Animals in ancient Greece and Rome

Animals had a variety of roles and functions in ancient Greece and Rome. Fish and birds were served as food. Species such as donkeys and horses served as work animals. The military used elephants. It was common to keep animals such as parrots, cats, or dogs as pets. Many animals held important places in the Graeco-Roman religion or culture. For example, owls symbolized wisdom and were associated with Athena. Humans would form close relationships with their animals in antiquity. Philosophers often debated about the nature of animals and humans. Many believed that the fundamental difference was that humans were capable of reason while animals were not. People such as Porphyry advocated for veganism.

Marine life

Fishing

For the ancient Greeks and Romans fishing served as a source of income, food, and entertainment.[1] Fishes such as tuna,[2] sturgeons,[3] mackerel,[4] jellyfish,[5][6][7] anchovies,[8] lobsters, sprat, red mullet, oysters, mussels, sea urchins, salted fish,[9] squid,[10] and octopus were popular meals in ancient Greece or Rome.[11] Octopuses were stored in pots and they would be given as a gift.[12] Fish was also used to make a popular condiment known as garum. Species such as Bluefin Tuna were expensive delicacies in ancient Greece.[13][14][15] In ancient Rome, many fish species were delicacies.[16] The poor had limited access to these fish.[17] Fishes were also used to help guide seamen and as methods of foretelling the weather.[18]

Ancient fisherman used nets,[19] short rods,[20] traps, and lines with hooks.[21][22][23] Roman fishing lines would often have an artificial fly attached to the end of the line. These flies were made of small feathers and were made to imitate the insects that landed on the surface of the water. The ancient Greek word griphos referred to a type of fishing basket.[24] Poseidon, or Neptune in Roman mythology carried a trident that is used for spearfishing.[25] People would hunt and trap tuna through seine fishing.[26] Traps such as the almadraba might have been used in ancient Rome.[27] Fisherman would sell their goods in the markets of Roman cities for profit.[28][29] There were thriving fish markets across the Roman world.[30]

Polybius describes fishing techniques in his works. Boats would sail towards the fishing spot, with one sailor serving as a lookout. The lookout would signal to the other sailors when they had found fish. One sailor would row the boat towards the fish, while another man stood by ready to harpoon the fish. After the fish was stabbed the harpooner would pull the weapon out of the body leaving behind the barbed spear point inside of the fish. The fisherman attached a rope to the spear point, which they would then use to pull the fish towards them.[31] Oppian, a Greek writer who wrote the Halieutica describes fishing in his work. He wrote that fisherman would use their oars to scare the fish into running into their nets made of buoyant flax. Which the fish thought was shelter.[32] In ancient Athens a bell would announce the arrival of fishing boats.[33] The ancient Greeks and Romans practiced whaling. They hunted both sperm and killer whales. Usually, they would whale by Corsica, Sardinia, and the Peloponnese. Ancient whaling was a dangerous practice and whalers used long lines with animals skins at the end to catch the whale and prevent themselves from being dragged under by it.[34]

Stories of fishermen and fishing appear throughout Ancient Greek literature. For example, in Sophron's The Fisherman and the Clown or the comedian Plato's Phaon.[35] Roman and Greek writers were infatuated with the idea of a weather-beaten fisherman.[36] Oppian depicted the fisherman as heroic.[37][38] The Greeks and Romans practiced aquaculture and would create artificial bodies of water for fish.[39] Sometimes they would keep fish as pets.[34] Alcaeus, a Greek lyric poet wrote:[35]

The fisherman Diotimus had at sea

And shore the same abode of poverty-

His trusty boat-and when his days were spent,

Therein self-rowed, to ruthless Dis he went:

For which did through life his woes beguile,

Supplied the old man with a funeral pile.

Dolphins and whales

Pliny the Elder described a story of a boy who befriended a dolphin by feeding him bread.[40][41] The ancient Greeks had numerous stories of people being rescued by dolphins. Arion, a Greek musician, and Dionysus, a Greek god both had such stories told about them.[42] The Romans called dolphins porcus piscus, which translates to pig-fish.[43] During the reign of Septimius Severus, a whale was stranded on the Tiber River. The Romans built a model of this whale, which people would walk through. This site became a popular tourist attraction. People would watch animals such as lions walk through the model.[44]

Lobsters

Although there are a wide variety of images of lobsters throughout ancient Greece or Rome,[45] very few are anatomically accurate. The ancient Romans knew that lobsters had five arms and they had detailed information about their claws and other external features. Pliny considered them bloodless animals.[46] The Romans also knew that lobsters live in rocky terrain, their reproductive habits, and their seasonal movements. Roman authors provide accounts of how lobsters interacted with octopuses, which are their predators.[47] Fishermen used this information to catch the lobsters using lobster traps. Which became a popular metaphor in Roman theatre.[48] Lobsters were considered a prestigious food in ancient Rome and Greece and the wealthy would hunt them to gather them.[49]

Other species

Seaweed was known as alga in ancient Rome and the Greeks knew it as phycos.[50] In ancient Rome it was considered a medicine for gout and ankle swelling. Roman poet Virgil wrote, "nothing is more vile than seaweed." Juvenal, another Roman poet, once joked about "inspectors of seaweed," who waste time on trivial matters.[51] The Romans would wrap the roots of their crops with seaweed to preserve the freshness and humidity of the seedlings.[52][53][54] Red algae were also used as soil fertilizer in ancient Rome.[55] Dioscorides described the usage of algae as medicine in De Materia Medica.[56] Several species of venus clam, or as they were called in Greek, kheme. One species was the kheme trakheia or the glykymaris. They were known for their hard shells, taste similar to the sea, and high level of nutrition. The khemea leia, or the smooth clam was known for its smoothness and taste. Another species, known as peloris, is possibly named after Cape Peloris, which is where they were found.[57] Saltfish were used in Roman medicine. They were believed to provoke the bowels and the appetite. It was considered difficult to digest, although nutritious. Xenocrates differentiates between a variety of kinds of saltfish. One kind had hard flesh, another kind had soft flesh, another kinds had flesh somewhere in between. Some saltfish were fleshy and others were fatty. The fat saltfish were capable of floating on their stomach.[58]

Birds

.jpg.webp)

Birds in ancient Rome and Greece were eaten as food. Flamingo tongues were highly valuable in ancient Rome. Emperors would collect them and serve them at feasts.[59] The Hēliou Zōön, or "creature of the sun" was an ancient Greek term for a species of bird, which was likely the Greater Flamingo or the Phoenix.[60] Pheasants and geese were valuable delicacies in ancient Rome.[61][62][63] They, along with guineafowl and partridges were farmed. Partridges were considered good for people with dysentery.[64] Quails have been hunted since antiquity and eaten as food.[65] Ostrich eggs were also eaten, although rarely.[66]

