Ankhesenamun

Ankhesenamun (ˁnḫ-s-n-imn, "Her Life Is of Amun"; c. 1348[1] or c. 1342 – after 1322 BC[2]) was a queen who lived during the 18th Dynasty of Egypt as the pharaoh Akhenaten's daughter and subsequently became the Great Royal Wife of pharaoh Tutankhamun. Born Ankhesenpaaten (ˁnḫ.s-n-pꜣ-itn, "she lives for the Aten"),[3] she was the third of six known daughters of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti. She became the Great Royal Wife of Tutankhamun.[4] The change in her name reflects the changes in ancient Egyptian religion during her lifetime after her father's death. Her youth is well documented in the ancient reliefs and paintings of the reign of her parents. The mummy of Tutankhamun's mother has been identified through DNA analysis as a full sister to his father, the unidentified mummy found in tomb KV55, and as a daughter of his grandfather, Amenhotep III. So far his mother's name is uncertain, but her mummy is known informally to scientists as the Younger Lady.[5]

| Ankhesenamun | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great Royal Wife | |||||||

Sculpture fragment believed to be of Ankhesenamun, Brooklyn Museum, United States | |||||||

| Tenure | c. 1332–1323 BC | ||||||

| Born | c. 1348 BC[1] or c. 1342 BC[2] Thebes | ||||||

| Died | after 1322 BC (aged 20-26)[2] | ||||||

| Burial | KV21 (uncertain) | ||||||

| Spouse | Tutankhamun (half-brother or cousin) Ay (grandfather or great-uncle?) | ||||||

| Issue | 317a and 317b (uncertain) Ankhesenpaaten Tasherit (uncertain) | ||||||

| Egyptian name | |||||||

| Dynasty | 18th of Egypt | ||||||

| Father | Akhenaten | ||||||

| Mother | Nefertiti | ||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian religion | ||||||

Ankhesenamun was well documented as being the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Tutankhamun. Initially, she may have been married to her father and it is possible that, upon the death of Tutankhamun, she was married briefly to Tutankhamun's successor, Ay, who is believed by some to be her maternal grandfather.[6]

DNA test results on mummies discovered in KV21 were released in February 2010, which has given rise to speculation that one of two late 18th Dynasty queens buried in that tomb could be Ankhesenamun. Because of their DNA, both mummies are thought to be members of that ruling house.[5]

Early life

| Ankhesenpaaten in hieroglyphs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ˁnḫ.s-n-pꜣ-itn Living for Aten | ||||||||

Ankhesenpaaten was born in a time when Egypt was in the midst of an unprecedented religious revolution (c. 1348 BC). Her father had abandoned the principal worship of old deities of Egypt in favor of the Aten, hitherto a minor aspect of the sun-god, characterised as the sun's disc.

She is believed to have been born in Thebes, around year 4 of her father's reign, but probably grew up in the city of Akhetaten (present-day Amarna), established as the new capital of the kingdom by her father. The three eldest daughters – Meritaten, Meketaten, and Ankhesenpaaten – became the "senior princesses" and participated in many functions of the government and religion alongside their parents.

Later life

She is believed to have been married first to her own father,[7] which was not unusual for Egyptian royal families. She is thought to have been the mother of the princess Ankhesenpaaten Tasherit (possibly by her father or by Smenkhkare), although the parentage is unclear.[4]

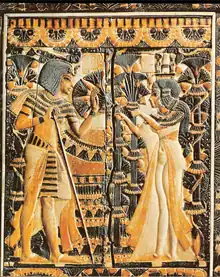

After her father's death and the short reigns of Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten, she became the wife of Tutankhamun. Following their marriage, the couple honored the deities of the restored religion by changing their names to Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun.[8] The couple appear to have had two stillborn daughters.[5] As Tutankhamun's only known wife was Ankhesenamun, it is highly likely the fetuses found in his tomb are her daughters. Some time in the 9th year of his reign, about the age of 18, Tutankhamun died suddenly, leaving Ankhesenamun alone and without an heir about the age 21.[8]

A blue glass ring of unknown provenance obtained in 1931 depicts the prenomen of Ay and the name of Ankhesenamun enclosed in cartouches.[9] This indicates that Ankhesenamun married Ay shortly before she disappeared from history, although no monuments show her as great royal wife to him.[10] On the walls of Ay's tomb it is Tey (Ay's senior wife), not Ankhesenamun, who appears as his great royal wife. She probably died during or shortly after his reign and no burial has been found for her yet.

Hittite letters

A document was found in the ancient Hittite capital of Hattusa dating back to the Amarna period. The document — part of the so-called Deeds of Suppiluliuma I — relates that Hittite ruler, Suppiluliuma I, while laying siege to Karkemish, received a letter from the Egyptian queen. The letter reads:

My husband has died and I have no son. They say about you that you have many sons. You might give me one of your sons to become my husband. I would not wish to take one of my subjects as a husband... I am afraid.[11]

This document is considered extraordinary, as Egyptians traditionally considered foreigners to be inferior. Suppiluliuma I was amazed and exclaimed to his courtiers:

Nothing like this has happened to me in my entire life![12]

Understandably, he was wary and had an envoy investigate, but by delaying, he missed his apparent opportunity to bring Egypt into his empire. He eventually did send one of his sons, Zannanza, but the prince died en route, perhaps being murdered.[13]

