one census return in the 19th century lists a lime-kiln worker. A small wharf on the river allowed for the unloading of sailing barges.

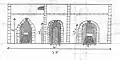

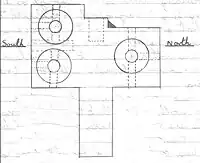

Annery limekiln has a ramp facing the river, three kilns (or burning 'pots'), seven entrance doorways and nine lower apertures for the removal of the calcined limestone. The arrangement of the kilns gives an L-shaped compact structure. Some of the entrances led to arched lobbies or 'eyes', at the back of which were the grates and separate 'poking holes' to insert metals rods for 'working' the charge and helping with aeration. A 'lean-to' slated roof may have slotted beneath part of the drip course of projecting stones, which runs around the exterior walls of the kiln. The arched entrances to the kiln allowed for the sheltered and safe collection of the quicklime, which reacted violently to water.

The top of the kilns was flat and large enough to allow for some storage of culm and limestone. Like Lord Rolle's kilns at Rosemore, Great Torrington and his nearby Town Mills they were at a late date crenellated with castle-like battlements,[7] an eccentric decorative feature probably added by John Rolle, 1st Baron Rolle (d.1842), of Stevenstone, lord of the manor of Great Torrington, builder of the Rolle Canal and partner in the building of Half-Penny Bridge with Mr Tardrew of Annery. Town Mills were crenellated to form an "eye-catcher" when viewed up the picturesque Torridge valley from Castle Hill, Great Torrington, which Lord Rolle had also castellated to recall the ancient castle. The original Annery kiln had been built prior to Lord Rolles's canal and the Great Torrington lime kilns; it is unlikely to have had the crenellations.

Annery was well built, with local mortar-cemented stones, a rubble infill and firebricks lining the kilns' combustion chambers.[1] The various openings to the kilns have rounded or pointed Gothic arches formed from bricks. The now lost crenellated 'battlements' construction was similar to other kilns such as those at Yeo Vale on the Torridge, south-west of Bideford and those at Torrington.[8]

Evidence suggests that the original kiln had a single pot and arched entrances leading to three 'eyes', and that later two more pots were built with rounded tops to the arches which led to only two eyes each.[7] The decorative front of the new kiln has blind arches at either end and two quatrefoils, symmetrical shapes which form the overall outline of four partially overlapping circles of the same diameter.

The kiln had excellent communications, originally being sited simply next to the river, but gaining later the additions of the canal, the road between Bideford and Torrington, as well as the new Half-Penny toll-bridge across the Torridge to Weare Giffard, built in 1835 by Lord Rolle and Mr Tardrew.[2] In Devon the demand for agricultural lime in the 19th century was very high, and farmers from a wide area collected loads of lime from Annery, by pack-horse at first and later using wagons,[9] They arrived sometimes as early as 4am to ensure a supply for the day.[1]

The development of the rail network made local small-scale kilns generally unprofitable, but Annery had closed in around 1864, before the local railway was opened. Local competition from the lime kilns at Torrington and elsewhere would have been intense.[1]

Annery Kiln in 1971

The limekiln from the main road and old railway.

The limekiln from the main road and old railway. A view from the river side.

A view from the river side. The fueling opening into which the limestone and coal were tipped.

The fueling opening into which the limestone and coal were tipped. The ramp leading up to the fueling points.

The ramp leading up to the fueling points.

Limekiln drawings gallery

Drawings produced in 1971. The measurements are only approximate.

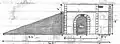

Internal structure of the kiln.

Internal structure of the kiln. The West facing elevation.

The West facing elevation. The East facing elevation.

The East facing elevation. North - East facing elevation.

North - East facing elevation.

Limekilns

Function

Annery had three burning chambers constructed of brick, each with an air inlet (the "eye") at the base. Crushed limestone and coal unloaded from a boat on the nearby tidal River Torridge or possibly the Rolle Canal, were hauled up the single ramp and emptied into the kiln chamber. Successive dome-shaped layers of culm coal and limestone would have been built up in the kiln on grate bars across the eye at the base. When loading or 'charging' was completed, the kiln would have been kindled at the bottom, and the fire gradually allowed to spread upwards through the charge. When burnt through, the lime was cooled and raked out through the base.

The size of kilns was limited by the need to allow air to permeate freely and to prevent a collapse from too much weight; this explains why individual kilns were all much the same size and therefore multiple kilns— three at Annery— were necessary to increase production. Each kiln usually made between 25 and 30 tonnes of lime in a batch; at Annery they may have been fired in rotation to ensure a continuous supply.