The Romans ate peacocks and peahens. They usually were pastured in fields and were sacrificed to Juno and lived in temples. Through Juno, they became associated with marriage and fertility.[66] The arrival of a Barn Swallow was believed to be a signal that spring had arrived. This belief is the origin of an ancient proverb “One Swallow doesn’t make a spring. Swallow chicks are hatched blind, which may have led to an ancient misconception that if the eyes of a chick was removed, they would heal and would be granted sight. Swallows also appear in Greek myths such as with Procne and Philomela.[67] Red and Black Kites were thought of as a sign of spring and a marker that was used by farmers to determine when they should shear their sheep. It was also considered to be a greedy and malevolent animal that killed young children and stole from the people.[68] The Eurasian Wryneck was connected with erotic magic in Ancient Rome and Greece. There are several explanations for this. One holds that the Wryneck was invented by Aphrodite to help Jason win Medea. Another is that Hera turned the daughter of Echo into a wryneck because of her affairs with Zeus.[69] One bird, which is possibly the Ruff was known for traveling to the grave of Memnon and then killing each other.[70] Bats were thought to have mythical properties.

Tits, or as they were known in ancient Greece, Aigthalos,’’ were said to have laid more eggs than other birds and to have attacked bees and wasps. Which may have formed half their diet. This formed the origin for an Ancient Greek proverb, “Bolder than an Aigthalos.” Sometimes two females of this species were said to have laid in the same nest.[71] The Aigiothos or Aigithos is a bird described by Aristotle as fighting a war against donkeys. Donkeys rub their sides on thorn bushes which hide the nests and eggs of the bird, thus destroying them. The birds would peck the sores on the donkey’s back. This species is described as producing many children and being lame in one foot. It may have been a White wagtail, a Western Yellow wagtail, or a Northern Lapwing.[72] The Yellow Wagtail was valued for its usage to farmers.[73] If Jackdaws screamed it was considered a sign of oncoming rain. However, if they screamed following a storm it was a sign of good weather. [74] Ravens were also used as messengers of the weather.[75] The Black Francolin bird became a word for a branded runaway slave because of its color and its ability to conceal itself.[76] "Kepphos" was slang for an idiot in ancient Athens. This is because it was also the name of a bird which may be the European Storm Petrel. It was considered stupid as it fed on sea foam, and therefore hunters could catch it by throwing sea foam at it. [77] Emperor Claudius had a pet thrush which could replicate human speech.[78]

Owls

Aeiskops was the Greek for the Scops owl. Aristotle called the Scops Owls that lived in Greece all year-long “Always-Scops Owls.” These owls were inedible, while the ones that only stayed in Greece for only a couple of days were considered nutritious. These species were silent and fatter while the other species was loud and skinnier.[79] The Aigolios was a bird said to be the size of a domesticated chicken. Aristotle wrote that it hunted Jays and fed at night. Therefore, it was rarely visible during the day. It may have lived in caves and rocks. This species may have been the Ural Owl.[80] Owls were associated with Athena and wisdom.[81][82][83] Due to this association, the Acropolis was a safe haven for them. They were signs of victory and were believed to protect soldiers. Owls were also thought to watch over the Greek economy. The Greeks also believed that owls were capable of foretelling weather.[84] The early Romans believed that if one nailed a dead owl to a door it would protect that house from death. Owls signified death and defeat.[85] In ancient Rome, the Eagle Owl or Little Owl were believed to signify the imminent death of any person related to a house they landed on.[86] Ascalaphos, an ancient Greek mythological figure was turned into an owl by Demeter as punishment for informing her that Persephone had eaten pomegranate seeds in the underworld.[87]

Chickens

The Junglefowl was domesticated by the ancient Greeks. It may have arrived during the seventh century BCE from Persia. From this, it may have earned its name "The Persian bird." Chickens were used in cock fights and became known as Alektōr, which means "repeller" because of this. Cock fights were a popular sport throughout all of antiquity. Their practice of crowing around daybreak became a wake-up call. Live chickens were also used as gifts for lovers. Beginning in the Sixth Century BCE the Romans began to use chickens as farm animals. The Romans may have introduced chickens to Britain. Pliny wrote that the best hens had an upright comb, uneven claws, black feathers, and red beaks. The ancient Romans and Greeks had detailed knowledge of Chicken biology and behavior.[88] Chickens were also relevant to classical religion. Athena had a helmet with a chicken on it and people partaking in the Eleusinian mysteries were forbidden from eating chickens. Cockfights were important to Dionysus.[89]

Marine birds

Geese were domesticated by the ancient Greeks and Romans. They were kept as pets and eaten as food. Geese also appeared in mythology and folklore. The Charites had chariots driven by geese and they appeared in many of Aesop's fables.[66] Geese also allegedly helped save Rome during the Gaul's sack of Rome with their loud noises. For this, they were valued as guards.[90] Swans were believed to be the servants of Apollo and to release a beautiful song when near death.[91][92] Mallards were domesticated by the ancient Romans.[64] Aristotle describes a seabird known in Greece as the Aithyia or the Mergus in ancient Rome. It was believed to be native to Greece and to have reproduced by laying two or three eggs after the spring solstice in coastal rocks. Roman writers noted that this bird sometimes lived in trees or on rocks. In ancient Greece, this bird was known for diving into the sea. The Romans later wrote that it only did so to dive after oily fish such as eels. They have been identified as shearwaters, European Shags, or the Great Cormorant.[93] Cory's Shearwater is a species of bird that may have been the Diomēdeios Ornis, or the Bird of Diomedes. Which is an ancient Greek term for a bird which was said to have been Greek warriors under the command of Diomedes that were transformed into birds after being killed by Illyrians.[94] One species of seabird known as the Chandrios was believed to be capable of curing jaundice if the patient looked at the bird in the eyes. This species may be the Stone Curlew.[95] Greek and Roman farmers and sailors used Cranes as markers of time before the invention of the calendar.[96] Storks were associated with family and were believed to take good care of their family. The ancient Greeks and Romans would describe trustworthy people as behaving like storks. Their honesty was believed to lead the birds to be transformed into humans at the end of their lives.[97] An ancient Roman law known as the Lex Ciconia required that people care for their elderly.[98]

Foreign birds

Aelian describes a bird he calls the Agreus. Which, according to him, is a black bird that sings a song to lure in prey. It may have been a bird species belonging to the Indian Mynas, however, it is not described as a foreign word. Other possibilities are that is a Ring Ouzel or a Masked Shrike.[99] He also writes about two other Indian birds. One of which, which may be the Scarlet Finch, was described as being as red as flame and flying in such large numbers that people would mistake them for clouds. Another species was described as having a beautiful song and being colored like a rainbow. It may be a species of sunbird.[100] The Greeks wrote of a bird they called the Hēliodromos or "Sun-runner." It was believed to only live for a year and follow the sun. This species may have been the Indian Courser.[60]

