Anne of Denmark and contrary winds

Anne of Denmark (1574–1619) was the wife of King James VI and I, and as such Queen of Scotland from their marriage by proxy on 20 August 1589 and Queen of England and Ireland from 24 March 1603 until her death in 1619. When Anne intended to sail to Scotland in 1589 her ship was delayed by adverse weather. Contemporary superstition blamed the delays to her voyage and other misfortunes on "contrary winds" summoned by witchcraft. There were witchcraft trials in Denmark and in Scotland. The King's kinsman, Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell came into suspicion. The Chancellor of Scotland John Maitland of Thirlestane, thought to be Bothwell's enemy, was lampooned in a poem Rob Stene's Dream,[1] and Anne of Denmark made Maitland her enemy.[2] Historians continue to investigate these events.[3][4]

The historian Liv Helene Willumsen, who examined international correspondence and highlighted examples of the phrase "contrary winds", said that in 1589 fears over straightforward events like adverse weather at sea were blamed on supernatural causes, and the powerless and the vulnerable, to bolster personal and royal honour.[5]

Sailing from Copenhagen

Anne of Denmark sailed on 5 September 1589 with Peder Munk and Henrik Knudsen Gyldenstierne, admiral of the fleet, and 18 ships.[6] The Danish fleet included the Gideon, Josaphad or Josafat their flagship, Samson, Joshua, Dragon, Raphael, St Michael, Gabriel, Little Sertoun (Lille Fortuna), Mouse, Rose, the Falcon of Birren, the Blue Lion, the Blue Dove (Blaa Due) and the White Dove (Hvide Due).[7] When they were only a mile away from the palace of Kronborg, adverse winds prevented progress for two days.[8]

Anne's fleet sailed west but the wind failed them and they put in to Flekkerøy, an island on the coast of Norway, where Peder Munk was able to arrange a welcoming banquet. Contrary winds frustated attempts to progress from Flekkerøy.[9] The Gideon began to leak, and Peder Munk told Anne that the hold was filling with water despite the prayers of the learned academics and diplomats Paul Knibbe and Niels Krag. Two ships, the Parrot and the Fighting Cock were scattered from the fleet.[10] Peder Munk and the Danish nobles discussed their options to return to Denmark or go to Oslo with the Scottish representative, George Keith, 5th Earl Marischal.[11]

Lord Dingwall's ship arrived at Stonehaven with the news of the storm and the apprehension that the Queen was in danger on the seas.[12] James VI wrote to the Earl Marischal, Anne's companion, (who he called "My little fat pork"), on 28 September asking for news, and worried about the "longer protracting of time" and the "contrariousness of winds".[13]

While waiting for his bride at Seton Palace and Craigmillar Castle, James VI may have begun a series of love poems in Scots now known as the Amatoria.[14] A manuscript copy of the eleven Amatoria sonnets in the British Library gives the first poem the title, "A complaint against the contrary Wyndes that hindered the Queene to com to Scotland from Denmarke", although internal evidence suggests the poems were completed later.[15]

James VI decides to sail to Norway

King James decided to go to Norway himself after he received letters from Anne of Denmark saying she had been delayed from setting out and would not try again.[16] The diplomats Steen Bille and Andrew Sinclair had brought the letters to King James on 10 October.[17] Anne of Denmark had written two letters from Flekkerøy near Oslo in Norway, in the French she had learned in preparation for her marriage.[18] She signed one letter as "Anne" and another as "Anna". The "Anna" letter includes this phrase, about vents contraires;[19]

"nous sommes desja par quatre ou cinq fois avances en la mer, mais que par vents contraires et autres inconvenients y survenus, avons maintenant nous present, et la redoubtance de plus grands dangers qui sont tresapparents a contrainct toute ceste compagnie, bien à nostre grand regret et des vostres, qui en sont extrement desplaisants, de prendre une resolution, de ne rien plus attenter pour ceste fois, ains de differer le voiage jusques à la primevere"

we have already put out to sea four or five times but have always been driven back to the harbours from which we had sailed, thanks to contrary winds and other problems which arose at sea, which is the cause why, now Winter is hastening down on us, and fearing greater dangers which are clearly apparent, all this company is forced, much to our regret, and that of your men, who are highly displeased about it, to make a decision to make no further attempt at this time, but to defer the voyage until the spring.[20]

