Animals in Meitei culture

Animals (Meitei: Saa/Shaa) have significant roles in different elements of Meitei culture, including but not limited to Meitei cuisine, Meitei dances, Meitei festivals, Meitei folklore, Meitei folktales, Meitei literature, Meitei mythology, Meitei religion, etc.

_(4489839164).jpg.webp)

Deer in Meitei culture

In one of the epic cycles of incarnations in Moirang, Kadeng Thangjahanba hunted and brought a lovely Sangai deer alive from a hunting ground called "Torbung Lamjao" as a gift of love for his girlfriend, Lady Tonu Laijinglembi. However, when he heard the news that his sweetheart lady married King Laijing Ningthou Punsiba of ancient Moirang, during his absence, he got extremely disappointed and sad. And so, with the painful and sad feelings, he realised and sensed the feelings of the deer for getting separated from its mate (partner). So, he released the deer in the wild of the Keibul Lamjao (modern day Keibul Lamjao National Park regions). Since then, the Sangai species started living in the Keibul Lamjao region as their natural habitat.[1][2]

Dogs in Meitei culture

Dogs are mentioned as friends or companions of human beings, in many ancient tales and texts. In many cases, when dogs died, they were given respect by performing elaborate death ceremonies, equal to that of human beings.[3]

When goddess Konthoujam Tampha Lairembi saw smokes in her native place, she was restless. She came down to earth from heaven to find out who was dead. On reaching the place, her mother told her as follows:

"O daughter of mine, none of your parents or brothers ever dies. The watchful dog of your Lord Soraren kept amidst us was fatally bitten by a snake. Only we performed its last rites."

— Konthoucham Nongkalol (Konthoujam Nonggarol)[3]

Elephants in Meitei culture

In the Meitei epic of the Khamba and Thoibi, the crown prince Chingkhu Akhuba of ancient Moirang and Kongyamba, planned to kill to Khuman Khamba.[4] Kongyamba and his accomplices together threatened Khamba to give up Moirang Thoibi, which Khamba rejected. Then they fought, and Khamba bet all of them, and was about to kill Kongyamba, but the men that stood by, the friends of Kongyamba, dragged Khamba off, and bound him to the elephant of the crown prince, with ropes. Then they goaded the elephant, but the God Thangching stayed it so that it didn't move. Finally, Kongyamba lost patience. He pricked a spear to the elephant so that it moved in the pain. But it still didn't harm Khamba. Khamba seemed to be dead. Meanwhile, on the other hand, Goddess Panthoibi came in a dream to Thoibi and told her everything that was happening. So, Thoibi rushed to the spot and saved Khamba from the elephant torture.[5]

Fishes in Meitei culture

Horses in Meitei culture

Lions in Meitei culture

Kanglā Shā

In Meitei mythology and religion, Kangla Sa (Meitei for 'Beast of the Kangla'), also spelled as Kangla Sha, is a guardian dragon lion, whose appearance is described as a creature with a lion's body and a dragon's head, and two horns. Besides being sacred to the Meitei cultural heritage,[6][7] it is frequently portrayed in the royal symbol of the Meitei royalties (Ningthouja dynasty).[8] The most popular iconographic colossal statues of the "Kangla Sa" stand inside the Kangla Fort in Imphal.[9]

In Meitei traditional race competitions, winners of the race are declared only after symbolically touching the statue of the dragon "Kangla Sha". This ideology is clearly mentioned in the story of the marathon competition between Khuman Khamba and Nongban in the epic saga of Khamba and Thoibi of ancient Moirang.[10]

Nongshāba

In Meitei religion (Sanamahism) and mythology, Nongshaba, also spelled as Nongsaba[lower-alpha 1] (Meitei: ꯅꯣꯡꯁꯥꯕ), is a Lion God and a king of the gods.[11][12][13] He produced light in the primordial universe and is often addressed as the "maker of the sun".[14][15][16][17] He is worshipped by the Meitei people, specifically by those of the Ningthouja clans as well as the Moirang clans. He was worshipped by the Meitei people of Moirang clan as an ancestral lineage God.[18][19][20][21] He is the chief of all the Umang Lais (Meitei for 'forest gods') in Ancient Kangleipak (early Manipur).[22][19][23][20]