Mammals

Varro spoke of three species of rabbits and hares. The Italian species, the white Gaulic species, and the Spanish species.[101] In ancient Greece in Rome rabbits had a sexual connotation and were associated with Aphrodite or Venus. Likely due to their high rates of reproduction.[102] Women would sacrifice hares to the gods in the hopes of improving their fertility. This animal was important to the goddesses Diana and Lucina.[103] Since meat was an expensive delicacy only available to the upper classes, animals such as rabbits were also only available as food to the wealthy.[104] The Romans may have lumped rats and mice into the same species.[105] They likely were a common occurrence in ancient Rome due to poor sanitation and difficulty eradicating rodents. Rats and mice likely arrived in Rome due to trade.[106] They may have caused plague outbreaks in Rome and Greece.[107] Bats were thought to have mythical properties. People would fasten bat heads to dovecotes to protect pigeons. Bat bodies could also serve as magic charms protecting sheepfolds and antidotes to snakebites.[108]

.jpg.webp)

Dogs and cats

Numerous animals were kept as pets in ancient Greece and Rome. Such as weasels, as they were seen as the ideal rodent killers, as well as dogs and cats. Aristotle believed that female cats are "naturally lecherous." The Greeks later syncretized the goddess Artemis with the Egyptian goddess Bastet, adopting Bastet's associations with cats and ascribing them to Artemis.[109][110] Dogs were associated with Hecate and were sacred to Ares and Artemis. Cerberus, Argos, and Laelaps were dogs in Greek mythology.[111] During the Battle of Marathon, one Athenian may have been accompanied by a dog. In the ancient world, dogs may have been used as guards and messengers for the military.[112] They were seen as protectors and guardians of their owners and their property.[113]

Elephants

Alexander the Great was influenced by Persian war elephants to utilize the species in battle.[114] The Macedonians would fight elephants by loosening their ranks to allow the elephants to pass through their ranks and then throw javelins at them. Through this tactic, they would pierce the legs of the unarmored elephants, thus scaring them into fleeing back to their armie's lines. The riders would be attacked by archers and javelins.[115][116] After his Indian campaign, Alexander created the position of elephantarch to lead his elephant units.[117] Polypercon, one of Alexander's generals made the first use of war elephants in Europe during his siege of Megalopolis. During the Punic Wars and the Pyrrhic War the Romans and their enemies used war elephants.[118] After the Punic Wars, the Romans brought back many elephants from Africa. The Romans used the North African elephant and the African bush elephant.[119]

Wolves

The ancient Greeks associated wolves with Apollo,[120] and the Romans associated wolves with Mars. In Roman mythology, the Capitoline Wolf nursed Romulus and Remus, sons of Mars and future founders of Rome. As a consequence, the she-wolf became a symbol of Rome and the Romans. It may have become an expression of loyalty to Rome and the emperor.[121] The Romans possibly refrained from harming or hunting wolves. "Lupus", the Roman word for wolf became a Roman cognomen. Plautus, a Roman comedian, used imagery of wolves to discuss the cruelty of men. An altar of Zeus was located at Mount Lykaion, a mountain in Arcadia. Lycaon, king of Arcadia, was said to sacrificed humans at this altar. Following this sacrifice, there would be a feast where one man would eat a portion of the sacrificed people. They would then be turned into a wolf.[122]

Lions

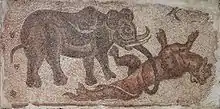

Lions were present in the Greek peninsula until classical times; the prestige of lion hunting was shown in Heracles' first labor, the killing of the Nemean lion,[123] and lions were depicted as prominent symbols of royalty, for example in the Lion Gate to the citadel of Mycenae.[124] Antiquity has examples where groups of dogs defeat the 'king of beasts,' the lion. Greek legend reflects Achilles' shield with the depiction of a fight of his dog against two lions. Early figurative Greek art places a strong emphasis on lions, especially Mycenaean art.[125] Cambyses II of the Achaemenid Empire possessed a dog that started a fight with two full-grown lions. Claudius Aelianus wrote that Indians showed Alexander the Great powerful dogs bred for lion-baiting.

Reptiles and amphibians

.jpg.webp)

Tortoiseshells may have been luxury goods imported from other parts of the world. They were often used to display the owner's wealth or to veneer furniture. Sometimes they would be dyed to increase their value or make them resemble a Tortoise shell may also have been used to make a type of instrument known as a chelys.[126] Different areas were thought to provide different tortoise shells. The best shells were said to come from the Malay Peninsula.[127] Tortoises inspired the testudo formation.[128] Lizards were symbols of death and rebirth as they were believed to go into hibernation.[129][130][131] The ancient Greeks and Romans had numerous cultural depictions of salamanders. Aristotle and Theophrastus both describe the salamanders as a sign of rain.[132] Nicander stated that the salamander could be used to make poison. While Theocritus may describe a way to use a salamander to make a love potion.[133] Aelian and Pliny the Elder also describe the salamander.[134][135]

Fungi

Edible mushrooms were highly valuable in ancient Rome and the poor were not capable of accessing them. Nero once called them the food of the gods.[136][137] The Romans knew of an edible mushroom now known as amanita caesarea, which translates to "Caesar's mushroom."[138] Galen termed mushrooms Bōlētus, which derived from the Ancient Greek word βωλιτης.[139] It was one of the most popular mushrooms in ancient Rome, especially Claudius.[140] Two other species the Romans knew of were Formitopsis officinalis and Boletus edulis. Boletus edulia was known as porcini, or little pigs.[141] Mushrooms were cooked in pots called boletariums.[142] As food, mushrooms would only be served on special or festive occasions.[137] The Greeks considered fungal diseases malevolent and edible funguses risky foods to eat due to cases of accidental poisoning.[143] Poisonous fungi were used for assassination in ancient Rome.[144][145] Pliny the Elder did not distinguish between mushroom species, instead calling them all agarikon.[141] Dioscorides believed that all funguses were made from decaying and damp earth, and were either inedible or had little nutritional value.[146] Agarikon, the Roman word for all mushrooms, was also the Greek word. Aristotle believed they were created by Zeus. Aristotle classified mushrooms as plants although he still believed that they might have belonged to their own class of living things.