Typically each kiln took around a day to load, three days to fire, two days to cool and a day to unload. The degree of burning was controlled by trial and error from batch to batch by varying the amount of fuel used. There were large temperature differences between the center of a charge and the material close to the wall, so a mixture of under-burned, well-burned and dead-burned lime was normally produced. Typical fuel efficiency was low and the job was labour-intensive, with a loading gang and an unloading gang who would work the kilns in rotation through the week. The heat was intense and the smoke considerable, making this a very dangerous occupation.

Lime and its uses

Lime kilns are used to produce Calcium oxide or quicklime by calcinating limestone. The reaction involved takes place at around 900 °C, but a temperature around 1000 °C is usually used to make the reaction proceed more quickly.[11] Excessive temperature is avoided because it produces unreactive or "dead-burned" lime.

Lime is used in building as a mortars and also as a stabilizer in mud renders and floors.[12] Lime is much used in agriculture, but it only became widely possible when the use of coal made it cheaper.[13]

Land transportation of bulky minerals like limestone and coal was difficult in the pre-industrial era due to the poor condition of the roads, so they were distributed by sea; the lime most often being manufactured at small coastal ports and then taken inland by carts. Many of the surviving kilns are still to be seen on quaysides around the coastline of the United Kingdom.

History of Annery and Weare Giffard

Rolle Canal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Annery is a nearby former historic estate. Old maps show that a country house of that name existed there in the 18th century. Another lime kiln existed opposite Weare Giffard and the name was either used to distinguish the two or Annery may have been the manorial kiln which supplied the tenants.

During a visit to Annery Kiln in 1971 one of the old cottages had a chimney fire. The householder sorted the problem out by firing both barrels of a 12 bore shotgun up the offending chimney, extinguishing the fire whilst at the same time 'cleaning the chimney!'[1]

In the 1970s the kiln was used as a garage and store (see photographs) and was a community in its own right, known as Annery Kiln.

The small shipyard that had existed at Annery was moved down to the sea lock when the canal was built.[14]

William Tardrew of Annery was a share holder in the Rolle Canal Company and held lands along the length of the canal.[14]

Adjacent to the Annery kiln is Brick Marsh, which was the site of the Devon or Annery Pottery.[14]

The name of the village is variously written as Weare 'Giffard' or 'Gifford,' the former being more frequently used. The Giffard family are recorded as having been in the area since at least the year 1219.[15] Annery was first recorded as 'Auri' in 1193.[16]

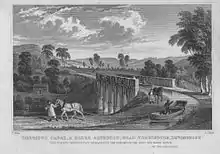

The Beam Aqueduct (see illustration) has long been used as a road bridge to a private house and below it were filmed several pivotal scenes for the Tarka the Otter film.

References and Bibliography

- Griffith, R. S. Ll. (1971). Annery Kiln, Weare Giffard. Grenville College project. Supervisor Mr. B. D. Hughes.

- Scrutton, Sue, Lord Rolle's Canal, Great Torrington, 2006, p. 23.

- Minchinton, Walter (1974), Devon at work: Past and Present. Pub. David & Charles; Newton Abbot. ISBN 0-7153-6389-1. P. 82.

- Mitchell, V. & Smith, K. (1994) Branch Lines to Torrington Pub. Middleton Press, ISBN 1-873793-37-5.

- Hadfield, Charles (1967), The Canals of South West England. Pub. David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

- Hadfield, Charles (1967), The Canals of South West England. Pub. David & Charles, Newton Abbot. p. 137.

- the History of Weare Giffard.

- Minchinton, Walter (1974), Devon at work: Past and Present. Pub. David & Charles; Newton Abbot. ISBN 0-7153-6389-1. P. 38.

- Hadfield, Charles (1967), The Canals of South West England. Pub. David & Charles, Newton Abbot. P. 135.

- Stoddart, John (1800), Remarks on Local Scenery and Manners in Scotland. Pub. Wiliam Miller, London. Facing p. 212.

- Parkes, G.D. and Mellor, J.W. (1939). Mellor's Modern Inorganic Chemistry London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Hewlett, P. C. (Ed), (1998). Lea's Chemistry of Cement and Concrete: 4th Ed, Arnold, ISBN 0-340-56589-6, Chapter 1

- Platt, Colin (1978). Medieval England, BCA, ISBN 0-7100-8815-9, pp 116-7

- The Rolle Canal. Rolle Canal and Northern Devon Waterways Society website Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Gover, J. E. B., Mawer, A. and Stenton, F. M. (1931). The Place-Names of Devon. Part 1, Pub. Cambridge University Press. p. 111.

- Gover, J. E. B., Mawer, A. and Stenton, F. M. (1931). The Place-Names of Devon. Part 1, Pub. Cambridge University press. P. 101.