Anne's mother Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow and her brother Christian IV sent similar letters.[21] James VI made his decision at Craigmillar Castle.[22] The Chancellor of Scotland, John Maitland of Thirlestane, who had previously advocated that the King marry a French Protestant bride, Catherine de Bourbon, now backed the Danish marriage.[23]

To Norway and Denmark

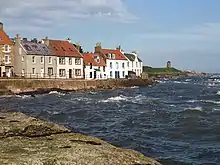

On account of the "sundrie contrarious windis" that delayed the Danish fleet, on 11 October James VI asked East coast mariners and ship masters to come to Leith.[24] James VI sailed with six ships hired from owners including Robert Jameson.[25] Patrick Vans of Barnbarroch hired the Falcon of Leith from John Gibson.[26]

King James took as chaplains John Scrimgeour, minister of Kinghorn, a parish beside the sea in Fife,[27] and David Lindsay, minister of Leith.[28] The king's sailing was delayed by a storm until the evening of 22 October. Finally, he embarked and sailed to Flekkerøy, encountering a storm on the way.[29] He landed on 3 November and slept in the same farmhouse on the island as Anne had.[30] Steen Bille set off to bring the new of his arrival to Copenhagen, and there was a tragic accident. When cannons were fired to salute his departure a young sailor was maimed or killed.[31] The merchant William Hunter wrote:

"Thair was a boy off our schip that was schot with a pece of ordenance owt off the Kingis schip - at the departour of Stean Belde - be neglegence off the gwner, quho thoght thair had bene no schott in hir. This schip is send back agane with suche personis in hir as ar nocht fwnd meit to ramane heir"

(modernised) There was a boy of our ship that was shot with a piece of ordnance out off the King's ship - at the departure of Steen Bille, by negligence of the gunner, who thought there had been no shot in her. This ship is sent back again [to Scotland] with such persons in her as are not found meet to remain here.[32]

James VI took three weeks to get to Oslo, journeying slowly in the "mikle foull wather of a stormie winter".[33] After stopping at Tønsberg, he met his queen at Oslo, and married her at the Old Bishop's Palace in Oslo on 23 November 1589, the residence of the Mayor, Christen Mule. He wore red and blue outfits embroidered with gold stars.[34] In Edinburgh, the English ambassador William Asheby wrote of political agitators as enchanters raising tempests, deserving their own shipwreck.[35]

Following the wedding, the party stayed in Oslo for a while, and on 15 December the Danish nobles Steen Brahe and Steen Bille sailed for Denmark.[36] Before they left, James VI gave them and Axel Gyldenstierne gifts of silver plate.[37] Colonel William Stewart sailed back to Edinburgh with instructions for the royal homecoming in the spring, and news of arguments between Chancellor Maitland and the George Keith, 5th Earl Marischal and his kinsman William Keith of Delny, over precedence and the Queen's dowry.[38]

After some correspondence with his mother-in-law, Sophie of Mecklenburg, the Scottish royal party travelled to Varberg and crossed from Helsingborg to Elsinore, or Helsingør, in Denmark to join the Danish royal court.[39] James made "gude cheir and drank stoutlie till the springtyme".[40] The King played cards and a dice game called "mumchance" to pass the time. Andrew Sinclair organised the building of a new ship for the King's fleet.[41]

Voyage to Scotland

At Kronborg in April, aware of the usual uncertainties of weather at sea, James VI wrote "in deadest calms ye know sudden and perilous puffs and whirlwinds will arise".[42] The couple attended the marriage of Elisabeth of Denmark and Henry Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg on 19 April. Additional ships, including the Angel of Kirkcaldy were hired in Scotland for the return voyage.[43] They sailed back to Scotland on 21 April, arriving on 1 May.[44] There had been rumours that an English fleet of 10 ships had been seen off North Berwick, intending to intercept the Scottish royals. The English ambassador Robert Bowes was anxious to quash these rumours which threatened the amity between England and Scotland, and he stopped the Privy Council of Scotland sending a fast pinnace to warn the king of this false rumour.[45]