Insects and snails

Butterflies were considered a symbol of the soul due to the many changes they went through in their lives. Butterfly wings were associated with magic and dreams. The goddess Psyche is usually depicted with butterfly wings.[147][148] Butterflies show up in art, architecture, and furniture throughout the Greco-Roman world.[149] There are numerous depictions of insects such as grasshoppers, ants, and scorpion flies in ancient Greece and Rome.[150] The Romans would create fibulae in the shape of cicada and flies. Grasshoppers were also used to decorate pottery and oil lamps. Alongside this, the Greeks and Romans were also beekeepers and had extensive knowledge of wasps and ants. Wasps were thought to build their nests by roads, which would attract children, who would disturb the wasp nests. Wasps were said to attack anyone who walked near the nests due to this. Ancient Roman beekeepers kept bee hives in the recesses in walls.[151] Other hives were organized horizontally and vertically. Only the combs with honey would be removed from the hives.[152] Hives could be made from a variety of materials. Such as terracotta, ferula, wood, cork, bark, and wicker.[153] Galen believed that bee venom could be used for pain relief.[154] Ants were thought to be capable of foretelling the future, including the weather. Cicadas were believed to have been men who were enthralled by the music of the Muses. They would keep singing until they died and the muses turned them into cicadas. This myth was likely linked to the belief the cicadas exclusively ate dew as the Muses would transform the singers into cicadas because they would capable of living without food or water.[155] Zeus was believed to have transformed ants into the Myrmidons and to have transformed a group of men who stole their neighbor's fruit into ants.[156] Snails would be bred in breeding pens known as cochlearia.[157] Triton shells were used by centaurs and gods in Greek mythology.[158]

In culture

Resources

In ancient Greece and Rome, the captive breeding of livestock, particularly the rearing of cattle, was an integral part of the economy. In both the Greek and Roman economies of antiquity, cattle were seen as a determiner of wealth, and herds often served as a dowry in certain arranged-marriage scenarios, as they still do today in many African and Central Asian cultures.[159] The works of Homer depict animal husbandry and livestock management as something practiced by the wealthy and powerful, with the larger herds generally belonging to respectable, higher-status men.[160] Cattle were versatile animals, as they are today, valued as beasts-of-burden as well as sources of milk, leather and meat.

Sheep and goats were also highly versatile animals. They served as sources of protein, but were mainly prized for their dairy products, including feta and goat cheese, as well as their wool. Sheep and goats were valued as natural “lawnmowers”, as well, being able to digest many weeds and perennials that are toxic or unpalatable to other hoofed animals. For example, in preparation for the sowing of vegetables or other crops, sheep and/or goats would help the farmers to clear a lot or field by eating all the unwanted, overgrown plant material. The animals would also be fertilizing the soil (with their droppings) in the process and aerating the soil with their hooves, thus preparing an area for planting.

Alongside sheep and cereal, other animals such as goats and pigs were crucial parts of ancient Greek cuisine.[113] Horses were considered a luxurious animal and a signifier of wealth and power.[160] Horses, mules, oxen, camels, and elephants were all used as working animals in ancient Rome and Greece.[113]

Entertainment

Venationes were some of the most popular public spectacles in ancient Rome. These performances involved the simulated “hunting” (and killing) of wild or exotic animals for public entertainment, usually within a stadium or colosseum. Outside of the colosseum setting, Roman legionaries likely played a part in capturing animals for these spectacles, with Julius Africanus recommending the task of animal capture as a form of military exercise. Some of the soldiers would earn exemption from other tasks or duties in return for successfully partaking in these hunts. These men became known as the venatores immunes. The hunters may likely have been assigned quotas of animals to hunt, by type, as well. Animals would be held in vivaria, which also may have served as a place of central organization for these hunts. Other groups were associated with hunting animals in ancient Rome. These included the vestigiatores and the ursarii. The vestigiatores were a group of animal trackers and the ursarii were bear-hunters.[161] Other forms of public entertainment involving animals in the classical world included theriotropheia and leporaria, which were further examples of animal pens, as well as the piscinae (early aquariums and fish ponds) and walk-through bird aviaries.

Larger animals would be displayed in cages, triumphs, or pens. Numerous dangerous and exotic species were captured for display—and likely eventual public slaughter—such as the Atlas bear, baboons, antelope (of numerous forms), the Barbary lion and leopard, wild and domestic buffalo, cheetahs, Caspian tigers, European bison (wizent), Aurochs, deer (of all types), giraffe, hippopotamus, Nile crocodiles, ostriches, black and white rhinoceroses, wild asses, zebras, in addition to various types of reptiles, including large monitors and pythons.[162] It was a popular sport and social “custom” to hit others in the head with quails, and men would walk around with quails under their coats in case a challenge appeared.[163] Love stories between different species are common in Classical literature.[164] They were usually seen as comical or scandalous by the people of the classical world.[165] Animals could be given as gifts, as they were a source of entertainment and proof of high social status.[166] People would make apes drunk for their own amusement, sometimes with disastrous consequences.[167] There may have once been a zoo or a similar garden, full of local and exotic animals in Alexandria, Egypt.[168]

Religious significance

Animals were seen as mediators between the gods and humans. Many gods took anthropomorphic forms and had close associations with animals. For example, Zeus turned into a swan and was associated with eagles. Numerous animals also appeared in Greco-Roman mythology. Such as the Hydra and the Chimera.[169] The ancient Greeks practices Ornithomancy and the Romans practiced Augury.[170] Which are the practices of foretelling omens through the movement of birds.[171] Animal sacrifice was a common religious practice throughout the classical world.[172]

In philosophy

Some Neopythagoreans, which was a school of Hellenistic philosophy, practiced vegetarianism and believed that animals should be protected.[173][174][175] Plutarch and Porphyry also believed in vegetarianism, and Plutarch believed that animals were more virtuous than humans.[176] Porphyry believed that animal sacrifice was inefficient as the gods did not want dead animals. He also argued against hurting animals or using them for labor.[177] In Roman art, animals were typically depicted as subservient to humans. Many ancient Roman sarcophagi depict the deceased hunting animals and therefore their bravery.[178] Philosophers debated the differences between animals and humans. [179] According to Aristotle humans are separate from animals as they have the capacity for reason and are meant to achieve their best.[180][181] Philosophers such as Plutarch placed animals in human situations to better convey the positives and negatives of human nature.[182] Plutarch believed that animals were of higher moral virtue because they could not act against their moral nature, while humans can.[183] The Stoics believed that animals naturally achieved the stoic way of life.[184] Ancient writers had a concept of “animal envy” which is the idea that animals were envious of human skills.[179] Augustine, a Christian theologian believed that animals were not part of the City of God as they were irrational beings.

