Anders Dahl

Anders (or Andreas) Dahl (17 March[1] 1751 – 25 May 1789) was a Swedish botanist and student of Carl Linnaeus. The dahlia flower is named after him.[2]

Anders Dahl | |

|---|---|

| Born | 17 March 1751[1] Varnhem, Västergötland, Sweden |

| Died | 25 May 1789 (aged 38) Åbo (now Turku), Sweden–Finland |

| Other names | Andreas Dahl |

| Education | Uppsala University |

| Known for | Observationes botanicae circa systema vegetabilium divi a Linne Gottingae 1784 editum, quibus accedit justae in manes Linneanos pietatis specimen |

| Parent(s) | Christoffer Dahl and Johanna Helena Enegren |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany |

| Institutions | Royal Academy of Åbo |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Dahl |

Early life and education

Andreas (Anders) Dahl was the son of Christoffer Dahl, a preacher, and his wife, Johanna Helena Enegren. He was probably christened "Andreas" but was known as "Anders". He had an older brother Erik who was born in 1749, also in Varnhem.[3]

In 1755, the family moved from Varnhem to the parish of Saleby outside Lidköping where his father became the parish priest; Anders' younger brother Kristoffer was born there in 1758. His mother died in 1760, and two years later, Christoffer married Helena Elisabeth Kolmodin, daughter of the poet Olof Kolmodin. A half-brother, Olof Kolmodin Dahl, was born in 1766. After his stepmother's death in 1768, his father married for a third time; Anna Christina Svinhufvud, in 1770. Christoffer Dahl died a year later, in 1771.[3]

From an early age Dahl was interested in botany. Anders Tidström, a disciple of pioneering botanist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus, met the nine-year-old Dahl during his second journey through Västergötland in 1760, and mentions in his travel diary both young Anders' interest in botany, and his collection of plants (received from his uncle Anders Silvius, a chemist in Skara).[4]

In 1761 Dahl began school in Skara, and found several schoolmates who shared his interest in natural science. In conjunction with the parish priest and naturalist Clas Bjerkander, Dahl, Johan Abraham, entomologist Leonard Gyllenhaal,[5] chemist Johan Afzelius, Daniel Næzén and Olof Knös founded "The Swedish Topographic Society in Skara" on 13 December 1769. The members reported on plant and animal life, geography, topography, historical monuments and economic life, mostly in the Västergötland area. During this time Dahl wrote several essays in these subjects; most of them are still unpublished.

On 3 April 1770 Dahl entered Uppsala University, where he became one of Linnaeus's students. After his father's death in 1771, Dahl's family fell into financial straits and he had to leave school; prematurely ending his formal education. On 1 May 1776 he passed a preliminary candidate exam for medicine, the equivalent of a bachelor's degree.

Life as a naturalist

On a recommendation from Linnaeus, Dahl served as curator at the private natural museum and botanical garden of Clas Alströmer, a Linnaean disciple, at Kristinedal in Gamlestaden, outside Gothenburg. Dahl's employment involved several journeys in Sweden and abroad, where he collected natural history specimens both for Alströmer and himself. During that time, Alströmer received several plants from Linnaeus himself, and Dahl was able to review the Linnean collection, which is now included in the collections of the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm.[6]

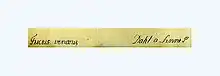

In 1781, Alströmer provided the financial backing for Linnaeus's son, Carl Linnaeus the Younger, to journey to England; on the Younger's death in 1783, Linnaeus sent Alströmer the herbarium parvum. This herbarium consisted of duplicates sorted out from Linnaeus' personal herbarium and other plants collected by his son. Dahl catalogued every specimen in the herbarium in his own handwriting, noting whether they came from "a Linné P[ater]." (father) or "a Linné f[ilius]." (son). It is clear that Dahl also received specimens; some specimens are labelled "Dahl a Linné P." or "Dahl a Linné f." On Alströmer's death in 1794, the herbarium was left to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, then to the Swedish Museum of Natural History. The specimens Dahl and Alströmer received from Linnaeus and his son are in the Linnean herbarium in Stockholm.[6]

When Alströmer experienced financial losses in 1785 and moved to his estate at Gåsevadsholm, outside Kungsbacka, Dahl followed.

In 1786, the University of Kiel conferred an honorary Doctorate of Medicine on Dahl in Kiel, Germany, and the following year he became associate professor at the Academy of Åbo in Turku (today's University of Helsinki), teaching medicine and botany. He brought his personal herbarium to Turku, which later was destroyed in the historic fire of 1827. Parts of Dahl's collections have been preserved in Sahlberg's herbarium in the Botanical Museum at the University of Helsinki, and in Giseke's herbarium in the Royal Botanical Garden at Edinburgh.