Jane Kennedy and the loss of the Forth ferry boat

Jane Kennedy and her servant Susannah Kirkcaldy were drowned on the 7 or 8 September 1589 crossing the Forth between Burntisland and Leith. The ferry boat was "midway under sail, and the tempest growing great carried the boat with such force upon a ship which was under sail as the boat sank presently." Jane Kennedy had been summoned from her home at Garvock near Dunfermline by James VI to await the arrival of Anne of Denmark, who was then expected to arrive at Leith.[46]

The ferry boat sank after colliding with another vessel during the storm, and the sailors of the other boat, William Downie, Robert Linkhope (or Luikhope), and John Watson of Leith were put on trial for the deaths of sixty passengers in January 1590. The outcome of the trial is not recorded.[47] The loss of the ferry boat in stormy weather with all but two of the passengers was subsequently blamed on witchcraft.[48][49] In the following year people from North Berwick were made to confess to raising the storms. In later years the disaster came to be blamed on an error of the sailors, said to be drunk in calm weather by a writer in 1636, who added that £10,000 of goods and jewels were lost.[50] Other records attest to the stormy weather of 1589, which destroyed cultivated rabbit warrens at the west links of Dunbar which supplied the royal household.[51]

Witch trials at North Berwick and the Danish connection

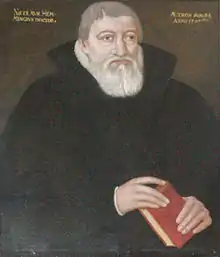

During the marriage trip, James VI met the Danish theologian Niels Hemmingsen at Roskilde on 11 March 1590 and they had a long discussion or debate in Latin. James VI, who had owned four of his books since 1575,[52] gave him a silver gilt cup. The English ambassador in Scotland, Robert Bowes heard they disagreed about predestination.[53] There is no record that their discussion involved the topic of witchcraft, a topic that Hemmingsen had published on.

In July 1590 the Scottish churchman and diplomat George Young, who had been with the King in Denmark, became involved in the case of a woman from Lübeck because he could speak German. She said she brought a prophecy from magicians of the east, of a great king in north-west Europe and his noble future actions, a "prince in the north" meaning James VI.[54] The king in the prophecy had a wound or mark on the side of his body. The woman had a letter written in Latin saying she brought news of the king's good fortune. She had tried to meet James VI at Elsinore but missed seeing him there. In Edinburgh, she had an audience with Anne of Denmark, speaking in German. James VI thought she was probably a witch, but asked Young to interview her.[55] At first she was reluctant to speak to him, preferring to talk to a "wise man" of her own choice and see the mark on the king's body first. The English diplomat Robert Bowes heard that she had come to Scotland because of her "inordinate love" for one of the queen's servants, and so her story of a prophecy was disregarded and her "credit cracked". This probably means she was questioned by Young to see if she was a false prophet or witch, and he found her to be deranged by her love.[56]

The North Berwick witch trials in 1590 involved a number of people from East Lothian, Scotland. They ran for two years, and implicated over seventy people. These included Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell.[57] The "witches" were alleged to have held their covens on the Auld Kirk Green, part of the modern-day North Berwick Harbour area. The confessions were extracted by torture in the Old Tolbooth, Edinburgh. One source for this story was published in a 1591 pamphlet Newes from Scotland and was subsequently published in King James's dissertation on contemporary necromancy titled Daemonologie in 1597.

The North Berwick trials were one of the first major witchcraft persecutions in Scotland, and began with this sensational case involving the royal houses of Denmark-Norway and Scotland. King James VI had sailed to Norway to meet his bride Anne of Denmark, sister of Christian IV of Denmark. During their return to Scotland they experienced terrible storms and had to shelter in Norway for several weeks before continuing. At this point, the interest in witch trials were revived in Denmark because of the gigantic, ongoing Trier witch trials in Germany, which were described and discussed in Denmark.[58]

In Denmark, the admiral of the Danish fleet, Peder Munk argued with the treasurer Christoffer Valkendorff about the state of the ships of the bridal fleet, and blamed the mishaps on the wife of a high official in Copenhagen whom he had insulted. The Copenhagen witch trials were held in Denmark in July 1590.[59] One of the first Danish victims was Anna Koldings, who, under pressure, divulged the names of five other women; one of whom was Malin, the wife of the burgomaster of Helsingor. They all confessed that they had been guilty of sorcery in raising storms that menaced Queen Anne's voyage, and that on Halloween night they had sent devils to climb up the keel of her ship. In September, two women were burnt as witches at Kronborg.[60] James heard news from Denmark regarding this and decided to set up his own tribunal.