Relationships

In the ancient world, people could have strong emotional connections to animals. People made personal connections with their cattle and other work animals.[185] People would also form deep connections with their horses. For example, Alexander the Great had a close bond with his horse Bucephalus. Emperor Hadrian once said: “My horse knew me not by the thousand approximate notions of title, function, and name which complicate human friendship, but solely by my just weight as a man. He shared my every impetus; he knew perfectly, and perhaps better than I, the point where my strength faltered under my will.”[186][187] Aristocrats likely had a less personal relationship with their horses. Wealthy Greeks likely would replace horses for the sake of novelty. This would demonstrate wealth as horses were expensive and it required a high level of wealth and prestige to afford to consistently replace them.[188] People kept pets in Classical antiquity. Arrian describes his relationship with his dog Horme in his writings.[189] Arrian also describes humans trying to keep their dogs with chronic medical conditions.[190] According to Plato, dogs are valuable pets as they provide unconditional love and affection. Plutarch wrote that humans with difficult relationships with other people often find themselves close to dogs.[191] People would sometimes build graves for their pets. One such burial is located behind the Stoa of Attalus in Athens.[192] The ancient Greeks had unique animal naming conventions. Pets would sometimes be given names, but only those which could not be given to a human. Indicating that they were not seen as equals.[193] Dogs were seen as a positive reflection of the owner’s masculinity and bravery.[194] Birds were valuable pets in the ancient world. Talking birds were seen as useful for entertainment and attracting attention.[195] Birds were popular pets among women and often played with children.[196]

References

- Ross 2007, p. 10.

- Guilas & Oliver 2014, p. 254.

- Lovano 2019, p. 138.

- Sutton 2017.

- Stewart et al. 2005, p. 35.

- Klar 2015, p. 30.

- Boyett, Tarver & Gleason 2020, p. 200.

- Helstosky 2009, p. 53.

- Yamauchi & Wilson 2022.

- Irby 2016, p. 608.

- Hynson 2008, p. 18.

- Mouritsen & Styrbæk 2021, p. 116.

- Adolf 2019, p. 87.

- Miyake, Miyabe & Nakano 2004, p. 19.

- Longo, Clausen & Clark 2015.

- Lado 2016, p. 3.

- Henderson 2007, p. 166.

- Irby 2016, p. 865.

- Michell 1963, p. 136.

- Gilbey 2011, p. 20-21.

- Hopkins 2007, p. 6.

- Albala 2015, p. 512.

- Stransbury-O'Donnell 2019, p. 704.

- Gargarin 2010, p. 1.

- Ashworth 2006, p. 12.

- Lytle 2006, p. 42.

- Lytle 2006, p. 43.

- Corbishley 2004, p. 74-75.

- Kazhdan 2005.

- Michell 1963, p. 286-290.

- Matz 2019, p. 169-170.

- Sfetcu 2014, p. 40.

- Wilson 2013, p. 291.

- Lovano 2019, p. 141.

- Radcliffe 1926, p. 117.

- Radcliffe 1926, p. 122.

- Lovano 2019, p. 142.

- Bartley 2003, p. 38.

- Stambaugh 1988, p. 148.

- Bonner 2022, p. 138.

- Ambrose et al. 2020.

- Reiss 2011, p. 36-39.

- Gibson & Atkinson 2003, p. 355.

- Siebert 2011, p. 25.

- King 2012, p. 58.

- Spanier 2015, p. 227.

- Spanier 2015, p. 227-228.

- Spanier 2015, p. 228.

- Spanier 2015, p. 229.

- Muhammad, Zia & Zuber 2017, p. 155.

- O'Connor 2017, p. 51-52.

- Sangeetha & Thangadurai 2022.

- Pereira & Cotas 2019, p. 1-22.

- Buschmann et al. 2017, pp. 391–406.

- Widrig, Scott & 2020.

- Kim 2015, p. 127.

- Dalby 2013, p. 342.

- Curtis 1984, p. 430-445.

- Laist 2017, p. 47.

- Arnott 2007, p. 98.

- Bober 2000, p. 47.

- Yalden & Albarella 2009, p. 102.

- Coren 2018, p. 152.

- Dalby 2013, p. 124.

- Arnott 2007, pp. 237–238.

- Heinrichs 2014, p. 54.

- Arnott 2007, p. 47-48.

- Arnott 2007, p. 114.

- Arnott 2007, p. 119.

- Arnott 2007, pp. 208–209.

- Arnott 2007, p. 9.

- Arnott 2007, p. 8.

- Arnott 2007, pp. 40–41.

- Arnott 2007, p. 156.

- Arnott 2007, p. 165.

- Arnott 2007, p. 32.

- Arnott 2007, p. 134.

- Arnott 2007, p. 141.

- Arnott 2007, p. 2-3.

- Arnott 2007, p. 10.

- Arnott 2007, p. 83.

- Netzley 2009, p. 189.

- Duncan 2003, p. 94.

- Arnott 2007, p. 84.

- Soni 2022.

- Arnott 2007, p. 43-44.

- Arnott 2007, pp. 28–29.

- Arnott 2007, pp. 17–19.

- Lembke 2012.

- Arnott 2007, p. 49-50.

- Arnott 2007, pp. 182–184.

- Lynch & Rocconi 2020, p. 30.

- Arnott 2007, p. 12-13.

- Arnott 2007, p. 59-60.

- Arnott 2007, p. 46.

- Arnott 2007, pp. 80–82.

- Arnott 2007, pp. 246–247.

- Warhol & Schneck 2010, p. 194.

- Arnott 2007, p. 7.

- Arnott 2007, p. 372.

- Irby 2016.

- Beeler & Beeler 2022, p. 128.

- Davis & DeMello 2003, p. 175.

- Wyse 2022.

- Sallares 1991, p. 263.

- Erdkamp 2013, p. 121.

- Hovell 2013.

- Arnott 2007.

- Engels 2001, pp. 48–87.

- Rogers 2006.

- Sherman 2008, pp. 118–121.

- Forster 1941, p. 115-117.

- Thommen 2012, p. 45.

- Alexandrius 1899.

- Davis & DeMello 2003, p. 51.

- Chinnock 2016.

- Nossov 2008, p. 19.

- Appian, p. 46-47.

- Thomas 2004, pp. 189–191.

- Mech & Boitani 2010, p. 292.

- Rissanen 2014.

- Mahoney, p. la.812.

- Graves 1955, p. 465-469.

- Gates 2003, p. 136-137.

- Thomas 2004, p. 189-191.

- Schlesinger 1911, p. 26.

- Pederson 2021, pp. 71–73.

- Simkin 1997.

- Impelluso 2004, p. 276.

- Gauding 2009, p. 268.

- Kaster 2005, p. 1050.

- Theophrastus & Hort 1916, p. 400.

- Wallace 2018, p. 44.

- White 1992, pp. 183–184.

- Aelian 1958, p. Bk. 2, Sec. 30.

- Cumo 2015, p. 223.

- Sassine 2021, p. 2.

- Money 2022, p. 131.

- Laessøe 1953, p. 6.

- Marley 2010, p. 112.

- Lawrence 2022, p. 12.

- Faas 2005, p. 74.

- Lawrence 2022, p. 10.

- Lapico 2015.

- Parker 2009, p. 31.

- Lawrence 2022, p. 12-13.

- Gere 2011, p. 135.