Dahl died in 1789 in Turku at the age of 38.

Publications

Dahl's inventories of flora around Skara and Saleby, and some of the papers he wrote during as a student at Skara and Uppsala are in the Olof Knös Collection in the county library of Skara.[4] The collection includes the minutes of "The Swedish Topographic Society in Skara" which contains some papers written by Dahl. Inspired by Linnaeus, Dahl wrote a Horologium Florae, a "flower-clock" of Skara, which was posthumously published in Ny Journal uti Hushållningen, in May–June 1790. Olof Knös was the keeper of the minute-book and most probably published the article. Johan Abraham Gyllenhaal's collections in the university library at Uppsala also contain some papers written by Dahl.

On 3 January 1777, an excerpt from an anonymous letter was published in Inrikes Tidningar. The writer had, during a journey from Stockholm to Gothenburg in July 1776, visited "Himmels-Källan" in Varnhem. The letter describes the quality of the spring and 58 species from the swamp around it are. It is presumed that since Dahl often visited Varnhem and his friend Jonas Odhner that the letter came from him.

Dahl's only publication during his time in Gothenburg was a result of what was probably one of the first environmental-impact studies. Waste from the manufacturing of herring oil was a major problem, causing polluted water and sea bed organism death. Dahl was one of three members of a commission who studied the issue and wrote regulations regarding waste products from the try houses. This document was the first historical step towards a restriction of industrial waste in Sweden. Dahl's diary on the draggings in the archipelago of Bohuslän was published in Stockholm's Trangrum-Acten in 1784.

During his short time at Turku Dahl published his most important work: Observationes botanicae circa systema vegetabilium divi a Linne Gottingae 1784 editum, quibus accedit justae in manes Linneanos pietatis specimen (Kopenhagen, 1787).

Dahlia eponymy

The naming of the dahlia after Dahl has long been a subject of some confusion. Many sources state that the name was bestowed by Linnaeus. However, Linnaeus died in 1778, more than eleven years before the plant was introduced into Europe, so he could not have been the one to honour his former student. It is most probable that first attempt to scientifically define the genus was done by Abbe Antonio Jose Cavanilles, Director of the Royal Gardens of Madrid, who received the first specimens from Mexico in 1791, two years after Dahl's death.[8]

Dahl was also honoured in the 1780s, Carl Peter Thunberg, a friend from Uppsala, named a species of plant from the family Hamamelidaceae after him. The Dahlia crinita is a reference to Dahl's appearance, probably to his large beard, since crinita is Latin for "longhaired". Thunberg finally published the name in 1792. The plant has now been reclassified as Trichocladus crinitus (Thunb.) Pers..[9]

Thunberg's original specimen is in the Swedish Museum of Natural History.

He was also honoured in 1994, when Constance & Breedlove, named a genus of plant from New Mexico, Dahliaphyllum after him,[10] along with its one species Dahliaphyllum almedae Constance & Breedlove.[11]

References

- In 1751, Sweden still used the Julian calendar, so the birth date might be off by 10 days.

- Stafleu, F. A.; Cowan, R. S. Cowan, Taxonomic literature, vol. 1: A-G - Utrecht, 1976.

- Mejier, B.; Westrin, Th., eds., Nordisk familjebok, konversationslexikon och realencyklopedi, femte bandet, Stockholm, 1906.

- Kilander, S., "Anders Dahl som botanist och topograf i Västergötland", Västgötalitteratur, 1988, p. 3-27.

- Franzén, Olle, "Gyllenhaal, Leonard", Svenskt biografiskt lexikon, Vol. 17, pp. 558-561.

- Lindman, C. A. M., "A Linnaean Herbarium in the Natural History Museum in Stockholm", Monandria-Tetrandia. - Arkiv för botanik, 7:(3), 1907, p. 1–57.

- International Plant Names Index. Dahl.

- Weland, Gerald, "The Alpha and Omega of Dahlias", American Dahlia Society, p.2

- Corneliuson, J., Växternas namn. Vetenskapliga växtnamns etymologi, Wahlström & Widstrand, Stockholm, 1977.

- Burkhardt, Lotte (2018). Verzeichnis eponymischer Pflanzennamen – Erweiterte Edition [Index of Eponymic Plant Names – Extended Edition] (pdf) (in German). Berlin: Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum, Freie Universität Berlin. doi:10.3372/epolist2018. ISBN 978-3-946292-26-5. S2CID 187926901. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- "Dahliaphyllum almedae Constance & Breedlove | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science". Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 16 August 2021.