Agnes Sampson and John Fian

.jpg.webp)

According to the Newes from Scotland and the charges laid against her,[61] Agnes Sampson, one of the accused at North Berwick, a woman from Humbie or Nether Keith in the parish of Keith Marischal, confessed to causing the storm that drowned Jane Kennedy on 7 September 1589 when ferry boats collided during a sudden storm on the Forth. She had made a charm by sinking a dead cat, to which her companions had attached parts of a dead man, into the sea near Leith.[62] The same charm raised the storm and weather effects that threatened the king on his return voyage from Denmark in 1590.[63]

The 13th article of the "dittay", the 53 charges made against Agnes Sampson, was that she had fore-knowledge from the devil of a storm at Michaelmas; and the 14th, that a spirit advised her in advance that James would sail to meet to Anne of Denmark; the 40th to raise a wind to delay the queen's ship.[64]

Agnes Sampson used the phrase "contrary wind", and this frequently appears in contemporary correspondence describing voyages, but she used it in a special sense.[65] The record of her confession includes this phrase:

"The King's Majesties Ship had a contrary wind to the rest of ships, then being in his company, which thing was most strange and true, as the King's Majesty acknowledges, for when the rest of the Ships had a fair and good wind, then was the wind contrary and altogether against his Majesty"[66]

The rest of the fleet were able to sail ahead, while the king's ship alone was becalmed or driven back. This seems to be an incident described in the chronicle by David Moysie. When James VI set sail for Norway his ship was driven back to St Monans in Fife. Moysie wrote:

His Majestie with the rest should [have] made sail upone Sunday at afternoon, the 19 day of October instant, at which time there come on such a deadly storm, that the ships lying all in Leith road were shaken loose, and driven all up to St Margaret's Hope, and so the journey stayed for that night. Upone the 22 day of October, about twelve hours at even, his Majesty made sail to Norway with five ships in company: his Majesty was driven back 20 or 30 miles with great storm, and rode foranent (stopped beside) St Monans.[67]

Sailors in the Firth of Forth were used to stormy weather. The royal household books for 1529 record the loss of provisions and barrels of beer from a boat between Leith and Stirling, due to "a great wind from the north by Aberdour".[68]

Agnes Sampson is thought to have been a practising Catholic, following a faith then outlawed in Scotland as a recusant.[69] There were in total 53 charges or "articles of dittay" made against her.[70] According to the Scottish legal historian and antiquary Robert Pitcairn, writing in Ancient Criminal Trials, Agnes Sampson was executed for the crime of witchcraft on 27 January 1591 at the Castlehill in Edinburgh.[71]

The English ambassador, Robert Bowes obtained a note of her confession which states that the execution took place on the following day, 28 January. This note mentions 102 charges or "points of dittay" against Agnes Sampson and that another of the accused, John Fian alias Cunningham had confessed that she was involved in raising a storm at Leith and another to prevent the sailing of Anne of Denmark to Scotland. John Fian was indicted on the charge of "raising the winds at the King's passing to Denmark" and being present an assembly "where Satan promised to raise a mist" and drive the King's ship to England.[72] John Fian denied his own confession and was also executed.[73] The first assembly was alleged to have taken place at North Berwick, and the second at the "Pans", meaning the harbour of Prestonpans, then called "Acheson's Haven" and now known as Morrison's Haven.[74]

The royal voyages in state theatre

A paper written in defence of the Earl of Bothwell, accused of witchcraft and planning the death of James VI, possibly written in June 1591 by the kirk minister Robert Bruce of Kinnaird recounts the royal sea voyages:

her sailing hither was delayed by conjurations of devils and witches and by storms and tempests until the extreme affection and impatient passion of our invincible king led his unafraid courage to commit his crown and his corse (body) unto the raging winds and stormy seas like a new Jason to bring away the golden fleece despite the force of all the infernal powers and dragon devils.[75]