Monkeys in Meitei culture

The Meitei folktale of Hanuba Hanubi Paan Thaaba (Meitei for 'Old Man and Old Woman planting Colocasia/Taro'), also known as the Hanubi Hentak! Hanuba Hentak!, is about the story of an old man and an old woman who were deceived by a group of trickster monkeys.[24][25][26]

In the story, a childless old couple used to treat a group of monkeys, from the nearby forest, kindly like their own children. Once the old couple were advised by the group of monkeys about planting taro plants (Meitei: ꯄꯥꯟ/ꯄꯥꯜ, romanized: "paan"/"paal") in their kitchen garden.[27][28][29] The couple believed them in good faith. So, according to their suggestion, they peeled off tubers of the taros, then boiled them in a pot until softened, then cooled them, then wrapped them in the banana leaves tightly, and finally planted them in the soil, by burying them.[30][31] In the midnight, the monkeys secretly steal and ate all the cooked taros from the garden, and planted some inedible giant wild taros, uprooted from somewhere. On the next day, the old couple found the fully grown taros they had planted the previous day. The two immediately cooked those full-grown taros and ate them. But as a reaction of the wild plants, the couple suffered from allergy. It was only after they ate the hentak medicine that their allergy was cured.[32][33][34] Realising the tricks of the monkey, the old couple planned to take revenge. So, the old man (Meitei: ꯍꯅꯨꯕ, romanized: "hanuba") acted to be dead, and the old woman (Meitei: ꯍꯅꯨꯕꯤ, romanized: "hanubi") acted to be crying out loudly to make the monkeys hear her sounds. When the monkeys came and asked her what had happened, she told them that the old man died after eating the taros.[34] She asked them to help her taking the old man's body out in the lawn. All the monkeys came inside the house. As soon as they came near him, he took up his stick and bet them. Frightened, they all ran away. The old couple knew that the monkeys would surely come back.[35][36][37] So, the couple climbed up on the attic of the house and hid there. When the monkeys came back with a larger gang to take revenge, the attic broke and felt upon them. Thus, they fled from the spot. Knowing that they might come back again, the old couple hid inside a large pot. When the monkeys came back with their gangs, the couple farted one by one continuously and finally, the pot where they were hiding banged on unexpectedly. The loud sound of the breaking scared the monkeys who fled from the spot and never came back again.[38][39]

Pythons in Meitei culture

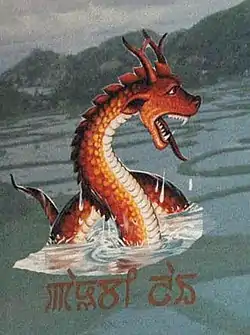

In Meitei mythology and folklore, Poubi Lai (Meitei: ꯄꯧꯕꯤ ꯂꯥꯏ), also known as Paubi Lai (Meitei: ꯄꯥꯎꯕꯤ ꯂꯥꯏ), was an ancient Meitei dragon python. It used to live in the deep waters of the Loktak Lake of Kangleipak.[40][41][42] It is also referred to as "Loch Ness Monster of Manipur".[43]

Rodents in Meitei culture

In Meitei mythology and religion, Shapi Leima (Meitei: ꯁꯄꯤ ꯂꯩꯃ), also known as Shabi Leima (Meitei: ꯁꯕꯤ ꯂꯩꯃ), is a goddess associated with the rodents. She is the mistress and the queen of all the rodents living in the entire world. She is one of the three favorite daughters of the sky god. Along with her two sisters, Khunu Leima and Nganu Leima, she married the same man.[44]

Tigers in Meitei culture

Tigers are among the most mentioned animals in different elements of Meitei culture.