- Sax 2001, p. 52.

- Laufer 2010, p. 183.

- Kritsky & Smith 2018, p. 875-876.

- Kritsky 2010, p. 52.

- Chen et al. 2021, p. 21.

- Kristensen 2007, p. 3.

- Chen et al. 2021, p. 159.

- Fossheim, Songe-Møller & Ågotnes 2019, pp. 148–149.

- Euripides 2012, p. 48.

- Kershaw 2012, p. 174.

- Garlough & Campbell 2012, p. 396.

- Lonsdale 1979, p. 147.

- Migeotte 1984.

- Epplett 2001, pp. 210–222.

- Thommen 2012, p. 95-97.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 77.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, pp. 35–44.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, pp. 46–47.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 70.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 78.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, pp. 343.

- Thommen 2012, p. 46-48.

- Ogden 2010, p. 151.

- Aeschylus 1982.

- Jameson 2015, p. 198-231.

- Hadot 2002, p. 190.

- Jáuregui 2010, p. 350.

- Bowersock 1999, p. 70.

- Nussbaum 2019, p. 237.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 142.

- Thommen 2012, p. 97.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 4.

- Aristotle.

- Newman 1987, pp. 189–190.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 11.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 237-238.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 239.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, pp. 24–25.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 2.

- Yourcenar 2005, p. 7.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, pp. 28–30.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 31.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 32.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 64.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, pp. 64–65.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 65.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 67.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 69.

- Fögen & Thorsten 2017, p. 70-71.

Bibliography

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, vol. 1, archived from the original on July 21, 2022

- Aeschylus (1982), Prometheus Bound

- Alexandrius, Appianus (1899). The Syrian Wars, IV, 16–20. Translated by White, Horace.

- Appian. Roman History, Book 6, The wars in Spain. pp. 46–47.

- Aelian (1958). Scholfield, A.F. (ed.). De Natura Animalium. Loeb. p. Bk. 2, Sec. 30. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- Adolf, Steven (November 9, 2019), Tuna Wars: Powers Around the Fish We Love to Conserve, Springer International Publishing, ISBN 978-303-020-641-3

- Ashworth, Leon (2006), Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Greece, Cherytree, ISBN 978-184-234-268-8

- Albala, Ken (March 27, 2015), "Fishing For Sports", The SAGE Encyclopedia of Food Issues, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-150-631-730-4

- Ambrose, Jamie; Beer, Amy-Jane; Harvey, Derek; Dipper, Francis; Ripley, Esther; Stow, Dorrik (2020-09-29). Oceanology: The Secrets of the Sea Revealed. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7440-3650-3.

- Arnott, W. Geoffrey (2007), Birds in the Ancient World From A to Z (PDF), Oxfordshire: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-94662-6, archived from the original (PDF) on August 4, 2022, retrieved September 19, 2022

- Buschmann, Alejandro H.; Camus, Carolina; Infante, Javier; Neori, Amir; Israel, Álvaro; Hernández-González, María C.; Pereda, Sandra V.; Gomez-Pinchetti, Juan Luis; Golberg, Alexander; Tadmor-Shalev, Niva; Critchley, Alan T. (2 October 2017). "Seaweed production: overview of the global state of exploitation, farming and emerging research activity". European Journal of Phycology. 52 (4): 391–406. doi:10.1080/09670262.2017.1365175. S2CID 53640917.

- Bartley, Adam Nicholas (2003). Stories from the Mountains, Stories from the Sea: The Digressions and Similes of Oppian's Halieutica and the Cynegetica. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-25249-9.

- Beeler, Karin; Beeler, Stan (2022-10-15). Animals in Narrative Film and Television: Strange and Familiar Creatures. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-6669-0482-6.

- Bowersock, Glen Warren (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-51173-6.

- Bonner, Stanley F. (2022-09-23). Education in Ancient Rome: From the Elder Cato to the Younger Pliny. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-34775-5.

- Bober, Phyllis Pray (2000). Art, Culture, and Cuisine: Ancient and Medieval Gastronomy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06254-9.

- Boyett, Colleen; Tarver, H. Micheal; Gleason, Mildred Diane (2020-12-07). Daily Life of Women: An Encyclopedia from Ancient Times to the Present [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-4693-9.

- Corbishley, Mike (2004), Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, J. Paul Getty Museum, ISBN 978-089-236-705-4

- Cumo, Christopher (2015-06-30). Foods that Changed History: How Foods Shaped Civilization from the Ancient World to the Present: How Foods Shaped Civilization from the Ancient World to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3537-7.

- Coren, Giles (2018-05-01). The Story of Food: An Illustrated History of Everything We Eat. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-4654-9478-8.

- Chen, C.; Fang, Y; Colonna, A.; Fontana, P.; Lloyd, D.J.; Martinez, L.; Mukomana, D.; Roberts, J.M.L; Schrouten, C.N. (2021-09-21). Good beekeeping practices for sustainable apiculture. Food & Agriculture Org. pp. 21, 159. ISBN 978-92-5-134612-9.

- Chinnock, E.J. (2016-10-23). "The Anabasis of Alexander; or, The history of the wars and conquests of Alexander the Great. Literally translated, with a commentary, from the Greek of Arrian, the Nicomedian". Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- Curtis, Robert (1984), "Salted Fish Products in Ancient Medicine", Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 39 (4): 430–445, doi:10.1093/jhmas/39.4.430, PMID 6389686, retrieved 2022-09-12

- Dalby, Andrew (2013-04-15). Food in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-95422-2.

- Duncan, James R. (2003). Owls of the World: Their Lives, Behavior and Survival. Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55297-845-0.

- Davis, Susan E.; DeMello, Margo (2003). Stories Rabbits Tell: A Natural and Cultural History of a Misunderstood Creature. Lantern Books. ISBN 978-1-59056-044-0.

- Erdkamp, Paul (2013-09-05). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Rome. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89629-0.

- Euripides (2012-05-17). Euripides: Iphigeneia at Aulis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60116-1.

- Epplett, Christopher (2001). "The Capture of Animals by the Roman Military". Greece & Rome. 48 (2): 210–222. doi:10.1093/gr/48.2.210. ISSN 0017-3835. JSTOR 826921.

- Engels, D. W. (2001) [1999]. "Greece". Classical Cats: The Rise and Fall of the Sacred Cat. London: Routledge. pp. 48–87. ISBN 978-0-415-26162-3.

- Faas, Patrick (2005). Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-23347-5.

- Fossheim, Hallvard; Songe-Møller, Vigdis; Ågotnes, Knut (2019-08-22). Philosophy as Drama: Plato's Thinking through Dialogue. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-08250-2.

- Fögen, Thomas; Thorsten, Edmund (2017). Interactions between Animals and Humans in Graeco-Roman antiquity. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110545623-001. ISBN 978-0-226-23347-5.