The concept that James VI and Anne of Denmark had been in peril at sea caused by the "conspiracies of witches" appeared in the Masque at the baptism of Prince Henry in August 1594 performed at Stirling Castle, when their good fortune was depicted by a ship in the Great Hall of Stirling Castle. The foresail of the ship was painted with a compass and the North Star, signifying the king's readiness to sail the oceans.[76] James VI was styled a "New Jason" by William Fowler, poet and secretary to Anne of Denmark, who had been with the couple in Denmark.[77] Fowler, his words echoing the letter of 1591, attributed the presentation of James VI as Jason and the ship to the king himself:[78]

The Kings Maiestie, hauing undertaken in such a desperate time, to sayle to Norway, and like a newe Iason, to bring his Queene our gracious Lady to this Kingdome, being detained and stopped by the conspiracies of Witches, and such devillish Dragons, thought it very meet, to followe foorth this his owne invention, that as Neptunus (speaking poetically, and by such fictions, as the like Interludes and actions are accustomed to be decored withall) ioyned the King to the Queene.[79]

The story of Jason and the Argonauts is told in Ovid's Metamorphoses and the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes. By analogy, Anne of Denmark was Medea and, as Clare McManus notes, she was also the Golden Fleece and the embodiment of her dowry.[80]

The masque was written by Anne of Denmark's Scottish secretary William Fowler and first published in 1594 by Robert Waldegrave as a kind of festival book, promoting the Scottish monarchy and its rights to English throne. Fowler wrote that the ship was the king's "own invention".[81] The symbolic ship was laden with Neptune's gift of all kinds of fish made from sugar, including herring, whiting, flounders, oysters, whelks, crabs and clams, served in Venetian glasses tinted with azure, which were distributed while Arion seated on a dolphin played his harp. Some Latin verses in praise of Anne were sung, followed by Psalm 128 in canon with musical accompaniment.[82] The imitation sugar fish and serving glasses were provided by a Flemish confectioner Jacques de Bousie and the court sommelier, Jerome Bowie.[83]

When he was in Denmark, James VI promised Anne's brother, the young Christian IV, that he would return for his coronation in Copenhagen.[84] When the time came in 1596, James made his excuses, saying it was not the time to travel, when Anne was pregnant and "unable to bear the tossing of a voyage and sea-sickness", or the absence of a husband, if he were to travel alone.[85]

Apology from Scottish Government

In March 2022 Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister of Scotland, apologized for the persecution of alleged witches during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. The Scottish Government had not apologized previously.[86] In her speech to the Scottish Parliament, Nicola Sturgeon explained:

Firstly, acknowledging injustice, no matter how historic is important. This parliament has issued, rightly so, formal apologies and pardons for the more recent historic injustices suffered by gay men and by miners.

Second, for some, this is not yet historic. There are parts of our world where even today, women and girls face persecution and sometimes death because they have been accused of witchcraft.

And thirdly, fundamentally, while here in Scotland the Witchcraft Act may have been consigned to history a long time ago, the deep misogyny that motivated it has not. We live with that still. Today it expresses itself not in claims of witchcraft, but in everyday harassment, online rape threats and sexual violence.[87]

References

- Maurice Lee jnr., John Maitland of Thirlestane and the Foundation of the Stewart Despotism in Scotalnd (Ptinceton UP, 1959), p. 225.

- Maureen Meikle, 'A meddlesome princess: Anna of Denmark and Scottish court politics, 1589-1603', Julian Goodare & Michael Lynch, The Reign of James VI (East Linton: Tuckwell, p. 130.

- Edward J. Cowan, 'The Darker Version of the Scottish Renaissance: the Devil and Francis Stewart', Ian B. Cowan & Duncan Shaw, Renaissance and Reformation in Scotland: Essays in honour of Gordon Donaldson (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1983), pp. 125-140.

- Susan Dunn Hensley, Anna of Denmark and Henrietta Maria: Virgins, Witches, and Catholic Queens (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 46-51, 56.