The identity of the queen who wrote the letter is uncertain. In the Hittite annals, she is called Dakhamunzu, a transliteration of the Egyptian title, Tahemetnesu (The King's Wife).[14] Possible candidates for the author of the letter are Nefertiti, Meritaten,[6] and Ankhesenamun. Ankhesenamun once seemed likely since there were no royal candidates for the throne on the death of her husband, Tutankhamun, whereas Akhenaten had at least two legitimate successors. But this was based on a 27-year reign for the last 18th dynasty, pharaoh Horemheb, who is now accepted to have had a shorter reign of only 14 years. Since Nefertiti was depicted as powerful as her husband in official monuments smiting Egypt's enemies, researcher Nicholas Reeves believes she might be the Dakhamunzu in the Amarna correspondence.[15] That would make the subject deceased Egyptian king appear to be Akhenaten rather than Tutankhamun. As noted, Akhenaten had potential heirs, including Tutankhamun, to whom Nefertiti could be married. Other researchers focus upon the phrase regarding marriage to 'one of my subjects' (translated by some as 'servants') as possibly a reference to the Grand Vizier Ay or a secondary member of the Egyptian royal family line, however, and that Ankhesenamun may have been being pressured by Ay to marry him and legitimize his claim to the throne of Egypt (which she eventually did).[16]

Mummy KV21A

DNA testing announced in February 2010 has generated speculation that Ankhesenamun is one of two 18th Dynasty queens recovered from KV21 in the Valley of the Kings.[17]

The two fetuses found buried with Tutankhamun have been proven to be his children, and the current theory is that Ankhesenamun, his only known wife, is their mother. However, not enough data was obtained to make more than a tentative identification. Nevertheless, the KV21a mummy has DNA consistent with the 18th Dynasty royal line.[17]

KV63

After excavating the tomb KV63, it is speculated that it was designed for Ankhesenamun due to its proximity to the tomb of Tutankhamun, KV62. Also found in the tomb were coffins (one with an imprint of a woman on it), women's clothing, jewelry, and natron. Fragments of pottery bearing the partial name Paaten were also in the tomb. The only royal person known to bear this name was Ankhesenamun, whose name was originally Ankhesenpaaten. However, no mummies were found in KV63.

Popular culture

Ankhesenamun's name has entered popular culture as the secret love of the priest Imhotep in the 1932 film The Mummy. The 1999 remake, its sequel and its spin-off television series used the name Anck-su-namun, while other movies like The Mummy's Hand (1940) [18] and the 1959 remake named the character Ananka.[19]

Ancestry and family

References

- Arnold, Dorothea; Allen, James P.; Green, L. (1996). The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt (Hardback ed.). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. xviii. ISBN 0-87099-816-1. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- Galassi, F. M.; Ruhli, F. J.; Habicht, M. E. (2016). "Did Queen Ankhesenamun (c. 1342 - after 1322 BC) have a goitre?: Historico-clinical Reflections upon a paleo-pathographic study". Working Paper. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3356.5843. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- Ranke, Hermann (1935). Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, Bd. 1: Verzeichnis der Namen (PDF). Glückstadt: J.J. Augustin. p. 67. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Dodson, Aidan; Dyan Hilton (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 148.

- Hawass, Zahi; et al. (2010). "Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (7): 638–647. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121. PMID 20159872.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2000). Ancient Egyptian Queens; a hieroglyphic dictionary. London: Golden House. p. 64.

- Reeves, Nicholas (2001). Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 9780500051061.

- "Queen Ankhesenamun". Saint Louis University. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- Newberry, Percy E. (May 1932). "King Ay, the Successor of Tut'ankhamun". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 18 (1/2): 50–51. doi:10.2307/3854904. JSTOR 3854904.

- Dodson, Aidan; Dyan Hilton (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 153.

- Güterbock, Hans Gustav (June 1956). "The Deeds of Suppiluliuma as Told by His Son, Mursili II (Continued)". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 10 (3): 75–98. doi:10.2307/1359312. JSTOR 1359312. S2CID 163670780.

- Güterbock, Hans Gustav (1956). "The Deeds of Suppiluliuma as Told by His Son, Mursili II". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 10 (2): 41–68. doi:10.2307/1359041. JSTOR 1359041. S2CID 163922771.

- Amelie Kuhrt (1997). The Ancient Middle East c. 3000 – 330 BC. Vol. 1. London: Routledge. p. 254.

- Federn, Walter (January 1960). "Daḫamunzu (KBo V 6 iii 8)". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 14 (1): 33. doi:10.2307/1359072. JSTOR 1359072. S2CID 163447190.

- Nicholas Reeves,Tutankhamun's Mask Reconsidered BES 19 (2014), pp.523

- Christine El Mahdy (2001), "Tutankhamun" (St Griffin's Press)

- Hawass, Zahi; Gad, Yehia Z.; Somaia, Ismail; Khairat, Rabab; Fathalla, Dina; Hasan, Naglaa; Ahmed, Amal; Elleithy, Hisham; Ball, Markus; Gaballah, Fawzi; Wasef, Sally; Fateen, Mohamed; Amer, Hany; Gostner, Paul; Selim, Ashraf; Zink, Albert; Pusch, Carsten M. (February 17, 2010). "Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family". Journal of the American Medical Association. Chicago, Illinois: American Medical Association. 303 (7): 638–647. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121. ISSN 1538-3598. PMID 20159872. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Mengel, Brad (2023-01-02). The Unofficial Guide to The Scorpion King and The Mummy Universe. BearManor Media.

- Pfeiffer, Oliver (April 21, 2017). "Where does the legend of the mummy come from?". BBC. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

Further reading

- Akhenaten, King of Egypt by Cyril Aldred (1988), Thames & Hudson

External links

Media related to Ankhesenamun at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ankhesenamun at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)