Keibu Keioiba

In the Meitei mythology and folklore, Keibu Keioiba (Meitei: ꯀꯩꯕꯨ ꯀꯩꯑꯣꯏꯕ), also known as Kabui Keioiba (Meitei: ꯀꯕꯨꯏ ꯀꯩꯑꯣꯏꯕ), is a mythical creature with the head of a tiger and the body of a human. He is often described as half man and half tiger.[45][46][47][48] He was once a skilful priest named Kabui Salang Maiba. With his witchcraft, he transfigured himself into the form of a ferocious tiger. As a punishment of his pride (divine retribution), he could not completely turn back to his original human form.[47][45]

Khoirentak tiger

In the Meitei folktale of the Khamba and Thoibi, Khuman Khamba and Nongban were in conflict regarding the affairs of princess Moirang Thoibi. Both men wanted to marry the princess. Among the two suitors, the princess had already chosen Khamba but still Nongban did not give up easily. The matter was set before the King of ancient Moirang in his court, and he ordered them to settle the matter by the trial by ordeal of the spear. However, an old woman said that there was a tiger in the forest hardby that attacked the people. So, the King chose the tiger hunt to be the witness and the ordeal. Whoever among the two that killed the tiger will get the Princess Thoibi as his wife. On the next day, the King and his ministers gathered there in stages. Many people gathered at the spot, that it seemed like a white cloth spread on the ground. Then the two went inside the forest. Near a dead body of a freshly killed girl, the tiger was found. Nongban tried to spear the tiger but he missed his target. Then the tiger sprang upon them and bit Nongban. Khamba wounded the beast, and drove it off. Then he carried Nongban to the gallery. Then Khamba entered the forest once again and found the tiger crouching in a hollow half hidden by the forest, but in full view of the gallery of the King.[49] As the tiger jumped on Khamba, he speared it through the ravening jaws, so that it died as it fell.[50]

Tiger of Goddess Panthoibi

Tortoises and turtles in Meitei culture

Tortoise/Turtle in the story of Sandrembi and Chaisra

In the Meitei folktale of Sandrembi and Chaisra, Sandrembi's mother transformed herself into a tortoise/turtle, after some time, she was killed by Sandrembi's stepmother, who was her cowife and rival. Upon being instructed in Sandrembi's dream, Sandrembi took the tortoise from the lake and kept it inside a pitcher for five consecutive days without any break. It was told to her that her mother could re-assume her human form from the tortoise form only if kept inside a pitcher for five consecutive days without any disturbance. However, before the completion of the five days, Chaisra discovered the tortoise and so, she insisted her mother to force Sandrembi to cook the tortoise meat for her. Poor Sandrembi was forced to boil her own mother in the tortoise form. Sandrembi tried to take away the fuel stick on hearing the tortoise mother's crying words of pain from the boiling pan/pot but she was forced to put the fuel in by her stepmother. Like this, Sandrembi could not save her tortoise mother from being killed.[51]

Notes

- In Meitei language, there is no difference between "sa" and "sha".

References

- "State Animal Sangai". 2014-02-01. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

Sangai is a glittering gem in the rich cultural heritage of Kangleipak (Manipur). It is said that a legendary hero Kadeng Thangjahanba of Moirang once captured a gravid Sangai from Torbung Lamjao for a loving gift to his beloved Tonu Laijinglembi. But as ill luck would have it, he found his beloved to be at the palace of the king as his spouse and, as such, all his hopes were shattered. In desperation, the hero released the deer free in the wild of Keibul Lamjao and from that time onwards the place became the home of Sangai.

- Khaute, Lallian Mang (2010). The Sangai: The Pride of Manipur. Gyan Publishing House. p. 55. ISBN 978-81-7835-772-0.

- Singh, Ch Manihar (1996). A History of Manipuri Literature (in English and Manipuri). Sahitya Akademi. p. 201. ISBN 978-81-260-0086-9.