- Liv Helene Willumsen, 'Witchcraft against Royal Danish Ships in 1589 and the Transnational Transfer of Ideas', IRSS, 45 (2020), pp. 54-99

- Steven Veerapen, The Wisest Fool: The Lavish Life of James VI and I (Birlinn, 2023), p. 134: David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh, 1997), p. 86: Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 150, 164.

- Kancelliets brevbøger vedrørende Danmarks indre forhold i uddrag (Copenhagen, 1908), pp. 242-3: Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 289.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh, 1997), p. 86.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh, 1997), pp. 86-7.

- Ethel Carleton Williams, Anne of Denmark (London, 1970), p. 16.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh, 1997), p. 86.

- James Dennistoun, Moysie's Memoirs of the Affairs of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1830), p. 79

- George Akrigg, Letters of King James VI & I (University of California, 1984), p. 95.

- Sebastiaan Verweij, The Literary Culture of Early Modern Scotland: Manuscript Production and Transmission (Oxford, 2016), pp. 60-1: Jane Rickard, Authorship and Authority in the writings of James VI and I (Manchester, 2007), pp. 56-60: Sarah Dunnigan, Eros and Poetry at the Courts of Mary Queen of Scots and James VI (Basingstoke, 2002), pp. 77-104.

- Sarah Dunnigan, Eros and Poetry at the Courts of Mary Queen of Scots and James VI (Basingstoke, 2002), pp. 81-2 citing British Library Add. MS 24195.

- David M. Bergeron, The Duke of Lennox, 1574-1624: A Jacobean Courtier's Life (Edinburgh, 2022), pp. 16-18: Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 150, 164.

- Liv Helene Willumsen, 'Witchcraft against Royal Danish Ships in 1589 and the Transnational Transfer of Ideas', IRSS, 45 (2020), p. 60: David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Wedding (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997), p. 26.

- Maureen Meikle, 'A meddlesome princess: Anna of Denmark and Scottish court politics, 1589-1603', Julian Goodare & Michael Lynch, The Reign of James VI (East Linton: Tuckwell, 2000), p. 127.

- Miles Kerr-Peterson & Michael Pearce, 'James VI's English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts', Scottish History Society Miscellany XVI (Woodbridge, 2020), pp. 10, 93-4

- Miles Kerr-Peterson & Michael Pearce, 'James VI's English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts', Scottish History Society Miscellany XVI (Woodbridge, 2020), p. 93: Steven Veerapen, The Wisest Fool: The Lavish Life of James VI and I (Birlinn, 2023), p. 136: HMC Salisbury Hatfield, vol. 3 (London, 1889), p. 438: British Library Add MS 19401 ff.141-3 copies in the Rigsarkivet are dated 3 October 1589.

- William Dunn Macray, 'Report on Archives in Denmark', 46th Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records (London, 1886), p. 32: See also BL Cotton Caligula D/I f.273.

- Liv Helene Willumsen, 'Witchcraft against Royal Danish Ships in 1589 and the Transnational Transfer of Ideas', IRSS, 45 (2020), p. 66.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Wedding (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997), p. 28.

- David Masson, Register of the Privy Council, Addenda 1540-1625 (Edinburgh, 1898), pp. 370-1.

- Miles Kerr-Peterson & Michael Pearce, 'James VI's English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts', Scottish History Society Miscellany XVI (Woodbridge, 2020), pp. 10, 93-4.

- Robert Vans-Agnew, Correspondence of Sir Patrick Waus of Barnbarroch, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1887), pp. 452-3.

- William King Tweedie, Select Biographies, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1845), p. 308

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Wedding (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997), p. 127 fn. 5.

- Ethel Carleton Williams, Anne of Denmark (London, 1970), pp. 20, 207 fn. 20.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997), pp. 30, 34, 87, 90.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997), p. 34: Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 160-162: Annie Cameron, Calendar State Papers Scotland, 1593-1595, vol. 11 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 92 no. 62.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 197 no. 268.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1997), p. 34 citing James Melville, Autobiography and Diary (Edinburgh, 1842), p. 277

- Lucinda H. S. Dean, '"richesse in fassone and in fairness": Marriage, Manhood and Sartorial Splendour for Sixteenth-century Scottish Kings', Scottish Historical Review(December 2021), p. 393: Miles Kerr-Peterson & Michael Pearce, 'James VI's English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts', Scottish History Society Miscellany XVI (Woodbridge, 2020), p. 37 & fn. 76.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 205 no. 299.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh, 1997), p. 95.