- Forster, E. S. (1941). "Dogs in Ancient Warfare". Greece & Rome. 10 (30): 115–117. doi:10.1017/S0017383500007427. ISSN 0017-3835. JSTOR 641375. S2CID 162546398.

- Gargarin, Michael (2010), Riddles, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-019-517-072-6

- Gates, Charles (2003). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece, and Rome. New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12182-5.

- Gere, Cathy (2011-06-01). The Tomb of Agamemnon. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06824-7.

- Graves, R (1955). "The First Labour:The Nemean Lion". Greek Myths. London: Penguin. pp. 465–469. ISBN 0-14-001026-2.

- Garlough, Robert B.; Campbell, Angus (2012-11-16). Modern Garde Manger: A Global Perspective. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-133-71511-5.

- Gauding, Madonna (2009). The Signs and Symbols Bible: The Definitive Guide to Mysterious Markings. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4027-7004-3.

- Gibson, R. N.; Atkinson, R. J. A. (2003-07-31). Oceanography and Marine Biology, An Annual Review, Volume 41: An Annual Review: Volume 41. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-18057-0.

- Guilas, Bernard; Oliver, Ronald (November 7, 2014), Two Chefs, One Catch: A Culinary Exploration of Seafood, Lyons Press (published November 7, 2014), ISBN 978-149-301-633-4

- Gilbey, Henry (May 2, 2011), The Complete Fishing Manual, DK Publishing, ISBN 978-075-668-527-0

- Marley, Greg A. (2010). Chanterelle dreams, amanita nightmares : the love, lore, and mystique of mushrooms. White River Junction, Vt.: Chelsea Green Pub. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-60358-214-8.

- Heinrichs, Christine (2014-01-15). How to Raise Poultry: Everything You Need to Know, Updated & Revised. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-4567-2.

- Helstosky, Carol (2009), Food Culture in the Mediterranean, Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-031-334-626-2

- Henderson, W.J. (January 1, 2007), Food in the Ancient World, John M. Wilkins & Shaun Hill : book review, Acta Classica: Proceedings of the Classical Association of South Africa, vol. 50, Classical Association of South Africa

- Hopkins, Ellen (2007), Freshwater Fishing, Capstone Press, ISBN 978-142-960-820-6

- Hadot, Pierre (2002). What is Ancient Philosophy?. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01373-5.

- Hovell, Mark (2013-04-18). Rats and How to Destroy Them (Traps and Trapping Series - Vermin & Pest Control). Read Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4474-9937-4.

- Hynson, Colin (July 15, 2008), How People Lived in Ancient Greece, PowerKids Press, ISBN 978-143-582-621-2

- Irby, Georgia L. (2016-01-19). A Companion to Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Greece and Rome. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-37297-5.

- Impelluso, Lucia (2004). Nature and Its Symbols. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-772-6.

- Jameson, Michael H. (2015), "Sacrifice and Animal Husbandry in Ancient Greece", Cults and Rites in Ancient Greece: Essays on Religion and Society, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 198–231, ISBN 978-0-521-66129-4

- Jáuregui, Miguel Herrero de (2010-03-26). Orphism and Christianity in Late Antiquity. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-021660-8.

- Stambaugh, John (1988). The Ancient Roman City. JHU Press. p. 148.

- Kim, Se-Kwon (2015-04-30). Handbook of Marine Microalgae: Biotechnology Advances. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-801124-9.

- Kaster, Robert (2005-07-21). Emotion, Restraint, and Community in Ancient Rome. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-028636-1.

- King, Richard J. (2012-01-01). Lobster. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-994-1.

- Kazhdan, Alexander (2005), "Taranto", The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-019-504-652-6

- Kritsky, Gene; Smith, Jessee J. (2018-05-23), "Insect Biodiversity in Culture and Art", Insect Biodiversity, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 869–898, doi:10.1002/9781118945582.ch29, ISBN 978-1-118-94558-2, retrieved 2022-09-16

- Kritsky, Gene (2010-02-24). The Quest for the Perfect Hive: A History of Innovation in Bee Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-19-974238-7.

- Klar, Jeremy (2015-12-15). The Totally Gross History of Ancient Rome. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4994-3747-8.

- Kershaw, Diana R. (2012-12-06). Animal Diversity. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-011-6035-3.

- Lado, Ernesto (February 4, 2016), The Common Fisheries Policy: The Quest for Sustainability, Wiley (published February 4, 2016), ISBN 978-111-908-566-9

- Lembke, Janet (2012-11-01). Chickens: Their Natural and Unnatural Histories. Skyhorse + ORM. ISBN 978-1-5107-2015-2.

- Laist, David W. (2017-03-29). North Atlantic Right Whales: From Hunted Leviathan to Conservation Icon. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-2099-8.

- Lapico, Marisa (2015-09-09). HEALING FUNGI - The Way of Wellness. Edizioni Il Fiorino Modena. ISBN 978-88-7549-571-8.

- Lovano, Michael (2019-12-02). The World of Ancient Greece: A Daily Life Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3731-9.

- Laufer, Peter (2010-05-04). Dangerous World of Butterflies: The Startling Subculture of Criminals, Collectors, and Conservationists. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7627-9981-7.

- Lawrence, Sandra (2022-08-09). The Magic of Mushrooms: Fungi in folklore, superstition and traditional medicine (in Arabic). Welbeck Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-80279-448-9.

- Longo, Stefano B.; Clausen, Rebecca; Clark, Brett (2015-06-25). The Tragedy of the Commodity: Oceans, Fisheries, and Aquaculture. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-7563-6.

- Lynch, Tosca A. C.; Rocconi, Eleonora (2020-06-29). A Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Music. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-27549-7.

- Lytle, Ephraim (February 3, 2006), Marine Fisheries and the Ancient Greek Economy (PDF), Duke University

- Lonsdale, Steven H. (1979). "Attitudes towards Animals in Ancient Greece". Greece & Rome. 26 (2): 146–159. doi:10.1017/S0017383500026887. ISSN 0017-3835. JSTOR 642507. S2CID 162739658.

- Matz, David (October 31, 2019), Ancient Roman Sports, A-Z: Athletes, Venues, Events and Terms, McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers (published October 31, 2019), ISBN 978-147-663-624-5

- Miyake, Makoto; Miyabe, Naozumi; Nakano, Hideki (2004), Historical Trends of Tuna Catches in the World, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, ISBN 9789251051368

- Mouritsen, Ole G.; Styrbæk, Klavs (2021-05-06). Octopuses, Squid & Cuttlefish: Seafood for Today and for the Future. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-58027-8.

- Kristensen, Kurt (July 21, 2007). Beekeeping in Roman Age: Economy, production, symbolism.O'Connor, Kaori (2017-05-15). Seaweed: A Global History. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-799-2.