- T.C. Hodson (1908). The Meitheis. London: David Nutt. p. 146.

- T.C. Hodson (1908). The Meitheis. London: David Nutt. p. 147.

- Chakravarti, Sudeep (2022-01-06). The Eastern Gate: War and Peace in Nagaland, Manipur and India's Far East. Simon and Schuster. p. 254. ISBN 978-93-92099-26-7.

- Session, North East India History Association (1990). Proceedings of North East India History Association. Original from:the University of Michigan. The Association. pp. 133, 134.

- Bhattacharyya, Rituparna (2022-07-29). Northeast India Through the Ages: A Transdisciplinary Perspective on Prehistory, History, and Oral History. Taylor & Francis. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-000-62390-1.

- Singh, N. Joykumar (2002). Colonialism to Democracy: A History of Manipur, 1819-1972. Original from : the University of Michigan. Spectrum Publications. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-87502-44-9.

The construction of ' Kangla Sa ' (Lion like animal) at the front of the gate of Kangla was a great achievement of his beautification programme.

- Lipoński, Wojciech (2003). World sports encyclopedia. Internet Archive. St. Paul, MN : MBI. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-7603-1682-5.

- Neelabi, sairem (2006). Laiyingthou Lairemmasinggee Waree Seengbul [A collection of Stories of Meetei Gods and Goddesses] (in Manipuri). Longjam Arun For G.M.Publication, Imphal. pp. 156, 157, 158, 159, 160.

- Internationales Asienforum: International Quarterly for Asian Studies (in English and German). Weltform Verlag. 1989. p. 300.

Lainingthou Nongsaba ( Lion , King of the Gods )

- Singh, Moirangthem Kirti (1993). Folk Culture of Manipur. Manas Publications. ISBN 9788170490630.

- Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (1901). Man. London. p. 85.

- Man. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 1913. pp. 10, 81, 85.

Nongshāba . — The head Maiba of Moirang informed me that when the universe was in the making and all was dark this powerful " Lai " produced light . Nongshāba may mean maker of the sun . 2 Lai - sang.- This is a prosaic looking building ...

- Leach, Marjorie (1992). Guide to the gods. Gale Research. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-873477-85-4.

- Leach, Marjorie (1992). Guide to the gods. Gale Research. p. 362. ISBN 978-1-873477-85-4.

- Singh, N. Joykumar (2006). Ethnic Relations Among the People of North-East India. Centre for Manipur Studies, Manipur University and Akansha Publishing House. pp. 47, 48. ISBN 978-81-8370-081-8.

Not only this, the deity of Lord Nongshaba was also worshipped by both communities. To the Moirangs, Nongshaba was worshipped as lineage deity and regarded as the father of Lord Thangjing.

- General, India Office of the Registrar (1962). Census of India, 1961. Manager of Publications. p. 53.

Nongshaba and his wife Sarunglaima come in person, two by no means beautiful figures. The reason of this is that they are the parents of the Thangjing. Nongshaba is the greatest of the umang - lai or forest gods.

- Parratt, Saroj Nalini (1980). The Religion of Manipur: Beliefs, Rituals, and Historical Development. Firma KLM. pp. 15, 118, 125. ISBN 978-0-8364-0594-1.

There are two references also to Nongshāba, who, as we have seen, was the father of the Moirāng god Thāngjing.

- Anthropos (in English, French, German, and Italian). Zaunrith'sche Buch-, Kunst- und Steindruckerei. 1913. p. 888.

Ses parents sont Nongshaba et son épouse Sarumglaima . Le premier est le plus grand des Umanglai ou dieux de la forêt ; il produisit un fils unique , Thangjing , le dieu suprême de Moirang . La manifestation de Thangjing constitue le ...

- Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (1901). Man. London. p. 81.

- Parratt, Saroj Nalini (1980). Religion Of Manipur. Firma Klm. p. 15.