- David Masson, Register of the Privy Council: 1585-1592, vol. 4 (Edinburgh, 1881), pp. 444-5.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 221-2 no. 327.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh, 1997), pp. 36, 44-5, 92.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh, 1997), p. 45 citing James Melville, Autobiography and Diary of Mr James Melville (Edinburgh, 1842), p. 277

- Miles Kerr-Peterson & Michael Pearce, 'James VI's English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts', Scottish History Society Miscellany, XVI (Woodbridge, 2020), pp. 42-43 & fn.105.

- George Akrigg, Letters of King James VI & I (University of California, 1984), p. 108.

- Marguerite Wood, Extracts from the Records of the Burgh of Edinburgh, 1589-1603 (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1927), pp. 17, 330.

- Eva Griffith, A Jacobean Company and its Playhouse: The Queen's Servants at the Red Bull Theatre (Cambridge, 2013), p. 115: Maureen Meikle, 'Once A Dane, Always A Dane?', Court Historian, 24:2 (2020), p. 170

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 284-5 no. 327.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 165-6, letters of William Ashby to Walsingham and William Cecil.

- Robert Pitcairn, Ancient Criminal Trials (Edinburgh, 1833), pp. 185-186.

- Thomson, Thomas, ed., Memoirs of his own life by James Melville (Edinburgh, 1827), pp. 369-70.

- Liv Helene Willumsen, 'Witchcraft against Royal Danish Ships in 1589 and the Transnational Transfer of Ideas', IRSS, 45 (2020), pp. 54-99 at pp. 62-3

- William Fraser, Melvilles, Earls of Melville, and the Leslies, Earls of Leven (Edinburgh, 1890), p. 167: HMC 9th Report: Traquair House, (London, 1884), p. 252.

- Exchequer Rolls, XXII (Edinburgh, 1903), p. 56.

- G. F. Warner, Library of James VI (Edinburgh, 1893), p. xlviii.

- David Stevenson, Scotland's Last Royal Wedding (Edinburgh, 1997), pp. 49, 99, 131.

- Edward J. Cowan, 'The Darker Version of the Scottish Renaissance: the Devil and Francis Stewart', Ian B. Cowan & Duncan Shaw, Renaissance and Reformation in Scotland: Essays in honour of Gordon Donaldson (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1983), p. 129.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 348.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 365.

- Maurice Lee, John Maitland of Thirlestane (Princeton University Press, 1959), p. 229.

- Kallestrup, Louise Nyholm: Heksejagt. Aarhus Universitetsforlag (2020)

- Ankarloo, B., Clark, S. & Monter, E. W. Witchcraft and Magic in Europe. p. 79

- Ethel Carleton Williams, Anne of Denmark (London, 1970).

- James Thomson Gibson-Craig, Papers Relative to the Marriage of James VI (Edinburgh, 1828), pp. xiv-xv

- Angelo S. Rappoport, Superstitions of Sailors (London, 1928), p. 49.

- Newes from Scotland (Roxburghe Club: London, 1816), sig. B3.

- Robert Pitcairn, Ancient Criminal Trials (Edinburgh, 1833), pp. 231-241

- Liv Helene Willumsen, 'Witchcraft against Royal Danish Ships in 1589 and the Transnational Transfer of Ideas', IRSS, 45 (2020), pp. 54-99

- James Craigie & Alexander Law, Minor Prose Works of James VI and I (Scottish Text Society, Edinburgh, 1982), p. 151, modernised here.

- James Dennistoun, Moysie's Memoirs of the Affairs of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1830), p. 80 modernised here.

- Excerpta e libris domicilii Jacobi Quinti regis Scotorum (Bannatyne Club: Edinburgh, 1836), Appendix p. 24.

- Edward J. Cowan, 'The Darker Version of the Scottish Renaissance: the Devil and Francis Stewart', Ian B. Cowan & Duncan Shaw, Renaissance and Reformation in Scotland: Essays in honour of Gordon Donaldson (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1983), p. 128.