- Ogden, D. (2010), A Companion to Greek Religion

- Pereira, Leonel; Cotas, João (2019). "Historical Use of Seaweed as an Agricultural Fertilizer in the European Atlantic Area". Seaweeds as Plant Fertilizer, Agricultural Biostimulants and Animal Fodder. pp. 1–22. doi:10.1201/9780429487156-1. ISBN 978-0-429-48715-6. S2CID 213435775.

- Pederson, Maggie Campbell (2021-04-26). Tortoiseshell. The Crowood Press. ISBN 978-0-7198-3145-4.

- Parker, Steve (2009). Molds, Mushrooms & Other Fungi. Capstone. ISBN 978-0-7565-4223-8.

- Ross, Stewart (2007), Ancient Greece Entertainment, Compass Point Books, ISBN 978-075-652-086-1

- Reiss, Diana (2011). The Dolphin in the Mirror: Exploring Dolphin Minds and Saving Dolphin Lives. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-547-44572-4.

- Rissanen, Mika (2014). "The Lupa Romana in the Roman Provinces". Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Akadémiai Kiadó. 65 (2): 335–360. doi:10.1556/AArch.65.2014.2.4.

- Laessøe, Thomas (1953). Mushrooms & Toadstools. Collins. p. 6. ISBN 1-870630-09-2.

- Radcliffe, William (1926). Fishing from the earliest times. London: J. Murray.

- Rogers, K. M. (2006). "Wildcat to Domestic Mousecatcher". Cat. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 7–48. ISBN 978-1-86189-292-8. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020.

- Sax, Boria (2001). The Mythical Zoo: An Encyclopedia of Animals in World Myth, Legend, and Literature. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-612-5.

- Sangeetha, Jeyabalan; Thangadurai, Devarajan (2022-10-06). Seaweed Biotechnology: Biodiversity and Biotechnology of Seaweeds and Their Applications. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-000-60898-4.

- Sherman, Josepha (2008). Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore. Sharpe Reference. pp. 118–121. ISBN 978-0-7656-8047-1.

- Sutton, David (November 21, 2017), Rich Food, Poor Food, Chapelfields Press, ISBN 9781843964810

- Mahoney, Anne, Suda Encyclopedia, archived from the original on September 13, 2022, retrieved September 17, 2022

- Simkin, John (1997). "Military Tactics of the Roman Army". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- Sassine, Youssef Najib (2021-10-06). Mushrooms: Agaricus bisporus. CABI. ISBN 978-1-80062-041-4.

- Stransbury-O'Donnell, Mark (2019), "Daily Life in Ancient Greece at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston", American Journal of Archaeology, 123 (4): 699–705, doi:10.3764/aja.123.4.0699, S2CID 204723963

- Soni, Hiren B. (2022-06-13). Owl 'The Mysterious Bird'. Pencil. ISBN 978-93-5610-605-5.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). "Chelys". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 26.

- Stewart, David; Antram, David; Bergin, Mark; James, John (2005). Inside Ancient Rome. Enchanted Lion Books. ISBN 978-1-59270-045-5.

- Sallares, Robert (1991). The Ecology of the Ancient Greek World. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-2615-5.

- Siebert, Charles (2011-04-20). NRDC The Secret World of Whales. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-0574-1.

- Sfetcu, Nicolae (2014-05-03). Fish & Fishing. Nicolae Sfetcu.

- Spanier, Ehud (2015), The Utilization of Lobsters by Humans in the Mediterranean Basin from the Prehistoric Era to the Modern Era – An Interdisciplinary Short Review (PDF), vol. 1, Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies

- Theophrastus; Hort, Arthur Fenton (1916). Enquiry into plants : and minor works on odours and weather signs. London: Heinemann. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.162657.

- Thommen, Lukas (2012), An Environmental History of Ancient Greece and Rome, translated by Hill, Phillip, Universität Basel, Switzerland: Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511843761, ISBN 978-051-184-376-1, archived from the original on May 31, 2022

- Wallace, Ella Faye (2018). The Sorcerer's Pharmacy. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers (Doctoral Dissertation). p. 44.

- White, T.H. (1992) [1954]. The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation From a Latin Bestiary of the Twelfth Century. Stroud: Alan Sutton. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-7509-0206-9.

- Widrig, Taylor; Scott, Briana Corr (2020-07-06). The Mermaid Handbook: A Guide to the Mermaid Way of Life, Including Recipes, Folklore, and More. Nimbus+ORM. ISBN 978-1-77108-866-4.

- Wilson, Nigel (2013-10-31). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-78799-7.

- Wyse, Elizabeth (2022-10-01). A History of the Classical World: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome. Arcturus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-3988-2428-7.

- Warhol, Tom; Schneck, Marcus (2010-10-01). Birdwatcher's Daily Companion: 365 Days of Advice, Insight, and Information for Enthusiastic Birders. Quarry Books. ISBN 978-1-61059-399-1.

- Yamauchi, Edwin; Wilson, Marvin (May 17, 2022), Dictionary of Daily Life in Biblical & Post-Biblical Antiquity: Food Consumption, Hendrickson Publishers, ISBN 978-161-970-794-8

- Yalden, Derek; Albarella, Umberto (2009). The History of British Birds. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-921751-9.

- Yourcenar, Marguerite (2005-05-18). Memoirs of Hadrian. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-374-52926-0.

- Muhammad, Ali; Zia, Khalid; Zuber, Mohammad (June 19, 2017), Algae Based Polymers, Blends, and Composites: Chemistry, Biotechnology and Materials Science, Elsevier Publishing, ISBN 978-012-812-361-4

- Mech, L. David; Boitani, Luigi (2010-10-01). Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-51698-1.

- Money, Nicholas P. (2022-10-24). Mushrooms: A Natural and Cultural History. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-791-6.

- Migeotte, Léopold (1984), "L'emprunt public dans les cités grecques", Recueil des documents et analyse critique, Québec-Paris: éditions du Sphinx et Belles Lettres, ISBN 2-7298-0849-3

- Michell, Humfrey (1963). The Economics of Ancient Greece. CUP Archive.

- Netzley, Patricia D. (2009-06-25). Witchcraft. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-0-7377-4638-9.

- Nossov, Konstantin (2008). War Elephants. ISBN 978-1-84603-268-4.

- Newman, W.L. (1987), The Politics of Aristotle: With an Introduction, Two Prefatory Essays and Notes Critical and Explanatory, pp. 189–190, ISBN 9781108011150

- Nussbaum, Martha C. (2019-08-13). The Cosmopolitan Tradition: A Noble but Flawed Ideal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-24298-2.

- Thomas, Nancy (2004). "The Early Mycenaean Lion up to Date". Charis: Essays in Honor of Sara A. Immerwahr. Princeton: Hesperia. pp. 189–191. ISBN 0876615337.