- S Sanatombi (2014). মণিপুরী ফুংগাৱারী (in Manipuri). p. 51.

- Tamang, Jyoti Prakash (2020-03-02). Ethnic Fermented Foods and Beverages of India: Science History and Culture. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-981-15-1486-9.

- Meitei, Sanjenbam Yaiphaba; Chaudhuri, Sarit K.; Arunkumar, M. C. (2020-11-25). The Cultural Heritage of Manipur. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-29637-2.

- B. Jayantakumar Sharma; Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh (2014). Folktales of Manipur. p. 51.

- Oinam, James (2016-05-26). New Folktales of Manipur. Notion Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-945400-70-4.

- Oinam, James (2016-05-26). New Folktales of Manipur. Notion Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-945400-70-4.

- B. Jayantakumar Sharma; Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh (2014). Folktales of Manipur. p. 52.

- Oinam, James (2016-05-26). New Folktales of Manipur. Notion Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-945400-70-4.

- B. Jayantakumar Sharma; Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh (2014). Folktales of Manipur. p. 53.

- Oinam, James (2016-05-26). New Folktales of Manipur. Notion Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-945400-70-4.

- Oinam, James (2016-05-26). New Folktales of Manipur. Notion Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-945400-70-4.

- B. Jayantakumar Sharma; Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh (2014). Folktales of Manipur. p. 54.

- Oinam, James (2016-05-26). New Folktales of Manipur. Notion Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-945400-70-4.

- Oinam, James (2016-05-26). New Folktales of Manipur. Notion Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-945400-70-4.

- B. Jayantakumar Sharma; Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh (2014). Folktales of Manipur. p. 55.

- Oinam, James (2016-05-26). New Folktales of Manipur. Notion Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-945400-70-4.

- Verma, Shalini (2017). Common Errors in English. S. Chand Publishing. ISBN 978-93-85676-20-8.

- Culture, India Department of (2002). Annual Report. Department of Culture.

- "Story of a Giant Poubi lai". The Pioneer.

- "Manipur's Loch Ness monster and other folktales at Wari-Jalsa storytelling fest". The Week.

- –Tal Taret (in Manipuri). 2006. p. 39.

–Tal Taret (in Manipuri). 2006. p. 48.

–Manipuri Phungawari (in Manipuri). 2014. p. 203.

–Regunathan, Sudhamahi (2005). Folk Tales of the North-East. Children's Book Trust. ISBN 978-81-7011-967-8.

–Singh, Moirangthem Kirti (1993). Folk Culture of Manipur. Manas Publications. ISBN 978-81-7049-063-0.

–Eben Mayogee Leipareng (in Manipuri). 1995. p. 107. - S Sanatombi (2014). মণিপুরী ফুংগাৱারী (in Manipuri). p. 57.

- –Regunathan, Sudhamahi (2005). Folk Tales of the North-East. Children's Book Trust. ISBN 978-81-7011-967-8. Archived from the original on 2022-06-13. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

–Singh, Moirangthem Kirti (1993). Folk Culture of Manipur. Manas Publications. ISBN 978-81-7049-063-0. Archived from the original on 2022-06-13. Retrieved 2022-06-13. - Devy, G. N.; Davis, Geoffrey V.; Chakravarty, K. K. (2015-08-12). Knowing Differently: The Challenge of the Indigenous. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-32569-7. Archived from the original on 2022-06-13. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- –Sangeet Natak. 1985. Archived from the original on 2022-06-13. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

–Krasner, David (2008). Theatre in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-4043-0. Archived from the original on 2022-06-13. Retrieved 2022-06-13. - T.C. Hodson (1908). The Meitheis. London: David Nutt. p. 150.

- T.C. Hodson (1908). The Meitheis. London: David Nutt. p. 151.

- Beck, Brenda E. F.; Claus, Peter J.; Goswami, Praphulladatta; Handoo, Jawaharlal (1999). Folktales of India. University of Chicago Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-226-04083-7.