- James Thomson Gibson-Craig,Papers relative to the marriage of King James the Sixth of Scotland, with the Princess Anna of Denmark (Edinburgh, 1836), p. xiv

- James Craigie & Alexander Law, Minor Prose Works of James VI and I (Scottish Text Society, Edinburgh, 1982), p. 152 citing Pitcairn, Ancient Criminal Trials (Edinburgh, 1833), vol. 2, pp. 241, 348.

- James Craigie & Alexander Law, Minor Prose Works of James VI and I (Scottish Text Society, Edinburgh, 1982), pp. 151-2, citing Robert Picairn, Criminal Trials, vol. 1 part 2 (1833), p. 211.

- William Boyd & Henry Meikle, Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), pp. 461, 464-7 no. 526.

- P. G. Maxwell-Stuart, Satan's Conspiracy: Magic and Witchcraft in Sixteenth-century Scotland (Tuckwell: East Linton, 2001), pp. 146-7: Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 530.

- Annie Cameron, Warrender Papers, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: SHS, 1932), p. 156.

- Henry Meikle, The Works of William Fowler, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: STS, 1936), p. 192 See also, Jamie Reid Baxter, 'Scotland will be the Ending of all Empires', Steve Boardman & Julian Goodare, Kings, Lords and Men in Scotland and Britain (Edinburgh, 2014), pp. 332-4.

- Clare McManus, Women on the Renaissance Stage: Anna of Denmark and Female Masquing in the Stuart Court, 1590-1619 (Manchester, 2002), p. 87.

- David M. Bergeron, The Duke of Lennox, 1574-1624: A Jacobean Courtier's Life (Edinburgh, 2022), p. 46.

- William Fowler, A true reportarie of the most triumphant, and royal accomplishment of the baptisme of the most excellent, right high, and mightie prince, Frederik Henry; by the grace of God, Prince of Scotland Solemnized the 30 day of August 1594 (Edinburgh, 1594): Henry Meikle, Works of William Fowler, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1936), p. 193

- Clare McManus, Women on the Renaissance Stage: Anna of Denmark and Female Masquing in the Stuart Court, 1590-1619 (Manchester, 2002), p. 88.

- Henry Meikle, The Works of William Fowler, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: STS, 1936), pp. 169–95

- Thomas Thomson, History of the Kirk of Scotland by Mr David Calderwood, vol. 5 (Edinburgh, 1844), p. 345.

- Miles Kerr-Peterson & Michael Pearce, 'James VI's English Subsidy and Danish Dowry Accounts', Scottish History Society Miscellany XVI (Woodbridge, 2020), p. 80.

- Calendar State Papers Scotland, 1595-1597, vol. 12 (Edinburgh, 1952), p. 181 no. 151.

- William Dunn Macray, 'Report on Archives in Denmark', 47th Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records (London, 1886), p. 38

- Cramer, Maria (9 March 2022). "Scotland Apologizes for History of Witchcraft Persecution". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- Libby Brooks, 'Nicola Sturgeon issues apology for 'historical injustice' of witch hunts', Guardian, 8 March 2022

External links

- Liv Helene Willumsen, Witchcraft Against Royal Danish Ships in 1589 and the Transnational Transfer of Ideas, IRSS, 45 (2020), pp. 54-99

- Rigsarkivet, Copies of Anne of Denmark's letters, 3 October 1589, with slight differences, VA XI, Tyske Kancelli II, s. 285 TKUA, Speciel del, Skotland 5

- 'Agnes Sampson', Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939), 'The Dinner Party' (Heritage Floor; detail), 1974–79, Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation

- University of Glasgow Library, Newes from Scotland, Exhibition, 2000

- Edinburgh Evening News, 'Agnes Sampson: Who was the famous East Lothian midwife, and how was she accused, and then murdered, for witchcraft in Scotland?', Rachel Mackie, 8 March 2022

- VoiceMap Location 5 | A HISTORY OF WITCHCRAFT IN SCOTLAND: FROM HOLYROOD PALACE TO EDINBURGH CASTLE, Agnes Sampson

- Michael Bath, 'Rare Shewes, the Stirling Baptism of Prince Henry' in Journal of the Northern Renaissance, no. 4, 2012